What happened to Salvador Cabanas?

He was a superstar for Club America in Liga MX, scoring nearly 100 goals. He was linked to Manchester United and was ready to lead Paraguay at the 2010 World Cup. Then he was shot in the head.

This is an ESPN FC feature. This story is also available in Spanish and Portuguese.

Salvador Cabañas is taking it easy. He's sitting back, playing a card game in his parents' backyard in Itaugua, Paraguay, dressed in the blue-and-white colors of Aquidaban. Players from the local league's second-division team, which Cabañas helps coach, are also participating around a long table, which has been strategically placed in the back corner of the yard under the shade of mango, guayaba and grapefruit trees.

Cabañas' niece and Aquidaban's self-proclaimed No. 1 fan is having her face painted, and the smell of meat cooking on the barbecue fills the air. Jokes fly around in Guarani, the local dialect, and there's some small-scale betting going on. Later, Aquidaban will play a vital promotion game in a bid to reach Itaugua's first division.

The scene isn't altogether out of the ordinary, nor is it unusual that a former international star striker like Cabañas is helping to coach a team from his neighborhood -- except for the fact that Cabañas shouldn't really be here.

On Sunday, Jan. 24, 2010, Cabañas, 29 at the time, his then-wife, Maria Lorgia, and his brother-in-law, Amancio Rojas, who was in Mexico City to visit, decided to go out for the night. They picked Bar Bar, an exclusive nightclub that attracted celebrities like Madonna, Diego Maradona and Bon Jovi, among others. Whiskey was the drink of choice, and the evening was proceeding as expected, until Cabañas went upstairs to the bathroom.

There, in the early hours of Jan. 25, an argument broke out between Cabañas and narco Jose Jorge Balderas. As tempers rose, Balderas pulled out a black pistol and, according to a witness, followed through on Cabañas' provocation to pull the trigger, and shot him in the head. The single shot, from close range, flattened Cabañas, and the .38 caliber copper-colored bullet remains wedged inside the left lobe of his brain, toward the back of his skull.

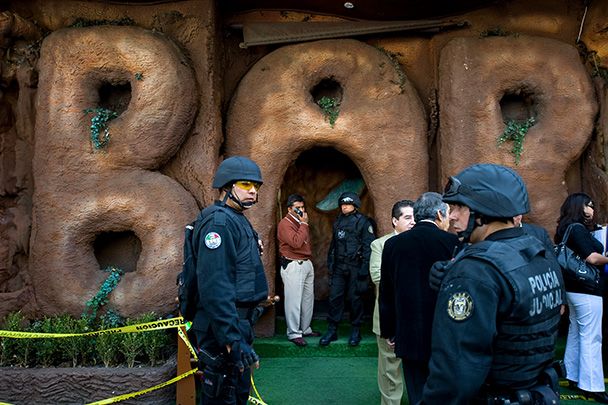

The exterior of Bar Bar, where Cabañas was shot in January 2010. Ronaldo Schemidt/AFP/Getty Images

At the time, Cabañas was a national hero in Paraguay and Club America's star striker in Mexico's first division. He'd gone from a humble family from Paraguay's interior to find wealth, fame and success at one of the continent's biggest clubs.

"I started to play football for [local club] 12 de Octubre [in Itaugua]. Then I went to Guarani in 1999. After that, I returned to 12 de Octubre. Then I was transferred to Chile to Audax Italiano, and from there I went to Mexico with Jaguares de Chiapas, and then America," said Cabañas, who averaged over a goal per game during his club career.

The shooting ended all of that, turning Cabañas' life inside-out and, ultimately, back to the shelter of his parents' home. In Paraguay, the fallout has been an ongoing and twisting saga, with questions about what happened to his finances and a trail of accusations dogging those around him.

Money was rolling in to the tune of $2.5 million per year at America at the time of the shooting, and the next step was apparently imminent: a pre-contract had been signed with Manchester United for the following summer, at least according to Rojas. Weeks later, in April 2010, Manchester United announced the signing of Javier Hernandez from Chivas de Guadalajara, America's bitter rival.

Cabañas was also set to be the central piece of the jigsaw for then-Paraguay manager Gerardo "Tata" Martino at the World Cup, and while La Albirroja reached a historic quarterfinal in South Africa, there's still a lingering sense of what could have happened had Cabañas been there.

"Tata used to say, 'I put together the team and slot Salvador in as the final piece,'" said Justo Villar, Paraguay captain in 2010 and current national-team sporting director. "You never know what would have happened in the World Cup because we were strong, but he was an important factor that we missed."

"I was on the brink of leaving for Europe, when suddenly [you had] what happened with the accident," Cabañas explained. "Everything regarding moving to Europe ended, but the most interesting thing is that we are healthy."

After finishing up the card game, and with the barbecue still being digested, Cabañas gives a short team talk and tells the Aquidaban players to not get weighed down by the pressure of the vital promotion series.

Ten minutes later, the players set off down Itaugua's backroads to play a series they would go on to lose.

For Cabañas' father, Dionisio, the relatively low quality of the game and regret about where his son could be if the shooting hadn't happened is not important right now: The fact Salvador is alive, living with him and wanting to be involved in football, brings satisfaction.

"He's better now that he's well," Dionisio Cabañas said. "Salvador's goal now is to work. He wants to work, as an assistant or coach."

Salvador Cabañas outside his family home in Itaugua, Paraguay, with Guillermo Yegros, part of the Aquidaban coaching staff. Maria Amasanti for ESPN

Scars of roughly 2 inches on each side of Cabañas' head cut vertically down over his temples, offering a permanent and visible reminder of what he's been through; the flashy earrings and three rings on his fingers are a remnant of his days as a continental celebrity. Cabañas was a player with attitude, on and off the pitch. There was an arrogance and swagger about him. Home fans loved him; opposition fans not so much. He netted 61 goals in 103 league appearances for Club America and led Paraguay to a surprising third-place finish in the notoriously difficult South American World Cup qualifying, scoring six times as Paraguay qualified for its fourth consecutive World Cup.

Cabañas still walks with his chest puffed out and his head held high. The thick footballer's calves are still prominent, but interaction with the former striker is far from fluid. While Cabañas communicates in full sentences, he repeats phrases and appears submissive in social settings, unable to give clear answers on, for example, what the exact plan is for the afternoon. All communication in terms of setting up times and places to meet is done through Rojas.

Cabañas has, however, come a long way from that night in 2010.

Cabañas, right, in action for Club America. He scored 96 goals in 115 appearances for the Liga MX giants. AP Photo/ Claudio Cruz

Cabañas was rushed in a conscious state from the bathroom floor of Bar Bar to Hospital Angeles Pedregal, a 15-minute drive. Cabañas repeated, "We're going to get through this" during the journey in the ambulance to the hospital, according to Lorgia. On arrival, Cabañas was put into an induced coma. Moving the bullet from Cabañas' brain was ruled out as early as the day after the shooting, by neurosurgeon Ernesto Martinez Duhart.

Supporters across Paraguay prayed. Club America fans set up a vigil outside the hospital. The doctors carried out emergency surgery that lasted seven hours. Cabañas' parents flew to Mexico City to be by his side as the world waited for news.

"I couldn't believe it," said Villar, who was playing in Spain at the time. "It was the shock of coming to terms with whether it was a joke, whether it was real, if he was alive, or conscious."

Cabañas responded well. He left the hospital 37 days after the shooting and was transported to a rehabilitation clinic in Mexico City, before traveling to Buenos Aires, Argentina, on March 21 for further cognitive therapy. He set foot in Paraguay again on May 22, 2010, and vowed to return to the field.

"There are obviously consequences really anytime someone suffers a head injury, but particularly a penetrative injury like a gunshot," explained Dr. Ramon Diaz-Arrastia, professor and the director of clinical traumatic brain injury research at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine.

There can also be problems with mood swings, decision-making and general organization, although Diaz-Arrastia stresses that it depends on the individual case.

"Some people refer to these injuries as 'hidden injuries,' because if you were to look at the individual, on the surface -- say you meet them at a cocktail party -- they'd look perfectly normal, but the problems they are having are in the areas of executive functioning, in the areas of mood and emotional lability," said Diaz-Arrastia, who adds that post-traumatic epilepsy and dementia are potential issues later in life for people living with bullets in their heads.

Cabañas' trophies and accolades are still prominently displayed at the crowded family home. His trophy for being top scorer in the 2007 Copa Libertadores, left, is among the clutter. Maria Amasanti for ESPN

In the immediate surroundings of the rural home Cabañas came back to in Itaugua -- around an hour's drive from Paraguay's capital, Asuncion -- there's little to connect Cabañas to the player who was named 2007 South American Footballer of the Year. Inside the house where he grew up and currently lives, however, it's a different story.

It's normal in any family home for proud parents to parade cups and trophies that their kids have won. In the Cabañas household, the trophy the striker won for topping the Copa Libertadores scoring table in 2007 sits on top of the TV stand; others to win that particular piece of silverware include Pele, Zico and Neymar. Another one of Cabañas' trophies sits on the other side of the stand, partly covered up by a Minions figurine.

On the walls of the rustic living room are paintings and photos from Cabañas' playing days and a 19th-century-style military jacket. It's the same one Cabañas wore to film a pre-2010 World Cup commercial, which portrayed him as "El Mariscal" (Field Marshal) Francisco Solano Lopez, a president painted as a heroic general in Paraguay for his role in the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870), in which Paraguayan forces fought against neighbors Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay.

The fact that Cabañas was chosen to wear the jacket provides a permanent reminder for the whole family and visitors about Cabañas' status as the country's most prominent player before the shooting.

"Greatness is not allowing yourself to be defeated by anything," reads a framed poster, presented to Cabañas by Club America, on the wall next to the jacket.

Dionisio Cabañas, Salvador's father, sits in front of the bakery they had set up years prior to help with their family finances. Maria Amasanti for ESPN

"Salvador Cabañas: Shot in the head, broke and in the bakery," read the headline of a BBC story in 2014. Even when the ninth anniversary of the shooting came around earlier this year, various media outlets resurfaced the bakery story. Cabañas and the family deny he was actually working there to make ends meet. Instead, they say Cabañas informally helped his father deliver bread and pastries around Itaugua until a couple of years ago.

The large bakery next to the family's house -- built thanks to Cabañas' income -- is no longer in use, although the smell of dough persists years later. The accessibility provided by large supermarkets over recent years has made the traditional deliveries redundant, according to Cabañas' father.

There are certainly few signs of luxury as you drive up the dirt road to the house, which is not much bigger or grandiose than those surrounding it. Cabañas, his parents and his brother (who works in construction) live in the house, as do Cabañas' sister; her husband, Rojas; and their daughter.

Accusations about what happened to Cabañas' soccer fortune have been widespread in the years since the shooting. From splitting up with Lorgia shortly after the shooting, the fallout with former agent Jose Maria Gonzalez, the struggle to get money from Club America, problems with Mexico's tax authorities and a wave of other rumors, the shooting has opened more wounds than the bullet itself.

Cabañas' ex-wife Lorgia has accused Cabañas' immediate family of manipulating him; one journalist has suggested Cabañas' family denies him medication that aids his decision-making in order to control him, and also claimed to have evidence of the family portraying Salvador's survival from the shooting as divine intervention, inviting people to donate money to pray at a shrine inside the house. The family has rejected all the claims as being false.

Lorgia has also stated that Cabañas had affairs while they were together, and Cabañas accused her of stealing from him, although last September they were pictured together at their daughter's birthday party. Lorgia made headlines herself when she took to working in currency exchange on the streets of Asuncion in 2016, claiming she needed to do so to get by.

"The family is now poorer," said Dionisio, who is amiable and open but laments the perceived lack of support from Cabañas' former teammates. "[Salvador] was our support, and economically we've gone downhill. It happened, and that's it."

Cabañas plays infrequent friendly games, for money, but hasn't traveled outside the country for some time. His story has slipped out of the Paraguayan news cycle, with a new generation of players coming through and hoping to emulate the successes of the 2010 group.

In Itaugua, the 12 de Octubre stadium offers a reminder of Cabañas' humble origins as a player. But it's noticeable that there is no stand named after the institution's greatest player and local hero; the 10,000-person capacity Estadio Luis Alberto Salinas Tanasio hasn't been renamed in his honor, and he doesn't help coach the local kids. Instead, workers there have been instructed not to talk about Cabañas to journalists, with mentions of a fallout after his awkward attempt to return after the shooting.

Amancio Rojas, the brother-in-law of Salvador Cabañas and his acting manager, waits in the stadium seats and watches as Cabanas, in the foreground, coaches at Deportivo Capiata. Maria Amasanti for ESPN

Cabañas' brother-in-law Rojas might describe himself as "a friend that helps him out more than an agent," but it is clear the husband of Cabañas' sister, Mabel, is in control of the family's situation and serves as the gatekeeper for anything to do with Cabañas. He has the full trust of Cabañas' parents, Dionisio and Basilia. Rojas accompanies Cabañas almost everywhere, and Cabañas seeks his permission to give interviews. Getting into direct contact with Cabañas is nearly impossible without going directly to the house, because he doesn't even have a cellphone.

"Everything is fine, good," Rojas said of the situation with Lorgia. "All sorted."

Rojas is also adamant that Cabañas is financially stable, pointing out that he owns a sporting complex close to Asuncion and that there is more access to money than there appears upon visiting the house.

"He earned a lot of money, thanks to God, and he has it saved up," Rojas said, without wanting to go into details.

Cabañas has the names of his children, Santiago and Mia Ivonne, tattooed on his forearms, and Rojas says Cabañas sees them regularly. Rojas adds that 17-year-old Santiago is a talented midfielder.

He's also keen to suggest that Cabañas could be set for big things as a head coach. "Ten years are a lot," Rojas said when asked where he sees Cabañas' future. "In two years or one year, I see him managing in Mexico City or a team in Mexico." There's talk of taking coaching badges, of a return to Mexico and even of the Paraguayan national team.

"I dream about a lot of things, and hopefully, at some point, I can become a head coach, become a great coach, and why not make the [Paraguayan] national team," Cabañas said. "That's what I most want."

The former Audax Italiano and Chiapas striker has an idea of how he wants his teams to play.

"I like attacking football and having a lot of the ball, which is the most interesting," he said. "I think that my players should have the ball. That's what I'm looking for when I am a coach, and hopefully it'll be soon."

Outside of his informal work with Aquidaban, Cabañas was working at Deportivo Capiata, a first-division club just 20 minutes from his house in Itaugua. Inside the dugout in Estadio Licenciado Erico Galeano Segovia, Cabañas laughed with the Paraguayan first-division club's forward, Dionisio Perez.

"I'm happy to be here with these famous players," Cabañas said with a chuckle after the first question about his role at the club. "One day, I want them to make me famous!"

This is Cabañas in his element. Engaging in dressing-room banter, speaking Guarani infused with the occasional word of Spanish, being close to the game that took him to such heights and enjoying the respect of the players. Yet his relationship with the sport is strained: He said during one of our interviews that he watches games on television, but commented three days later back at his house that watching football makes him itch to be back on the field and that he avoids it.

Even as former club America prepare to face their Superclasico rivals Chivas on Saturday night, it's unlikely Cabañas will tune in: "I watch very little Mexican football, almost none."

Cabañas, left, watches a practice game during a Deportivo Capiata training session. He admits he doesn't watch as much soccer these days because it only makes him wish he could keep playing. Maria Amasanti for ESPN

His work in Capiata began with a role overseeing the youth system in January 2017. He stepped up to become one of head coach Pablo Caballero's assistants in October 2018, until the club dismissed Caballero last December. Caballero, however, has been a key figure in trying to propel Cabañas' return to the game at a professional level.

"I met him in Mexico, where I played," said Caballero, another former Liga MX star with stints at Pumas and Puebla. "We passed each other in airports, and we had a barbecue together once. Then I came to play here [in Paraguay] in Cerro Porteño. He stayed [in Mexico] until what happened to him, and at first [after the shooting] he didn't recognize me. Then he started to remember, and now he remembers everything."

Caballero takes great pains to emphasize that Cabañas has the ability to be a coach, but he added that it has been difficult for him to find work. The money Cabañas received from his work at Capiata came from Caballero, not directly from the club, according to Caballero.

"I asked permission for him as well, because here people don't want him. We Paraguayans are incredible," said Caballero, who described Cabañas as his "idol" when he played.

Despite serving as an assistant coach, for Deportivo Capiata's first-division game against Cerro Porteño, Cabañas sat in the stands rather than being on the bench giving actual tactical instructions and advising Caballero. During training sessions, Cabañas tended to separate himself from the rest of the coaching staff. It also became clear talking to people around the club that Cabañas wasn't turning up to training every single day.

"It's up to us to try to help him, and for us to enjoy him through his anecdotes, the stories he tells and what he represents for players here in the country," said 37-year-old Capiata forward Santiago "Sasa" Salcedo, the leading career goal scorer in Paraguay's top league and Cabañas' former national-team teammate.

Salvador Cabañas poses for a photograph with a fan in Caacupe, Paraguay, as he makes his way to a holy water spring during the festivities of the Virgin of Caacupe. He's still a celebrity in Paraguay despite how his career was cruelly cut short. Maria Amasanti for ESPN

In early December, ahead of the Aquidaban team barbecue, the squad and coaching staff embarked on their pregame ritual to ask for blessings at the Basilica of Our Lady of Miracles of Caacupe, a pilgrimage hundreds of thousands of Paraguayans make each December.

The crowds swelled, even under the intense heat of the late-morning sun, and as much as Cabañas appeared to want to, there was little chance of him keeping a low profile. Hushed whispers could be heard among the crowd: "Cabañas is here. ... Is that Cabañas?" Dozens of selfies were taken as he moved down from the basilica to splash himself in the holy water of Tupasy Ykuá.

Cabañas, who used to kiss his tattoo of Jesus on his right upper arm whenever he scored, looked flustered at times with the attention but perked up as a pair of models passed by; he made a remark in Guarani in their general direction.

For former Paraguay teammate Villar, the complexities, conflicts, negative publicity and financial difficulties Cabañas has endured shouldn't be the main thing taken from his life after the shooting. The national-team sporting director sees Cabañas as an example of someone who has overcome the odds, almost in line with the national character of Paraguay's gritty history. The former goalkeeper is happy to hear Cabañas wants to work again in football and says he can use his experience to benefit young Paraguayan players.

"I think that as an example of overcoming, of struggle, of sacrifice, we can learn a lot from him, and the [national team] boys look at him and value that," Villar said. "Coming out of a humble town and being from a humble family, and to grow and achieve things.

"The fight continues for him in overcoming his problems," Villar added. "For me, he's an example that you can achieve lots of things even in the face of a lot of adversity."

"It's always difficult," Cabañas said. "It will be in every moment. Wherever you go it'll be difficult, but you have to demonstrate your value."