|

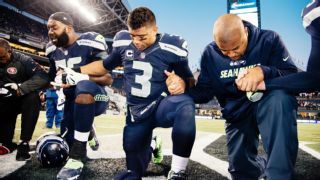

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's Jan. 4 Championship Drive Issue. Subscribe today! AT 9 A.M. ON Sunday, Oct. 18, after a choir of serene, smiling Christians sings a few songs about Jesus' love for all people, a man takes the stage. He's a dead ringer for the actor Patrick Fugit, with black plastic-framed glasses and a haircut that can best be described as Fall Out Boy's Pete Wentz circa 2006. We're at City Church, a sprawling, squat structure in downtown Seattle. Donation forms in Seahawks green rest on the seats. The man's name is Judah Smith, and City Church is his church, and he is the personal pastor for Seattle's quarterback, Russell Wilson. The sermon is about to start, but first Pastor Judah, who is being broadcast on-screen from the Kirkland campus, addresses what's on the mind of his faithful, a full half of whom are wearing Seahawks jerseys -- mostly Wilson's No. 3 but a fair number of Marshawn Lynch 24s and several 12th-man 12s. In four hours, jerseyed faithful will be cheering on their 2-3 Seahawks against the undefeated Panthers. Pastor Judah reminds us that at this time last year, five games into the season after winning Super Bowl XLVIII, the Seahawks were 3-2. "Three-and-three is a good place to start to get us there," he says, and everyone laughs and then everyone prays. Wilson is at the Kirkland campus himself on many Sunday mornings -- he doesn't live far, just over in Bellevue, where the other Seahawks live -- but never on a game day. On game days he wakes up with the rest of the Seahawks in a hotel in Bellevue. They gather Saturday evenings to talk strategy. They have chapel together at 9, and they have a curfew of 11. By Sunday morning, they're at the breakfast table at 9. By the time Judah Smith's service gets going today, the Seahawks already have had their breakfast and treatments and are preparing for the game. When he is here, Wilson stands in the front row and sings with the music, following along with lyrics that flash on the screen before the congregation. He raises his hands to the heavens, and he sways. He doesn't stand out too much, because even though he's a quarterback with great gifts, he's short. Wilson was drafted in 2012, 12th in the third round, part of a Seahawks class that one analyst scored a C and another an F. This was fine with Wilson. He doesn't mind that no one saw him coming. It plays well into his narrative that he was chosen for this, that God sent the world a diminutive man at 5-foot-10, that he was sent with an undeniable cannon of an arm to make the world take notice. His mother likes to quote Samuel 1 16:7, "It's not the countenance of a man nor the height, but the heart." Samuel said this when he was anointing David as king. You should not underestimate the impact the David and Goliath story has had on Wilson.  When he's at church, maybe he thanks God for the position he's been put in. Maybe he thinks about his father, who died before he could see his son make it to the NFL. Maybe he prays to be able to lead. Wilson has said he wants to lead the fans and be a light unto the rest of the NFL. He's said he wants to lead his girlfriend, the R&B star Ciara, and make his relationship a celibate example for other Christians. He wants to be perfect, and that was a wonderful thing just a couple of years ago, but something changed around the time Wilson tried to fire a ball to Ricardo Lockette at the end of last season's Super Bowl, only to have Malcolm Butler make the play of his life. By Wilson's third step toward the sideline after perhaps the most famous interception in the history of the game, he heard God's voice tell him that he -- that God -- had sent the interception, and along with it an opportunity to lead. Wilson said this in front of a crowd at The Rock megachurch in San Diego in July, and it seemed like a rational explanation to him, maybe because, how else could you explain it? The people who know him best say this kind of response is typical of his single-mindedness and confidence, of his tendency to fix his mind on a path and never waver. But it was with these comments about the divine interception that the story of Russell Wilson began to wear thin on those who'd been devoted to it. He was talking about God in a way that was beyond the usual quarterback pointing toward the sky. Football is full of religion, yes, but Wilson wasn't just giving the glory to God. He was handing everything over to God. Wilson was seeing himself not as a quarterback who is religious but as a Christian sent by God to become a quarterback and a Christian example. Fans had once accepted Wilson's overt religiosity, but now some began to widen their eyes and step backward with their hands up, like, "Whatever you say, buddy." Loyalty wanes in the face of defeat. In 2012, Wilson was called to Seattle, the city on a hill -- a city that was longing for the kind of leadership he wanted to provide. When coach Pete Carroll arrived in 2010, the Seahawks were fresh off a combined nine wins in two miserable seasons, and the franchise had no defining superstar. Then came Wilson. In his first season, he led the Seahawks to 11 wins and a playoff bid. Then a Super Bowl win. Then a Super Bowl loss. Today fans wear No. 3 jerseys on the streets, but Wilson still seems unknowable to them. They love talking about Marshawn Lynch's Beast Mode and Richard Sherman's smile and outspokenness, but nothing about Wilson stands out except for his talent, work ethic and his religiosity, which are considerable but are not really brands you put on a T-shirt. The cab driver who takes me from the church to the stadium on that Sunday in October tells me that he doesn't know whether Wilson will show up today, meaning of course he'll be there, but will he show up? Someone close to the Seahawks organization tells me the team has lost its heart since the Super Bowl and is having a hard time getting it back. And a millennial drinking a morning beer near the stadium asks me, "Do you know he doesn't have sex with his girlfriend?" I assure him I do. "Do you know his girlfriend is Ciara?" he continues, pulling up a picture of her on his phone. Wilson's persona seemed fine when the Seahawks were winning, but now fans need an explanation. God's sending interceptions isn't going to reassure them about the future -- even though that future, in just a few weeks, will see Wilson playing the best football of his life. In comment sections, Wilson was ridiculed ("Didn't he learn from last year? You're not gonna score if you get cute with it. You gotta POUND IT IN."), and blogs capitalized with religious bigotry click-bait -- "Russell Wilson Thinks He's Jesus," read one. "God Doesn't Belong in Russell Wilson's Contract Negotiations," read another, a reaction to Wilson's suggesting that if he didn't get the contract he wanted in the offseason, it was simply God's will. (He'd sign a four-year, $87.6 million deal.) In the mainstream media, Wilson was a robot who wouldn't answer questions authentically. He was too close with the front office, he wasn't black enough, he was boring. Meanwhile, the Seahawks' uncharacteristically porous offensive line wasn't really allowing him to do his job early in the season, but like a good leader, like a good Christian, at his news conferences, as he was leading the league in getting sacked, he was taking full responsibility with a host of clichés: "I'll do better next time." The game of football is unpredictable, the media are fickle, but there is one thing Wilson can control: himself. Wilson is someone who endeavors to play great football so that he can continue to have a platform upon which to display his leadership and his faith. Understand this and you're closer to getting to know Russell Wilson than you were before.  CONTRARY TO POPULAR belief, CenturyLink Field, formerly Qwest, née Seahawks Stadium, was not built to hold in noise. It was built to acknowledge that it was a stadium in a city, and so it was created with a view of the skyline on the north end and with 70 percent of its seats having coverage and protection from the elements on the south end. This is Seattle, after all, beautiful and wet. But an incidental result of this shape is that the stadium can hold in an inordinate amount of noise -- the Pacific Northwest Seismic Network regularly monitors the impact of the noise, which can shake the actual earth -- and it inspires the fans to make even more, and it makes being on the visiting team far more intimidating than it normally is, which is very intimidating. And if you're the quarterback of the home team at CenturyLink, you learn to absorb the cheers of support while discerning the noises you should pay attention to on an average deafening game day. In the bowels of the stadium, the Seahawks psych themselves up for the game against the Panthers. Wilson discusses strategy with the coaches, who will later whisper those reminders through the sound system installed in his helmet. It is helpful to think of Wilson as a man who loves authority and a man who is accustomed to hearing guiding voices in his head. He often refers to God as Father, despite all the other ways you can refer to God, not because he no longer has one of his own but because the one he did have was such a godly figure. From the time they could walk, Harrison Wilson III worked to make sure that all three of his children were watched and cared for and educated and groomed to be the wholesome, God-fearing athletes they all became. Harrison wanted a better life for his children, and his children wanted him to know that he had provided it. Harrison grew up in Mississippi in the 1950s. He'd become a lawyer. Russell's mother, Tammy, was an emergency room nurse and just as devout as her husband. They sacrificed to put their kids in private school and live near it, in a nice house at the end of a cul-de-sac in Richmond, Virginia. Harrison didn't want his children to have to work as hard to be exceptional. He wanted opportunity to find them. He died from diabetes-related complications in 2010. Since then, Wilson has found comfort in the original Father, but more than that, he has positioned the men in his life as fathers as well. Pete Carroll is a father figure. Wilson's high school coach, Charlie McFall, is a father figure. His agent, Mark Rodgers, is a father figure. (Mark's son, Matthew, is his manager, and he's like a brother.) Fathers figure prominently for Wilson, but none of them is like his own. He quotes his own father frequently, particularly one phrase about there being a king in every crowd. He misses him every day, which is a thing he says to everyone who will listen, and spends his life fulfilling his father's truncated dreams. Harrison III wanted to play in the NFL, but his father, Harrison Jr., the former longtime president of Norfolk State University, urged him to attend law school before trying out. Now Russell would like to be the king in the crowd. He would like to lead. That's a word he uses a lot, "lead." This past summer, Wilson's use of this word landed him headlines. It began like this: Pastor Miles McPherson, a former defensive back for the Chargers (and now the lead pastor at The Rock), met the quarterback back in 2012, at a prayer breakfast the day before the Wilson-led Wisconsin Badgers played in the Rose Bowl. Wilson was so respectful for a young athlete. Pastor Miles couldn't get over what a great kid he seemed to be. They saw each other next at the Pro Athletes Outreach conference, an annual gathering to "unite a community of pro athletes and couples to grow as disciples of Jesus and positively impact their spheres of influence." Pastor Miles and Wilson grew closer, and when the Seahawks came to San Diego, Pastor Miles did chapel for them. In the summer, he asked Wilson if he could interview him onstage in front of the congregation. Wilson said yes. This was in July, after the ill-fated Super Bowl and after many attempts at teamwide healing from it. (In April, Wilson had chartered a jet to take his teammates for a post-loss therapy session in Hawaii that, in a Sports Illustrated story, ends with everyone in love and cuddling in a football game on the beach.) In front of a large crowd, Wilson took a selfie with Pastor Miles and settled into an armchair. From the stage, Wilson said that on his way off the field, Jesus told him that he'd sent the interception so that he could see how Wilson would react, but also so that Wilson would show the world how he'd react. He said this not with arrogance but with the casual matter-of-factness that only someone speaking to fellow believers can pull off. "There's a silver lining," Wilson told the crowd. "Jesus is so amazing." In a video of the talk, Wilson also told the pastor he had predicted that he would end up with Ciara long before he met her and, when he did meet her, that God told him he needed to lead her too, which to Wilson meant that they should not have sex before they wed because they are Christians. "Right now?" Wilson pretended to ask God, and the crowd laughed, because she is beautiful and maybe God could have asked a little later? But Ciara is a believer in God and also a follower of him ("There's a difference," Wilson says), and she signed on to this. They were going to do things God's way. "He has anointed both of us," Wilson told Pastor Miles. "He has called us to do something miraculous, something special." During the interview, Wilson was loose and fun and charismatic. He made off-the-cuff jokes while being as sincere as he always is on matters of faith and love and football. His smile was relaxed and welcoming. But after these comments, the punishment began. Few journalists remained straight-faced as they reported the celibacy news. Comments sections were full of eye rolls. Back in the stadium on this October afternoon, Wilson doesn't listen to the fans screaming as he goes over the plays. He sticks with his coaches and he puts on his helmet and he listens. It is helpful to think of Russell Wilson as someone who hears voices far louder than those in the stadium, no matter how the thing is rigged for distraction.  WILSON OFTEN KNEELS in prayer with like-minded teammates after wins and gives public praise to God. He'll maybe point a finger to the sky in a game or look up. His expressions aren't particularly raucous, win or lose. Last season, after the Seahawks beat the Packers in dramatic fashion, securing a trip to the Super Bowl, an emotional Wilson said, "That was God setting it up, to make it so dramatic, so rewarding, so special." This season, in Week 2, after the Seahawks lost to the Packers, Aaron Rodgers fired back -- God, he said, must have been a Green Bay fan that night. Rodgers believes in God, but he doesn't think God cares about the outcome of a football game. To Wilson, God cares about everything, particularly the people he has anointed to lead. Wilson was saved on a hot summer night when he was 14. He was at a football camp at the University of Virginia, and that Saturday night he had a dream that Jesus walked into the room and told him he was preparing Wilson for a time when his father would no longer be around. The next day in church, which he usually endured while fidgeting and which he attended only to see this one very pretty girl, he felt the overwhelming spirit of the Holy Spirit. Peace flooded through him, and he cried. His life changed fast after that. He'd always been a leader, but more in the manner of a bully. Back when he was in second grade at the Collegiate School in Richmond, he approached the teacher who acted as quarterback for the little-kid football games during recess and said, "Coach, I think I'll take over." He would exclude some kids from the game, until one day his middle school head, Charlie Blair, told him he had a gift for leadership, and if he could turn his negative behavior into positive behavior, he could be very effective. Before that conversation, he was a cocky kid. After that, he was humble. Wilson has been coachable from the beginning, always looking to authorities for advice. At NC State, where he started his college career, one of the staffers called him "high-maintenance" as a joke, and he wouldn't let up. He kept asking if it was true and how he could fix it. He didn't want to be anything that wasn't completely admirable. In high school, he'd show up for 6 a.m. practices, the other guys bleary, Wilson with his swift hand-clap, saying, "I feel good today! Yes, I do!" He would do one-legged squats, and if he felt like he didn't dip low enough on the fourth squat, he'd do No. 4 all over again before moving on to five. Teammates worked to impress Wilson, showing how much weight work they could do without grumbling, working hard toward their collective goal. At Collegiate, Wilson is still known for his charisma, for being the most competent athlete around and for never carrying himself like he was. During his high school news conferences, he said the right thing. He gave all the credit for a win to his teammates. He took all the blame for a loss. His father had him practicing for news conferences from age 7, so there was little that could faze him or alter his demeanor. But he always had charisma. His coaches cannot reconcile the Wilson they know with the robot that NFL reporters sometimes describe. Robots don't get elected captain of the team as a junior. Robots don't survive as one of the only black guys on the high school football team. At that age, he had a clear plan for his life. He would be the shiny, clean-living, God-fearing leader of whatever team God chose. He would play better than well. He would be a clear demonstration of calm within whatever storm might arise. He met a girl from St. Catherine's, Collegiate's rival school down the road, when he was 15, and they continued dating through high school and through his three and a half years at NC State. He played baseball there too, but his football coach didn't like him leaving for spring training and missing practice. His backup, Mike Glennon, had two years of eligibility left, which the program wanted to take advantage of. So between that and spring training, NC State granted Wilson his release. He had already earned his degree in communications and was taking postgraduate classes. He went to Wisconsin. But he didn't move on easily. Never had he endured anything but the glow of approval from authority figures. Now he was the subject of a terse news release wishing him the best of luck. How could he do it all right and still have a falling-out? He was stung, listening only to Yolanda Adams, a Christian singer, playing "I'm Gonna Be Ready" over and over. Strength to pass any test, I feel like I'm so blessed, With you in control, I can't go wrong, 'Cause I always know I'm gonna be ready. He had a successful season at Wisconsin. A couple of weeks after the Rose Bowl, he married the girl from St. Catherine's in an elegant ceremony with a black-tie reception at the Country Club of Virginia with full-scale trees in the place and a swing band that played all night. They put off their honeymoon so he could train for the NFL draft. And everyone danced and swayed and clinked glasses, and yet some would later wonder whether this was the greatest idea. They were young to get married -- he filed for divorce in 2014 -- and Wilson was already married to football. And he'd always be most devoted to God.  AGAINST THE PANTHERS on this October afternoon, the Seahawks dominate until they don't, another baffling fourth-quarter loss that makes the people in the press box throw up their hands. Wilson has recently picked a Bible Verse of the Year to share repeatedly on Twitter. It's John 3:30: "He must increase, but I must decrease." Someone, a fan, tags Wilson on Twitter and asks if perhaps he's decreased quite enough for one season. After the game, in the locker room, Wilson stands talking to Doug Baldwin, his wide receiver and a fellow Christian. He looks morose. He runs his hand through the rooster top of his head over and over, rhythmically, from his forehead to the nape of his neck, forehead to nape. They speak in a soft tone. Maybe in this moment Wilson is faltering, wondering how this is happening, wondering what Jesus' message for him might be. Or maybe in this moment he's leading and guiding Baldwin toward Wilson's favorite of sports clichés, which is that you have to make every play a championship play, yes, and every game a championship game, yes, but you also have to take it one game at a time because at the end of the day it is what it is. When Wilson does finally undress, it's as his teammates are walking out. They put a hand on his shoulder as they pass, and he bows his head and mashes his lips together but is otherwise expressionless. He puts a blue towel around his waist, and he goes to take a shower, but he gets derailed again and sits down in his locker and puts his forearms on his thighs and clasps his hands and stares off. In the news conference room, Pete Carroll answers questions and leaves, and in walks Wilson. He's not in his usual postgame suit. Instead, he's wearing a black trench coat with the collar up. His eyes are shiny, and there's mucus in his nose. His smile is polite and faint. Someone starts: "So much was working early on. You throw the ball to 88, you got the touchdown to Ricardo. Does that make it even more frustrating, that so much was working well early on?" "Yeah, we did a lot of great things, and we didn't do enough great things. There were a few things that, you know, we could've done a little bit better. You know, myself included, especially, and I feel like you just find a way. You know? So like I said, just stay the course." "What's the mood of this team right now?" someone else calls out. "You know, the mood, I think ultimately we're obviously disappointed in losing. You know, you never want to lose." It goes on like this, and Wilson answers each question, his expression unchanging. When all the questions are answered, he says, "Thank you, guys. Go Hawks. Pass the peace," and he leaves. A reporter in back of me says, "Jeez, that guy." Another: "I got nothing." And another, "It's like interviewing a corpse." And the reporters chuckle and begin to wrap up their equipment. But what exactly was Wilson supposed to say? That they lost their heart? That they were a championship team and they weren't exactly sure what the hell was going on? That healing requires far more than a beach vacation? That he isn't completely sure that last Super Bowl play was the right one? That asking that question rattles everything he thinks about the way he receives those voices into his head and into his helmet and into his heart? That he'd give anything to hear his father remind him, not from his best seat in the house in heaven but from here on the ground, that he is the king in the crowd, that he can rise above his circumstances, that this is just another test? Which was the question that was asked in that room that called for a real intellectual and heartfelt answer, an answer that defied cliché? If it were asked, I did not hear it, and I was sitting in the front row. And if it were asked, he likely wouldn't have answered it, not in the way they wanted. He'd have given the obvious answer. That's how he moves forward. The media aren't a bridge to his fans. He conveys himself through his sportsmanship and through his Instagram, which is filled with the delighted faces of sick children and their parents, whom he's given 10 minutes of relief from their worry and terror with a visit. He conveys it by getting interviewed by someone he trusts -- a pastor, a clergyman, a father -- and sending Jesus' message out to the world. Quarterbacks need only be interesting on the field and not be violent or unlawful off it. Trent Dilfer, an ESPN NFL analyst and a former quarterback, told me that quarterbacks have to be good at 40 things. Wilson is good at 39 of them -- the 40th is being tall -- and his 39 are better than the average 39 because of how hard he has to compensate for that very significant limitation. So many people told him he could never make it as a quarterback. So many people suggested he do like all the other short and talented guys, which is create a better avoidance game, be the guy running away from all the other guys, particularly the 6-7 ones. All of this overcompensating, creating the avoidance game, surviving under pressure, helped Wilson get here, which, remember, was a serious long shot. Now, it could all be just an impressive act of compensation, as Dilfer suggests. But indulge me for a moment and imagine that Wilson is right and that all of this has worked out so well because he was anointed by God for it. The seed of Wilson's talent may be his confidence. But his confidence is straight from God, from the reassurance that comes with the kind of belief that infiltrates Wilson's pores. Those voices in his head, the ones that began with his father whispering into his ear and became Jesus visiting him, which became his coaches inside his helmet -- those haven't let him down yet. He has no regrets about that final Super Bowl play, because to be Russell Wilson is to acknowledge that you are but the lucky son of many fathers, and to wonder whether they got that wrong is to shatter the foundation of every life decision you make. To be Wilson is to have an utter belief that the voices you hear will never steer you wrong. Wilson isn't a robot, and he isn't a corpse. He has a carefully modulated tone, which he's been practicing since Charlie Blair called him into his office at Collegiate and told him how to be a leader. He shortened his range of reaction, truncating the spectrum to a range of, say, plus or minus three, so that he doesn't flip out when he loses, and he doesn't flip out when he wins. People who stood in his hotel room after the Super Bowl loss confirm that he was still plain old Russell, not too emotional, not outwardly heartbroken. Leaders don't get re-elected when they're too emotional. He doesn't want to be a problem in the media, but being boring isn't a concern. Go watch Wilson onstage with Pastor Miles. Go watch him dance with Ciara at the Kids' Choice Awards. He is as charismatic as he needs to be for the people he is leading.  AFTER THE GAME, the city is deflated. The clocks haven't changed yet, but it's getting darker earlier. The fans, so boisterous just moments before, file out of the stadium, quiet now. Back in the locker room, Russell Wilson finally does shower. He puts on a suit, and he goes to a restaurant near where he lives in a beautiful mansion overlooking the water. The restaurant has a private room, and he often has dinner here after games with important people who have watched the game from his box. This week he's supposed to meet a few supporters, a few members of his management team and family and friends. These people wonder whether Wilson might not be in the mood to have dinner. But of course he would. It never entered the realm of possibility that he would not meet his obligations. It never entered the realm of possibility that he would not show up. He has a steak, and the people who dine with him see a version of Wilson who's just as charming as he'd be after a win. He shakes hands and talks, and when dinner ends, he gets into his car and drives down the 405 and gets off at Exit 7 to the Seahawks' practice facility. It's dark now. Sunday is coming to an end. He spends the next two hours watching video from the game. The next day, a group of men take to their radio jobs and spend the day eviscerating Wilson and the offensive line and then the defense and then the coaches and back to Wilson again. These people -- not just the hosts but also the people who call in -- sound angry. They are angry at Wilson. They are angry at the offensive line. This is maybe the worst thing that has ever happened to them, which is exactly how angry they are. It's going to be a short week. The next game is Thursday, just three days away, but the Seahawks are grateful for the quick turnaround. They need a victory to take this taste out of their mouths. And they get it, against the 49ers. A month later, though, they'll really hit their stride, and how: Wilson will take that cannon of an arm and remind the 49ers again, followed by the Steelers, Vikings, Ravens and Browns in quick succession, whose team God is on. He will reassure the people of Seattle that they are not wrong to believe in him. He will excel in ways he never has before, surprising his critics yet again, staying in the pocket, scrambling less, throwing 19 touchdown passes and zero interceptions in the five-game winning streak, pushing his name into MVP conversations with Cam Newton. He will provide the leadership Seattle craves and make the playoffs a possibility yet again. But first, the next morning, Russell Wilson gets up, and he prays to be the king in the crowd, and he goes back to the practice facility for postgame treatments, and he stands up and claps one big loud clap, and he gets back to work, ready to listen, ready to lead.

|