|

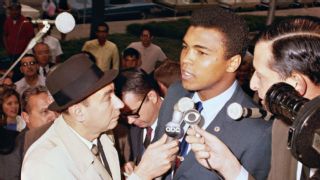

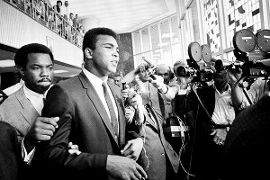

Nine words. That was all it took to launch Muhammad Ali along a path for which, over time, he would be both revered and resented in equal measure, and for which he ultimately would be identified almost as much as his achievements in the ring. The words spilled out on a February day in 1966, the day he learned he had been classified as eligible for the draft. Two years before, he had twice fared poorly in military mental aptitude tests, registering in the 16th percentile, and as a result was listed as unqualified for service. But with the Vietnam War rapidly escalating and the Army in need of many more men, standards were lowered and Ali was among those who were suddenly eligible. He heard the news from a local reporter, who pulled up in a television truck while Ali sat on the lawn in front of his Miami home. For the rest of the day, he endured question after question from media across the country, soliciting his views on the war, on Lyndon Johnson, on Vietnam. Finally, one journalist asked him how he felt about the Viet Cong, and that's when Ali, tired and frustrated by the inquisition, uttered those fateful nine words: "Man, I ain't got no quarrel with them Viet Cong." More than a year would pass before Ali actually received a draft notice and refused induction on the grounds that he claimed "to be exempt as a minister of the religion of Islam." That step resulted in his being stripped of the heavyweight title and forced into fistic exile for three years. But criticism was heaped on him the moment his Viet Cong remark hit the media.  Former light heavyweight champion Billy Conn called Ali "a disgrace to the boxing profession," and announced that he would "never go to another one of his fights." Congressman Frank Clark of Pennsylvania said the "heavyweight champion of the world turns my stomach." The influential sports columnist Red Smith excoriated Ali for "squealing over the possibility that the military may call him up." Eventually, of course, the tide turned against the war, and partly as a result, public opinion toward Ali mellowed and ultimately transformed completely, to the extent that his biographer, Thomas Hauser, warned against hagiography. Ali's "initial concern over being drafted wasn't religious or political," Hauser wrote in 2003. "It was that of a 24-year-old who thought he had put the draft behind him and then learned he was in danger of having his life turned upside down." As a potent sign of just how completely Ali's image eventually was rehabilitated, in November 2005, George W. Bush presented Ali with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor in the country. The Associated Press reported Veterans of Foreign Wars spokesperson Joe Davis as saying that two VFW members had complained to him about the award but that the organization itself had moved on. Similarly, when Sen. John McCain named his 2000 boxing reform act after the former heavyweight champion, he received, he said, "not a word of protest" from veterans. Throughout Ali's life, however, pockets of bitterness remained. Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Feller, for example, objected "very strongly" to the choice of Ali to throw out the ceremonial first pitch at the 2004 All-Star Game, saying, "A man who turned his back on his country shouldn't be honored that way; he declaimed." And an informal survey of Vietnam veterans by ESPN.com showed that, decades later, some wounds remained raw.  Most others, however, voiced opinions that were either more equivocal in their criticism, or even supportive of Ali's stance. Said Tillman Jeffrey, who served two tours in South Vietnam, mostly in helicopter gunships: "I still believe that he was wrong to have refused military service during the Vietnam War, but I have much more respect for him than I do those other Americans who hauled ass to Canada and then later got pardoned by President [Jimmy] Carter. Mr. Ali paid a very heavy price for refusing to serve, and I give him credit for standing up for his beliefs and taking his lumps like a man." McCain, a prisoner of war in Vietnam who was shot down and captured in late 1967 and wasn't released until Ali had been fighting again for three years, was as much a boxing fan then as now. Yet he said he disapproved of Ali's actions. "I didn't think it was the right thing to do," said McCain, who had met Ali on numerous occasions. "I wish that every American had served. But I respect what he did. He didn't dodge the draft, run to Canada or break the law. "I consider him and [Ali's wife] Lonnie to be friends. One time it came up. I said, 'Muhammad, I don't agree with what you did. But then, I've probably done a lot of things you don't agree with, either.'" Tim Baxter, a 58-year-old reference librarian in Florida, was in Vietnam when Ali was relieved of his title in 1967. He tried to recall what he thought about Ali's stance at the time, but figured that he "probably didn't think that much about it." Since then, he said, he had grown to "respect him for what he did. He could have gone to jail for this. If he'd just gone along to get along, he would never have been called."  Bill Perry, a paratrooper in Vietnam from 1967 to 1969, said that at the time of the controversy, he might have been "the only Caucasian from Philly who didn't worship Joe Frazier. I was a big fan of Sonny Liston, and after Ali sat him down in '64, it really turned me around. When we were drafted in 1966, our unit contained a lot of Puerto Ricans, black kids, hot-headed urban white kids. A lot of us liked Ali. When Ali beat Ernie Terrell [in February 1967, his penultimate bout before he was effectively banned from boxing], I was just finishing basic training. A lot of white kids in basic didn't like Ali, because they were told not to like Ali. When he said he wouldn't be inducted, we were just heading to jump school. At jump school, there were a whole lot of southern white boys. Defending Ali could lead to fist fights. He meant a lot to me. But I'm not like most soldiers. Most still hate him." "I have a great deal of admiration for him," said Jim Doyle, a rifleman who served in Vietnam from 1969 to 1970 and was wounded in action. "I wish I'd had the strength to do what he did. But I was 18, thinking only of my next beer and my next [girl]. I think Muhammad Ali did our country a favor. He stood up for what he believed in, took his licks and came back and astonished everybody to win the title again. I think he's a gentleman." History's ultimate judgment on Ali's actions is likely to reflect its ultimate judgment on the war, and on those who fought -- and those who chose not to fight -- in it. But the overall scorecard on his life will include many other considerations than his refusal to serve in Vietnam. Even without the war, Ali was always destined to be a polarizing and larger-than-life character, from his peerless skills (and occasional cruelty) inside the ring, to his brash demeanor outside of it, his membership in the Nation of Islam and, finally, his descent into the ravages of Parkinson's disease. "Every once in awhile, a transcendent figure comes along," McCain said. "Ali was one of them." Kieran Mulvaney covers boxing for HBO.

|