|

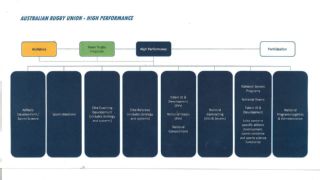

Given the events of the past six months, or even 12 months, rugby fans in Australia are struggling to feel overly positive about the current state of the game. Talk to any rugby supporter anywhere, be they players junior or senior at club or sub-districts level, in the city or the bush, or someone in any way involved in the rugby community and you'll hear a constant refrain: Things have never been this grim. One of the common themes is this: Where is the next generation of Wallabies coming from? What is happening at the grassroots levels to foster player development in a market in which rugby league is currently rugby's far more attractive, and completely dominant, direct competitor? And that's not even considering AFL or soccer. Late last week, the Australian Rugby Union announced it was axing the Western Force from Super Rugby under the governing body's agreement with SANZAAR to reduce the competition from 18 teams to 15. That decision has split the Australian rugby community, with the players and Rugby Union Players Association united in their belief that Australian rugby can sustain five teams while administrators and officials say there is no longer the money or the talent pool to field five competitive franchises. On performances alone, it's hard to argue with the officials. But when the ARU chief executive Bill Pulver and chairman Cameron Clyne first fronted the media back in April to explain the Super Rugby situation, at the now infamous "48-72 hours" press conference, there was a constant referral to the term "high performance".  "The money we'll save by cutting a team will be directly reinvested into grassroots rugby and our high performance systems," the duo insisted. "High performance" was mentioned ad nauseum. On the surface of it, the ARU's willingness to reinvest the money available after axing the Force - the financial benefit of the decision, as Clyne explained it - will be good for the game in Australia, especially in the long term. That is, of course, providing one understands what "high performance" actually means. At the aforementioned ARU April press conference, the term appeared to be used as nothing more than a bit of PR spin. So ESPN set out to better understand the term, and just what it means for Australian rugby. "I believe what happened was that they sought a term that differentiated that part of the game [from] the community or the participation side of the game," ARU High Performance manager Ben Whitaker tells ESPN. "It was about differentiating the participation side of the game from the so-called core professional when [the game] went professional. "And then people started treating it differently; in a lot of other sports, high performance probably refers directly to the athletic side of the sport as opposed to the overall one. If you look at [the diagram, see below] that's how we're set up and ... we oscillate between using the terms "elite" -- which some people like and some don't -- and "professional" ... but [that] doesn't define everything in there because there's some non-professional elements to that system. "We refer to it as the 'national high performance system' ... and within that system we interact to produce, ultimately, on-field results. The challenge is to get a lot of those systems integrating consistently with enough resource, intellect and knowledge so that you can allow teams to win."  The diagram above, provided to ESPN by the ARU, shows the various operating areas that fall under high performance and, in turn, are used to help to develop sevens and Super Rugby players, Wallaroos and Wallabies. Another way of understanding the system it to consider that participation sits on its own but ties in with the overall system as participation rates act as the backbone of the system. If the level of young boys and girls, and men and women, playing the game decreases then so too does the capacity for competition, development and, eventually, the production of professional players. In terms of overall participation rates, Australian rugby is currently experiencing growth in some areas, decline in others. Australia's women's sevens gold medal at the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio de Janeiro has had major impact on female participation rates but, on the flipside, numbers in the sub-districts competitions, particularly in Sydney, have been on the slide. For example, Sydney's Division 1 competition has been cut back from five grades to four (plus colts) as clubs struggle for numbers. Country rugby is also battling, though some of that can be attributed to population flows. It's not all doom and gloom at the lower levels, with club rugby experiencing a resurgence as has been widely reported this year. Having received next to no funding from the ARU over the past few seasons, Sydney's Shute Shield clubs have taken it upon themselves to ensure their survival and, in doing so, that are playing a leading role in the overall development of professional players. But they are also going through a period of change as the competition is increasingly skewing younger, and players continue to give the game away earlier than they have in the past in what Whitaker believes is "a consequence of going professional"  "I don't know how aspirational guys were in the past, but the aspirational element hasn't changed," Whitaker tells ESPN. "It's just that 'making it' now is playing professionally whereas in the past 'making it' was a long career playing first grade and maybe playing for your state, and then maybe the Wallabies. Now that's a little bit different. "So I think that's been the case for a long time and that's why we've got a very young demographic playing Premier Rugby, which puts the pressure on coaching. And I go back to when my brother played at Randwick: The guys he had around him coached him more than the coaches or coach, whereas these days the coach has to do a lot more to support player development than they did in the past because they don't have the experience around them to assist." That's a problem reflected further up the chain by the fact that two of Australia's five Super Rugby coaches last season were born and raised outside of Australia, with Daryl Gibson and Dave Wessels from New Zealand and South Africa respectively. The ARU has since looked to address this lack of coaching development with the appointment of former Wallabies back Rod Kafer to head up its National Coaching Advisory Panel. Kafer says the "problem" is as much about education as anything. "I think when we look at what Australian rugby has done over the last 20 years since professional rugby started, what's interesting for me from a coaching perspective is that when the game went professional the coaches who came into the game who were from a different career, who all of a sudden had a career opportunity to coach, many of them came from teaching backgrounds," Kafer tells ESPN. "We had quite a few school teachers come in, as you'd expect, and there's lots and lots of examples; the thing that's happened as the game has evolved over the last 20 years of professional rugby, now we see our coaches coming in who are, more often than not, ex-players. We've moved away from the skill-set of teachers that we've had previously. And that's created a different dynamic in terms of the natural affinity of our coaches to educate and change behaviour of players. Teachers -- Eddie Jones, Graham Henry, Matt Williams -- there's any number in those early days; it didn't necessarily mean they were good coaches but it meant that they had a background in education and changing behaviour.  "Coaching recently, we've now got many ex-players who probably haven't had any formal training in education; so there's this recognition that we need to look at how we go about educating our current coaches and give them the skill-set that they've lacked simply because they haven't had some of that formal training; not in the tactics of the game of rugby, because they're experts in that, but in the concept of how to change people's behaviour through learning and education." An improved coaching base will take time to build and in turn filter down throughout the game, and that's not great news from a talent identification perspective as rugby seeks to make itself as an attractive option as possible -- particularly when up against rugby league. Good coaches and communicators can help sell the game, which at the moment, is no easy feat. A source currently experiencing the aggressive nature of approach from NRL clubs revealed to ESPN the extent of the pursuit while rugby "effectively sits on its hands", but Whitaker says the ARU has made a conscious decision against entering the space of contracting young players too early. "We enter that area probably around 14/15," Whitaker tells ESPN. "Research will say that is not too late because of market forces. The competition for talent in this country is enormous, as we all know; we talk about the football codes but it's far more than that. I think we're very conscious of the fact that A) some of the pressures on these kids in this country can verge on the irresponsible. And the other thing is that identifying a 13-year-old, and the correlation between identifying at 13 and then going on to be an impactful player at international level is very, very small. "There's also the other aspect where you go 'well, if I zero in on a 14/15-year-old and I work with them through five, six, seven, eight years I will probably get a result'. Whether it's the very best result you'll ever get with someone of this age, you don't know. We've had some really good successes there where we have gone in early at, say 14/15, and said 'hey, we'll work with these guys'. But then you get the criticism that you're just concentrating on a batch and not allowing entry later on. And you can't win that debate in this country because you're damned if you do and damned if you don't." The cold hard facts are that a lot of children growing up, particularly in New South Wales and Queensland, and even Western Australia to a lesser extent, play both rugby and rugby league growing up. But rugby league has the ability to promise a little more at a younger age, albeit in a reduced capacity going forward due to the NRL's decision to scrap its Under-20s competition. In a lot of cases at junior level when preteens and teenagers experience both codes, it's often said that rugby league is a player's first love and therefore wins out even if they have the chance to experience a state, or even Australian Schoolboys rugby side, as was the case with St George Illawarra Dragons and New South Wales Origin star Tyson Frizell.  But it's the cases of players such as South Sydney forward Angus Chrichton, who is touted as future Origin star after experiencing a breakout season in the NRL, that cause most frustration to Australian rugby fans. A schoolboy rugby star at Sydney's Scots College, Chrichton had all the makings of a ball-running back-rower, or centre as he played at school, at the top levels in rugby before Souths saw an opportunity and swooped. A recent segment on Fox Sports' League Life revealed how a well-timed phone call from Souths coach Michael McGuire planted the rugby league seed, and the Rabbitohs are now feasting on the results. "Someone like Angus Chrichton, who was after a fulltime environment and Souths were prepared to give him that, admittedly through the Under-20s competition to start with," Whitaker tells ESPN. "He wanted to challenge himself to break through probably sooner than we thought he would in rugby, and he's done really well. "Would he have made a really good rugby player? For sure. We talked about you go away in those formative years -- 18-21 -- when you really learn the game; if you're committed and you're in a good system and program, you learn the game -- particularly as a ball-running back-rower who needs to develop other skills. We pitched that to him, and I don't know if that weighed into his decision "So it's an ongoing challenge to keep those good kids. And when I say "keep", it's an interesting one. A lot of these kids who go to league are usually league players to start with; Angus not so, but the Tyson Frizells of the world are [league players]. A young kid, Cameron Murray, who was at Newington [College], a really good kid playing at Souths at the moment -- same again, a really good rugby player but a league player by trade. He's talking about coming back [to rugby] one day, but you don't know." Whitaker rightfully points to the likes of Ned Hanigan, Richard Hardwick and Jack Dempsey as players who have come through the development system, including Australia's Under-20s side, to become play in Super Rugby. But the Australian team failed again to make the semifinals of the Junior World Championship, a tournament long been dominated by the likes of England and New Zealand -- the former, in particular, investing large sums of money in their Under-20s program. New Zealand Rugby, meanwhile, operates under centralised system that controls everything from the All Blacks down, including the country's Super Rugby franchises, age-grade sides, sevens and women's rugby under the one banner. One organisation that sits outside New Zealand Rugby, but has the backing of the governing body, is the International Rugby Academy [IRANZ] run by former All Blacks lock Murray Mexted. IRANZ's track record is undeniable, with the likes of Israel Dagg, Aaron Cruden and Charlie Faumuina just some of its graduates, and the academy had 10 graduates named in the All Blacks squad for the recent British & Irish Lions series.  Mexted reveals to ESPN that he met members of the Australian Rugby Union high performance team, at the direction of board member John Eales, in the hope of replicating something similar to IRANZ in Australia. South Africa has already done so with its Investec Rugby Academy. But Australia opted against an academy in the IRANZ mould, with Mexted saying he believed the ARU was keen to use the formula but wasn't prepared to outsource it across the ditch. Mexted also told ESPN that he could understand why Australia would not want to be seen replicating a New Zealand-built program, particularly given Robbie Deans' mixed performance as Wallabies coach. "We're prepared to give and [the ARU] said, 'well, how will this work?',"Mexted tells ESPN. "And I said: 'Well, let's work it out, I'm open minded. We can have some sort of joint-venture, you can set up as a licensee and we'll bring all our intellectual property, which is how to run it and we'll run it and we'll grow your staff. Whatever. You tell me how you want to run it. "So anyway, bottom line was they didn't want to do it; that's it as far as I'm concerned ... what they've done is they've looked at what we're doing and tried to emulate that ... without the expertise and without knowing how to pull it together. There's two different things there." An ARU spokesperson confirmed to ESPN the governing body had discussed the prospect of setting up an IRANZ-style academy in Australia but that commercial arrangements didn't suit the Australian landscape of what the organisation required. Also, the ARU instead went down the path of looking at the entire coaching system which has already given birth to the National Coaching Advisory Panel and Rod Kafer's appointment. It may be in Australia that a centralised system akin to that run by New Zealand Rugby is not right in terms of player development, talent identification and, ultimately, seeing players contracted at the game's highest level; nor the involvement of Mexted's academy despite the high regard it is held in across the rugby world. Whitaker points to better collaboration between Australia's Super Rugby franchises in how they best identify emerging talent and then give the players the education, training and skill development they need to have the best possible opportunities to become Wallabies in the long run. Australian rugby has various pathways to the top -- be they club, school or sevens, across both male and female participation -- and there is a disconnect between the game's administrators and those at the coalface on grounds across Australia each weekend. With so many other facets under the high performance blanket, as illustrated by the diagram above, it's easy to see why the game is perhaps in the state it finds itself with grave concerns over what the player base might look like in the future. The ARU has taken a step with the creation of the National Advisory Coaching Panel, and there is a hope that more funds will flow down through high performance and grassroots rugby to deliver longer-term benefits at the elite levels. Given RugbyWA has challenged the ARU's decision to scrap the Western Force in the Supreme Court, however, the funds the governing body had hoped to redirect to grassroots and high performance avenues are likely on hold. And who knows what financial cost the ongoing Force saga may yet have on Australian rugby. The health of the Australian game, meanwhile, is deeply intertwined with the success of the Wallabies, and even one Bledisloe Cup Test win - perhaps as soon as the first match of the 2017 series, in Sydney - will inspire a badly needed sense of positivity. Kids and teenagers want to be involved with winners - it's that simple. Hence they will slowly be interested in playing rugby again if the Wallabies are winning, and, as they get older, they can filter into high performance environments. Suddenly, Australian rugby could in theory have shored up its foundations. "I think we have been recovering but, again, it's been in short bursts and hasn't had consistency," Kafer tells ESPN when asked if Australian rugby has struck rock bottom. "And the great example is we can go back and say only three years ago in 2014 the Waratahs win Super Rugby; the Wallabies, two years ago, finish second in the Rugby World Cup. Those two things are absolute results and great examples of the capacity that exists within the system. They're outcomes that were not expected at the time, which tells us there is this latent build-up of capacity [to deliver] within our system; it just needs to be channelled in a way that will consistency deliver results over time. "I think we've started to see recovery in certain areas of the game. I absolutely do believe we've bottomed out, I absolutely do believe the game will only improve from here. We're starting to see that redistribution in quality of rugby that's now flowing into club rugby, which is fantastic. We're starting to see people now invigorated, encouraged by what's happening in club rugby. Supporters are back at club rugby. This is the redistribution of talent and, I guess, entertainment. And that will force change above it of the next layers in the game."

|