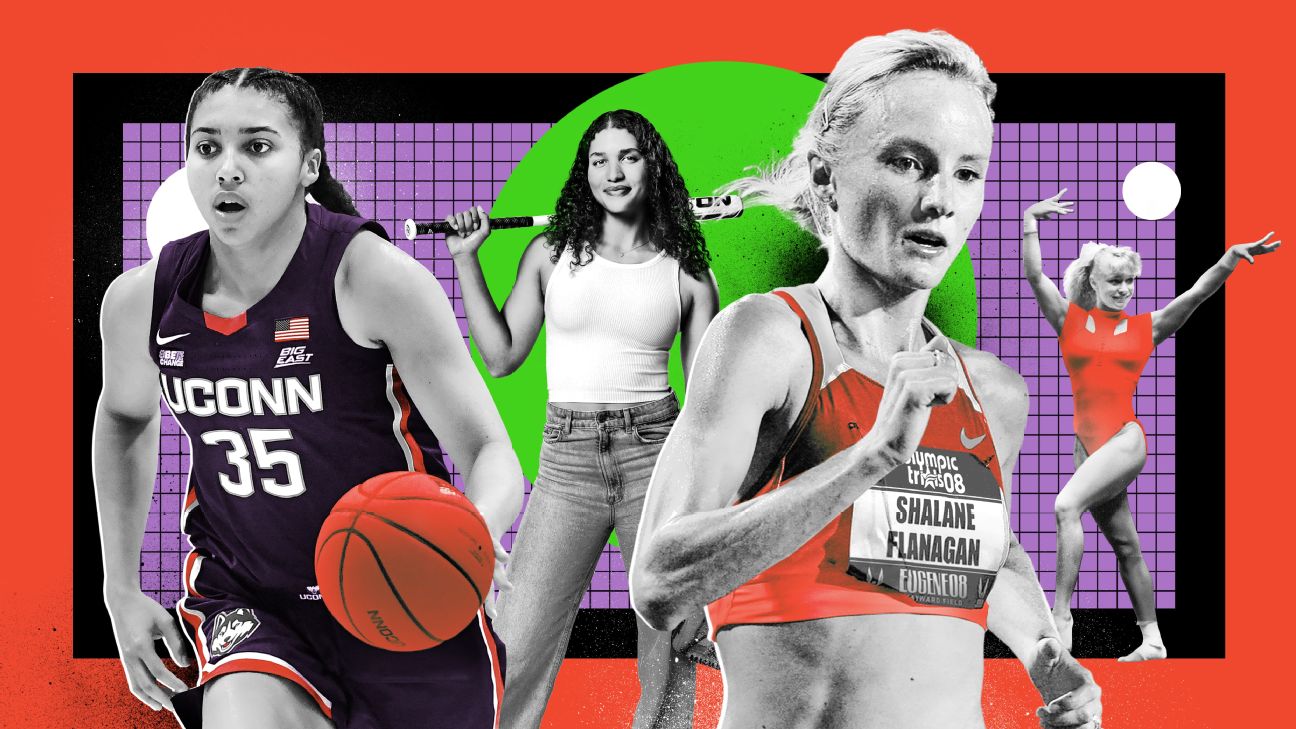

Sports legacies Title IX created

Seven families discuss the multigenerational, maternal lineages they've built across the 50 years since the passage of Title IX.

Sports legacies Title IX created

Seven families discuss the multigenerational, maternal lineages they've built across the 50 years since the passage of Title IX.

Before 1972, girls and women who played sports had little expectation of gender equity. Most weren't allowed to cross the half-court line in basketball. They made their own clothes and ran in makeshift shoes. They fought their administrations for access to equipment, transportation and locker rooms. Now, 50 years after the passing of Title IX, the federal civil rights law prohibiting sex-based discrimination in any educational institution receiving federal funding, women athletes have more opportunity than ever.

In June, ESPN and The Walt Disney Company are launching their

"Fifty/50 Month" initiative, a wide-ranging content plan focused

on the intersection of women, sports, culture and the fight for

equality.

Read the stories

ESPN spoke with women athletes across generations from seven families about their NCAA experiences and beyond. They discussed how conditions have changed in their lifetimes and how wide the gap remains between men's and women's athletic programs.

[I feel] lucky to be playing today, to get all the perks that everyone before me, like my mom and even before her, fought so hard for.”

Azzi Fudd“

How it started

Katie Fudd found her voice, and she’s not afraid to use it

When Katie Fudd was being recruited in the 1990s, she didn't have much information. There were very few women's games on TV, highlight reels did not exist and players couldn't communicate with coaches often. The only time she could get a feel for a program was to officially visit.

She chose NC State, where she was ACC Rookie of the Year, but struggled to fit in with the team. She believes it was because she was so quiet then and didn't know how to stand up for herself. She transferred to Georgetown after one year.

Georgetown was a better fit, but she was shocked by the conditions the women played in. "Coming from NC State where, honestly, everything was really good ... you go to Georgetown and it was [like] literally no one existed except the men's team," she said.

We couldn’t walk through our own gym when the men were practicing. ... Not only did they walk through our gym while we were practicing, they cut across our court.”

KATIE FUDD

She said she was once told to leave the gym because a male athlete was also there -- even though she had arrived first.

By her senior year, Katie was no longer willing to put up with this treatment quietly. At a lecture full of men and women's athletes, she said, "I don't care how many pairs of shoes you get. I don't care if you fly on a private plane and we take a bus. I'm saying, can we walk in our own gym without you kicking us out? Do we have to feel like we don't matter as much?"

"To this day, it still irritates me," she said.

When it came time for Azzi to choose a college, Katie paid close attention to how women athletes were treated compared to the men. She pushes Azzi to speak up for herself and confront problems head-on.

I was young. ... I just didn’t know how to stand up for myself. That's something we try to teach our kids ...”

[My mom is] huge on me trying to learn self-advocacy. ... Those are things that she picked up on from college and was trying to tell me ...”

How it's going

Azzi Fudd carries her mom’s legacy -- and her jump shot

Azzi said she grew up in the gym, since both her mother and father, Tim Fudd, are coaches, trainers and former college hoopsters. While they say she had a choice over which sport she played, "I'm not sure how much I buy it," Azzi said with a laugh.

She credited both of her parents with shaping her game. Katie said their mantra was to always do a little more than everyone else. After a practice, she'd tell Azzi to take another 25 shots or do some more ball handling. "It's the people who are willing to put in the extra time all the time," Katie said.

Azzi and her mom have the same jump shot, which Katie taught her over one summer. "It was so boring, but it's worth it now," Azzi said. She once saw a photo of Katie taking a jump shot and then a photo of herself in high school. "Our arms, our form -- it all looks the exact same."

Azzi hasn't seen Katie play much, but during a recruiting trip, UConn showed her clips of her mom playing against the Huskies. She said she thinks she'd beat Katie, who went into the WNBA for a season but never played because of injury. It would be "a good game," Azzi said.

"Obviously I'm better. She's old," Azzi said. "But she always tells me, 'I was mean. I was so much more mean than you. I would destroy you in my prime.'"

St. John's College High School, 2019 WCAC champions

Katie helps Azzi with the mental side of the game, like how to cope with injury. When Azzi tore her ACL in 2019, Katie knew exactly what had happened because she had done the same to both her knees during her career. "I tell her she gave me bad genes," Azzi jokes.

But knowing that her mother had been through the injury helped Azzi get through it. "There were a lot of tears, a lot of bad days, but knowing I had [my mom] on my side made it a lot better," she said.

While things have improved for women, Katie pointed out that even this year, the Georgetown women's team, which plays on campus, wasn't allowed to have fans at home games, while the men's team, which plays in downtown Washington, D.C., could.

““We’re not there yet. It’s my generation’s turn to speak up and make it better for the next generation.”

AZZI FUDD

How it started

When there was no path, Cheryl Treworgy made her own

Cheryl started running at 16. The North Central (Indianapolis) High School track coach invited her to practice, but she was soon told by the school board she couldn't run with the boys.

Eventually they let her run on school property, but only on the other side of the school. She attracted local media, which she felt tried to normalize her running by including her body measurements or posing her on the start line in her majorette uniform.

Six years before the passage of Title IX, Indiana State University offered Cheryl a scholarship, which she credits to the efforts of Dr. Eleanor Forsythe St. John, who ran the physical education department at the time.

Cheryl was the first woman to receive an athletic scholarship from Indiana State, at a time when they didn't exist for women.

In 1971, Cheryl ran the Culver City Marathon, though women's marathon was not yet recognized as an event. In the final stretch, a man tried to run her off the track. But she set a new world record of 2:49:40 and became the first woman to break 2:50:00.

You know, men weren’t used to sharing.”

CHERYL TREWORGY

Cheryl stayed involved in sports long after her own running career. She taught P.E. and worked as an athletic director at Oklahoma State and assistant athletic director and running coach at Michigan State.

She began producing athletic clothes for women, because they didn't exist. She designed sports bras and holds two sports bra patents.

Like many women, Cheryl changed her name upon marriage. She asked that all of her last names -- Pedlow, Bridges, Flanagan and Treworgy -- be included. "Without using all of my names, I lose my identity and place in the world in the different phases of my life," she said.

Everything was about her looks, not about her athletic prowess or achievements.”

I made a lot of my own clothes ... Those clothes to fit an athletic body weren’t available, meaning it wasn't the small waist, larger hips body.”

How it's going

Shalane Flanagan, serial champion

After Cheryl gave birth to Shalane, she took her to work with her. "When you read articles that say [Shalane] grew up in the back of a running store, it's totally true," Cheryl said.

Cheryl and Shalane, Mother's Day race in Colorado

In her 50s, Cheryl became a sports photographer and regularly covered her daughter's meets. "My collegiate career is well documented because of her," Shalane said.

Cheryl at the 2015 Boston Marathon. Shalane placed ninth

"That was one of the reasons I started shooting," Cheryl said. "I didn't have any photos of me competing, and I wanted to make sure my kids and other people's kids had those moments."

The thing that I truly am jealous of [today] are other girls to run with.”

CHERYL TREWORGY

Shalane went on to be UNC's first-ever cross-country national champion. She competed in four Olympics and won silver in the 10,000-meter in 2008. In 2017, she became the first American woman to win the New York City Marathon in 40 years.

Shalane won the New York Marathon in 2017, the first American woman to do so in 40 years.

Shalane, center, won silver in the 10,000-meter race at the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

Shalane beat Kara Goucher and Amy Begley at Olympic trials to guarantee her spot in Beijing.

Shalane celebrates with a friend after completing the 2021 New York City Marathon, which she ran in 2:33:32.

Shalane, right, hugs compatriot Emily Infeld, who won bronze in the 10,000-meter at the 2015 world championships.

Shalane still runs marathons -- including six in six weeks last year -- and is now coaching and raising her son, Jack, who just turned 2. She hopes to encourage more women to train together, partly because her mom never had anyone to run with.

Shalane and Jack

““I can remember the resistance from men saying, ‘Are you serious? We got to give scholarships to women? Their skills are so far behind.’ I said, ‘You just wait.’ And it only took one generation.”

CHERYL TREWORGY

How it started

Maureen Brady is a superstar in a family of stars

Maureen grew up in a family of athletes, including her brother Tom (yes, that one). She started playing softball when she was about 5 and pitched at Fresno State for longtime coach Margie Wright.

Maureen credits Wright with fighting for equity for the team.

I remember my coach working really, really hard for women and for equal opportunities back then.”

MAUREEN BRADY

Coach Margie Wright, Fresno State, 1986-2012

Maureen, an All-American in 1994, led NCAA Division I that year with 36 wins.

How it's going

Maya Brady is living her longtime goal of competing for UCLA

Maya played many sports growing up, but her favorites were soccer and softball. When she was around 12, she had to choose between them. "I don't know what drew me to softball," Maya said, "but maybe since my mom played, I was inspired to be like her."

Maya's "Uncle Tommy" once called her "the most dominant athlete in the family."

Would she agree with that? "1,000 percent," Maya said with a laugh.

Her mom is a little more circumspect. "She's probably the most athletic at this point," Maureen said. "There's a lot of younger kids coming up, though."

Maureen helps Maya understand what a pitcher might be thinking, though Maya didn't want to share any secrets. "She's exposing me," Maya said of her mom. "I'm going to get all these different pitches now."

I think as a pitcher ... you just don’t want anybody to hit off you and you have to take it personally that they think they can.”

Whenever I face a pitcher, I just think, ‘Oh, so you think you can get me out? That's funny.’”

Maya hopes softball will continue to grow and to receive more attention from major networks and outlets.

““When people watch softball, they realize, ‘Wow, this is a sport I enjoy.’ But I don’t think we’re getting represented on the biggest stages.”

MAYA BRADY

How it started

When UNC formed its women’s basketball program, Marsha Lake was there

At 6-foot-1, Marsha really had no choice but to play hoops. Her freshman year of college -- nine months before Title IX was enacted -- UNC started its women's sports program with seven sports, including basketball. Marsha made the first-ever team and became the program's first All American.

She remembers having four coaches in four years -- "it was the PE instructor who chose the short straw" -- and getting 50 cents for meals at away games. "You could buy a hamburger but you couldn't [also] buy a drink," she said.

Around the time Title IX was passed, a local sportscaster asked her about conditions for the women's team. Did they have basketballs? Yes, but not enough for all the girls. Did they have uniforms? Yes, but not sweats. How did they get to games? In the university's station wagons.

After the interview aired, Marsha said the athletic director berated her for what she said. But the women's team soon got more balls, some sweats and was eventually allowed to use the men's bus.

I hope I had a little bit to do with that, me and my big mouth and that teeny TV station in North Carolina.”

MARSHA LAKE

The women didn't have access to a locker room. Legendary UNC men's coach Dean Smith once saw them sitting outside the men's locker room during halftime and asked why they were there, Marsha said. After that, Smith let them use the men's locker room during halftimes.

In 1973, Marsha traveled to Moscow for the World University Games. It was the first time USA women competed in basketball and would pave the way for the women's Olympic team. People from her town sent telegrams wishing her luck.

One of Marsha's, left circle, Team USA teammates was a young woman who even then showed the drive she would become known for as a coach: Pat Summitt, right circle.

They came home with the silver medal after losing to the undefeated host country, the Soviet Union. "That was the biggest deal ever," Marsha said. "Nobody from Dunn, North Carolina, had ever done anything like that."

Now-Hornets GM Mitch Kupchak, four-time UNC All-American runner Reggie McAfee and Marsha, 1973 World University Games

After graduating, Marsha stopped playing and started teaching math at a local college. "There was nowhere for me to play," she said. Women's basketball made its Olympic debut the next year, at the 1976 Games in Montreal. Marsha was invited to try out, but she chose not to. "I will lament that my entire life," she said. She became pregnant with Shea soon after.

How it's going

Shea Ralph, a UConn mainstay, has struck out on her own

Marsha figured Shea would grow up to be tall and could play center, like her, but Marsha made sure Shea honed her ball-handling skills when she was young. That way, she could play any position.

Marsha set up games against boys and men at the community college gym. "Boy, do you get better when you have to pass around men or dribble around men or shoot around men," Marsha said.

Shea teases her mom about her game, even though she said Marsha is the better player. (Marsha said Shea is better.) "They played a lot of zone defense. And I'm like, 'Mom, you didn't go anywhere. You just stood in the middle of the lane with your hands up,'" Shea joked.

Marsha and Shea, 1995 Dial Awards

When Shea's talent became apparent, Marsha called on an old friend. Summitt invited them to her summer camps at Tennessee. Shea was only in middle school, but Summitt took the time to work with her. "I don't know that I ever told her the impact that made on me, but it did," Shea said. "It still does."

Summer camps convinced Shea to dedicate her life to basketball and introduced her to like-minded people. "I didn't feel as isolated or alone," she said.

Marsha assumed Shea would play for Summitt at Tennessee, and even bought the jacket. But Shea wasn't sure where to go -- until she spoke with Geno Auriemma. "The first conversation I had with him, I wasn't even on campus," Shea said. "I was like, 'I'm going to play for him.'"

Shea comforts a teammate after NCAA tournament semifinals loss

Ralph captained UConn to the national championship in 2000 and won several individual accolades, including MVP at the Final Four.

The WNBA drafted Shea, but she never played due to a series of knee injuries. She struggled with losing a core piece of her identity. "I couldn't watch basketball," she said. "I didn't want anything to do with it." After about a year, she decided to try coaching and got a job at Pittsburgh. She then reunited with Auriemma at UConn as an assistant coach for 13 seasons until she took the top job at Vanderbilt last year.

Ralph's struggles shaped her coaching philosophy. She encourages her players to see themselves as people, not just athletes, and to develop their interests beyond the court.

She and her husband, Tom Garrick, a former NBA player who is now on her coaching staff, have a 3-year-old daughter, Maysen. Shea is proud Maysen is growing up in an environment in which young women play college sports and her mom is in a leadership role. Maysen is a budding hoopster herself. "She shoots underhand, but we had a practice where she shot the whole time," Shea said. "She made 36 baskets."

[I wanted] to be a great role model for my daughter and for all the other women who want to do this. I know I can be great at all of it. All I needed was an opportunity to show it.”

SHEA RALPH on staying in coaching after giving birth to her daughter

Coaching is one area where women have not made progress under Title IX. Women head coaches lead 43% of all D-I women's teams, and only one woman, former WNBA pro Tamara Moore, is head coach of a men's college hoops team at any level.

People have said to me, ‘you’re living vicariously through Shea.’ And I said, ‘No, I did pretty damn good myself.’”

She still let me make my own mistakes ... now that I’m in the actual job and I see how many people are tugging at student athletes to try to get them to certain places, I respect her even more.”

But Shea is clear about one thing she's going to do differently from Marsha. When recruitment time rolls around, Maysen won't have a choice. "She's playing for Vanderbilt," Shea said.

““When I think about how hard it is for all of us, I think about what my mom did. She never gave up, so I can’t. ... I have to keep fighting for my players, for my daughter, for her daughter."

SHEA RALPH

How it started

Gail Hillmon-Williams paved the way for a family of champions

In 1977, Gail went to Bethune Cookman, an HBCU in Florida, as a basketball recruit, but came home after just a few weeks to be closer to NaSheema, who was a toddler at the time. She enrolled at Cleveland State and joined the team.

Gail's mother helped her balance school, basketball, work and a baby. Once Gail graduated, she went to work as a probation officer and focused on building a better life for her kids.

Gail, her sisters and their mother

How it's continued

For NaSheema Anderson, defense was the name of the game

NaSheema was inspired to play by watching the women's team at the University of Toledo, where her aunt was an athletic trainer.

She and her high school teammates worked hard to bring crowds to their games. They made pacts with the boys' team to come to each others' games. They sold tickets and held raffles at lunch. They fought the administration on travel and equipment.

My mom would work two, sometimes three jobs, to make sure that I could get where I needed to go to be at basketball on time, and to have the equipment and things that I needed.”

NASHEEMA ANDERSON

One day, when she was 14, she found a pair of piercing blue eyes watching her in the gym. Pat Summitt had come to her high school. Summitt was already producing superstars at that point, but NaSheema had no idea who she was. Four years later, though, her choice came down to Tennessee and Vanderbilt.

Tennessee was the stronger program, but Summitt wanted to use the redshirt year to change NaSheema's game. "She was like, 'I want you to come in, and I want to change you to a 3 [guard],'" NaSheema recalled. "But I was good with my back to the basket. Facing the basket, I felt kind of awkward." She chose Vanderbilt.

He made sure that everything was equal. When the locker rooms got redone, the locker rooms were 100% the same, just on different sides of the building.”

NASHEEMA ANDERSON on Vanderbilt coach Jim Foster

Her freshman year, she found out she was pregnant. She kept playing, and Vandy won the SEC tournament, beating Tennessee in the final. She turned down USA Basketball's invitation to play that summer.

She went home to Ohio, had her baby in August and returned to Vanderbilt to play two weeks later. Gail took care of the baby and drove the 12 hours between Cleveland and Nashville so frequently "the wheels fell off" her green minivan, NaSheema said.

NaSheema's high school jersey retirement, 2019

After college, NaSheema stayed in Nashville to play in the American Basketball League. She remembers practicing in high school gyms and playing in tiny auditoriums. She didn't know how poor the facilities were until she saw her brother, Jawad Williams, play in the NBA. Her first Christmas as a pro, she flew her whole family in and bought them presents. She felt like she'd finally made it.

Then she saw a headline flash across the ESPN ticker: the league had folded. She hadn't been told.

She became pregnant with Naz and moved back to Cleveland. Her husband encouraged her to try the WNBA, but she had two little kids and didn't think she could do both. Looking back, she said she wishes she would have done it differently.

Once I finished college, that was it for me. I went to work and I started building for my kids to have them a future and to play ball or to get a good education.”

I don’t think that I felt supported or had the courage to be like, ‘Oh, I'm going to tote two babies around to these WNBA games.’ Whereas now, I think, we’ve seen that can be done.”

[My mom] talks about how grateful [she is] that I’m able to experience [better conditions]. Of course, it’s upsetting that she wasn’t able to.”

How it's going

Naz Hillmon has earned her seat at the champions table

Naz started playing basketball for a simple reason: She wanted to be just like her mom. "Anything I could do to be just like her," she said. "Her favorite color was purple. I was like, I want my favorite color. Purple."

There's no shortage of champions in Naz's family. In addition to Gail and NaSheema, her great-aunt played at Case Western, her aunt played at Virginia and her uncle played at UNC and in the NBA. When Naz was growing up, they told her she couldn't sit at the champions table.

NaSheema and Naz won the same high school hoops award, 23 years apart

And they're always comparing honors. "That lit a fire under her like no other," NaSheema said.

NaSheema coached Naz briefly, but the two quickly realized that coaching was not right for their relationship. "We just had this collision course," NaSheema said. They instituted a "24-hour rule," where NaSheema is not allowed to talk to Naz about basketball for 24 hours after a game.

We were like, ‘OK, you‘re invited to sit at the table now.’”

NASHEEMA ANDERSON after Naz won her high school state championship

When recruitment time came, NaSheema made Naz a binder with all of her options -- their rosters, majors, the transfer rate.

She’d been through it. She knew how it worked and what I should and shouldn’t look for, but she opened it up for me to really make that decision.”

NAZ HILLMON on her mom helping her choose a college

Naz ultimately chose Michigan, which was close enough to Cleveland that her family could come to all her home games. NaSheema sent the whole family -- sometimes up to 40 people -- itineraries, gave out car assignments and checked that everyone had their tickets.

All three women value defense, hard work and the fundamentals of the game. Gail can be heard screaming "rebound!" at Naz's games. Naz has never seen footage of her grandma playing, but Gail sees her own game in her granddaughter's hustle.

I can see the difference between how much love and support Naz got as opposed to what my mom probably got and I got. It’s so good to see [Naz doesn’t] have to fight that fight. Now they have other battles to fight.”

NASHEEMA ANDERSON on the progress of Title IX

Gail remembers being approached by a little girl at a recent Michigan game, who told her, "Because of [Naz], I'm playing ball for my school." Gail later introduced her to Naz. "I'm sure that's something that she'll never forget," Gail said.

In college, Naz has been outspoken about social justice. Last month, she was drafted by the Atlanta Dream, becoming Michigan's highest-ever WNBA draft pick.

““Am I getting the same thing as a man, or as a white woman? Am I getting the same opportunities? When we don’t have to think about that, that’s when we’ll really be in a good spot.”

NAZ HILLMON

How it started

All Marilyn Bamberger Lyke wanted was to run the full court

Growing up in the 1940s and '50s, Marilyn's favorite class at Lincoln High School in Canton, Ohio, was PE, but the classes were divided by gender and the differences between them were drastic.

The boys had freshman, JV and varsity teams in football, basketball, baseball, track and more. They played in front of sold-out crowds. The girls had no sports teams.

In her last two years of high school, girls were allowed to try out for basketball. They were divided into two six-person teams and played against each other once. They couldn't cross the halfcourt line and could only dribble twice before they had to pass or shoot.

In college, women could only play intramural except in two sports: field hockey and basketball. She loved field hockey "because I finally could run the full length. Didn't have to stop in the middle."

Marilyn got her master's in physical education at Bowling Green in the mid-60s. She remembers being the only woman in a sports administration class where a professor asked her if the school should pay for uniforms for the newly-formed girls basketball team.

"And the first thing that came to my mind was, I want to get a good job when I graduate this spring," Marilyn said. "How do I get an A in this class and answer this question and make him happy?"

How it's continued

Heather Lyke went from playing sports to running them

Heather enjoyed many sports growing up but loved the team aspect of softball. She played at Michigan for legendary coach Carol Hutchins, who she credits with fighting for equity for women.

The night before games, Heather and her teammates would wait in their dorms in case the phone rang telling them to cover the field with a tarp to protect it from rain. The next morning, they'd wait for a call to tell them to take the tarp off. "You would get in trouble if you weren't in your room," she said.

The men's baseball team had a grounds crew.

After college, Heather went to law school. She didn't plan on becoming an athletic director, but while she was in law school she reached out to Peg Bradley-Doppes, then senior associate AD at Michigan overseeing softball. She asked Bradley-Doppes how she could become like her.

She worked at the NCAA and then at Cincinnati, Ohio State and Eastern Michigan before becoming one of six women ADs in the Power 5.

As an AD charged with enforcing Title IX, Heather said she has to be "intentional" about prioritizing equity initiatives. "You have to keep it top of mind," she said.

Well thanks, I’m not a coach’s wife. I'm the athletic director.”

HEATHER LYKE to a male security guard who told her coaches' wives are not allowed on the football field

How it's going

Sophie Catalano knows how far women have come

Sophie will attend Clemson as a volleyball player this fall. She's looking forward to coming home to play against Pitt, where her mother is AD and her high school coach, Angela Seman, won two ACC championships.

Heather is proud that just two generations removed from Marilyn's experience of six-person basketball, Sophie will have the same student-athlete experience as the football team.

I think, ‘Oh my golly, were we held back!’ It is incomprehensible now. ”

It’s really about presidents giving women the opportunity. They have to see women have success. ... The more women that have success, the more opportunities.”

Since my grandma played back in the ‘50s, it’s definitely come a long way. There’s definitely a lot more opportunites ...”

““Kids today aren’t going to be quiet. ... It holds people more accountable if they realize ... you’re going to get called out on it.”

HEATHER LYKE

How it started

After the Olympics, Missy Marlowe dominated the NCAA

For Missy Marlowe, college was a way to continue her career. After competing at the 1988 Olympics, she knew she wanted to go to the University of Utah, just around the corner from where she grew up.

The gap between elite and college gymnastics was even greater in the early '90s, and it wasn't common for Olympians to compete in college.

“The skill level was much lower and the training time being limited to 20 hours a week,” Missy said, “whereas I was used to doing 25 or 30.”

Missy led Utah to two national championships. A 12-time All-American, she won five individual NCAA titles, including four at the 1992 championships. She was the first college gymnast to score a perfect 10 on all four events.

In 1992, Missy became the first gymnast to win the Honda-Broderick Cup, recognizing the top female athlete in the NCAA. "That year there were huge names that won their respective sports -- Dawn Staley was basketball, Lisa Fernandez was softball, Mia Hamm soccer," Missy said. "So that was really cool that they finally gave it to a gymnast."

Missy, center, led her team to NCAA team titles in 1990 and 1992.

In 1993, Missy received the NCAA's Top VI athlete award, one of only two women to win that year.

Missy racked up four NCAA individual titles at 1992 nationals.

Then-athletic director Chris Hill presented Missy with the 1992 WAC Female Athlete of the Year award during a Utah football game.

[We had] the best of everything at Utah. ... The work of Title IX had already been laid for me. I was the prime age to take advantage of what other people did.”

MISSY MARLOWE

How it's going

Milan Clausi followed her mom into gymnastics but found her own way

After graduation, Missy married her college sweetheart, who played football at Utah, and opened up her own gym, which became "daycare" for Milan. She coached Milan for several years, but later had to learn how not interfere too much.

I’d say, try this, try this, try that. Those were conversations for coaches. I definitely had to go through a transition period. This is not my place anymore.”

MISSY MARLOWE

Milan, on the other hand, said she craves her mom's feedback after meets now. "Of all the people I've had the privilege of working with, she's got one of the best eyes for the sport," Milan said of her mom. "The first thing I do after a meet is call her and ask for her view and what she thinks of the performances I gave."

Missy now works as a personal trainer and took a second job to help pay for trips to Milan's meets.

Milan tried the elite route for a few years but decided on college. She didn't want to follow her parents to Utah. "There would have been a lot of comparison," she said.

Nor did she want to be on an already-dominant team. “I wanted to be able to contribute to something that was still on the rise,” she said.

With Milan's help, Cal finished second at Pac-12 championships each of the past two years, and finished the 2021 regular season ranked fifth in the country, the highest ever for the program.

[My mom] had a lot more flexibility than I do. And she had this element of grace ...”

Milan has power that I never had and strength that I never had. She can do tumbling passes easily that I really struggled with.”

Milan is moving back to Salt Lake City after graduation so she can support her younger sister in her final year of high school volleyball.

““It’ll be a really cool day when an athlete is at the top of their game regardless of their gender, and they are the best that ever did it and it doesn’t matter.”

MILAN CLAUSI

Produced by ESPN Creative Studio: Jessi Dodge, Karen Frank, Jarret Gabel, Alecia Hamm, Kaitlin Marron, Beth Stojkov

Written by Elaine Teng

Photography by The Tyler Twins, Cortney White, Hana Asano, Diana King, Ed Linsmieir, Sarah Rice, Carolyn Fong

Talent production by Stacey Pressman, Lindsay Steckel and Katie Hennessey

Design by Jasmine Wiggins and Beth Stojkov. Research by Dana Lee. Hair and makeup by Yajaira Daniel, Kimberly Briggs, Simon Rihana for Art Department LA, Anna Branson for AMAX Talent Agency, Paige Ryan, Antonio Amon, Phylicia Bongiorno Kalivoda, Janet Mariscal. Additional imagery by Azzi Fudd, Brady Family, Cheryl Bridges, Heather Lyke, Hillmon Family, Marilyn Bamberger Lyke, Marsha Lake, Missy Marlowe, Shea Ralph, AP, ESPN Images, Getty, Icon Sports Media, Imagn, Pac-12 Network, Bentley Historical Library, Cal Athletics, Cleveland State Athletics, Fresno State Athletics, Georgetown University Athletics, Indiana State Athletics, Michigan Athletics, Michigan State Athletics, Otterbein University Archives, Pitt Athletics, Pitt Studios, UCLA Athletics, UNC Athletic Communications, University of Utah, Vanderbilt Athletics