OTL: Where Is The Puck?

![]() HICAGO -- As he faked right, left and right again, Patrick Kane carried a half century of frustration on the end of his stick. The Chicago Blackhawks had been the Cubs of hockey. They hadn't won a Stanley Cup since John F. Kennedy was president. But now, as Kane skated toward the net, he had a chance to change that.

HICAGO -- As he faked right, left and right again, Patrick Kane carried a half century of frustration on the end of his stick. The Chicago Blackhawks had been the Cubs of hockey. They hadn't won a Stanley Cup since John F. Kennedy was president. But now, as Kane skated toward the net, he had a chance to change that.

He glided until he was almost parallel to the goal. It was a seemingly impossible angle. Yet Kane flicked the puck toward the net, where it slipped between goalie Michael Leighton's legs and vanished.

NHL playoffs

For comprehensive coverage of the NHL playoffs, check out the Cross Checks Blog featuring Scott Burnside and Pierre LeBrun. For Blackhawks coverage, visit ESPN Chicago.

This is where our mystery begins.

You would think finding a puck from the biggest hockey game of the year would be easy. That's what I thought when my editors asked me to find Kane's magic puck. With more than a dozen HD television cameras in the building that night, and some 20,000 eyewitnesses, many of whom were carrying their own cell phones and cameras, I figured I would just watch a few video clips, find the first person who touched the puck, ask him what he did with it and follow the trail. Easy stuff, right? Anyone who refused to talk or told a lie would be a suspect.

But what if you could never find the first person to touch the puck?

What if two people watching the same play tell you two different stories?

Or what if you come up with convincing visual evidence that seems to solve the mystery, but an NHL executive swears that you're wrong?

Then what would you do? Then whom would you believe?

The puck Kane shot past Leighton to give the Chicago Blackhawks their first Stanley Cup in 49 years is nothing more than a 6-ounce piece of rubber. But try telling that to Blackhawks fans. This is the puck that scored the most famous goal in Chicago sports history and only the 15th overtime Stanley Cup winner of all time. If the puck doesn't matter, why did the Hockey Hall of Fame ask for it immediately after the game? And why is a Chicago restaurant owner offering a $50,000 reward for anyone who comes forward with the puck?

The case of the missing puck is a story the NHL would like to go away. It's part "CSI," part "Slap Shot." It involves the FBI, a sergeant with the Chicago Police Department and the man who bought and blew up another famous piece of Chicago sports memorabilia. The stories are wacky. There's a policeman who swears the puck is at a pawn shop in Rockford, Ill., and an elderly lady who insists one of the Flyers has it -- all you have to do is watch the tape.

By the end, you'll wonder whether your eyes are playing tricks on you. You'll have more questions than answers. You'll be stunned to find out the Kane puck is hardly the only Stanley Cup winner that's missing. And you'll wonder who's telling the truth, who's lying and, perhaps most importantly, what they are trying to hide.

All over that 6-ounce piece of black rubber.

Federal Bureau of puck finders

It's a brisk midwinter afternoon in the Windy City, and I'm sitting in the sports-themed boardroom at Harry Caray's Restaurant. There are black-and-white prints of Wrigley Field on one wall and a framed Ryne Sandberg poster on another. Sitting across from me is a tall, lean, bespectacled man who looks more like an office IT manager than like Chicago's most famous sports memorabilia collector.

Grant DePorter has covered half the table with folders, notes, a pair of hockey pucks and seven high-resolution photos he was given by the FBI.

I had known for months that DePorter had offered a $50,000 reward to anyone who came forward with the puck, but I shrugged it off as nothing more than a publicity stunt. After all, this was the man who eight years earlier purchased the infamous Steve Bartman foul ball for $110,000 and a few months later blew it up with the goal of ending the Chicago Cubs' World Series curse. It was a genius stroke of PR. The detonation was broadcast live on multiple cable channels -- ESPN included -- and stories about it appeared in more than 4,000 newspapers worldwide.

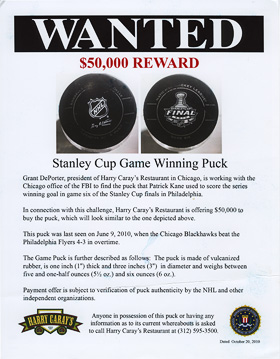

In 2005, when the White Sox won the World Series, DePorter paid $18,000 for the bat Orlando Palmeiro used in making the last out. This past winter, DePorter bought Sammy Sosa's corked bat for $16,000. So of course he wanted Kane's puck, especially given that the Hawks forward is a partner at the new Harry Caray's on Navy Pier, where DePorter is opening a Chicago sports museum. He even created a wanted poster, complete with exact puck specifications and the last date it was seen: June 9, 2010.

I grew up in the Chicago suburbs, own a red sweater with a giant Blackhawk on the front and was ecstatic when the Hawks won. But that's not why I want to find the puck. I'm fascinated by the story. I can't comprehend how something that seems so important could be swiped from an enclosed arena with everyone watching.

Before speaking with DePorter, I felt as if I needed to find out where the pucks used to score the other 14 Stanley Cup-winning overtime goals are today. What I discovered surprised me. Three of the past four teams to win the Cup in OT -- the Blackhawks last year, the Dallas Stars in 1999 and the Colorado Avalanche in 1996 -- have no idea what happened to their respective pucks. Only the New Jersey Devils in 2000 know where theirs is: Jason Arnott retrieved it and gave it to his father.

Puzzled, I reached out to the past five Stanley Cup champions to see whether they know what happened to their pucks. None of them does. A representative from the Carolina Hurricanes says in an email, "I wouldn't be surprised if one of the players grabbed it." A Pittsburgh Penguins official writes, "You might want to try contacting the referees or linesman -- although I doubt they would ever say if they had it."

Ahhh yes, the linesman. Another potential suspect. It was a Finnish linesman who claimed he accidentally pocketed the puck Sidney Crosby shot past Ryan Miller to win gold for Canada in the Vancouver Olympics. Stefan Fonselius said he didn't realize his error until he returned to Finland and the puck was still in his shirt pocket. He called the International Ice Hockey Federation and had the puck shipped back to Canada, where it is on display at the Hockey Hall of Fame.

I was baffled. Was this some sort of problem related to hockey? In baseball, the ball Doug Mientkiewicz caught to give the Boston Red Sox their first World Series title in 86 years almost ruined his life. After joking to a Boston columnist that he was going to keep the ball, Mientkiewicz became New England enemy No. 1, with his wife even receiving death threats.

"It made my life a living hell," Mientkiewicz said. "If I could go back, as soon as I heard the umpire call the final out, I would have dropped that ball on the ground and gotten away as fast as possible. It wasn't worth it."

Because of the Blackhawks Stanley Cup drought, the Kane puck is essentially hockey's equivalent of the Mientkiewicz ball. And not only is it missing but so are the pucks from the past five Stanley Cup winners? And three of the past four OT winners? And the Crosby puck was once missing, too? Phil Pritchard, curator for the Hockey Hall of Fame, where just one of the 15 overtime winners is on display, tried to help me understand.

"It's part of the hockey player's mentality," he said. "Nobody thinks about things like that. When that puck goes in, it's just bedlam. People are on the ice, guys are throwing their stuff all over the place, the trophy comes out and that little puck is lost in the scramble of everything.

"Would we love to have the Patrick Kane puck? Certainly. But I don't know if it's fair to say that the puck and those other pucks are missing. I don't know if they were ever had to be lost in the first place."

Back in the boardroom at Harry Caray's, DePorter tells me that in July he thought he had found the puck. A man from Philadelphia had heard about the $50,000 reward and told DePorter he had what the restaurant owner was looking for. The man had specific information about where he was sitting that night and his family's lifelong relationship with one of the employees at Wells Fargo Center. And he was paranoid about protecting that individual.

"He was so concerned about anonymity that I thought it might be legit," DePorter says.

DePorter had just completed the FBI's Citizens' Academy, where he learned about everything from fingerprints and forensics to evidence collection and fraud prevention. So he called Ross Rice, one of his contacts at the Chicago FBI office, to ask whether he could help authenticate that it was the actual puck.

Using a special digital microscope and the HD broadcast of the game, a pair of agents from the FBI's Regional Computer Forensics Laboratory worked on their own time to freeze the puck in the four-minute overtime, zoom in on it and take digital pictures that could then be compared with the puck that the Philadelphia man was selling. The work was similar to what the FBI's Art Crimes Team does to catch individuals who create counterfeit artwork and forged autographs.

"Every puck is going to wear differently," DePorter says. "It's going to get hit differently and have different marks, different DNA. It's like ballistics with a bullet. No two pucks are alike. If we could get a good image of this puck, we could compare it with any other puck people brought forward."

It took Rice and DePorter no more than five seconds to know the Philly puck wasn't the one.

"It wasn't even close," Rice said. "The two pucks didn't even have the same logos on them."

When The Chicago Tribune did a front-page story about the FBI's involvement in the puck hunt, DePorter's phone rang for weeks. Everyone had the answer. A cop in Rockford said he saw the puck for sale in a pawn shop under the title, "famous Patrick Kane hockey puck." An elderly woman told DePorter in a voice mail message that all he had to do was watch a replay of the game and he would see one of the Flyers "zipping down the ice, reaching into the net, taking the puck and skating away. There was no question about it," she said. "A Flyer player took it." And then there was the guy who told DePorter the answer could be found in a calendar that was being sold at a Chicago-area drugstore.

Several people contacted DePorter and said they had video evidence showing linesman Steve Miller picking up the puck. But DePorter already was chasing that tip, thanks to a video posted on a Philadelphia sports blog, CrossingBroad.com. Kyle Scott, the blog's 27-year-old founder, had pieced together a series of video clips he said showed Miller picking up the puck.

"My first thought was [Chris] Pronger got it," Scott told me later. "As a Flyers fan, I wish he had. That would have been the ultimate. But after watching the video, I'm very confident Steve picked it up. To me, it's highly unlikely that it was anyone else."

DePorter agreed, saying he had even received a tip from a hockey insider that one of the officials was the culprit and would talk only if pushed.

"Has anyone bothered to talk to Steve Miller and ask if he has it?" DePorter said. "To me, he's the key. Steve Miller is the person that you have to find."

Puck thieves

Nick Boynton is your stereotypical NHL journeyman. He's a tell-it-like-it-is grinder who has spent 11 NHL seasons playing for six franchises. After being acquired in March 2010, he played in just seven regular-season games for the Blackhawks and three in the playoffs. Yet his name is right there on the side of the Cup next to those of Kane, Jonathan Toews and the rest of the 2010 Blackhawks.

Boynton was on the ice when Kane scored the Cup-winning goal, but he's dressing for the Philadelphia Flyers in the 2011 playoffs.

"It's a bit strange," Boynton said. "I have to be careful with what I say. It's not like I can run around here with my ring on."

Boynton had eight points in 41 games for the Hawks before they put him on waivers Feb. 25. The next day, the Flyers signed him. Before he left the United Center for the final time as a Hawk, a Blackhawks official joked, "When you get to Philadelphia, find that puck."

Boynton smiled, nodded and left. If only the Hawks knew what he was thinking.

"If they wanted me to find the puck, they sure as hell shouldn't have put me on waivers," Boynton said. "If I find it here, it's staying here. Simple as that."

In the hours and days after the Hawks won, Boynton said none of the players mentioned anything about the puck. It wasn't until a few weeks later that the buzz began that the puck was missing.

"And then it took on a life of its own," he said.

On this day, Boynton sits in a new locker room with new teammates and sweat pouring down his face. He has just finished a grueling practice in which coach Peter Laviolette had the team skate up-and-back sprints like Herb Brooks in "Miracle." When I mention the puck, Boynton smiles. As I ask him who he thinks has it, his grin widens.

"If I was a betting man, based on what happened in the other games that series, I'd imagine somebody over here has it," he says. "I think Prongs might have it. That's what I always heard. But I have no clue."

"Prongs," of course, is Philadelphia defenseman Chris Pronger, one of the most hated players in all of hockey. He is hated because he's good, because he plays like a punk and because he wins. Each of the past three teams that traded for him ended up in the Stanley Cup finals. And no team that has let him go made the playoffs the next season.

During the Cup finals last summer, Pronger nabbed the puck after Blackhawks victories in Game 1 and Game 2. Chicago's Ben Eager took exception after Game 2 and the two exchanged words, with Pronger flicking a Hawks rally towel Eager's way. When asked afterward what he did with the puck, Pronger told reporters, "It's in the garbage -- where it belongs."

The Tribune responded by creating an illustration of Pronger in a figure skating skirt on the front page of its sports section with the word, "Chrissy."

When the Blackhawks won Game 5 to send the series back to Philadelphia for Game 6, the puck ended up near Boynton.

"And all of a sudden, Eager comes racing over to make sure I didn't fire the puck down the ice," Boynton says. "If Prongs wanted to take the pucks from Games 1 and 2, Eager was going to keep that one."

So it shouldn't be a surprise, then, that when it comes to who took the most important puck of all, Pronger is an obvious suspect. Perhaps too obvious.

A careful review of the NBC television broadcast shows that Pronger wasn't on the ice when the game ended. He is shown on the Flyers' bench as the Blackhawks celebrate in front of him. Does it mean Pronger doesn't have the puck today? No. Does it mean he wasn't the first one to pick it up that night? Almost certainly.

Pronger explained as much when the Flyers returned to Chicago in February for their only game against the Hawks this year.

"I was a little disappointed at that point to skate all the way down there and get the puck," he said. "That might have been a little much. If I'm on the ice and it's right in front of me, that's a different story. I would think one of [the Blackhawks], maybe they would have grabbed it. Somebody should look at the video. Somebody's got to have it."

The copycats

Inside the Blackhawks' dressing room, Patrick Kane is spending a rare minute all by himself. No teammates, no media, no coaches, trainers or equipment personnel. Just Kane. I approach and ask about the puck.

Like Boynton, he smiles.

"At first I didn't even think about it," he says. "You win the Stanley Cup and the puck is the furthest thing from your mind. But then you hear about the reward and the FBI and everything else, and you start to think this is getting a little crazy.

"It's not something I think about all the time, but of course I'm curious. I want to see it come up. I don't want it hiding out in the weeds, in a ditch, in the river, in the woods or wherever it might be. I want to see it get in the right hands."

For Kane, the right hands would be those of Blackhawks chairman Rocky Wirtz. A few times since that night in Philadelphia, Kane has wondered whether he has held the puck in his own hands without even knowing it. He often is asked to autograph replica pucks from the 2010 Stanley Cup finals, including several pucks that are labeled "Game Six." It turns out the NHL produced 3,900 "Game Six" pucks to sell to the general public. They look exactly like the puck DePorter and everyone else is looking for.

"Every time I see a puck with that NHL logo and 'Game Six' on it, I wonder," Kane said. "Could that be it? But I doubt it. I think somebody has it, they've hidden it away and they're not telling us something. That's what I think."

Doug Allen, the CEO of Legendary Auctions, estimated the puck's value at between $10,000 and $20,000. He said he thought DePorter's reward of more than twice that much should be enough to bring any puck hoarder out of the weeds.

But it wasn't that simple. After all this time, it would seem almost impossible for someone to come forward. Especially given that there are potential legal ramifications, according to Roger Abrams, the Richardson Professor of Law at Northeastern University. Abrams testified in the case for the ownership squabble over Barry Bonds' 73rd home run ball. He said that, in this situation, the puck is a work tool supplied by the NHL to complete a task. Someone not authorized to take the puck could face theft charges -- especially if that person tried to sell it.

"If you take a Picasso home and put it in your basement just to look at, you're still liable criminally," Abrams said. "But it probably only comes to light when someone tries to sell it. That's when there would be a problem -- especially because there are quite a few people in Chicago who would like to have that puck."

With Mientkiewicz, the Red Sox used a similar "work tool" argument to try to persuade the first baseman to return the ball. But in baseball, the player who catches the final out typically decides what to do with the ball. Some players have given it to the team, others have kept it. Mientkiewicz said the players' association encouraged him to keep the ball, but the stress of doing so became too much. He and the Red Sox eventually agreed that he would turn the ball over to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Chicago's reaction to the missing puck is a far cry from what Mientkiewicz went through in Boston. The average fan doesn't even know the puck is missing. Yet Mientkiewicz warns me to be cautious with my words.

"I don't know if the people in the media always understand the power they have," he said. "You can do more damage than you realize."

Meeting Steve Miller

I'm at an early-March game between the Blackhawks and the Calgary Flames. Marian Hossa scores a late goal to help Chicago to its fifth straight win, but I have other things on my mind.

Linesman Steve Miller is in the United Center tonight, and I'm going to do everything I can to ask him about the puck before he leaves. As the final seconds of the third period tick away, I stand outside the officials locker room and wait for Miller. That's when an off-duty Chicago police officer orders me to move.

"You can't stand here," he tells me.

I shuffle around the corner and anxiously wait for the locker room door to open. Some 40 minutes later, Miller emerges. He is taller than I imagined. His hair is still wet from the shower. He's wearing dark slacks, a white dress shirt and a black winter coat. He has broad shoulders. A muscular chest. I introduce myself, tell Miller about my quest to find the puck and ask, "What happened that night?"

He doesn't get angry. He doesn't yell. He doesn't even look away. Like a politician fresh out of PR school, he looks me straight in the eye and unflappably explains.

"I have no clue. I never touched the puck. I never touched it," he says. "For sure. I've been asked that question a few times, but I never touched the puck. The reason I went down by the net was to look for the puck."

Miller then reminds me how unusual of a goal it was and how hardly anyone in the building -- himself included -- knew what happened that night. The red lamp never lit. And the announcers on the NBC and CBC broadcasts struggled to describe what happened after the puck appeared to vanish under a piece of white plastic at the bottom of the net. Had the Hawks just won the Stanley Cup? Was the puck stuck in Leighton's padding? No one knew.

Since the goal happened at Miller's end, he went into the net to find the puck. He never did.

"When we went in the [officials] room," Miller says. "That was the first time I ever seen the puck in the net."

Miller, 38, has been an NHL linesman for 10 years. He has officiated more than 500 regular-season games and 50 playoff games. The Canadian-born Miller is one of the league's top linesmen. He worked the 2009 and 2010 Stanley Cup finals.

Rolling his black suitcase behind him on this night, Miller is ready to leave the United Center and head to his hotel. But before he departs, I toss him a softball question, just to see how he responds.

"And you've been asked this before?" I say, repeating something he had said earlier. Miller answers the question and, looking me straight in the eyes, defends himself one last time.

"I've been asked that a few times," he says. "I wish I could say … I wish I could say I had it or I wish could say that I touched it. But I never touched the thing."

With that, he was gone. As I head in the other direction, I have no idea what to think. In some ways, his answers seemed rehearsed, especially as he stated over and over that he never touched it, never saw it. But then again, I thought, if this is the truth, what's he supposed to say? How's he supposed to act?

My gut tells me that for Miller, lying is too big of a risk. There's too much at stake for a top linesman to snag a historic hockey puck, then fib about it -- especially when he knew the entire hockey world was watching.

Right?

The next day, searching for answers, I look at every photo and video I can find of Miller and Leighton around the net. That's when I find it -- an Associated Press photograph that shows Miller, linesman No. 89, bending down on one knee in the goal next to Leighton and the puck. In the photo, the puck is sitting beside Leighton's right skate and Miller appears to be looking right at it. While his right arm is pointed toward the puck, his right hand, just inches above the puck, appears to be opening.

Never saw it? Never touched it? Busted, I think. I print an 8-inch by 10-inch copy of the picture and go back to the United Center the next night hoping that Miller will still be in town working the next Blackhawks game.

He is.

So I wait, again, outside the officials' locker room, this time armed with the evidence. When Miller emerges, he recognizes me and says hello. I tell him I have another question. But before I can ask it, Miller informs me that he has told league officials I had been waiting for him outside the locker room two nights earlier.

I don't know how he wants me to respond to that. And I don't care. I tell him I already had informed the league I was working on this story, so there was nothing to worry about.

Then I begin: "Steve, the other night after we talked I went home and found this photo …"

Miller glances down at the picture in my hand.

"Yeah?" he says. "Where's the puck at?

"Right there," I tell him, pointing to the black circle.

"Is that the puck?" he asks.

"That's pretty clearly the puck," I say.

Miller pauses. He looks closer.

"I never touched the puck," he says. "It shows my hand right there. If that is the puck. I guess it is. I never touched it, though."

I ask who is supposed to retrieve the puck from the net after a play like that. He tells me there is no protocol. And then, like a well-trained defense lawyer, he attacks the evidence the prosecution has just set before him.

"Sure from that picture there," he begins. "I mean … who knows what kind of angle? Who knows? I never did touch the puck, though. So … I never touched it."

It wasn't that difficult of an argument to make, I suppose, since Miller's hand was not actually making contact with the puck. But his head seemed to be looking right at it. Would he still tell me he never saw it, too?

"Nope," he says. "I don't remember seeing it."

"But Steve," I say. "It's pretty clearly right there."

"It's pretty clearly there, yeah, but where's his pad?" Miller says, pointing to Miller's right leg. "I never touched the puck."

I shift gears.

"If not you, then who has it?" I ask. "Who should I talk to?"

"I honestly don't have a clue," he tells me. "Honestly, I don't know where it would be. It's a mystery. Who knows? [Leighton] could have shot it away right away. And I may not have even seen it. It looks like I'm looking down there."

"Steve," I say, "It looks like you're looking right at it."

"From the picture it does, yeah. But I can honestly say that I didn't … when we came off the ice there was all the director of officials and all that kind of stuff, and they asked where the puck was. They wanted to know right there. The Hockey Hall of Fame wanted it."

Miller tells me that this picture had appeared in "all the newspapers," including in his hometown, and that friends and family had asked him whether he had the puck. But this didn't make sense. If Miller had seen the photo previously and people had asked him about it, then why, two minutes earlier, did he not know where the puck was in the same picture?

Miller continues to make his point, this time using the presence of a young blond woman standing across the United Center hallway to do so.

"You can see a picture," he says. "If you're out one night and you've got a girl like this beside you and your wife sees it, she's going to ask, 'What are you doing?' You know what I mean? It's the same picture as that. You can see [the puck] right there. But I didn't see it. I didn't see the puck. I didn't touch the puck. That picture doesn't tell the whole story. Who knows, maybe Leighton shot the puck away right there. We don't know what happened after that."

Before he leaves, Miller tells me that he would be telling the NHL public relations director again that I had been waiting for him. Then he makes one last closing remark.

"Honestly Wayne, I never touched it," he says. "And if I did, I would have handed it over right after the game if I had it."

Miller's denial means one thing: I have to meet with the only other person who was there with Miller to know what happened: Philadelphia goalie Michael Leighton. Maybe he saw Miller pick up the puck.

The witness

The professional athletes who come to Glens Falls, N.Y., are typically at a crossroads in their career. Either they're on their way to the big time or have hit some sort of a speed bump and are trying to get back. Michael Leighton is the latter. Less than a year ago, he was a starting goalie in the Stanley Cup finals. On this day, he's the starting goalie for the Adirondack Phantoms.

A back injury is mostly to blame, but that doesn't make things any easier. He's living in an apartment; there's snow up to his knees; and his wife and two kids are back in Canada. They keep in touch through Skype. He has more important things to worry about than what happened to the puck that got past him for the one goal he would give anything to have back.

I ask anyway, as we sit on a wooden bench in the bowels of the Glens Falls Civic Center. What does he remember about the puck? He begins with the four words that are now sounding like a broken record in my head.

"I have no clue," he says. "I remember lifting up the net and kicking the puck into the corner. Then I remember somebody going to pick it up. I thought it was one of their players. But I'm not sure."

Finally, a breakthrough. Leighton is the first person I've found who admits to touching the puck after Kane's goal. I try to hide my enthusiasm. I fail. My mind races. Maybe his pads were shielding the puck from Miller and the linesman in fact never saw it. If Leighton kicked the puck into the corner, then I need to watch all the footage and start studying the corner. I ask Leighton to tell me more.

"When [Kane] scored, I think we were the only ones who knew it actually went in the net," he says. "And my first thought was, 'How am I going to get this puck out of the net as soon as possible so nobody knows it's a goal?' I knew there was no way. I knew they were going upstairs [for a replay]. But I waited and waited and then I lifted up the net and kicked the puck away to make it seem like it was somewhere other than in the net."

Then Leighton drags his right foot along the concrete floor and shows me exactly how he kicked the puck. I ask him to tell me again what happened after that.

"I remember somebody picking it up," he said. "Either the linesman or one of their players."

I pull out the picture that I had shown to Miller and ask Leighton whether it was possible that Miller might not have seen the puck from the angle at which he was kneeling.

"Possibly," he says. "That's right before I kicked it."

When I get back to Chicago, I call DePorter and update him on the story. I tell him what Leighton said and suggest that Miller might not be guilty after all. DePorter struggles to believe it. He tells me there is somebody else I need to talk to: Sgt. Sean Rice with the Chicago Police Department.

Irrefutable evidence?

Sean Rice's family, friends and co-workers all think he's crazy. Whatever happened that night at the Wells Fargo Center in Philadelphia, he needs to let it go. But he can't.

Rice was there for Game 6, sitting in Section 120, Row 13, Seat 5 -- 13 rows up on the opposite end of the arena from where Kane scored the winner. Seconds after the goal, Rice pulled out his video camera and started recording the celebration. He had no idea that, in the background, he was also capturing something just as important.

When Rice heard the Kane puck had gone missing, he broke down his video, frame by frame, to see whether he could provide any information about what had happened. The footage is 26 seconds long. It's wobbly and a little difficult to follow. But broken down into individual images, the picture becomes clearer.

In the video, after Miller fails to find the puck in the net, a tiny black dot sits a few feet outside the crease. Miller is then seen bending over, with his hand reaching down toward the ice. When Miller stands upright, the black dot is gone.

An AP photograph taken at the same time shows that the black dot appears to be the puck.

"The video and images speak for themselves," Sean Rice said. "There's no debating it. When you're caught, you're caught. This would be an easy one for the jury. There's not much to debate here."

Another video clip shot from the other end of the arena and used in the Crossing Broad video seems to support Rice's claim. Freezing that video at the 44- and 45-second mark also appears to show Miller bending over and picking up a black object.

Rice never put his video on YouTube. He didn't share it with anyone. Instead, knowing of DePorter's quest to find the puck, he phoned Harry Caray's to tell DePorter what he had. DePorter then sent the clip to Ross Rice (no relation to Sean) at the FBI and asked whether they could use their digital microscope to zoom in on the footage and determine definitively whether Steve Miller picked up the puck.

What they found might surprise you. Or it might not.

"In our mind, we are 100 percent certain the linesman picked up the puck," Ross Rice said. "What he did with it afterwards, we don't know."

Sitting at a cheeseburger joint on Chicago's West Side, Sean Rice turns animated when I tell him what Miller told me about never touching or seeing the puck.

"It's frustrating," he says. "As an official, you would think credibility is everything. But this is becoming just one big joke. All at the expense of the Blackhawks."

Seeing is believing -- or is it?

With the season winding down a couple of weeks back and my deadline quickly approaching, I knew there wouldn't be time to find Miller again to show him the Sean Rice video. And even if there was time, I was pretty sure I knew exactly what he would say. Never touched it. Never saw it. Don't believe what you see.

So I do what any reporter would do -- I call his boss. Terry Gregson, the NHL's senior vice president and director of officiating, spent 25 years as an NHL referee, officiating more than 1,400 regular-season games and 158 Stanley Cup playoff games. He's been in charge of the NHL's officials since September 2009.

Gregson answers the phone in his New York office and, before I can finish telling him who I am, what I'm working on and what I want, he interrupts me.

"I don't know where it is," he says. "I believe you know more than I do."

He continues, but seems to want to get off the phone as quickly as possible.

"Steve Miller, people have accused him," he begins. "I have no clue where it is. I'm sorry, but I can't help you. We never had it. As soon as the game was over, as soon as the officials came off the ice, I went into their dressing room to ask about the puck. And they told me they didn't have it. They never had it. We don't know where it is."

I tell Gregson that there is pretty convincing photo and video evidence that Miller picked up the puck that night. He reiterates the company line.

"All I can say is don't believe everything you see," Gregson tells me. "I would stake my reputation on Steve Miller."

With that, the conversation ends. And again, I'm stumped. If he did pick up the puck, why would he say he never saw the puck and never touched it when it appears, on video and in photos, that he did?

Why would Gregson defend Miller so strongly, even in the face of mounting evidence? Was there some sort of explanation?

Could Steve Miller actually be telling the truth?

If Miller, in fact, never picked up the puck, who did? The only other person in the frame when the puck is around the net is Leighton. But at no point does he bend over. And what would Leighton want with a puck from arguably the goal he'd most like to forget? To give it to Pronger?

Is it somehow possible that the black dot on the ice isn't the puck and Leighton actually did kick it into the corner, in a way that can't be identified on camera? I checked every photo and video I had, and the puck never appears to go in the corner. I still can't help wondering whether I missed something. But if I had, then what about the FBI, which is "100-percent certain" that Miller picked it up?

These are the questions that keep me awake at night. Along with the most important one of all -- the original question my editors sent me out to answer: Where is the puck now?

I have no idea. Maybe it's buried in a box in someone's basement. Maybe it's framed as the centerpiece on someone's fireplace mantel. Maybe it got scooped up that night and ended up in a box with other used pucks and is now used in some rec league in Manitoba.

Or maybe we'll just never know. And the case of the missing puck will always come down to one basic question:

Whom do you believe?

Wayne Drehs is a senior writer for ESPN.com. He can be reached at wayne.drehs@espn.com. You can find his story archive here. Follow him on Twitter: @espnWD.

Follow ESPN_Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader.

Join the conversation about "Where Is The Puck?"