Football has been more than a sport for India's north-east region; it has given its people - ethnically distinct, economically neglected and culturally alienated from the national mainstream - an identity. And now, with Aizawl's stunning success in the I-League, it offers to the rest of India a lesson in how to build the sport from the grassroots.

Eight hundred and eleven. They've finally worked out the total, and it's hard to miss 811 boys. Aged 14 and below, including tykes of implausible tininess, a kaleidoscope of football jerseys, shorts and sling bags. Moving up a slope in Mualpui, a few solo, others in groups, some with mothers, sisters or aunts in tow. Heading to the stadium because some folks from Delhi have turned up.

This is Aizawl, the capital of Mizoram, so far from Delhi's centre of attention that reality becomes a wobbling mirage. The clock shows 10:30 a.m., but the sun is dead overhead, our shadows a puddle around the feet. Until you travel this far, you don't quite understand the scale of idiocy of one Indian time zone across a country that shares longitudes with both Tashkent and Lhasa, who are three time zones apart.

Boys are pouring in and out of the Rajiv Gandhi Stadium, chattering, hanging around staircases, lacing and unlacing football boots. Sons of taxi drivers, farmers, dentists, tailors, hairdressers. There is the clatter of cleats on tile, bodies slithering across artificial turf, outraged squeals and the bark of adult orders. The people from Delhi are tremulous. They belong to a second-division I-League football club called Sudeva FC and are holding trials to induct a few under-12 and under-14 boys into their development programme. Above the main stand of the stadium, Aizawl stretches across six or so hillsides. Crowded yet courteous (it's true, Mizos don't honk), busy but internally languid.

We are in the region to understand what constitutes that amorphous entity called "north-east football." Mizoram, we're told, is the place to start. Going by the past 12 hours in town, it is true. Football here is more than a sport; it is the centre of a human hurricane. Which has just hit Sudeva FC in Mualpui.

The Sudeva coaches have come off a run of pan-India trials. On a good day elsewhere, they say, between 100 and 150 aspirants show up. Aizawl's 800 leaves them benumbed. The boys are packed onto a single grandstand like spectators at a game. A third age-group has been hurriedly added because there are 6-year-olds staggering around as well. The final breakdown: 213 under-14s, 150 under-13s and 448 under-12s, total 811. "Crazy" says Vijay Hakari, one of Sudeva's co-founders. "This is crazy. We've seen nothing like it."

Indian football has never been here before either. Not to Mizoram per se, but to this point in its history where the sport's beating heart and talent base have moved from its traditional strongholds -- West Bengal, Kerala, Goa, Punjab -- into a territory rarely acknowledged or understood. It's a part of the country that is ethnically distinct, politically troubled, economically neglected and culturally alienated from the national mainstream. Where, as football journalist-commentator Novy Kapadia says, "neither Bollywood nor cricket has reached."

Football, however, has. A little over 3 percent of the country's population now provides more than 20 percent of the sport's professional footballers, including 91 of the 300 in its top division. India's squad in its most recent international -- against Myanmar on March 28 -- had three north-eastern players in its starting XI and four more on its bench. When India hosted the Asian under-16 Championships last year, the squad had nine north-easterners out of 20; seven started in a match against Iran. The first Indian Women's League, held from October of last year through February, featured three teams -- including the winners, Eastern Sporting Union of Manipur -- from the north-east out of a total of 10 in the competition.

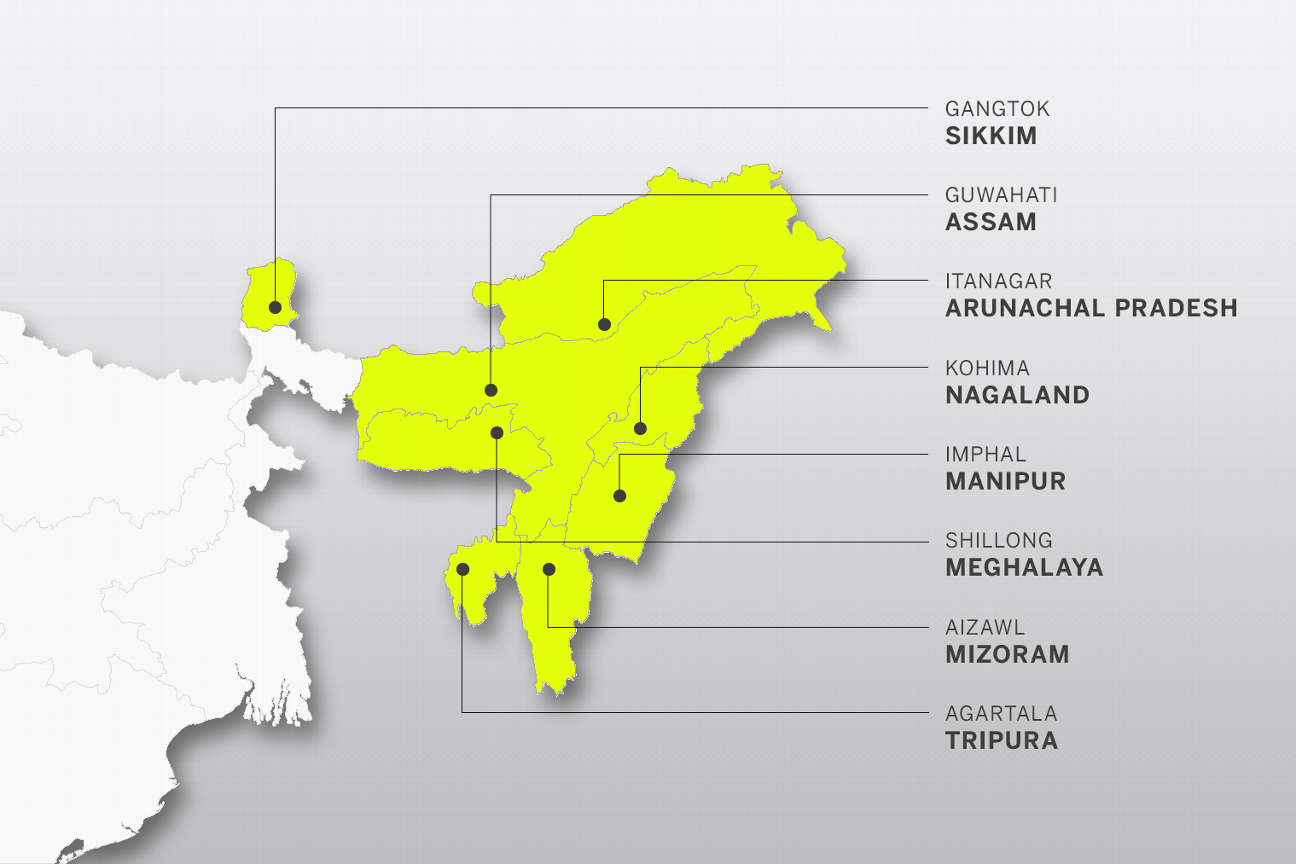

Data and history become good starting points for this adventurous project. The generic phrase "north-east" is rather broad-brush; it includes eight states and 45.8 million people. Of these, three, maybe four, states have produced a regular tranche of footballers over the past 25 years.

Sikkim, Manipur and to an extent Assam were the earliest. They were followed by Meghalaya, home to the region's first professional football club, Shillong Lajong FC. Assam is the biggest state in the region in terms of resources and population but is left behind by Manipur in player numbers and Meghalaya in structures and programmes.

Mizoram's soaring football, meanwhile, has become a model of how to enrich a culture and create an industry. Today, if Shillong Lajong is the engine for the region's growth, Royal Wahingdoh's third place I-League finish in 2015 the spark that fired it and Bhaichung Bhutia's presence and status its hood ornament, Mizoram has become the foot on the pedal, maybe even the pedal itself.

Mizoram's football has neither the history nor the hang-ups of the Kolkata clubs nor Goa's wild-west flavour. Its factual quirk -- there is no grass in Mizoram -- becomes a hook for visitors. In Mualpui, the football field is artificial turf, blades of green plastic. Of course, Mizoram has grass, the real kind. But the topography, with 21 hill ranges clustered north to south, means flat land is scarce and grass is hard to grow and easily washed away by floods and landslides.

Turning disadvantage into opportunity, the state has moved into overdrive in the past five years. "I had the trust in our talent that one day we could become a powerhouse," says Lalnghinglova "Tetea" Hmar, secretary of the Mizoram Football Association (MFA). "I didn't expect it so soon."

It has been quicksilver: the state's first artificial turf was inaugurated in 2011, India's first FIFA-AIFF Grassroots Programme was held in the state in 2012, the Mizoram Premier League (MPL) was created in 2012-13 and the state won the Santosh Trophy -- the national interstate football championships -- in 2014. A year later, Aizawl FC became the fifth club from the north-east and the first from Mizoram to qualify for the I-League -- first division. In 2002, Shylo "Mama" Malsawmtluanga became the first Mizo to participate in the country's highest professional competition, at that time called the National Football League (NFL); in the 2016-17 season, 54 Mizo players were registered in both divisions of the NFL's successor, the I-League. And then came Aizawl's fairytale season.

"Football takes away the tension. Not getting tickets, not getting to school every day, dealing with a bandh every alternate day. Football is the only way Manipuris think they can be in peace." Renedy Singh

In the mid-2000s, Tetea would ring big mainland clubs, requesting trials for his Mizo boys; today's Sudeva trial is Aizawl's eighth football trial of 2016. Despite wrestling with flu, he turns up at the evening's MPL match, rigged up in a jacket and Burberry scarf, to glad-hand the Sudeva crew. Tetea's choice of the word "powerhouse" is not an overreach. Mizoram has become the model football state for organisation, innovation and enterprise. It has turned its small size into an administrative advantage and its hurdles -- intrinsic, logistical, financial -- into the background score of a rousing athletic opera.

You have to be there to feel it. Football, what it means and its place in the north-east.

That which is united

My knowledge of the north-east is flimsy at best; until a short trip to Agartala to understand the phenomenon of the gymnast Dipa Karmakar in early 2016, I'd never been farther east in India than Kolkata. Like most Indians, my mental geography was generally lumpish, maybe even lumpen. Assam was elongated atop Bangladesh, Sikkim sort of squashed in between Nepal and Bhutan. Meghalaya was near Assam. Then there were the other mystifying, remote landlocked states on the other side of Bangladesh.

So far that, in the mind, they're blended together in a large mush of bad news: ManipurMizoramTripuraArunachal. And was not Nagaland about headhunters? Was Aizawl-Aizwal interchangeable? The Indian Meteorological Department website informed us that "Aizawl" was an "Invalid Station" ID. Of "Aizwal", it helpfully predicted, "Fog/mist in the morning and mainly clear sky later."

It wasn't very accurate: a thin afternoon drizzle peppered down on our landing in Mizoram's Lengpui Airport. A spare white cross fronted its terminal building, with the words: "Thy Kingdom Come."

We are in fact in a hidden kingdom of Indian football, with its distinct historical links to religion and a bounty on offer. Before the arrival of football in the 19th century, the hill tribes of the north-east always had indigenous forms of leisure, including variants of wrestling, archery and ball games. Once the British took control of the hill regions of Assam, both closer to the Mainland and far away in the Lushai Hills around what is now Mizoram, missionaries moved into the region with Christianity and football. The Welsh and American Baptists were the earliest arrivals in the 1830s, followed nearly half a century later by the Presbyterians and other denominations of the Anglican Church. The establishment of Christian missionary-run schools on the Victorian model meant that the easiest "alien" sport to teach converts was football. The north-east's geographical proximity to Bengal, the capital both of India (until 1911) and its football, kept the sport alive even through violent and fractious times.

Could the north-east, though, be studied as a single, clunky whole only because it was in the grip of a single sport? The region is a tumult of cultures, clans, tribes, religions, faiths, languages and ethnicities. Buddhist, Baptist, Donyi-Polo, Presbyterian, Hindu, Sanamahism, animism, ancestor worship, Tingkao Ragwang Chapriak. Meitei, Khasi, Assamese, Bodo, Ao, Kokborok, Garo, Mizo, Nagamese.

Wasn't trying to bind them together as uninformed as the blurry notion of the north-east being about tribals and political trouble and Mary Kom? Where did football fit? Under the Indian Super League's blanket NorthEast United FC slogan "eight states one united"?

"The flatlanders' perspective of the north-east in straight lines will always bypass the jagged edges of its history and undulations of culture and faith."

Traipsing through Aizawl, Guwahati, Dimapur, Kohima and Shillong, the question popped up in every conversation: What is that which is united? Once the shimmer and noise of the ISL's eight-states-one-united melted away, the question hung in the air, like the morning mist off the hills, invisible when surrounded by it but impenetrable from the outside.

Maybe our ways of seeing are completely wrong. A stray comment one evening nailed it when, while cooking a dazzling dinner, Xonxoi Barbora, associate professor at Guwahati's Tata Institute of Social Sciences, served up perspective to chew on. Outsiders look at the north-east, he said, through two dimensions on a flat surface -- the political map on paper or screen. This view makes hill country unfathomable to the eyes of plains people, for whom the shortest distance between two points is always a straight line.

Aizawl to Agartala should be 147 kilometres as the crow flies, less than Mumbai to Pune. On the road, it is a 340-kilometre journey and could take more than 10 hours. Kohima, northeast of Aizawl, is 258 kilometres away on a paper. In real life, it is 532 kilometres and 17 hours of hill driving. The flatlanders' perspective of the north-east in straight lines will always bypass the jagged edges of its history and undulations of culture and faith.

What the map does show is the undeniable fragility of the geography separating the hills people and the plains folk. It is a strip of land 25 kilometres long, less than 45 kilometres at its widest point and a little over 20 kilometres at its narrowest, with a railway line running through it to connect the two parts of the country. The Siliguri Corridor -- aka Chicken's Neck -- looks like a hungover cartographer's "morning after" map but is in fact a product of the Partition of India in 1947.

Over the past few decades, football has become the strongest connector between both sides of the Chicken's Neck -- and the source of a collective identity of the north-east. If you listen to Larsing Ming Sawyan, owner of Shillong Lajong FC, football is central to the region's understanding of itself as a collective whole. Larsing believes his club was the "first real pan-north-eastern initiative, the first football club or organisation outside of politics, that has looked at uniting the entire region."

Lajong were the first north-eastern club to compete in the country's highest football competition, the I-League. Their logo features the eight north-eastern states cradling a football. The word Lajong means "our own" in the Khasi language -- it certainly means far more than the acronym for the national ministry in charge of the region's affairs -- Ministry of DONER (Department of the North Eastern Region).

Larsing points out that the Chicken's Neck, while connecting the region to the mainland, also compacts it. He thinks of himself as a north-easterner: his father, the founder of Shillong Lajong, belongs to Meghalaya; his mother is Mizo; his wife Assamese. He speaks slowly, thoughtfully. Before independence, the region was not eight states but one large British-ruled province (Assam), two princely states (Manipur and Tripura) and many tribal republics. Largely similar races sharing a common stock of what is referred to as the Tibeto-Burman family of languages and a segment of what are classified as Austro-Asiatic languages; in the plains a significant percentage belong to the Indo-Aryan language stock, the many varied groups, he points out, then "engrained into a larger identity over time through geography and climate."

It is so apparent, but trust a local to pick out and identify larger, global strands breathing beyond the boundaries of the Indian nation state.

Robert Royte, the owner of Aizawl FC, one of five clubs from the region to play in the I-League's top division, has been on both sides -- a native Mizo familiar with the world of DONER while he worked in the state government's education department. In 2011, Royte was invited to head and then run a 27-year-old local club that had been defunct for nine years. He gave up his government job to set up his business and helped in the Aizawl FC revival. Today, after their second I-League season, they are champions of India.

Royte's office is a short hike from the Lammual Stadium in downtown Aizawl and reflects his working life. The North East Consultancy Services (NECS) operates in software design and civil construction, and his office walls are papered with plans and photographs of construction projects -- football academies, a women's prison and police headquarter colleges. Royte's office is full of football trophies and an eclectic collection of books ("Naga's Right to Self-Determination," "Supreme Court Labour Judgements" and "The Adventures of Detective Dailova"). Royte is small and square-framed. I had stalked him over telephone for months, and the direction of the interview -- towards the issue of north-eastern identity -- amuses him. "You're not talking about my youth academy," he laughs, but he speaks football and politics with conviction.

Football, he believes, is central to the "mainstreaming" of the region with the rest of the country. "The north-east is now known for its football, it is where the north-east enters the national arena and national levels in maximum numbers." Identity is another matter, he argues -- and this is where he differs from Larsing. "The feeling for Mizo identity, for Manipuri identity, Khasi identity, Naga identity is much stronger than the feeling for a common north-east ... in the context, let us say, of football," he says.

A sense of regional collective does exist beyond and above the sport. Mark Lalduhsaka, director of operations and marketing at the Mizoram Football Association (MFA), is a millennial and a sharp dresser with a sharp mind. He spent many years living and working with the mainlanders and when asked about identity beyond, he finds himself amused by the fact. "We are united by the stereotype that others put on us."

We know what he means, we've heard the words used and rarely tried to stop them: small eyes/flat nose/momo-eaters. One player called it "racial discrimination," and that is accurate. Stories told by the eccentric but gifted coach Bimal Ghosh provide clarity. Ghosh is a footballing frontiersman who signed on with Manipuris in the early 1980s for the Air India team. His players had faced opposition and abuse, and he repeats an ugly word used about them: chinimaka. Roughly translated, it means Chinese-Christian, the pet stereotypes dropped into casual conversation around his players. Appearance and religion wedded by ignorance.

In Guwahati, Barbora holds up a mirror of blinding light when he says the north-east was united by "the reality and memory of political violence." It is a truth football people and most sports folk do not wish to dwell on, but it is as much a part of the region's identity as football and food.

Land of a thousand mutinies

At the time of Indian independence, the region was, as Larsing said, many segments, separated by geography, culture and religion. Dialects changed from village to village, and the idea of government varied from colonial masters to royal diktats to clan gatherings. The British left India with the drunken drawing-up of two nations, three geographical entities, four regional chunks and one Chicken's Neck.

In the early decades of free India, there arose the desire and need on the part of the state to control, often by force, lands on the other side of the Chicken Neck. Among the people who lived there arose the desire to rise and resist. More than six decades of conflict between the Indian state -- military and paramilitary -- and locals in the form of protesters, insurgents, militants and rebels have left the region pockmarked by gruesome indignities and loss. Insurgencies, independence movements, political struggles, separatist demands for new states and border conflicts between the states themselves still surge through the north-east like river currents.

The response of the state to the people of the region has been either heavy-handed -- its imposition of the harsh and controversial Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) in several areas, for example -- or largely inattentive. There has been only one instance of the Indian Air Force (IAF) bombing Indian territory (you won't find this in any school history book). That was the bombing of Aizawl in March 1966 for two days in a row after rebels took control of military installations and laid siege to the Assam Rifles headquarters (on whose grounds, coincidentally, MPL matches are now held).

Historical estimates over the movements in India at odds with the state or with one another since independence have ranged from 30 to 120. It is not for nothing that the north-east is wryly referred to as the Land of a Thousand Mutinies. On the side of the rebels, some popular causes have been diluted into corruption, expediency and self-interest.

Nagaland is the totem for such an existence. In the commercial capital of Dimapur, we are being thrown around in a car on the main drag. It is essentially a tarred riverbed of a road, belching traffic and grey air. "Taxation," we are told, is the euphemism for Nagaland's extortion economy, run by the "underground." Every single adult involved in the economy pays his dues in some form or the other to someone or the other who gets it across to the "underground." The state is in the know. That mundane fact is a cold hand around the throat. A grotesquerie that is as much India as are the uber-arty airports, startup sassiness and record-breaking rockets.

Leaving the wild east of Dimapur behind and heading for Kohima on a quiet Sunday morning, the countryside is soaked in deceptive peace. There is very little traffic, only the rustle of leaves, the chattering of birds, red-throated, blue-breasted, and the taxi's gearbox clearing its throat. Along the Chathe River, which marks some of the border between Assam and Nagaland, photographer Madhu Kapparath voices a thought. If armed men were to step out of the forests and line up across our road, the outside world wouldn't have a clue.

How could football survive in such an environment? The sport offers relief, says former India international Potsangbam Renedy Singh, currently president of the Football Players' Association of India. An exhibition match organised by "expat" Manipuri footballers last summer to raise money for a cancer-stricken young player attracted between 15,000 and 20,000 people. "Football takes away the tension. Not getting tickets, not getting to school every day, dealing with a bandh every alternate day. Football is the only way Manipuris think they can be in peace."

The 'firesome' footballers

Between the 1952 retirement of Nagaland's Talimeren Ao, independent India's first football captain, and the arrival of the first of the region's big-name footballers, there lay nearly four decades. Much of this period was marked by uncertainty and violence from the 1950s to the end of the 70s; many of the region's young men found themselves on either side of a divide -- either working for the new nation-state in respectable and secure government jobs or on the other side as rebels/freedom fighters/insurgents.

There were stray names -- football historian Gautam Roy cites two from Sikkim, Pem Dorji and, a generation before him, midfielder Jerry Basi. However, the routes between the simmering north-east and national football, says Novy Kapadia, came together through three unrelated happenings: the launch of the Subroto Cup in 1960, the creation of the Sports Authority of India (SAI) in 1984 and the establishment of the Tata Football Academy (TFA) in 1987.

"At first, they would cry themselves to sleep in academy hostels far away from home, dreading the evenings at the TFA or SAI hostels, after football and before dinner, the solitary study time at desks in the gathering gloom. It is they who ensured that today the region fuels the I-League's two divisions."

Kapadia reckons the Subroto Cup, a national interschool football tournament, was the original funnel through which north-eastern footballing talent moved into the rest of the country. In 1978, St. Anthony's Shillong became the first north-eastern team to win the title. The event is now split into the under-14s and the under-17s, and the region's schools still feature regularly in the title rounds.

Most north-eastern players, both past and present, have the Subroto Cup on their CVs, and it is from there that many were signed by the TFA. Along with the TFA, the SAI's Special Area Games Programme (SAGP) bypassed every north-eastern state's own inadequate structures and drew junior talent into its own institutional programmes. From the TFA and the SAGP came football livelihoods and contracts with the big clubs or jobs into the lesser-paying but more secure government bodies like the railways, banks and petroleum companies. SAI entered their clubs into Delhi leagues, and the names began to come streaming through: C Akum, Kiran Khongsai, Somatai Shaiza, Gunabir Singh, Jewel Bey, Khemtang Paite and Gumpe Rime.

This is when Air India's Bimal Ghosh steps into the history of north-eastern football. As big clubs paid expensive foreign players, Ghosh -- operating on Air India's limited public-sector budget -- went east. A football player whose busted knees turned him into a young coach, Ghosh had seen the handful of Manipuri players in the Bombay leagues and admired their strength, agility and lung power. "They always wanted to do something or the other: tackle, go for the ball, win the ball and create chances. I thought, 'This is a different type of player with different muscles. Why don't we try them?'"

Ghosh travelled to Manipur in the early '90s and signed on two teenagers, Tomba Singh and Bungo Singh. "The contract money was not very big [between 10,000 and 15,000 rupees a month]," he says, "but the exposure was. The Air India budget was less than Mahindra's, who were one of the best teams in India, but we used to beat them all the time." He is now based in Nagpur and has brought two more Manipuris and three Sikkimese players into his local club, food and accommodation covered but nothing else. "They come to me, they know within two years they could become one of the best players in India. I have full confidence in me."

It is a sizeable boast, but Ghosh reels off the names of players signed up who went on to become either major India or club players: Manitobi Singh, Subhash Singh, Raju Singh, Nirmal Chhetri, Sanju Pradhan, Bikash Jairu, Khambiton Singh, Biren Meetai, Uttam Singh. So many Manipuris that at one point the Air India team would be derisively referred to as Air Manipur. "You cannot find better students," Ghosh says. "They are very quiet, but on the inside they are ..." He searches for a word and says "firesome."

"Firesome" belongs to no dictionary, but it is easily understood through the life stories of north-east footballers finding their way in the mainland. At first, they would cry themselves to sleep in academy hostels or sports camps far away from home, dreading the evenings at the TFA or SAI hostels, after football and before dinner, the solitary study time at desks in the gathering gloom. It is they who ensured that today the region fuels the I-League's two divisions.

Mama makes the breakthrough

"There was no phone, there was no STD booth. I used to speak only one minute, once in a week. Most of the time, I am staying alone. I am just thinking after this, I have to do this, I have to do that. I'm just taking my step every minute. I'm just going, going, going." says Shylo Malsawmtluanga, aka Mama, who belonged to South Vanlaiphai, more than 200 kilometres south of Aizawl. He had been signed up by the TFA, Jamshedpur, after a Subroto Cup performance.

A country boy who spoke little English, never mind Hindi, Mama had already earned the scorn of the football hipsters in Aizawl. In Jamshedpur, he didn't like the food; his palate -- used to boiled and steamed food -- was overwhelmed by oil and spices. He couldn't understand why some colleagues tried to rib him by asking him, a Christian, to join them in Hindu prayers or made fun of how he dressed. He had grown up following football by listening to a 30-minute weekly sports bulletin with his farmer father and always knew he wanted to play. When his primary school teachers asked him what he wanted to do in life, he would say, "I want to be a professional football player."

"I play to make some change for myself, for my people ... I want to encourage young players back home that by playing football we can live a good life." Khwetelhi Thopi

Mama became Mizoram's first professional player when he signed for East Bengal in 2002. When his first paycheque arrived -- Rs 1.5lakh -- he had no idea what to do with the piece of paper. It was kept in his Bible before "a friend told me this is very important." Today they have named a stand in the Lammual stadium after Mama, Mizoram football's Pied Piper.

Nagaland's Khwetelhi Thopi was neither Subroto prodigy nor SAI hostelite. Coerced by his family into academics, Thopi returned to the sport after graduation and trained with his old local team, Life Sports FC of Chizami village. "I have patience, if they practice for two hours, I practice for four ... after I started playing, I only think do or die." From local clubs and the Santosh Trophy, he reached I-League second-division Rangdajied United FC on a five-month contract in 2014. Last season Aizawl FC took him on loan from Rangdajied to play in the I-League first division.

To meet us in Shillong, Thopi travels more than 20 kilometres from Rangdajied's home base of Mawngap-Mawphlang, and for his photograph he wears Aizawl's red shirt. This is him, Nagaland's first player in the I-League first division, on the back of an ironclad whim and many prayers. He says, "I play to make some change for myself, for my people ... I want to encourage young players back home that by playing football we can live a good life." His fellow Nagas, he says, want to play football, "but we never dream high." He dreamt the do-or-die -- and is still doing.

India international Potsangbam Renedy Singh, currently president of the Football Players' Association of India, joined the TFA at age 11, his grandfather unable to bear hearing him cry at night because his parents wanted him to join the army. Renedy says, "Kiran Khongsai and others, they were the pioneers who started playing for the national team. ... I am sure in other fields the north-east faced a lot of problems, but in football we didn't. We had pioneers."

He takes another name. "And then there was Bhaichung."

Bhaichung Bhutia, nearly three years senior to Renedy, came to Indian football at the age of 16 on the basis of a Subroto Cup performance that hauled him into the East Bengal set-up and would turn him from schoolboy to superstar. He had earned an SAI scholarship to the highly respected Tashi Namgyal Academy in Sikkim before the school competition that would change his life. Bhutia recalls his first months with East Bengal. "It was not easy. One practice you do well and they say you did well, but it may be a one-off and you have to repeat it and repeat it more. ... I was 16, there was a bit of fear of not succeeding and having to return to Sikkim. At the same time, you are just excited to play for such a big club and you are ready to work hard and do anything to succeed."

Bhutia -- the first Indian to play professional football in England, for Bury FC -- has come a good distance from his roots in mofussil Sikkim and is an influential figure in Indian football. Whatever grumbling there may be about no true successor from his state, it was his skills and personality that made Bhutia the most popular north-eastern face across the rest of India. His name became instant recall for a sport and a people. Any doubt Bhutia may have faced in his early years from mainlanders has now dissipated into their faith in the north-eastern players' abilities -- and constitutions. Or, as Jeremy Wallang, a lean, relaxed Shillonger who returned from a club career in Goa to join Lajong in its early years, jokes about the legendary leg strength of the north-easterners, "These are hill people; some guys they have cows, not mere calves."

In his time with Lajong, coach Thangboi Singto has seen parents tilt towards football over the earlier security of government jobs: "When the I-League started [in 2007] and players started getting better salaries and contracts and parents saw senior players coming home, building houses and buying cars, building a life, that's when they said, 'This can be a career for my son.'"

Often many players wind up wiser beyond their years, like 22-year-old Holicharan Narzary, one of Assam's rare exports to the current national team. A forward with DSK Shivajians, Narzary had to choose between securing a place in an SAI hostel or returning home and helping his family cultivate paddy. Narzary is speaking to us in Guwahati's Taj Vivanta hotel; he is in his NorthEast United white jersey, lithe, almost regal, and eloquent. "I want to say to Assam boys like me, you must play as much as you can, you must play outside. Football is a game for everyone. If we play, it means others can also play. Keep playing, keep moving ahead, have the confidence you can play."

Maybe this is what "firesome" is -- enough burn inside to stay stoked and the composure to handle every onrushing crisis, be they a defender's boots or familial demands. Narzary's call to other young footballers from his state comes from the personal familiarity of working his way through a scarcity of opportunity to where he is today. Guwahati is also home to ISL club NorthEast United. Their motto of "Eight States, One United" is not exactly welcomed by the region's indigenous football community. Lajong, in fact, had equity in NorthEast United in 2014 before selling it the next season. Lajong owner Larsing is also AIFF vice president and speaks of NorthEast United and ISL with a biting civility. "The ISL has created an ecosystem for perhaps a very strong national league for the future. ... I look at these eight ISL clubs as being incubated for the future. Hopefully over time they will evolve and move from a franchise frame of mind to [being] real football clubs and start investing in long-term developmental programmes."

What requirements should NorthEast United fulfill to truly represent the region? "I don't really have much to say about that. I just hope that one day we will get to see a match between Lajong and NorthEast United."

Bring it on. Hold it in Lajong's home ground at the Polo Grounds in Shillong. Flatlanders against hills people in their own environment. No prisoners.

The third wave

Like the town it belongs to, Lajong has always moved to its own beat. Shillong is the north-east's beating heart of ubercool: gamblers, poets, renegades, hipsters and scholars consider its air their own, taxi drivers play Metallica and AC/DC over their speakers and teer -- archery gambling -- involves dream interpretation and no doubt blind luck.

It was Shillong Lajong, with its professionalism and corporate sponsorship, that became both catapult and catalyst in Indian football. It set the trend towards a smoother standard of management in Indian club football, and the rest of India has only followed, highlighted by the ISL's larger coffers and poshness. The Lajong club offices are in a corner of the Centre Point hotel owned by Larsing's family. There are photographs of past matches featuring standing-room-only crowds at the Polo Grounds-Nehru Stadium terraces and a mezzanine den set aside for visitors and trophies that overlooks the Guwahati-Shillong Road.

Larsing, from a wealthy business family, followed football while a student in Bangalore and realised that the stream of footballers from the north-east could become a torrent. "Our vision was to harness the talent of the entire region" and replicate the TFA model for hills people, he says. Grassroots youth talent scouting, scholarships for 14- to 15-year-olds and quality training "to develop a team that could represent the region in the Indian national league."

It has meant sinking private money into a project whose owners seem like doomed defenders, unable to nail down slippery profits. In 2009, Lajong sent out a call to arms for the region's older troops. Stalwarts from other teams, like Gumpe Rime -- who stayed on and is now head of youth development -- turned up, and sponsors, including big names like Adidas, Nokia and The Telegraph newspaper were cajoled into buying into the idea. Larsing claims that Lajong's Adidas sponsorship was the first real merchandising and jersey sponsorship done for an Indian football club. In 2012, an FDI investment by a firm called Anglian Holdings, through which the owners divested 15 percent equity, meant that the club were on to a good thing.

The earliest response to Lajong by "mainland clubs," Larsing says, was "perhaps a sense of a jolt, that suddenly these new entities have come out of a region that had been producing players for a decade or so prior but never really had a club identity. Perhaps everyone wondered whether we would be able to sustain ourselves." Lajong's first I-League season, 2009-10, was a bummer; the team were relegated only to return to the first division in 2011-12 and stay there since.

They still field among the youngest teams in the I-League; where the minimum requirement is least one under-22 player in the starting XI, Singto, the coach, says they field five or six U23s on average. Everyone in the region recognises that Lajong did more than raise the bar. It was to actually establish the bar -- of a club that was greater than the sum of its victories. An institution of learning, a centre of regional aspiration and a place of sustainable business.

Lajong has generated across the region what Jeremy Wallang -- a first-generation Lajonger -- calls a tsunami effect. "It got a lot of people thinking that if Lajong can do it, why not us?" Today more north-eastern clubs seek pan-Indian platforms. Aizawl FC are already the face of Mizo football across India but are looking wider. NEROCA (North Eastern Re-Organising Cultural Organisation) FC of Imphal, Manipur, reached the final of the 2016 Durand Cup and applied for, but missed out on, an I-League spot left vacant after the Goan clubs chose to miss the ongoing season.

Both Aizawl FC and NEROCA FC are renaissance outfits; older clubs run in an amateur era, soaked in history and sentiment but in danger of going defunct. Royte of Aizawl FC says his club means to unite the Zos (Mizos) "not only in Mizoram but across the world. ... They are spread out across the globe; we have a very big support base in Myanmar."

To keep the cause of the Mizos going, he knows, will require convincing many doubtful non-Mizos. "Corporates should recognise that the operational area of Aizawl FC is large, it is at par with other I-League clubs. We play in the playground where Mohun Bagan and Bengaluru FC also play. We are just very new in the system."

There has been, Royte says, a paradigm shift in north-east football in terms of ownership and management. "I hope that new clubs with new investors will come up, or existing clubs may re-orient themselves so that there is accountability and responsibility of running clubs ... instead of running it through an NGO or a community-based organisation, running it through a professional body. This will also change the scenario of north-east football."

Of the scattered pockets of football identity that are being created in the region, NEROCA are perhaps the bravest. Manipur's turbulent political climate does not make for the best environment to create an entity based on an intangible called hope. Yet they are on their way. Arun Thangjam, one of the co-owners of NEROCA FC, says the aim is simple: "Our main objective is that we should have an I-League team so that our boys can have a facility to play for our state also. So far, no club from our state has participated in the I-League even though we produce so many players."

Thangjam is one of seven sons of club president Thangjam Dhabali Singh, who set up the team over 50 years ago. The family own the Classic Group of Hotels, which are the main sponsors, but two years ago they turned the club into a private limited company to compete in the I-League second division. At the Durand Cup last September, NEROCA defeated Aizawl FC in a group match that Novy Kapadia remembers watching. It sounded and felt like a Kolkata derby, he said, "without the fighting in the stands."

Kapadia remembers visiting the NEROCA changing room after the match. "The owner promised them bonuses -- not big amounts, this is not the owner of the Intercontinental Hotel, it was 2,000 rupees per head, but [there] was so much emotion there." New state rivalries are building, Kapadia says, and the defeated Mizo fans had left the stadium, "boys and girls crying."

Financials will always be the challenge for north-east clubs, but as Larsing says with rueful romanticism, "Everyone has their passions." The owners of NEROCA and Aizawl are "hugely committed and enterprising people who have their own businesses and are consciously deciding to support football. We want to see football in the region to reach greater heights and to participate strongly because it helps Indian football."

Lights, camera, action

As the floodlights come on, Aizawl's Lammual Stadium, aka the Assam Rifles ground, becomes a beacon visible across the valleys. When the amused Assam Rifles guards let us into an eerily quiet and empty ground, the lone human being in sight is a vendor selling lotus seeds.

There is light and activity at the bottom of the main stand. The players in their changing rooms, the match commissioner ensuring that his countdown clock, synced with the Zonet TV crew, follows the schedule glued to his "office" door. The match balls are being tested for air pressure, and the referees are pulling on socks, giving their calves a good rub. The room smells of Iodex.

Lalrawngbawla, aka Bawla, match commissioner by night, school commissioner by day, has a cheery confidence. "We have the best league in India."

In the changing rooms, it is prayer time, part of every team's pre-match ritual. Of Mizoram's 1.1 million people, 87 percent are Christian, the church forming the core of a society built on the relationships and community. The MPL has become part of that larger community, moving effortlessly through church and state. It helps that MFA president Lal Thanzara happens to be the chief minister's brother. The eight participating MPL teams are neighbourhood clubs, and as the competition heads towards its knock-out phase, the areas in the reckoning hold prayer meetings seeking a hand from God.

With less than 10 minutes for Chanmari vs. Aizawl FC to begin, the main stand fills, men, women, children knowing where each side's fans must sit. It's a weekday, it has rained, but around 700 people turn up. The match is played at a furious pace, with speedy passing, muscular tackles and chanting fans. Melodies you recognise, like "Glory, Glory Hallelujah" sung in Mizo with the lingering rumble of the darkhaung, a large brass drum.

The Mizoram Premier League lasts about four months and features eight teams from Aizawl. This may appear to limit teams from elsewhere, but almost one-third of Mizoram's population, and maybe almost its entire industry and business, operates out of the district. Few other Mizo towns could afford to support teams in the competition. Budgets vary, with clubs like Chanmari, from an affluent part of town, spending around Rs 15 lakhs per season; at the most frugal end this season are Dinthar FC, who manage with around Rs 5 lakhs. Club owners, some who are local businessmen, put in their own funding, rope in other friends and reach out to sponsors for extra leverage. Door-to-door household donations are part of fund-raising. Tvanlalhuma, a Dinthar founder-chairman, says his club represents around 750 households and 2,000-odd people.

The MPL has become a major event in an otherwise quiet Aizawl calendar. It has advertisements, hoardings, female models to represent the clubs, merchandise, a music video and every two years a "Mizo Idol" reality TV singing competition show on Zonet.

The league came into being among three friends in January 2012 during a trip to Delhi. Tetea and two thirtysomethings, L V Lalthantluanga, aka Tato, and Lalnunpuia, aka Mapui, had travelled from Aizawl to watch Bayern Munich play in Delhi. (It was, not incidentally, Bhaichung's testimonial match.) Talking about Mizo football, Tetea says they saw that some Mizo players would earn "a lot of money," but others didn't have enough "to even pay for boots. We felt that if we can provide them with the platform, they can compete with the rest of the nation."

What has made the MPL different from the many annual tournaments that are held over the region is non-stop visibility. Every MPL match is telecast across Mizoram on Zonet Cable TV. The game changer was Zonet's gamble of a financial commitment to the MFA of Rs 25 lakhs per year for five years for the telecast.

The dream was to create a league that was at least semi-professional, with the coaches and the players paid. "We tried hard for that. I don't know where the money came from," says Tetea, laughing. "It was a gamble from our side and from Zonet's." He is now sure of this: "if you wait for the money to come first and then start a league, then you will never start it," he says. In a state without multinational companies or external investment, it's a fair bet either way.

Much of Aizawl clings onto slopes, ascending and descending, the town resolutely hanging on to the edge. Each level is connected to another above and below with steep flights of stairs. They save time from the extended walks around gentle hairpins but destroy the lungs. The views are killer. Like the one from the roof of Zonet's offices in Zarkawt, where there are more satellite dishes to be found, and a few clotheslines.

Tato, Zonet's general manager, understands the demands of television and calls his company's MPL production a movie-style "lights, camera, action." When the first artificial turf with floodlights was installed in the state in 2011 at the Lammual, "the government provided the lights, we came in with the cameras, provided the television. The action is the football." Zonet's TV production is completely local and packed with familiar programming.

Production director Khawlring "Mapuia" Lalhruaitluanga sits in his control room under a stand, picking footage from three cameramen around the ground. Presenter K Vanlalruata, who played cricket as a student in Bangalore, does longer pre-match shows on weekends, and ground reporter Sabina Lalnunsiami is in charge of post-match presentations, before a sponsors' board like they do everywhere. There are four statisticians per match, and Tetea is not shy when he says, "Our stats are better than the ISL's."

After games, Sabina interviews the man of the match winner and rival coaches who receive the "match monies." The amounts may be modest, 3,000 rupees and 2,000 rupees each, but there is a gleaming urge to be slick and professional. Once the monies are distributed, a sponsors rep pops in to quickly take a selfie with the awardees and the awarders, which is quickly out on the TV screen and social media. It's live television, so there can never be dead air.

"Whatever we have we push it to the maximum," says Lalnunpuia, the tech guru at the Zonet MPL project. He is speaking about the MPL but could be talking about Mizoram football as well. A maximum created out of a minimum. Tato of Zonet says, "Everything has to be done dot to dot, this is football as entertainment ... we still have a long way to go, we're looking at international levels because everyone watches the EPL here." Every season, he gives football-stage-television-performance speeches to his players. The usually shy Mizos, he finds, may say they don't really want to be on TV, but "when we push them they are very happy deep inside. When it comes to TV, you command people." Five seasons on, Mizoram football commands sporting discussion in the state and outside it. Says Tetea: "Apart from football, I don't see any other fields in which we compete against the rest of the nation."

The MFA annual fixtures list includes a first division league just below the MPL, Cup tournaments and age-group events for juniors (under-17) and sub-juniors (under-14) in the districts as well as village competitions. In 2015, Mizoram was one of seven states selected under the FIFA-AIFF State Football Development programme. The MFA's Mark Lalduhsaka says, "We don't get our chief ministers or our ministers in the national papers, but we get our Mizo players in the national newspapers. ... Football is one of the most important industries in Mizoram, and the brand Mizoram goes with football." To the "legacy clubs" of Bengal and Goa, this may seem a mighty claim, but to the outsider, parachuted into the MPL, it looks like Mizoram football has found the formula and knows that it works.

Just after a 0-0 half-time the sharp contours of a game under floodlights begin to dissolve. The clouds, we discover, are floating up the hillside to pay Lammual a visit. Within minutes, they have drawn together their thick cloak and brought the game to a standstill. The players turn invisible, swallowed by the clouds. Not the fluffy stuff city dwellers see far overhead on sunny days but a white-out of vision. It lasts, Bawla's trusted timekeeping informs us, for 33 minutes. "Clouds stopped play"? Nine minutes before full-time, Chanmari scores and wins 1-0, beating the defending champions. When the goal came, they say you could hear Chanmari the neighbourhood, 2 kilometres uphill from the floodlights, shrieking with joy.

The next evening, Lalthanszama Vanchhawng, aka Zama, the AIFF-MFA's Grassroots development officer, watches 6- to 12-year-olds gambol around the ground. Zama is also a D-licence football coach, serves on an MFA committee, is an MPL commentator- pundit, administrator of a website called Zofooty.com and Zonet's sports editor. He also holds an M.S. degree in biotechnology but doesn't appear to have any more fingers left to stick into that particular pie. This is Mizoram football -- everyone multitasks. Zama has been with Grassroots since its 2012 inception.

This year applications hit 1,000 and final registrations were 292. "Parents want their sons to be Jeje," Zama says. Jeje Lalpekhlua was national U19 captain and now, as an India striker, he has scored 17 goals in 39 full internationals. Jeje told Hindustan Times' Brunch magazine that he was inspired by Mizoram's first professional, "Mama" Malsawmtluanga. "When Mama signed up for East Bengal, we discovered that a player from our state was playing in matches telecast on TV. All of us dreamt of becoming Mama, growing up to become pro footballers one day and playing in the I-League."

Jeje today is one of the highest-paid Indians in the I-League. He comes from Hnahthial village, 150 kilometres south of Aizawl, where, no doubt, many boys now watch the MPL. Television, as Tato said, commands people.

It is our last evening in Aizawl. The light is dropping around Lammual, and the mist is gathering. Everything here goes dark quicker than it takes for the streetlights to come on. The boys in their red bibs are listening to final instructions from Zama and then bunch together to end the session with a final chant. Aizawl's purple dusk is filled with still, cool air and the sound of traffic traversing a damp road. Young voices cry out "Grassroots!"

This is Mizoram, where grass finds it hard to sink its roots into the quick-moving, fluid ground. Football's roots here are made of tougher stuff and have dug themselves deep. The maximum out of the minimum. This is where north-east football is. And where Indian football needs to go.

All football-related statistics provided by Gautam Roy.