ESPN.com

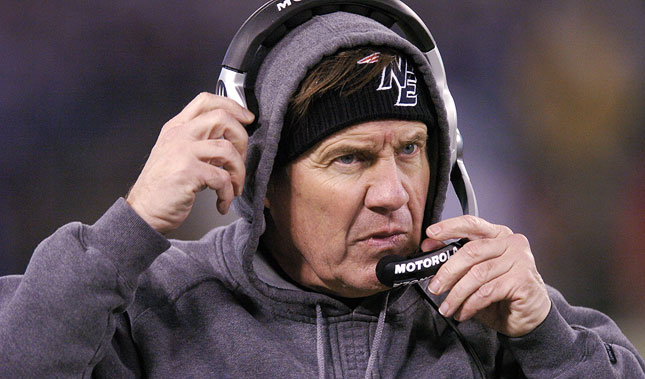

When Belichick is taking those lonely walks up and down the sideline, his head bowed as if in prayer, you can bet it's Ernie Adams yapping away in Belichick's ear. Some call him the smartest man they've ever met. A longtime NFL watcher compares him to "Q," James Bond's master of espionage and gadgetry. Author David Halberstam called him "Belichick's Belichick." No other team has anyone like him on its payroll. And yet, save for football insiders, he is virtually unknown. In an era of media oversaturation, there is exactly one more picture of Bigfoot on The Associated Press photo wire (two) than there is of Adams (one). And it's of the back of his head.

So here, in the ballroom of the Phoenix Convention Center, just six days before New England will attempt to complete a perfect season that Adams played a significant role in creating, I want to know what the almost-perfect Patriots think about their secret weapon: a guy with thick glasses and the sartorial sensibility of Mister Rogers; a guy who lived with his mother until she died three years ago.

Who, exactly, is Ernie Adams?

"I don't know what his job title is," linebacker Adalius Thomas says. "I didn't even know his last name was Adams."

"Ernie is a bit of a mystery to all of us," offensive tackle Matt Light says. "I'm not sure what Ernie does, but I'm sure whatever it is, he's good at it."

Finally, I approach receiver Wes Welker. "I'm writing a story about Ernie Adams," I tell him.

"Who?" he says.

"The guy who's always with Belichick who doesn't ever really talk."

"Oh," he says, recognition washing over his face. "Ernie."

He thinks for a second. "He's got to be a genius," he says, "because he looks like one."

THE FRIENDSHIP

This is why God created best friends. Inside a cavernous church, Ernie Adams sat through his mother's funeral, the saddest day of a man's life, and by his side, where he'd been for years, was Bill Belichick. Sept. 25, 2004 was a beautiful New England day, a Saturday morning during the Patriots' bye week. In the tree-lined suburb of Brookline, Mass., a small crowd had gathered in the Gothic Revival Episcopal Church on the corner of St. Paul Street and Aspinwall Avenue. The stone bell tower rose cold and medieval against the fall blue sky.

The mourners had come to say goodbye to Helen Adams, a woman who loved education and adored her son even more. Ernie and Helen lived together, like something out of a Victorian novel, one friend said, with much doting and an occasional trip to the old continent. At the end, Ernie took care of his mother. In the crowd were friends from childhood, high school and college. One of them was the headmaster of Dexter School, where Ernie went to elementary and junior high. "I was struck by the loyalty of Belichick to Ernie," Bill Phinney says.

That bond is the cornerstone of the Patriots' dynasty. In many ways, the traits we associate with Belichick and the Patriots are traits commonly ascribed to Adams. The humble pie? Classic Ernie, frequently described as having no ego. The rumpled hoodie? Again, classmates remember, classic Ernie. Together, Adams and Belichick have created the transcendently successful franchise they dreamed of creating back in high school.

"It's really the story of a friendship," says Michael Carlisle, a successful literary agent who was Adams' high school roommate at Andover.

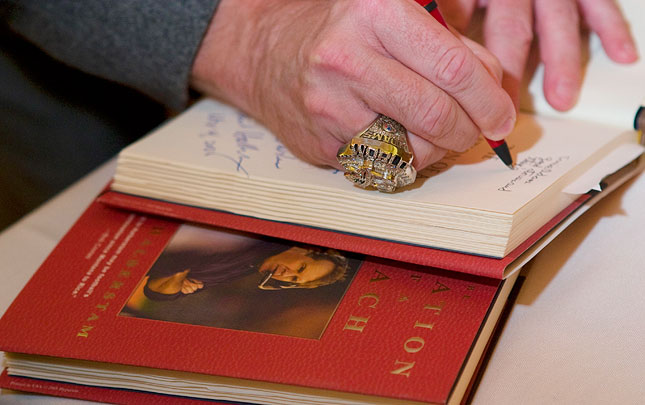

Adams and Belichick met in 1970. Adams had been at Phillips Academy in Andover, an elite New England boarding school, for three years. In that time, he'd become a campus legend, famous for his quirky attire and habits. He wore high-top cleats and old-fashioned clothes, looked and talked like something from the 1940s. His three obsessions were Latin, naval history and, strangely, football. So he consumed books, mostly obscure titles, with a scholar's thirst. One he ran across was called "Football Scouting Methods" by a Navy assistant coach named Steve Belichick. As Halberstam details in his biography of Belichick, "Education of a Coach," only about 400 people bought the book: professional scouts and 14-year-old Ernie Adams. So, imagine Adams' surprise when, as his senior year was beginning, he walked out onto the football field and encountered a young man with "Belichick" written on tape across the front of his helmet.

Bill Belichick had recently enrolled at Andover for a post-grad year, hoping to raise his grades and test scores so he could get into a good college. A few questions confirmed Adams' suspicions. Are you from Annapolis? Are you related to Steve? Yes and yes. Belichick thought it was strange that a kid would have read his dad's book. Adams recognized something familiar in Belichick. He recognized himself. "He actually was pretty good in his judgment of people," says Hale Sturges, the professor in charge of South Adams Hall, where Adams lived.

They've been like brothers ever since, spending hours after practice breaking down film, diagramming famous plays of Vince Lombardi, Adams' idol. They snuck into Boston College practices to "scout." Together, they played on the undefeated Andover team, the first time the two men tasted perfection.

Adams got his first big break after college, starting as an administrative assistant with the Patriots in 1975 and landing an actual assistant coach's job with the New York Giants in 1979. Immediately, he told Giants coach Ray Perkins there was another young coach he should hire. Something in Adams' voice made Perkins listen. Adams was already a man who demanded trust; Perkins calls Adams' opinion on football "gospel." So, Perkins picked up his phone and set up a meeting. After three hours in a hotel room, he had his new special teams coach: Bill Belichick. "Ernie's recommendation opened a big door for Belichick," Perkins says.

Belichick's career took off. He had something inside him that Adams did not -- maybe ego, maybe a hunger for greatness and glory. But wherever Belichick went, Adams soon followed, his arrival buried in the agate pages or reporters' midweek notebooks, his job title sufficiently vague to inspire more questions than answers. But there he was, in the background, breaking down film, offering Belichick unfettered honesty. When the Browns hired him, Halberstam wrote, it was Adams who cautioned Belichick to read the description of owner Art Modell in Paul Brown's book. "Don't say you weren't warned," Adams said. "It's all spelled out."

Stop after stop, no one was really sure how Adams spent his days, only that he had Belichick's ear. "When they talk," Carlisle says, "Bill knows that Ernie goes back to 1970. There is no bulls--- between them."

THE JOB

This brings us to the million-dollar question: Behind the quirks and the strange attire and the random attacks of sleep, what is it that Ernie Adams, you know, does? Years ago, Modell offered $10,000 to anyone who could tell him. No one could. A few years back, during a team film session, the Patriots players put up a slide of Adams. The caption read: "What does this man do?" Everyone cracked up. But no one knew.

In the broadest definition, Adams seems to be a man who loves to be in the background of greatness. Many things have his fingerprints on them, such as the game plan that engineered the upset of the Rams in Super Bowl XXXVI. Yes, Adams and Belichick figured out how to neutralize Marshall Faulk on the plane ride to New Orleans. Adams is involved in a lot of surprising things; he's a kind of "Forrest Gump" of sporting success. Like, say, the best-selling book "Friday Night Lights," which documented high school football, and later became a movie and a television show. That's right. "I'm indebted to him because he really turned me on to Odessa, Texas," says author Buzz Bissinger, who went to Andover with Adams and Belichick.

Adams' contributions to the Patriots begin with film. Hours and hours of film, often in his darkened office. He has been doing this for years, first at Northwestern in the early 1970s, where he convinced coaches to let him go from student-manager to scout. "He was a prodigy," says Rick Venturi, an assistant on that Wildcats team.

By now, after years of evolution, Adams sees film differently. Not just as random actions, but a genealogy of the game of football. When a defender moves, he recalls watching or having read about the first time a defender moved like that, even if it was 50 years ago, and he knows why, which tells him how to counteract the move. He has a photographic memory. Perkins tells a story of Adams' memorizing the Giants' thick playbook. In one night.

So, every week, the Patriots get the kind of analysis that only high-powered hedge funds or, say, NASA can afford. "Nine times out of 10," Bissinger says, "Ernie sees something nobody else sees."

That memory and those hours of studying film make him an unparalleled resource for assistant coaches. Want to know what a team does, and why? Want to know what a team has done on third-and-short in the red zone in the past 10 years on the road? Ask Adams. He'll know.

Adams' reach doesn't stop there. The Patriots are famous for compartmentalizing: The scouts can't watch practice, the game planners don't know who they are going to draft, and so on. But Adams is into everything. During the draft, according to Michael Holley's "Patriot Reign," he's in charge of running through the team's value chart, figuring out who will best fit their needs. This is the perfect assignment for someone who spent several years in the late 1980s as an analyst and trader on Wall Street and, as an investor, is known for spotting profitable trends shockingly early.

Pats owner Robert Kraft, a successful businessman in his own right, discusses economics with Adams. Belichick jokes that he wishes Adams would manage his portfolio. And the roots of the Patriots' insistence on value, and not letting emotion get in the way of sound investments, sound like they might have sprung from the mind of one Ernie Adams. "Warren Buffett and Ernie are actually somewhat similar," Carlisle says. "I have met Warren Buffet. Warren is one of these people who is phenomenally rigorous in his analysis. If there was someone you might associate with Ernie, it is someone who is [also] slightly asocial."

Adams' official title is director of football research, and he does a lot of that, too, trolling the world for things that might offer the slightest advantage. A year or two ago, an Andover teammate ran across an obscure out-of-print book on nonlinear mathematics. He thought Adams might find a use for it, so he mailed it to him. Adams had already read it. Or there's Rutgers statistics professor Harold Sackrowitz, who got a call from Adams a few years back. Adams wanted to talk about some research Sackrowitz had just completed, dealing with how teams try two-point conversions far too often. Adams sent the professor the Patriots' when-to-go-for-two chart, and asked Sackrowitz to tear it apart. Of the 32 NFL teams, the statistician told the New York Times, only the Patriots called.

Here's another example: The academic paper of a Berkeley researcher, referenced in the same Times story, dealt with how teams punt on fourth down far too often. That paper ended up on Belichick's desk. Now, how do you imagine it got there?

On game day, Adams wears a headset in the press box, a direct line to Belichick. Adams advises Belichick on which plays to challenge, and charts trends. "The one thing the Patriots do better than anyone else is they adjust and make halftime adjustments," Sturges says. "Ernie Adams is the guy who does that."

Are there other game-day duties? While it is commonly accepted that most teams try to steal signals, and New England was actually caught in the well-publicized Spygate incident, one former Patriots insider said a videotape of signals wouldn't help the other 31 teams nearly as much because they wouldn't have Ernie Adams there to quickly analyze and process the information.

And, if any of this happens to be true, Adams' love of military history suggests he might see deciphering signals as just part of winning a battle. Friends say he is wildly competitive. "Behind the exterior of a guy who lived with his mother," Bissinger says, "he is a guy who is really savage about winning games."

THE MAN

But that doesn't totally answer the question, does it? Knowing what Adams does cannot explain where a mind like his comes from. Did it come fully formed from the womb, or was it created slowly? Certainly, at an early age, he searched for strong male influences. His father, who wasn't around much, was a career Navy officer. As he grew up, Adams studied naval history and tactics almost as much as he studied football. But from the beginning, there was something strange about him. As a high school teammate describes him: "Odd, in a good sense."

Dexter athletic director George Dalrymple hasn't forgotten the first time he ever saw Adams. The boy was in third grade and Dalrymple walked into the locker room to find, gathered in total silence, a group of first and second graders. In the center stood Ernie, reading them "Winnie the Pooh." That year, Adams began playing football. He adored the game, latching on to Coach Dal. A quote from Vince Lombardi in the coach's office would stay with Adams, inspiring a lifelong love affair. Football is only two things. Blocking and tackling. Even then, Adams showed hints of what was to come. His favorite play, installed at his request, was a goal-line, tackle-eligible play. Adams was the decoy. The play almost always worked. He didn't mind not getting the credit. "It was part of winning," Dalrymple says. "He liked to win."

While in sixth and seventh grades, Adams read Lombardi's book "Run to Daylight" about 20 times. His obsessive personality drew him further into the web of this game, one with X's and O's he could control, men he could make appear whenever he wanted. It was simple, something missing in the 1960s. The campus and nearby Harvard were exploding in anger over the Vietnam War. Everything was turned upside down. "He was very old-fashioned," Bissinger says. "He was sort of the Lombardi era. Something about him was out of the 1940s. He was just different. He had no knowledge of rock 'n' roll or sex or drugs. The [high] school was rampant with it. Everyone was stoned. Everyone was drinking. And there was Ernie in his high-top cleats talking football with the head coach."

Still, the environment at Andover encouraged his searching. He has been lucky that way. His entire educational life, he has lived and studied in incubators of creativity. Dexter educated John F. Kennedy and Washington Post legend Ben Bradlee. Andover is famous for its students, too. Dr. Spock went there. So did Samuel Morse and Duncan Sheik, as did both Presidents Bush, and Jeb Bush, who graduated with Adams. (Scooter Libby also went to school with Adams.) Humphrey Bogart went to Andover. Jack Lemmon, too. Bart Giamatti and Bill Veeck. Senators, ambassadors, Medal of Honor winners, Nobel laureates. Andover is a place that encourages its students to dream of greatness and achieve it. Only, they didn't quite know what to do with a kid who wanted to be great at … football. Teachers wrote worried letters to his mother. So did Sturges, who thought Adams had the potential to do anything he desired. "I wanted him to try different things and move out of his little cubicle-type thinking," he says. "It never really happened."

But Adams took his task seriously, devoting his senior project to the study of the Andover football team's tendencies. "We throw around too many words," Bissinger says. "We throw around 'brilliant' too much and 'genius' too much, but I really believe this: Ernie was a scholar at football. And he was a scholar at football at Andover. Kids were scholars of physics. Kids were scholars of Latin. Kids were scholars of math. And here was this sweet, goofy guy who was a scholar of football."

THE MIND

That is how this mind was molded, but still, it does not take us into the mind itself. Only Ernie Adams can do that, and he won't. You might have noticed Adams isn't quoted here. He's rarely quoted anywhere or, for that matter, seen anywhere. Especially this week, when he's searching for the tiniest advantage. "Look for him at Super Bowl parties," Sturges told me. "Look for him. And I bet you won't find him. He is going to spend every minute out there preparing for this football game. It means everything to him."

Adams is private. Dalrymple even said Adams kept his mom's obituary out of the Boston papers. So you can never really tell what is going on in his head. But I did get Carlisle to call Adams on Monday and ask for his five favorite books, hoping to get a window into the places a man like him goes for inspiration. Here is the list:

- "The Best and the Brightest," by David Halberstam

- "The Money Masters of Our Time," by John Train

- Robert Caro's three-volume biography of Lyndon B. Johnson

- Robert Massie's biography of Peter the Great

- William Manchester's two-part biography of Winston Churchill

What does this list say about someone who won't say anything about himself?

Obviously, he admires great men. His reading list includes Warren Buffett, featured in Train's cult classic on investing, presidents, czars, prime ministers. Adams seems to enjoy the tiny spaces inside great lives, seeing them from behind the curtain. Could that be behind his close connection with Belichick?

Adams also seems to enjoy not only watching greatness work, but also seeing it fail. Carlisle thinks the central message of Halberstam's Vietnam classic appeals to Adams: that people incredibly well-educated and well-intentioned could be so flat-out wrong about something. It's a helpful notion to keep in mind about the conventional-wisdom-obsessed world of football, where pedigree and tradition dictate many overly conservative decisions. Indeed, when Adams agreed to participate in Halberstam's Belichick book, he did so with this caveat: For every two questions the journalist got to ask Adams about football, Adams got to ask one back about Vietnam. Did that trait allow Adams to make sure the mistakes of Belichick in Cleveland were not repeated? Maybe.One theory is Adams enjoys these books because, as has happened in his daily life, it gives him a chance to be next to greatness. Carlisle has a different take: Adams isn't drawn to the subjects so much as the authors, men who devoted their lives to scholarship. All of his favorite writers studied power in various forms, from Caro's investigations into the acquiring of power to Manchester's studies of those who wielded it: JFK, Rockefeller, MacArthur, Churchill, Magellan.

Remember that if you happen to catch a glimpse of Ernie Adams on Sunday, wearing a headset in the press box, in the ear of a coaching legend. Think about the miracles of fate that brought him from a book-lined room in South Adams Hall to the center of the football universe. Look into the quiet corners of the Patriots' success and see a man who seems more fascinated with those who study greatness than those who are great themselves.

Wright Thompson is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at wrightespn@gmail.com. If you are Ernie Adams, please contact the writer.

Join the conversation about "Who is this guy?"