Dream Role

efore we get to The Dream,

efore we get to The Dream,

we must visit the beach.

The beach is where Natalie Nakase is sweating through a Navy SEAL workout with Billy Knight and Earl Watson. The trio attended UCLA together a decade ago, playing basketball for the Bruins. Now, during an afternoon session in Santa Monica beneath the blazing summer sun, they are shuffling and backpedaling and straining on the constantly shifting sand.

A few minutes into their session, a man bikes past and eyes them, craning his neck to get a better look at the unusual scene: two strong, tall, black men crawling on the beach alongside a small, fit, Asian woman. "We always draw a few stares," Nakase says with a laugh. "I guess people don't see this every day."

Nakase has spent the past few years coaching professional basketball overseas -- coaching men who tower over her -- and the 32-year-old California native earns a living in the offseason by training kids and college players. She doesn't have to be here today, submitting to this torture with Watson, a veteran NBA point guard, and Knight, a shooting guard who plays abroad. But all three friends are chasing something, an intangible edge that comes with pushing the limits.

Which is why Nakase is dragging a 15-pound weight bag through the sand between four orange cones about 20 yards apart, pausing at each one to do 20 soldierlike pushups. After she finishes her last set, she rises, covered in sweat, chest heaving, and brushes the sand off her shins and knees. She has not rested more than a minute before Knight grabs a weight bag and takes off running for a distant lifeguard stand. The 5-foot-2 Nakase follows him, her strides short and strong. Knight returns first, then collapses into the sand and watches while Nakase grinds through her final steps. As Watson looks on, he says to Knight, "NBA players wouldn't even do this s---; they'd quit halfway through."

The day before, Nakase had told Watson her ultimate goal, the same one she had expressed to Knight a year earlier:

"I want to coach in the NBA."

She said it with conviction, strong and true, like a blow-by to the rim. She has gradually learned to do this, to own The Dream. Before, she would float the words out there -- I know it's crazy, but … I kind of think, maybe … I might want to coach in the NBA -- and the syllables seemed to deflate, falling to the ground before they reached their destination.

Nakase cares what Watson thinks -- she cares a lot -- and not just because he has spent 11 years in the NBA (currently with the Utah Jazz). Back in college, when she was a walk-on guard for the UCLA women and he was an unheralded recruit for the Bruins men, Watson inspired her to become a better player. He doesn't know this, but she cherishes the times they sat in his dorm room and talked basketball. She saw him work for his dream, late at night inside Pauley Pavilion, when no one else was around. And she wanted to work, too.

So when Watson tells Nakase, quite simply, "I would hire you," he has done more than he can understand. Those four words are like jet fuel, sending her off with renewed conviction. She attacks the beach workout as if her NBA future depends on it. And in some ways, it does.

The pushups, the sprints, the crawls, the slides -- they fortify Nakase and will help her to destroy one of the excuses NBA people will use to dismiss her. General managers and coaches won't say, "We don't hire women." They'll have other reasons and arguments, such as, "We need someone who challenges our guys." They'll have justifications, an endless supply, for upholding the status quo.

Natalie Nakase wants to be the first female coach in the NBA. And when you're trying to do something never before done, you must first understand all of the reasons you might not succeed.

It's hard to earn the respect of NBA players.�

In September, Nakase began a yearlong internship with the Los Angeles Clippers. She works for the team's video coordinator, in the same kind of NBA entry-level position once held by Miami Heat coach Erik Spoelstra, Los Angeles Lakers coach Mike Brown and Portland Trail Blazers assistant Kaleb Canales. (There has been only one woman in NBA history to work as a video coordinator: Trish McGhee, who was laid off by the Memphis Grizzlies because of the lockout of 2011.)

The job requires a continuous stream of caffeine and an inexplicable passion for X's and O's. Nakase loves it. Even though she is overqualified for the position, she feels grateful to have it -- to have pried open the NBA door and stuck her foot in the gap.

The NBA possesses more of a herdlike mentality than it cares to admit. Just look at the analytics revolution that is sweeping the league. A few teams -- the Boston Celtics, Dallas Mavericks and Oklahoma City Thunder -- had success making decisions based on new statistical formulas, and the rest are now scurrying to catch up, hiring their own numbers guys. Houston Rockets general manager Daryl Morey says all NBA teams want to be ahead of the curve, but few can afford the risk. "It's always easier when you have one example to point to, so when you take that idea to your owner, you can say, 'See, it worked here.' Nobody wants to be the first."

This mentality is one reason women aren't being hired as NBA coaches -- because no team has done it yet. The league loves to recycle, with teams routinely installing coaches and general managers who've been hired and fired multiple times. But, as Morey puts it, "I find it hard to believe that all of the best and smartest thinkers in basketball just happen to share the same chromosome."

Nakase is hoping others will see it the way Morey does. She spent last season as coach of the Saitama Broncos in Japan's top-tier men's pro league, where she was the first woman to call the shots. She took over the struggling Broncos midway through the season when the head coach stepped down and the team's owners -- having noticed Nakase was basically running the show anyway -- officially handed her the reins. (Nakase was the seventh coach in as many seasons for Saitama, a perennial cellar dweller, and she left the club in June after failing to reach an agreement with management regarding her role in player personnel.)

Jayme Miller, a 6-8 forward who played his college ball at Cal State Northridge, was one of Saitama's imports last season. Like everyone else on the Broncos, Miller had never been coached by a woman. But he says Nakase proved herself from the outset, first as an assistant and then as the boss, making her gender a nonissue. She jumped into drills to demonstrate what she wanted. She arrived early and stayed late for anyone who needed extra work. She watched film into the early-morning hours. "She came at us like a competitor," Miller says. "Because that's what she is."

Nakase's season with Saitama was her second in Japan. She spent the first as a volunteer assistant for the Tokyo Apache under the tutelage of former NBA coach Bob Hill. Nakase had gone to Japan on a whim, packing a bag and crashing with a friend from California, Darin Maki, who played for the Apache. She was initially hoping to catch on with a women's team and get back into playing, but she learned upon arrival that the Japanese women's league doesn't allow foreign players. With that door closed, Nakase asked Maki to find out whether Hill would allow her to observe practices.

The year turned into an eye-opening apprenticeship for Nakase, who eventually persuaded Hill to let her help out at practice. He, in turn, asked upper management to make her part of his staff. On road trips, Nakase would sit next to Hill, who has coached four NBA teams, and pepper him with questions about concepts and drills and language. "She is a junkie," Hill says. "She convinced me that this is what she wants to do."

Nakase had spent her entire adult life involved in the game, first as a three-year starter at UCLA, then as a player with the San Diego franchise of the now-defunct National Women's Basketball League. She tried out for the WNBA, coached for an AAU club and spent two years in Germany, playing for a season, then serving as coach of Wolfenbuettel, a pro women's team.

And yet, when Nakase stood inside that Tokyo gym, watching and listening to Hill run practice, it was like attending a symphony. Hill was using a vocabulary she had never heard before, exhorting his players with terms like "downing" (forcing the ball handler away from a screen and toward the baseline) and "X3" (bringing the small forward to double-team the post player). Although Nakase recognized the movements, the game seemed efficient and seamless in a whole new way.

Inspired, she immersed herself in the smallest details. She would work through the night on a scouting report, then passionately present her findings to the team. Nakase and Hill had an easy rapport, and, as she grew more conversant in his coaching philosophy, he happily took her under his wing. He showed her how he mapped out practices, how he broke down film of an opponent and why he likes trapping out of timeouts. Nothing was done without thought; there was a strategy behind everything, especially with the ordering of the drills on the practice schedule.

Nakase didn't sleep much that year. "There was a sincerity about the way she approached her work," Hill says. "Whatever the guys needed -- stay late to rebound? -- no problem. After what I saw from Natalie that year, I wouldn't bet against her."

Hill's mentorship continued after Nakase moved on to Saitama, with the two talking regularly. When Nakase returned to Los Angeles this past spring, she knew what she wanted to do next, and Hill encouraged her. If you want the NBA, he told her, don't take your eyes off that goal. Never turn down an invitation to step foot inside an NBA facility.

Connections matter in the NBA, just like they do anywhere else. And with his lengthy r�sum�, 64-year-old Hill is just one degree removed from every decision-maker in the league. A quick phone call or email from Hill on Nakase's behalf can go a long way toward making people pay attention. Just having him in her corner gives her huge confidence.

"He's the reason I'm chasing this dream," Nakase says of Hill. "I was so fascinated by his experiences. With him, basketball was 24/7, and I wanted to be a part of that. He opened my eyes to what basketball can be."

But Nakase's resolve was tested this summer. In July, her former coach at UCLA, Kathy Olivier, who now runs the UNLV women's program, offered Nakase a graduate assistant position on her staff. The job was a sure thing, and chasing the NBA was a long shot.

People have cautioned Nakase that her desire to coach in the NBA could rub some folks the wrong way, creating the impression that she thinks she's too good to coach women. The people who have called this to her attention are men with NBA jobs, men who have told her she should be more open to coaching on the women's side. After all, the women's game had opened a lot of doors for her, right? Did she want to come across as ungrateful, as somehow disparaging female players and coaches?

So after Olivier called to offer her a job, Nakase felt conflicted. She went back to Hill, calling him on Skype while he was in Kiev, where he was consulting with the Ukrainian national team. Hill listened, then reiterated his earlier advice: Stay the course. He knew accepting a job in the women's game would brand Nakase as a women's basketball coach, making it that much more difficult for her to cross back over to the men's side.

Nakase turned down the UNLV job and immediately felt at peace again. Inside her head, and her heart, the answer was always simple: "I want to coach in the NBA. I want to coach at the highest level."

"We want to go in a different direction."

In 1997, the NBA signed Violet Palmer and Dee Kantner as referees, making them the first female officials for any major U.S. pro sport. This was a top-down operation, the brainchild of league commissioner David Stern. The NBA, and Stern in particular, has always had a strong record with female and minority hiring. Women are present at virtually every level, from the league office to the business side to scouting. But these are hires made predominantly by suits in offices welcoming other suits to offices. The locker room, the hardwood, is still seen as sacred territory.

The topic of women coaching in the NBA has surfaced from time to time. But in years past, the only woman mentioned with any seriousness was longtime Tennessee women's coach Pat Summitt, the winningest basketball coach in NCAA history, male or female. In other words, only a woman with Summitt's credentials could be deemed capable of coaching men. At the same time, this theoretical moment -- "Female To Coach NBA Team!" -- is invariably portrayed as a splashy, front-page kind of move, a socio-cultural experiment doubling as a marketing ploy, like a scene from the movie "Eddie" with Whoopi Goldberg, who plays a super fan plucked from the rafters of Madison Square Garden and inserted as coach of the New York Knicks.

The problem with these scenarios is they never account for the possibility that a behind-the-scenes player will rise up to steal the show. The NBA's first female coach probably won't be a Big Name hired as a publicity stunt. She will, more than likely, be someone like Nakase: an obsessively determined woman willing to start on the bottom rung of the NBA ladder, no matter how many people advise her that more opportunity exists in the women's game.

Billy King, general manager of the Brooklyn Nets, says he thinks the NBA will employ a female assistant coach within the next 10 years. But, King cautions, the hire must be made by an established head coach with the full respect of his players, and the woman in question must be better than good -- as is usually the case for someone breaking down barriers. "Whenever you're the first, people don't want to see you succeed," King says. "I think there would be a lot of cruel jokes made behind closed doors, and there would be a lot of people trying to make sure it didn't work."

"NBA life is 24/7."�

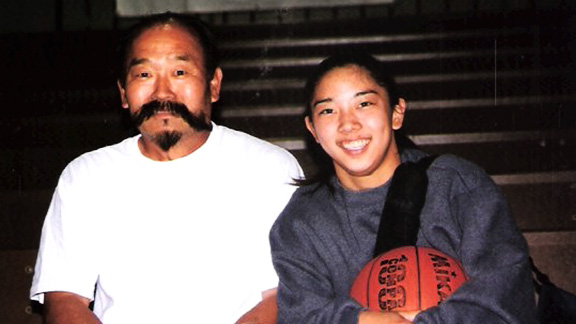

Natalie Nakase grew up in Huntington Beach, Calif., the youngest of three daughters born to Gary and Debra Nakase, both second-generation Japanese-Americans. Gary, who runs the family's plant nursery business, loved playing basketball in Orange County rec leagues. When Natalie was 10, he built a sport court in their large backyard, installing lights so the girls could play after dark. A few years later, he added a weight room in a white shed just next to the court. The Nakase girls became the envy of the neighborhood, with a steady stream of kids dropping by to play hoops, volleyball and soccer.

Natalie possessed more athletic ability than her two older sisters, and, as her basketball game continued to improve at summer camps and weekend tournaments, Gary began paying for private training on Saturday mornings. He took a traditional father-knows-best approach to raising his daughters, and wanted to instill discipline in Natalie at an age when kids are inclined to rebel against it. "I told her, 'You have potential, but you must practice,'" Gary recalls. So Natalie practiced.

"Did I like it all of the time? No, I didn't," she says. "Growing up, I felt like I couldn't have any fun, but spending the last two years in Japan has made me understand the culture and given me insight into my dad."

Although Natalie didn't always embrace Gary's strict rules, she came to understand the value in his lessons. From a young age, she realized her short stature would require her to maximize every other asset she possessed on the court, including the intense discipline and focus Gary had cultivated. Like a lot of kids, she played sports in part to please her father. In high school, though, when the decision to quit basketball or keep playing became hers alone, she began developing a true love affair with the game, a strand of hoops fever that would eventually eclipse her father's. (In her bio page for the UCLA media guide, Natalie listed Gary as the person she most admired.)

Nakase is so single-minded about basketball that if she finds a gym hosting a high-level pickup game, she'll spend the entire day watching and scribbling notes. She has driven hours within California to observe workouts, always in the hope of discovering a new drill or fresh insight. She watches NBA TV as if it's "American Idol," engrossed in anything the channel offers, from rookie league games to the reairing of classic matchups from 20 years ago. Every time her sister Nicola, who shares an apartment with Natalie in Santa Monica, turns on the TV in the morning, a basketball channel flashes on screen. "I'm always changing it to something a little more normal," says Nicola, adding that she likes basketball, too, just not as much.

Natalie says she doesn't have time for dating right now, and doesn't want anything to interfere with her focus. She is also hyperaware of how she acts around NBA men -- coaches, players, support staff -- because she knows networking in a man's profession requires a delicate balance. When she joined some San Antonio Spurs staffers for drinks during the NBA's rookie league in Las Vegas this past summer, she made sure to call it a night on the early side, careful to show she can blend in without doing anything that might raise eyebrows.

She doesn't want distractions in her personal life; she doesn't want to cause them in her professional life. "Most of my friends don't really understand me," Nakase admits. "They always ask, 'Don't you want to go out? Don't you want to do anything else?' I just say, 'Nope. I love being in the gym.'"

There are plenty of women with Nakase's obsessive dedication to the sport. Women's college basketball is full of coaches consumed by their jobs. But Nakase says she was never content in coaching women because she was torn by her expectations. When she coached the AAU team, she held the girls to nearly impossible standards, demanding the kind of focus and precision she would require of herself, and reacting poorly when the players didn't measure up. She had little patience for discussing off-court issues, and constantly had to remind herself that not everyone cared about basketball as fiercely as she did. The same thing happened in Germany, where paychecks are small.

"In each of those jobs, I wished I could focus more on just basketball," Nakase says, admitting she's a lot more interested in X's and O's than in the recruiting, mentoring and program building crucial to success in the women's college game.

In her two seasons in Japan, Nakase came to believe her approach to basketball was best suited to coaching men at the professional level. She possesses a time-is-money focus, an utter disdain for inefficiency. When she steps onto the court, she wants to squeeze improvement out of every minute. And, although the NBA is notorious for distributing fat, guaranteed contracts that can result in complacency, the bulk of the league's players still need to improve daily as a matter of job security -- the kind of high-stakes climate Nakase thrives on. "I don't have time for messing around," she says. "It's like, 'Do you want to get better or don't you?'"

On the same day Nakase worked out at the beach with Knight and Watson, she ran a morning basketball session for three women she has trained for years since coaching them in AAU ball. Two of the women, Stefanie Corgel and Daisy Feder, are still in college (Corgel plays at Cal State Monterey Bay, Feder at UC San Diego), and the third, Jenele Peterson, recently signed a contract to play in Germany. About an hour into their workout, the level of execution dropped. Someone dribbled the ball off her foot while making a move to the hoop. Another player missed a chippy. A flurry of errant shots ensued. At that point, the only thing being elevated was Nakase's blood pressure; from her vantage point, the mistakes were not the result of fatigue but rather a lack of focus. So she walked into the middle of the drill and asked the players to stop. "Take a quick break," she said. "But when you come back, be ready to respond." (They did, finishing their session with much sharper execution.)

Part of Nakase's coaching philosophy: People are capable of more than they think. She likes to create a drill that will make her athletes balk -- such as holding a full-body plank for 10 minutes when most of them have only ever done it for one minute -- then watch as they realize the power of their own minds and bodies. Jayme Miller, the forward for Nakase's Saitama Broncos, remembers a drill in which she split the players into two groups and required each side to make 10 shots in a row from a dozen spots. Miller and his teammates grumbled to themselves. "She's crazy," they said. "We're going to be here all night."

A few weeks after Nakase introduced the drill, everyone on the team was finishing shots with a consistency they had never seen. "It makes you think," Miller says. "How much had we been limiting ourselves mentally?"

"We're looking for a coach who stays ahead of the curve."

There is a hush-hush quality to NBA off-season conditioning. If a player thinks he has found something that is dramatically improving his game -- sand workouts or an unorthodox ballhandling drill -- he doesn't want anyone else to know for fear that other guys will start doing the same thing and his edge will be lost. Dozens of NBA players train during the summer in Los Angeles, and everyone wants to know what everyone else is doing. Who's working hard, and who's coasting? Which personal trainers are devising new forms of basketball magic? Guys tell stories about Kobe Bryant sneaking into the gym before the sun rises, but nobody knows what he does in there. Goran Dragic, who signed a $34 million deal with the Phoenix Suns in July, is said to be a beast in the summer.

So when Nakase and Knight met up in L.A. in the summer of 2011, they began revamping their workouts, borrowing new drills and ideas from the city's basketball elite. Nakase became a sponge. She would hang around local gyms, taking notes, asking permission to use a drill she found particularly interesting. Eventually, she found herself watching a workout with Tyrell Jamerson, who trains Oklahoma City stars Kevin Durant and James Harden. Jamerson told Nakase she could use any of his methods, so she pieced together a new collection of drills, creating some of her own and adding a few twists.

What Nakase brings is no small addition. She understands the purpose of each drill. She can also pinpoint and correct even the most minor of technical flaws. With each movement, she processes how the shooting motion should look: feet shoulder width apart, knees over toes, hips in line, elbow to hip, ball in pocket, extend smoothly, flick the wrist downward. If any of this is inconsistent from one shot to the next, Nakase's brain signals a red flag. "Your right foot was pointed inward on that one," she might say after a miss.

No one is more appreciative of her feedback than Knight, who has spent his entire pro career overseas (currently in Japan), trying to change old perceptions. He thought he could shoot his way into the NBA after college, but once the league churns out a scouting report on a guy, it might as well be a primer for his epitaph. Here Lies Billy Knight: Couldn't Handle or Defend.

Knight is actually enjoying a renaissance in his game thanks in no small part to Nakase, who challenges him to stay low every minute he's on the court. A partnership exists between the two, forged in the past few summers, an unspoken agreement to always push each other for maximum results.

"When I say I work out with a girl, guys sort of look at me weird," Knight says. "But then they see how Natalie works and interacts with players and they want to work with her, too."

"We need someone who knows our system."�

Knight, who counts many NBA players as friends, is confident Nakase will get her chance to coach in the league. He is also quite sure a lot of guys won't take her seriously at first -- "because they're like that with all coaches," he says. Eventually, though, "once she passes all of their tests, they'll see she's really just a basketball person, and they'll respect her."

Denver Nuggets forward Andre Iguodala, who has been in the league since 2004, offers a similar take. "If a female coach knows the game, veteran players would respond well," he says. "All we want is someone who knows the game."

And that's exactly what Nakase had to prove to the Clippers.

At the beginning of September, Nakase attended a coaching clinic at the team's practice site. She almost didn't go, thinking it sounded too basic for someone with her experience. But Bob Hill was in her head again. Never turn down an invitation to step foot inside an NBA facility. So Nakase went to the clinic, convincing herself that good things happen when you least expect it.

The clinic was pretty much Coaching 101. The man running it, however, was Dave Severns, the Clippers' director of player personnel. He quickly noticed Nakase's aptitude and made her his partner in demonstrating drills. She, in turn, chatted him up during every break in the action. By night's end, Nakase had Severns' email address and an open invitation to drop him a line.

In years past, Nakase might have waited a few days to reach out to someone like Severns, being careful not to seem too eager. But when she got home from the clinic, she sent him a note and boldly requested to watch Clippers star Blake Griffin work out the next day. Severns responded immediately: Come on over.

Nakase showed up early and took scrupulous notes. When Severns introduced her to Raman Sposato, the team's video coordinator, Sposato asked her what she was hoping to do in the NBA. Seeing a sliver of an opening, Nakase darted through. "Actually," she said, "I want to do what you're doing." (Hill had long counseled Nakase that she likely would have to start as a video intern to prove herself and learn the league from the inside out.)

Sposato invited Nakase back to his office, and, the next couple of days, she was vetted as a potential intern. "The moment she walked in the door, she just wanted to learn," Severns says. "We would have conversations about X's and O's, and she would pick our brains."

Everything seemed to be going great. Severns and the video guys were ready to give Nakase the gig. There was just one obstacle, a big obstacle: Coach Vinny Del Negro wasn't on board yet.

Del Negro didn't know a thing about Nakase. Who was she? Where had she come from? How serious was she about the game? Del Negro played for Hill in San Antonio, which helped, but he wanted more firsthand proof that Nakase knew her stuff.

Instead of getting the job, Nakase was given an open invitation to observe the Clippers' summer workouts. She did, arriving early and leaving late. She settled into a corner of the gym and filled pages in her notebook: assessing each player's footwork, diagramming the angles the coaches taught, counting the number of repetitions required before moving on. Nakase's scribbling included words, phrases, numbers and arrows, like a cross between an NFL playbook and graduate-level lecture notes.

After a few days, Del Negro walked over to Nakase, intrigued to discover just what, exactly, she had been so thoroughly detailing. He asked whether he could see her notes. She handed them over. Del Negro looked down, absorbing it all for a few moments. Then he looked at Nakase.

"You've got the job," he said.