Penny Hardaway comes home

Can Memphis' favorite son restore the Tigers to their former glory?

In a high school gym at the parched edge of the Las Vegas Valley, a row of polo-shirt-clad coaches sits faithfully in the folding chairs along the baseline as if in church pews. Bill Self of Kansas. Sean Miller of Arizona. Duke's Mike Krzyzewski was there a little earlier.

Anfernee "Penny" Hardaway is running late, as is his habit. He is one of the last coaches through the gym's side entrance and into his seat, plopping down between retired NBA veteran Mike Miller and former NBA player and head coach Sam Mitchell, now his assistants at Memphis. They cut a striking image, Miller at 6-foot-8, Hardaway at 6-foot-7 and Mitchell at 6-foot-6, looking more like an aging NBA frontline than a college coaching staff. This is one of their first public appearances on the recruiting trail.

A wave of murmurs ripples through the crowd, as the attention in the half-full gym shifts briefly from a lopsided game on the court to the baseline.

"I could feel it," Hardaway says later, "the buzz with the kids and with the coaches when we walk in."

Hardaway signs an autograph, cheerfully greets a couple of parents who wander over from the stands and spends several minutes with his phone tucked between his shoulder and ear, doing his best to give attention to both the conversation and the action on the floor.

He is here in the final week of July for the Las Vegas Summer Showcase, one of the last tournaments of the summer-evaluation period for recruits. This event, one of a handful being held around the city, distinguishes itself from others by promising the participation of 7-foot center James Wiseman, the top-ranked recruit in ESPN's rankings of the Class of 2019.

Joel Anderson sits down with Penny Hardaway to discuss his love for Memphis and his new role as the head coach of the Memphis Tigers.

Wiseman played his way into the No. 1 spot while a member of Hardaway's team at Memphis East High School, where a few months earlier they'd won the school's third consecutive state championship, and his Nike-affiliated, grassroots Team Penny program. Kentucky has been considered the leader for most of Wiseman's recruitment, but Hardaway's move to Memphis turned it into what many recruiting analysts consider a two-team race.

Memphis officials made it clear that they expect Hardaway to be the same kind of draw for Wiseman and other five-star recruits that he was on his meteoric rise through the coaching ranks.

"If your goal is to be a Division I basketball player and go to the NBA," says Memphis president David Rudd, "why would you not want to work with people who have been successful doing it?"

The program, which hasn't been to the NCAA tournament in the past four seasons, turned to its best-known alumnus, hoping his fame and connections could help it reclaim its former glory and navigate the labyrinthine network of relationships with shoe and apparel companies, families, coaches and fickle teenage athletic phenoms.

"A lot of the kids gave a lot of positive feedback about if I ever became a coach, they would love to play in our program," Hardaway says. "And I was very confident that we would be able to get the top-tier players to come in."

That's how, only seven years after unwittingly launching his coaching career at the middle school in his old neighborhood, Hardaway finds himself in a light-blue Memphis polo on a folding chair along with coaches from the likes of Michigan, Florida State and UCLA.

Wiseman, the headliner of the tournament, feels tired and wouldn't play this evening or for the rest of the tournament; he sits on the bench in street clothes.

No matter. Hardaway holds his spot on the baseline the entire game, looking after his former player and current top priority with Miller and Mitchell by his side -- an NBA-caliber show of force for recruits and other coaches.

"Good luck to the other college coaches," says Ernie Kuyper, president of Hoop City BC and a cousin of Mike Miller's, who saw his program weaken as Team Penny quickly became the city's top AAU program. "Thank goodness he's out of my field."

Hardaway, with freshman Ryan Boyce (center) and senior Mike Parks, enters his first season as head coach with some lofty expectations from Memphis fans. Robby Klein

IN BRINGING PENNY home, Memphis is following a dog-eared blueprint: turning to a former star to freshen up a program gone stale. That ploy has mostly produced disappointing homecomings, such as Connecticut's Kevin Ollie, who won a national title in 2014 but was fired in March after consecutive losing seasons (ESPN reported earlier this year that he's facing an ethics violation charge by the NCAA), St. John's Chris Mullin (38-60 in three years) and Houston's Clyde Drexler (19-39 in two years before resigning).

Memphis tried this more than 30 years ago with Larry Finch, who, as a star point guard, led the Tigers to the national championship game in 1973. He was greeted as a savior when he became head coach in 1986; Memphis magazine released an issue that November with his picture under the headline, "Can This Man Save Memphis State Basketball?"

He didn't: Finch, who became the winningest coach in program history, was nonetheless pushed out 11 years later.

Because of those high-profile flops and messy divorces, Hardaway understands the undercurrent of skepticism -- rarely spoken publicly, with the exception of a few outlets in rival areas -- about his chances to succeed at Memphis.

"Oh, I get it," Hardaway says. "But the difference in me and them is that I coached middle school, I coached high school, I coached AAU. So I have a better understanding of the kids."

Drexler, whose tenure at Houston came immediately after his retirement from a 15-year NBA career, says Hardaway's experience working with younger basketball players is much more valuable than going to college directly from the pros.

"The fact is that he's been coaching these kids already," says Drexler, a friend of Hardaway's. "But I always tell him I think this is going to hurt his golf game because recruiting is a full-time job."

Indeed, Hardaway's familiarity with the nation's top recruits made him the obvious choice for Memphis despite his total lack of college-coaching experience.

Only days after the tournament in Las Vegas, five-star forward D.J. Jeffries became the first Kentucky recruit under head coach John Calipari to decommit and reopen his recruitment. Now connect the dots: Jeffries is from Olive Branch, Mississippi, only about a 20-minute drive from the Memphis campus. He played for Hardaway's grassroots program. His father, Corey Jeffries, grew up in the area and rooted for Hardaway and the Tigers.

"Every basketball player in the area wants to go to Memphis," Corey Jeffries says. "Before Penny came, we didn't hear all that."

Hardaway's deep ties to the community have already paid off; he landed a commitment from five-star recruit D.J. Jeffries on Saturday. Robby Klein for ESPN

MORE THAN 500 people show up on a gloomy Tuesday afternoon at the Laurie-Walton Family Basketball Center, the year-old 62,000-square-foot facility fronted by seven large, white columns that give it the look of a palatial art museum. The Memphis Rebounders, the booster club for the men's basketball program, found the rare opening in Hardaway's schedule and planned a meet-and-greet with club members.

In a corner against a wall are Mitchell, Miller and other members of Hardaway's staff. Over plates of pulled chicken and pork, baked beans and coleslaw, silver-haired boosters and stooped former Tigers players pack into a cavernous lobby dubbed the "Hall of Traditions" to greet Hardaway.

"I'm blown away," says Harold Byrd, president of the club and a local bank. "We've had a lot of impressive receptions. But none that were this warm."

About a half hour after the scheduled start, Hardaway hops onstage at the front of the lobby to a standing ovation. The 47-year-old doesn't look all that different from the reed-thin teen he was 30 years ago, though his face has rounded out a little more with age.

Up there by himself, with a microphone, Hardaway gives his guests what they came for.

Someone asks about a preseason conference poll that ranks Memphis eighth in the American Athletic Conference. "I had to realize they've been wrong before and they'll be wrong again," he says. The crowd raucously applauds. He almost playfully invokes the name of Calipari, telling the crowd Kentucky turned down his request to play a game this year. Calipari, whose successful run in Memphis from 2000-09 included a national championship appearance but also NCAA violations that later erased it from the record book, remains persona non grata among die-hard Tigers fans. They roundly boo him.

Hardaway then opens the floor for questions, and a woman eagerly seizes the microphone. She is a former professor of his, she says, someone who has been observing him for more than a quarter-century. "I save everything in the paper that says his name," says Jane Howles Hooker, an associate professor emeritus at Memphis. "Same thing with Elvis."

Hardaway has shown up in the local newspapers for almost 30 years now, dating to his days at Treadwell High School as the nation's top recruit. Still, hard as it might seem to believe, Hardaway -- who would've been the jewel of any recruiting class in 1990 -- had to make the case for his admission into Memphis State. He missed much of his high school senior season with grade problems and would have to sit out his first year in college once he got in. He had to convince wary administrators that he would be serious about school.

"I had to go in and plead my case and say, 'Hey, I'll get it done,'" says Hardaway, who had taken his only other official recruiting visit to Arkansas. "But it was OK, because I wanted to be here that badly."

Hardaway's year off had its highs (he got himself on track academically) and lows (he was shot in the right foot during a robbery attempt in his old neighborhood), but he came out of it eligible, healthy and the most highly anticipated homecoming act in town since Elvis played at old Ellis Auditorium in 1956. His on-court debut came at the Memphis Pyramid, a new, 20,000-seat arena on the banks of the Mississippi River, sometimes jokingly (sometimes not) referred to as "The House That Penny Built."

Hardaway went on to become a two-time All-American and conference player of the year, leading the Tigers to a 43-23 record overall and to within a game of the 1992 Final Four. He declared for the NBA, embarking on a 15-year career that turned him into a household name, but he was ultimately derailed by injuries. He retired in 2008.

Post-Penny, Finch suffered the first -- and only -- losing season of his head-coaching career (13-16) and missed the postseason. He rebounded with 24- and 22-win seasons and consecutive NCAA tournament berths following the addition of another top hometown recruit, 6-foot-11 forward Lorenzen Wright. But Wright's departure to the NBA in 1996 weakened Finch's roster -- Wright was the third player in four years to turn pro early -- and the Tigers stumbled to a 16-15 record the next year.

By that time, the Tigers were playing before a half-empty Pyramid, and recruiting locally had dropped off. Memphis would need another boost: Finch was forced to resign at the end of the 1996-97 season.

"The way the Coach Finch situation was handled was less than the best," Byrd says. "It left a chasm in the program for years."

"The process Larry went through," Finch's wife, Vickie, says, "I'm sure Penny is going to learn from it."

Says Hardaway: "It's eerie because I'm walking in his footsteps."

But Memphis has always put faith in the redemptive powers of Penny.

Hardaway in action against UAB during the 1992 Great Midwest Conference tournament. Richard Mackson/USA TODAY Sports

NONE OF TODAY'S top recruits were even alive when Hardaway was a perennial NBA All-Star for the Orlando Magic. Most aren't old enough to remember when Calipari, Derrick Rose and a 38-win Tigers team came within seconds of winning the program's first national title in 2008; James Wiseman was only 7 years old then. In 2015, The Pyramid was reopened as the second-largest Bass Pro Shops in the world.

Attempts to rebuild the program under youthful Calipari assistant Josh Pastner and venerable former national champion Tubby Smith have produced only two NCAA tournament wins in the past nine seasons and four straight years of finishing no better than fifth in conference play.

Smith barely had a chance to learn his way around town before local media and fans started clamoring publicly for Hardaway. At Smith's introductory news conference in April 2016, one of the first questions was if he'd consider hiring Hardaway as an assistant.

Hardaway's reputation had been rising in the local youth ranks since 2011, when he began sitting in on a few practices at Lester Middle School at the behest of his friend Desmond Merriweather. Most of the boys on Merriweather's team still couldn't figure out how to beat a basic zone defense, often deployed to confuse teams with superior quickness and athleticism.

"So I sat behind the bench and was giving adjustments in a game against a team that they had already lost to," Hardaway recalls. "They ended up beating them pretty handily. And [Merriweather] was like, 'You need to start coming to practice more.'"

Hardaway's first hoop dreams started at Lester, where, as a little boy, he found sanctuary on the asphalt courts outside of the school. Countless hours of shooting on rusted goals set the foundation for his escape from the entrenched poverty and violence of Binghampton, the neighborhood where he was raised and Lester was located.

Coaching with Merriweather, Hardaway took an immediate interest in a precocious, stocky sixth-grader named Alex Lomax. In Lomax, the former NBA All-Star saw a bit of himself: a pass-first point guard and natural leader. "I expected him to come out for a few days, get on a private jet and go back to Hawaii or something," Lomax says of Hardaway. But Hardaway kept coming back. He was there when Merriweather was diagnosed with colon cancer in 2012. And he was there to win three state middle school championships alongside Merriweather before the coach and Lomax moved on to East High.

Hardaway took some time off from coaching but still maintained a presence locally with Team Penny, for which Lomax also played. There, Hardaway wasn't shy about reaching out for help or bringing in new talent to keep the program competitive. His status as the only men's coach to have a signature line of Nike shoes -- the Air Penny Foamposites remain popular with sneakerheads -- gave him entree into the homes of top players who didn't remember his NBA career. He ordered shirts for the team that stated "One for all, all for one, all for Memphis."

Former NBA player Todd Day, who was coaching at a Memphis high school, says he folded his own locally based AAU program when Hardaway called him to help with Team Penny. "Penny was always going to have the best players; he's a magnet," says Day, now the head coach at Philander Smith College in Little Rock, Arkansas. "But he also knows what it takes. He's a refuse-to-fail kind of person."

Other top recruits in the area also couldn't help but notice the sudden shift in prominence. "We had some teammates go over and play with Team Penny," says Corey Jeffries, father of 2019 recruit D.J. "We were looking like, 'Man, we maybe should've went over with them?'" D.J. eventually did.

Merriweather rose to head coach at East but succumbed to his illness in February 2015 during his first season in the role.

Hardaway joined the team as a volunteer assistant for the end of the season, which ended in the state semifinals. Hardaway was the program's top coach for the next three years but didn't officially assume the title of head coach until the fall of 2017 because of a change in state rules about non-faculty members serving as coaches. He led the Mustangs to a 96-8 record and won three straight state titles in Tennessee's largest classification. The last championship was won with contributions from Wiseman and 6-6 wing Ryan Boyce, whose transfers into the school before the year briefly left them ineligible.

"Desmond and I made the plan in middle school," Hardaway says of conversations before Merriweather died that amounted to career planning. "I'm like, 'Wow. We would sit down and talk about this all the time.'"

While Hardaway was thriving at East, Smith didn't sign a single recruit from Memphis. Homegrown stars Dedric and K.J. Lawson transferred to Kansas at the end of Smith's first year after he demoted their father and Tigers assistant Keelon Lawson. Locals grumbled Smith was aloof. Most damning: The Tigers averaged 4,583 fans per home game in 2017-18.

It was no surprise, then, in March when Smith was fired after his second consecutive 13-loss season and fifth-place finish in the AAC. Hardaway agreed on March 19 to become the Tigers' next coach -- an inevitability, Smith now understands. "He probably deserved it when I got it," says Smith, who now coaches at his alma mater, High Point University.

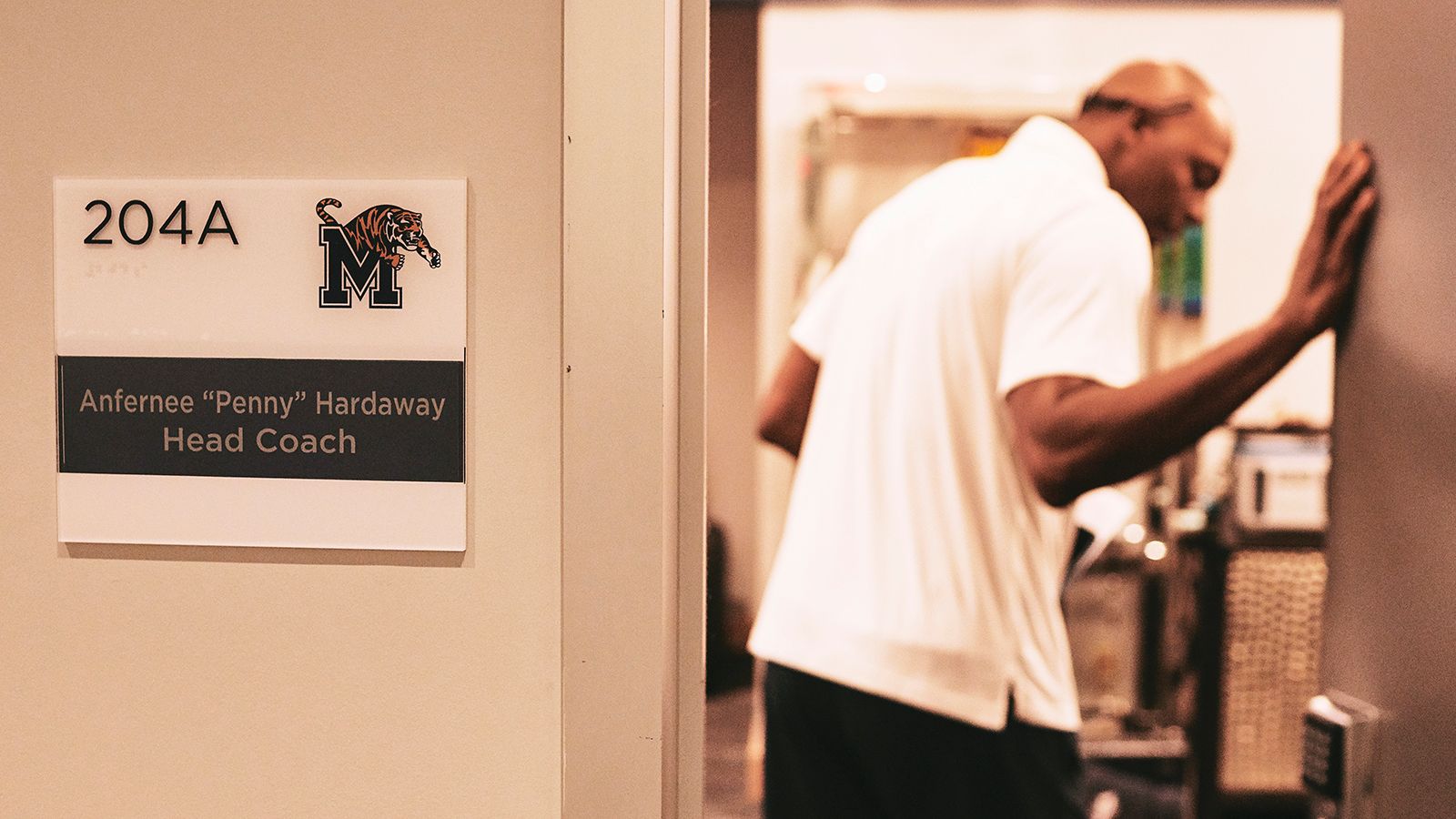

Seven years after Hardaway unwittingly broke into coaching at Lester Middle School, Boyce and Lomax were members of his first recruiting class at Memphis. Hardaway pondered that remarkable journey on a recent late-summer afternoon, impassively retelling the story for a visitor from the Tigers' $21 million practice facility.

"That's how we claimed it," Hardaway says, in the anticlimactic manner of a man who had conquered infinitesimal odds many times before. "And it happened just like that."

A Lil Penny, left, from the '90s Nike ad campaign, stands in the hallway of the Anfernee 'Penny' Hardaway Hall of Fame building on Memphis' campus. Robby Klein for ESPN

OCT. 4 IS the start of homecoming season in Memphis: Fans wait outside the FedEx Forum downtown for hours to get inside for the most highly anticipated basketball practice in recent memory.

They pack the stands, a show of support not seen around these parts in more than a decade. "Last time the Forum was sold out for a Memphis? Feb 23, 2008 vs UTK. For a practice?" tweets Rudd, the school president.

"Memphis Madness" is a daylong catharsis for a program long in the doldrums, from the Finch family sitting in the front row, from Wiseman taking a seat behind the players' bench and joyfully greeting a steady procession of fans, from Hardaway's dramatic, arms-raised entrance to raucous applause. Boyce, the high-flying freshman from East, wins the dunk contest. There are even hometown celebrities, from former Tigers star Elliot Perry to hip hop star Yo Gotti, whose mother is Hardaway's neighbor and who closes out the night with a rendition of his hit "Rake It Up."

It seems like a triumph, and yet afterward, Hardaway faces questions about who didn't show up: namely Justin Timberlake and Drake, who had been rumored special guests.

"I was really trying to get Justin [Timberlake]; of course, he's busy," Hardaway tells reporters. "We really never tried to get Drake."

The next morning, a column in the student newspaper criticizes Hardaway and the school for not doing more to squelch those rumors, even quoting a handful of disappointed students. A local reporter and radio host fields dozens of complaints for fueling that speculation.

Welcome back to Memphis, Penny.

Keeping fans happy about the on-court product likely won't come easily, either, given the heightened expectations around town.

In most preseason predictions, the Tigers have been expected to be a middle-of-the-road team. They return high-scoring guard Jeremiah Martin (18.9 points per game) and welcome a recruiting class that wasn't ranked among the ESPN's RecruitingNation top 40 despite the late signings of Lomax and Tyler Harris, another four-star guard from Memphis.

Then, on Saturday, Jeffries announces he will be attending Memphis. "Happy to be a tiger I'm staying home," he tweets.

He'll join a roster that has some talent but probably not enough to advance too far into March -- a good coach could make a big difference.

"I like being the underdog," says Mike Parks Jr., a 6-8 junior forward who started all 34 games last season and averaged 8.1 points and 4.5 rebounds. "We're going to prove them wrong, that's all it is."

Parks is a prime example of the pitch being made inside and outside of the program, as Hardaway and his staff asked the senior to drop some pounds (his listed weight has gone from 270 to 250 in the past year) and start shooting more jumpers in preparation for a more fast-paced offensive scheme. They've told him that's the key to making it to the next level.

"I wanted to expand my game more," Parks says, "Do different things that NBA players do because that's where I'm trying to go."

In Hardaway, Parks and Lomax -- like the Memphis fans who will cheer for them this season -- see someone who made that journey and back. The memory of what was and the hope of what could be.