OTL: Growing Up Summitt

NOXVILLE, Tenn. -- He's the "Little Ricky" of women's basketball. Nearly born during a recruiting trip, Tyler Summitt was already in cahoots with his mother in utero.

NOXVILLE, Tenn. -- He's the "Little Ricky" of women's basketball. Nearly born during a recruiting trip, Tyler Summitt was already in cahoots with his mother in utero.

His head was turned sideways, Tennessee coach Pat Summitt says of her only child. And that's what kept him in place while she (almost) finished a visit with prospect Michelle Marciniak in Pennsylvania … then raced to the airport … flew back to Tennessee … and rode in an ambulance to the hospital.

He made his entrance here in Knoxville, just as his mother had intended. "You could say I was born into the basketball world in Tennessee because she was just not having me anywhere else," Tyler says. "When Mom's got her mind made up, there's no changing it."

The thing is, telling Tyler's birth story to women's hoops followers is like "explaining" to Hitchcock devotees how he made "Rope" appear to be a continuous take with no cuts. Or "informing" Springsteen fans that he recorded "Nebraska" at home.

Hey, they think, doesn't everybody know the tale of Tyler's arrival? Just as folks in the 1950s knew Lucille Ball gave birth to Desi Arnaz Jr. on the same day in January 1953 the birth episode of Little Ricky, his television alter ego, aired. At the time, his mother's program was at its pinnacle: No. 1 in the ratings that season by 13 percentage points over the No. 2 show.

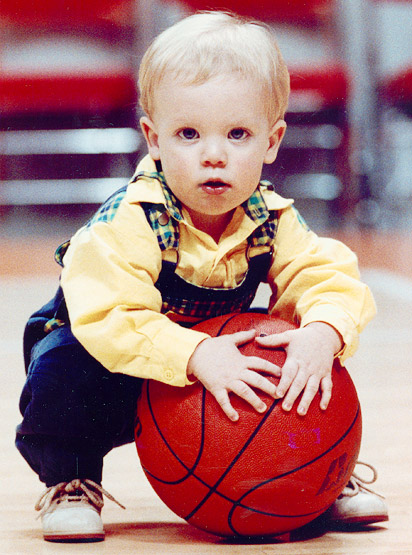

Little Tyler arrived in September 1990. At the time, his mother's program was at what qualifies as a nadir at Tennessee: six months after what remains Pat Summitt's most painful defeat. Of course, nadirs don't have a long shelf life at the nation's most successful women's basketball program, and so, just six months later one of Summitt's sweetest victories arrived. That March 1991 win was No. 442 in Summitt's career. It brought Tennessee a third NCAA title and Tyler his first trip -- in his mother's arms -- up a ladder to cut down the most important of nets.

Tennessee has eight championships now, and increasing that number is what drives Summitt. Her next win will be No. 1,000, making her the first college coach, man or woman, to hit four figures. (For more on her historic quest, check out "At the Summitt.") To Summitt, 1,000 is just part of the process of getting to, she hopes, No. 9. So you have to ask someone else, such as Tyler, what 1,000 really means.

"It's astonishing," he says. "She's done so much for the game."

There have been 587 victories for Tennessee since Summitt, a surrogate mother to hundreds of "daughters" in 35 seasons in Knoxville, became flesh-and-blood mother to a son. A boy now on the brink of manhood -- could Little Tyler possibly be 18 already? -- he shares her competitiveness, her impeccable Southern manners, her firm handshake. "Tyler is so close to his mom, and he's really supported her through the years," Summitt's mother, Hazel Head, says. "He's just a good, good boy."

Let's take a look at Pat Summitt's march to 1,000 through the eyes of the apple of her eye, an apple proud to sit near the towering tree from which it fell.

Tyler Summitt is walking through the bowels of Thompson-Boling Arena, his second home, when an usher calls to him. "Tyler, don't forget to sign my autograph book!" the woman says. "You don't have to do it right now, but don't forget!"

The young man in an orange polo shirt and khakis certainly will not forget the request. He knows it's important, almost a tradition. He has signed the same woman's autograph book for many years now. "Yes, ma'am," he says, "I promise I'll do that today."

With that settled, Tyler is ready to begin talking about something he truly loves to discuss -- his mom's career -- when he is interrupted by a more urgent request. "I'll be right back," he promises. "I need to go help my mom get my granny in here."

Giving Mom a hand has been Tyler's motivation from almost his earliest consciousness. "When I was little, the scoreboard didn't mean anything -- it was just, 'Is Mom happy or mad?'" he says. "I just wanted to help her because she seemed like she had so much on her. She'd come in from after a game or practice and have to cook for me. She always does that.

"Right up to the last second of the day, she was doing something and never got much sleep. So it was a privilege to do things like carry the stool at games when I was little. I thought that was awesome. It was where Mom was going to sit at timeouts, so I felt like I was contributing."

The Legend of Tyler includes his first "contribution," when he was still an infant. Daedra Charles -- now an assistant coach for Summitt -- kissed the baby before each game for good luck, but she didn't get the chance to before the 1991 NCAA title contest against Virginia. That had to be remedied, and it was when Tyler was passed down from the stands at halftime.

Tennessee won 70-67 in overtime.

That victory was sweet revenge for what had happened the previous season, when Virginia won the 1990 East Regional final and kept Tennessee from playing in the Final Four it would be hosting at Thompson-Boling. Summitt always has said that was her toughest loss, but she didn't really have a chance to grieve properly. She had to quickly pull herself together for two reasons: She wanted to send an upbeat appeal to Tennessee fans to still fill the arena for the good of women's basketball (they did), and she needed to focus on her health.

"I remember getting in the car on the way back to the airport after that loss, and I just broke down," Summitt says. "Not many people knew I was pregnant at the time. But it was probably the best thing for me to know that I couldn't emotionally just cave in.

"That really helped me put life in perspective. It really wasn't life or death; it was a basketball game. And as much as it hurt to have lost, knowing that I was going to have a child, it kept me in focus."

Summitt was 38 when Tyler was born, and she already had been coach at Tennessee for 16 seasons. She'd grown up on a farm in Henrietta, Tenn., the fourth of five children and the first daughter. She says her mother was the hardest worker in the family and a very gentle person. But her father, Richard, was the never-satisfied task-masker. He expected Pat to perform all the same grueling outdoor labors as her three older brothers. So while Summitt coached women, she definitely understood boys.

And she knew from an ultrasound that Tyler was going to be a boy.

"I thought that was probably a good thing," she says, chuckling. "Because if it had been a girl, I'd have had her dribbling the basketball when she was just a few months old. But Tyler and I have a really special bond. I think mothers and sons sometimes have it, and fathers and daughters. He started traveling with me when he was 14 days old. I wanted him to experience as much as he could."

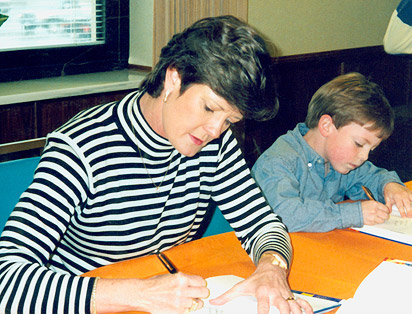

Tyler didn't know or couldn't quite recall much of his earliest history until Washington Post columnist and author Sally Jenkins began doing interviews for the 1998 books she co-wrote with Summitt, "Reach for the Summitt" and "Raise the Roof."

"That's when I started really listening to all the stories," Tyler says. "Before that, I'd go with my mom when she'd be giving speeches for companies and stuff, but it would be like, 'Oh, Mom's talking, I'll just finish my dinner now.' But when Sally came over and we started going through the stories, that was when it all started to sink in."

Like the time Tyler got mad at his mother for yelling at his buddy. "I would always sit at the back of the bus with Mom's players going to and from the games. I got really close to Kellie Jolly. She was my second 'favorite' player. Vonda Ward had been my first.

"Anyway, we were in the NCAA tournament, and my mom took Kellie out of the game and just screamed at her. Mom would always come down to the end of the bench and talk to me during games, which I thought was cool. It was my time to shine."

But in this instance, Summitt encountered one angry little boy. "I was like, 'Mom, you were mean to Kellie. You shouldn't have done that,'" Tyler says. "Mom said, 'Tyler, Kellie was playing horribly.' And I said, 'Well, I'm sleeping in the garage tonight with my cat.'

"She still tells that story to everybody."

So, did he actually follow through and bunk in the garage? "I did not," he says, laughing. "She definitely won that argument. Like everything else."

Lessons that were so important for her players, of course, were even more important to Summitt to pass on to her son. "She's big on communicating -- on or off the court," he says, recounting a story when he was around 4 years old. "Once, I was inside the house with her, then I went outside to the dock. There's about 40 steps down to the dock -- you'll see why that number matters in a minute. Anyway, I was fishing and she was cooking. And then she came out and screamed my name. She was worried. I didn't understand why at first. It kinda scared me that she was so emotional. She said, 'You can go anywhere you want. You just have to tell me first.'"

Tyler thought the point was made. Not quite.

"She and my dad talked, and he came down there," Tyler says. "And I got a spanking for every single step coming back up. Forty steps. It was the worst. But I always communicated after that.

"That's the thing about Mom, it's always one lesson. Then, lesson learned. I lied to her one time. I was about 3 or 4 years old. She asked me if I'd taken a nap at preschool. I hated naps. But I said, 'Yeah.'

"She said, 'Did you really?' I said, 'Um … yeah.' She could tell. One more time, 'Are you sure?' I said, 'No, I didn't.'"

They were in her office, and she told him to take a seat.

"Everybody who walked by the door, she'd say to them, 'Did you ever lie?'" he says. "They'd say, 'Yeah.'

"'Well, do you lie anymore?' They'd say, 'Heck, no.'"

One day Summitt came home and found Tyler on his bed crying, a basketball tucked under each arm. He had been cut during tryouts for his middle school team. "Truthfully, I wasn't very good," he says. "I thought because I'd always been around basketball, I could walk in and make the team."

Summitt asked him whether he really deserved a spot on the roster.

"I said, 'No, probably not,'" he says. "And she said, 'You have to work harder. I promise you if you wear out both those basketballs, you'll make the team next year.' I said, 'Will you help me?'"

Summitt was wary of pushing him or of turning into his source of motivation. She wanted that to come from within him. "She'd always told me that I had to start my own engine," Tyler says. "She'd help if I needed her to, but it was going to have to be me who put the work in. I made the team the next year, and I'm still playing now."

Tyler is a senior guard for The Webb School in Knoxville. He might play college basketball somewhere. Or he might go to Tennessee and become part of the male practice squad for his mom's team. He grew up in an orange palace where his mom was the queen and he was a cherished little prince. Everywhere he went, he saw people seeking autographs from his mother and her players, cameras following them, reporters asking questions. His father, R.B. Summitt, is divorced from Pat now, but he was a longtime fixture at games, a partner in the pursuit of women's basketball excellence. So all the adults in Tyler's life reinforced for him that what his mother and her team did was very important.

"I could never do for the game what she has," he says. "But I definitely can see myself on the sidelines. I can't wait to have that chance. That's what I want to do someday. And if I do become a coach, I'll probably want to coach women. I feel like it's a more pure game."

Tyler had no idea that anyone would denigrate women's basketball -- or women themselves -- until he reached late middle school. It hit him like a slap in the face when he would hear snide remarks or when other guys at school would razz him. "It really makes me mad they don't have the respect for women they should," he says. "Because I've seen it all my life. I see how hard they work every day in practice. I see how hard my mom works."

He has watched his mother come home from games to study tape for hours -- after she made his dinner. "When I have time, I sit there and watch tape, too, and I'll ask her what she's seeing," he says. "Because I can't see everything she does. I'm watching the ball, and she's seeing all 10 players. She'll point out three things on one play, and I'm like, 'How do you do that?' She says, 'You'll get used to it.'

"But there are definitely times I'm going to bed, and I can still hear her screaming at the TV in the living room."

Tyler says his mom's success is due, most of all, to hard work … but one of his favorite things is to see her not working.

"We went on a sailing trip for a week once," he says. "She's always going 110 miles an hour. She has to learn to just calm down a little. I love it when she relaxes; it makes me feel like she's finally getting a break. And that's when her humorous side comes out. She'll do stuff that nobody would expect her to do. The only time America's ever really saw that was when she sang 'Rocky Top' and had the cheerleader outfit on."

That was in 2007, when Summitt hammed it up at a Tennessee men's game, repaying a gesture of support from coaching counterpart Bruce Pearl, who had come to a women's game in orange body paint.

"That's the side of her I get to see a lot," Tyler says, although he didn't actually see his mom's performance. He had his head in his hands, willing her to get through it without any embarrassment. "My friends were poking me, and I said, 'No, I'm not watching,'" he says. "She had been singing loudly the night before in the shower. I'd heard that and thought, 'Oh, Lord, here we go.'"

Tyler knows he didn't drive a tractor until his back ached or learn to throw huge hay bales or do sunup-to-sundown chores for a stern father who struggled to show affection no matter how much he felt it. That was Pat's life growing up. Instead, Tyler has traveled all over, lived in a beautiful home on the Tennessee River and thinks he has been blessed to have dozens of "big sisters." The dirt and grit of scratching out a living on a farm isn't buried deeply under his fingernails the way it was for his mom.

And maybe that is why Tyler's head was turned in the womb: Even then, he was trying to look up to her.

There will likely be another Coach Summitt on the sideline someday, maybe even at Tennessee. She is 56 and nowhere close to retiring, and Tyler dreams of being an assistant to her. He knows he might have to work somewhere else, though, and thinks that will be OK, too. Except, he can't imagine looking over at the opponent … and seeing his mom.

"Well, I'll tell you one thing," he says. "She'd be the last person I'd want to coach against."

Mechelle Voepel is a regular contributor to ESPN.com. She can be reached at mvoepel123@yahoo.com.

Join the conversation about "Growing Up Summitt."