|

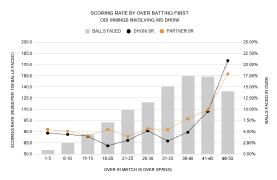

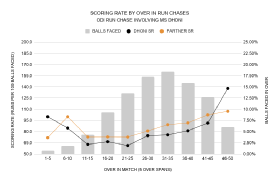

At some point in the next few months, it is very likely that MS Dhoni will retire from all forms of international cricket. For 15 years and over 500 internationals, he has been a world-class contributor, both behind and in front of the stumps. In the popular imagination, Dhoni is an end-of-innings gladiator who seemingly never got killed. This image does his game a disservice. The great Spain and Real Madrid manager Vicente del Bosque once observed of the midfielder Sergio Busquets: "If you watch the game, you do not see Busquets. But if you watch Busquets, you see the whole game." So it is with Dhoni and India's limited-overs game. In many games Dhoni was not really required to bat, and wicketkeepers in general tend to be noticed only when they miss something. However, especially in the last ten years of his career, if you watched the decisions Dhoni made, whether in the field or at the crease, you could draw a rich picture of the strengths and weaknesses of the Indian side. He was a relentlessly measured competitor. Like all world-class sportspersons, he often appeared to play within himself. He possessed immense power and a magnificent eye, but Dhoni became Dhoni, I suggest, because he decided sometime in the late 2000s that these were weapons to be deployed sparingly. They were means to a winning end, not the signature flourishes of an entertainer. What follows is a picture of Dhoni the limited-overs batsman. It is a role he mastered like few others ever have. Astonishingly, he did this while also being the Indian team's specialist wicketkeeper. The table above shows the 20 batsmen who have the best averages when batting at Nos. 5 to 7 in ODIs. This is an interestingly varied group. Some, like Inzamam-ul-Haq, Misbah-ul-Haq, Shivnarine Chanderpaul, AB de Villiers, Michael Hussey and Jonty Rhodes, are specialist batsmen. Others, like Andrew Symonds, Paul Collingwood and Hansie Cronje, were fifth bowlers. A few, like Umar Akmal and Rahul Dravid, kept wicket occasionally. Dhoni and Jos Buttler are the only two full-time wicketkeepers on the list. Partnership-level data available for ODI cricket does not provide the length of each partnership in terms of balls faced for all partnerships through the history of the format, but it is available for Dhoni's full career. The table below shows the top-averaging batsmen and the run production at each end while each of these players was at the wicket. What does it mean to have a batsman who is dismissed only once every 56 balls batting at Nos. 5 to 7 in the order? That reduces the chances of a collapse because the opposition will only really have one end from which to get wickets; this also frees up the other end. Dhoni's average batting partner is dismissed once ever 34 balls but scores at a run a ball, while Dhoni is dismissed every 56 balls and scores at 85 runs per hundred balls faced. The "other end" involves runs from the partnership that do not accrue to Dhoni. It includes extras in addition to the runs made by the batting partner. There have been suggestions that Dhoni has tended to score slower in recent years. Matters are slightly more complicated than that. The table below gives his record at Nos. 5 to 7 World Cup year to World Cup year. While there has certainly been the decline one would expect with age and the strain of a near decade of keeping wickets and batting in the middle order, Dhoni's approach has also been shaped by the kind of players available to India in other middle-order positions. His record in the period between the 2011 and 2015 World Cups has to be seen in light of the fact that India didn't have any real power-hitters in the lower-middle order in this period. Since the 2015 World Cup, they have found Kedar Jadhav, Hardik Pandya, and most recently, Rishabh Pant, all of whom answer to this description in some way. On the other hand, India have struggled to find (or preferred not to play) a specialist middle-order batsman at either four or six (with the exception of Ambati Rayudu). The team management's preference for bowling depth has worked in terms of results, but it has also meant that Dhoni and Virat Kohli have had to bat slightly more conservatively than they did a few years ago. Dhoni was used differently when India batted first than when they chased, and his approach differed. When India batted first, 64% of his batting occurred after the 30th over of the innings, 31% after the 40th, and 14% after the 45th. In chases Dhoni's presence shifted to the middle of the innings: 53% of his batting occurred after the 30th over, 19% after the 40th and only 6% after the 45th. Two-thirds of his batting in chases occurred in overs 21-40. In games where his turn to bat came earlier, his approach was to put away the big hits until the final ten overs.   Consider Dhoni's record batting first and batting second at positions 5, 6 or 7 in ODIs. The difference in approach is starkly evident. He was significantly less conservative when India batted first. The breakdown from World Cup to World Cup is revealing. It is true that Dhoni's approach in chases since 2016 has been significantly more conservative than it was in the 2012-15 period and similar to what it was in the 2008-11 period. It's worth noting that India have been a better chasing team in the periods when Dhoni has been more conservative (in matches where here has been required to bat). This adds to earlier evidence that individual players do not shape successful chases. A balanced team in which different types of players can play different types of innings shapes successful chases. The ability to accumulate runs steadily with certainty in the middle overs was Dhoni's most distinctive feature. As a batsman he was a calculating creature. The role he undertook in the Indian middle order (at Nos. 5 or 6, where he spent most of his time) was to deny the opposition a wicket from his end. If the batsman at the other end was a well set top-order player and the team's position was strong, then Dhoni would typically bide his time. More often, it was a fellow middle-order batsman, like Yuvraj Singh or Suresh Raina, and Dhoni would share the burden of scoring quickly. If the partner was a lower-order player like Ravindra Jadeja or Harbhajan Singh (these stands tended to come later in the innings), Dhoni would take more chances than his partner. Dhoni is remembered for things that are not really representative of his game and career. He has batted in 75 successful ODI chases for India. His typical approach is to drop anchor so that his partners are freed up to eat into the target. When Dhoni remained undefeated, India won 47 out of 49 games. In those 47 successful chases where he remained undefeated, he contributed, on average, 43 (47 balls) while the other end produced 50 for 1 in 49 balls. Forty of these 47 chases were completed before the final over. Overall, 134 of the 145 chases in which Dhoni batted (in all positions, not just five, six and seven) did not involve his presence in the final over of the chase. Dhoni came in for some criticism in the recent World Cup game against England. But the pattern of that game is representative of his general approach in chases. Over his career, Dhoni batted in 51 chases where he faced between one and 24 deliveries. These are games where the result was a foregone conclusion by the time Dhoni had his turn to bat, or games where he was dismissed cheaply. He batted in 94 chases where he faced 25 or more deliveries. India won 49, lost 43 and tied two of these games. Dhoni scored slower than his partners in 35 of those 49 chases won (he averaged about 54 at a strike rate of 88, while the batsmen at the other end collectively averaged 55 at 98). He also scored slower than his partners in 30 of the 43 failed chases (he averaged 41 at 72, but at the other end, it was 24 at 90). Dhoni's anchoring method worked when he could deny the opposition an advance at his end and the other end could take more chances. In games where the latter failed (as an average of 24 indicates), Dhoni's approach was to consolidate from his end further, and try to turn the game into a shorter, sharper contest late in the match. This failed most of the time. The World Cup game against England was an example of this type of match. The scoring-rate subsidy at the other end fell way short of what India needed. Dhoni tried to prolong the game, but it just didn't work. By contrast, in a different kind of, but equally difficult, chase against New Zealand in the semi-final, the subsidy did become available, mainly due to Jadeja's innings. A run-out interrupted Dhoni's decade-old formula. Of the 11 matches in which Dhoni was batting in the final over, India won seven, lost three and tied one. Four of the wins could be considered cases where the result was a formality (India required three, six, seven and seven in the final over in these games). One of the defeats could be considered an impossible situation, with 44 required from the final over. Of the remaining six games, India won three and lost three. Dhoni was not about taking the game to the final over. Rather, if a game went to the final over, it meant that the chase had gone badly and Dhoni's partners had not been able to make sufficient headway. While Dhoni could hit the ball with great power, his skill lay in keeping that power shut in a box with a sign on it that said "use only when absolutely necessary". Some players can't help but hit the ball hard whenever an opportunity presents itself. Dhoni was not like that, especially after he moved to the middle order and became the master anchor. As a quality, this is both less thrilling to the viewer and more difficult to master for a cricketer. Basic mastery of the limited-overs form is a prerequisite for this more advanced ability. Dhoni demonstrated this basic mastery early in his career, with a blistering 148 against Pakistan in Vishakhapatnam. His 183 not out in 145 balls against Sri Lanka in Jaipur later in 2005 marked him out as a player of rare quality. It came against Muttiah Muralitharan in his pomp. That day Sri Lanka posted 298 for 4 and India won easily. In the next game they posted 261 and lost again to Dhoni, who batted at No. 6 and returned with an undefeated 45 in 43 balls. In these early days Dhoni was one of the players in a flexible Indian middle order fashioned by Greg Chappell and led by Rahul Dravid. The shift to master anchor arguably came in Sri Lanka in 2008, where he made a couple of fighting 70s and mastered Ajantha Mendis, who had wreaked havoc in the Tests, mainly by playing him off the back foot. After that, he masterfully anchored the Indian middle order for a decade. It is perhaps a measure of his abilities that anything short of miracles from him are considered failure by his adoring public. But that's how it is with deities. They are created out of whole cloth by their devotees. It would be a tragedy if the cricketer and his cricket were lost to our memory, submerged under the fantasy Dhoni of public imagination. His was not a high-wire act. He did not seek to take the game to the last over. He sought something harder: to win with the minimum of fuss. He was so good that he succeeded far more often than he failed.

|