His Game, His Rules

How Roger Goodell made the NFL bigger, richer, more powerful -- and now more divided -- than ever before.

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's One Day, One Game issue on newsstands March 8. SUBSCRIBE TODAY »

This story appears in ESPN The Magazine's One Day, One Game issue on newsstands March 8. SUBSCRIBE TODAY »

BEHIND THE CLOSED doors of a Capitol Hill chamber, Roger Goodell sits on a panel with an Army general before a rapt audience of two dozen lawmakers. The NFL commissioner swaps ideas with four-star Gen. Lloyd J. Austin III about how to better protect the brains of the young people who fight America's wars and play America's game. They also discuss changing the "warrior mentality" among soldiers and players, who keep fighting and playing through pain. The parallel is unmistakable: To detect and treat traumatic brain injuries, the U.S. Army and the NFL are partners in survival.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

NFL commissioner Roger Goodell met with a U.S. Army general and lawmakers to discuss brain trauma.

Military Veterans' CaucusThis was on Sept. 12 of 2012. Clad in a navy blue business suit offset by a bright yellow tie, Goodell, 54, jots notes as Austin speaks. Almost 7,000 soldiers deployed in Afghanistan have sensors embedded in their helmets to record concussive events, Austin tells Goodell. Another general muses that it's easy to imagine that someday the Army's sensors will be embedded in every NFL player's helmet.

From Capitol Hill, Goodell races to a luncheon interview at the W Hotel before a crowd of fans. The interview, initiated by the league office, is conducted by a friendly questioner from the Politico website who allows Goodell to combat a swirl of bad news, from the league's lockout of the referees to a run of negative player-safety studies. On that most important issue, he tells the awed audience, in his methodical manner of speaking: "Player health and safety is an issue that we've always been focused on. It's always been a priority."

Three years earlier, on another, more unsettling visit to Capitol Hill, Goodell was ripped by House Judiciary Committee members and former players. Repeatedly, he was pressed to acknowledge a link between playing football and cognitive erosion. Despite the fact that the league's retirement board had already made the link internally years earlier, he refused.

Goodell faces tough player-safety questions on Capitol Hill in October 2009.

Now, confronted with additional urgent player-safety questions, the polished, unflappable, confident CEO smiles and assures everyone that the NFL is transforming football into a safer, better and more exciting game.

Goodell likes to say that for the NFL and football to evolve and continue to thrive, everyone must contribute: players, coaches, officials, executives and the commissioner. But, he often reminds people, he is the commissioner, and it's his job to safeguard the game's integrity -- "protect the shield," as he puts it. And under his watch, the league has become significantly more powerful, with mushrooming revenue and global influence.

Over the past five months, ESPN has interviewed more than 80 people and obtained thousands of confidential documents for this story. (Goodell, however, declined multiple interview requests.)

The league has never been more divided. Last year's Bountygate was the latest disciplinary action to turn into a fiasco, breeding distrust of Goodell in many players. While fans lavish more attention on the league than ever before, many diehards ask whether the end is near, saying they'd never let their children play such a dangerous game. At the center of these swirling tensions is Goodell, whose decisiveness and relentlessness have come to define the NFL, for better or worse.

What's clear is that Goodell is tasked with the seemingly impossible: make the game safer for the players, more exciting for the fans and more profitable for the owners. If he has any chance of meeting those three goals, he must find a way to repair the breach between him and many players, their union and fans. At stake is no less than the future of the game, and he knows it.

SIX AND A HALF years into Goodell's tenure, his billionaire bosses believe the man who dreamed of being commissioner as a teenager is perfectly suited to lead the league through its most perilous time. They paid him $29.5 million in 2011, and in January 2012 he signed a five-year contract extension. Robert Kraft, the Patriots owner, says Goodell runs the NFL as if he owns it -- the league literally belongs to him. Jerry Jones, the Cowboys owner, says Goodell cares so much about the game that he "totally emptied his bucket -- everything he's got -- and put his life into the NFL."

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones calls Goodell a "grow-the-pie thinker" for his ability to increase revenues.

AP Photo/Mary AltafferAs part of his mission, Goodell often tells audiences a favorite story: More than a century ago, before there was an NFL, President Theodore Roosevelt saved football with the blunt force of his visionary leadership. In 1904, 18 student-athletes died playing the game, mostly from skull fractures. A devout fan, Roosevelt convened the coaches from Harvard, Yale and Princeton to a White House meeting. The innovations that were adopted -- the forward pass, the founding of the NCAA -- helped propel an endangered game into the modern era.

The history lesson not only places Goodell in Roosevelt's shoes and the current worries about player safety into a historical context, it also portends one of his greatest fears: An NFL player is going to die on the field.

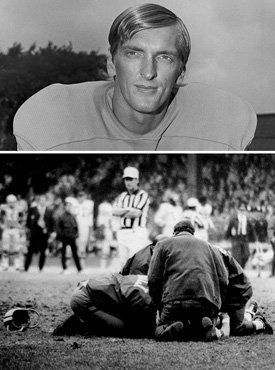

It's happened only once. Lions wide receiver Chuck Hughes died of a heart attack late in a game on Oct. 24, 1971. Within the past year, Goodell has told friends privately that he believes if the game's hard-knocks culture doesn't change, it could happen again. "He's terrified of it," says a Hall of Fame player who speaks regularly with Goodell. "It wouldn't just be a tragedy. It would be awfully bad for business."

It's a business Goodell can take much of the credit for. In 2013 the NFL will almost certainly exceed $10 billion in annual revenue for the first time, drawing closer to his goal of $25 billion by 2027 that he's shared privately with the owners. In 2014 the NFL's television contracts with CBS, NBC and Fox will increase 63 percent to an average of $3.1 billion a year. Next fall ESPN will begin paying the NFL $1.9 billion a year, up from $1.1 billion. Goodell and the league, headquartered at 345 Park Ave. in Manhattan, aggressively seize technological platforms and new markets -- its own fantasy football platform, the NFL Network and the RedZone channel, among others. Thirteen clubs are set to renovate their stadiums with $3.3 billion committed by the league and owners. Goodell has pushed expanding the regular season to 18 games and talked of adding more playoff teams, proposals that players and union leaders say is contrary to his goal of improving player safety. Says Jones, "He is what I call a grow-the-pie thinker."

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Chuck Hughes of the Detroit Lions died of a heart attack late in a game on Oct. 24, 1971.

AP PhotosAs Rooseveltian visionary, though, Goodell has struggled. Privately he is personable, down-to-earth, a good listener and a brilliant negotiator. But he also has a short fuse and can be hypersensitive to criticism of the league. He sometimes barks when asked to bend his principles, the ones he learned from his late father, a U.S. senator. He gets enraged when someone, even an owner, tarnishes the integrity of the game or challenges his judgment. Many players and union leaders talk about his failure of accountability. "Right now the league office and commissioner Goodell have little to no credibility with players," Saints quarterback Drew Brees said in December. Sixty-one percent of active players said they disapprove of the overall job Goodell is doing, according to a January USA Today poll of 300 players.

In the lengthy Bountygate scandal against the Saints, Goodell suspended four players, despite scant evidence to do so, during a period of heightened sensitivity about player safety. Last September he recognized that the referee lockout was hurting the game, but he went along with it because team owners had insisted on prolonging the standoff to its embarrassing conclusion. Both episodes became public relations disasters.

Former NFL commissioner Paul Tagliabue believes that the bitter emotions surrounding lockouts in successive years and Goodell's severe player penalties contributed to his sinking popularity. Yet he also notes that Goodell's public "style" doesn't help him. "I think Roger comes off as uncompromising," Tagliabue says, after considering his answer for a moment. "In fact, he's a good compromiser. You put him in a room with a governor, public officials and others, and he does compromise. But in public, he comes across as uncompromising."

Tagliabue mulls over the word for a moment. "He just comes across as uncompromising."

GOODELL'S UNWAVERING BELIEF in his instincts, especially about football, started young. And until recently, nothing but success came of it.

At first, all Roger Goodell wanted to do was play. The middle son of five boys, he played running back, tight end and safety until he blew out his knee at 17. After graduating from Washington & Jefferson College in 1981, he wrote to his father: "If there is one thing I want to accomplish in my life besides becoming commissioner of the NFL, it is to make you proud of me."

Charles Goodell was his idol and famous for his uncompromising politics. In 1969, as a Republican senator from New York, he introduced a bill in the Senate to withdraw all American troops from Vietnam. Charles Goodell thought too many young soldiers had died and the war had to stop. His move infuriated President Nixon and powerful Republicans on Capitol Hill. As retribution, they supported James Buckley, who won Sen. Goodell's seat in November 1970. To this day, Goodell credits his father's principles and integrity and still hangs the legislation on his office wall.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

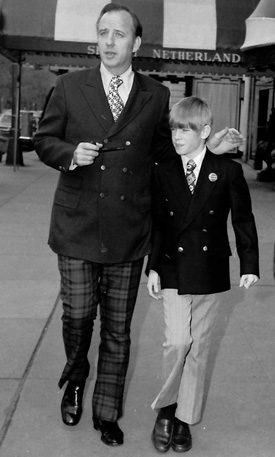

Goodell idolized his late father, Charles, a principled senator.

AP PhotoCharles Goodell's written reply to his 22-year-old son's quixotic career goal was a loving, poetic push:

Feel only your own pressure.

Your own is sufficient.

Take on the various opportunities

Calmly and collectedly.

I wish I could help more.

But now is when you are on your own

With lots of support.

Goodell began by writing letters to all 28 teams. He also sought a job -- any job -- from the NFL commissioner, Pete Rozelle. "Dear Mr. Rozelle," Goodell wrote on July 2, 1981, "I'm writing to you in reference to any job openings you may have in your offices." Over nine months, Don Weiss, the NFL's executive director, received nearly a dozen letters from Goodell beseeching him for an interview. In April of 1982, Goodell got a phone call from Weiss asking whether he was in the New York City area. Goodell was seven hours away but said yes and made it for an interview the next day. He landed an internship in the secretarial pool, clipping newspaper articles and fetching coffee for the league's public relations department.

Joe Browne, a senior adviser to the commissioner and 47-year NFL veteran, says Goodell's first break occurred when the United States Football League was founded and the new league aggressively courted potential NFL draft choices. He worked the phones and traveled, recalls Browne, "helping to recruit the John Elways, Dan Marinos and Boomer Esiasons."

During the week before the Super Bowl in New Orleans in January 1986, Goodell worked as Rozelle's driver, sleeping in the room next to the commissioner's. Up close, Goodell simply watched Rozelle, awestruck at how the consensus-builder made everything look so easy. Years later, under Tagliabue, Goodell dazzled the owners by putting more money in their pockets. He developed NFL Ventures, a separate corporation that licenses NFL-branded products and signs sponsorship and marketing agreements. As Tagliabue's right-hand man, he also helped the commissioner navigate several crises involving franchises that wanted to, or did, move. "I always felt I could trust Roger," says Ernie Accorsi, 71, the former Giants general manager who is now a league consultant. "He is genuine and honest. When he talks to you, he looks you in the eye. He listens. Roger has natural humility."

When Tagliabue, at 65, decided to step down in 2006 after 17 years as commissioner, the choice for his successor quickly became a two-horse race: Goodell and the league's chief outside lawyer, Gregg Levy. At the league meeting in Chicago, the first two votes between them went 17-14 for Goodell, but a two-thirds majority is required for election. He was the pick of the old guard of team owners, but other owners bristled that he seemed to be anointed, owners and executives say. Finally, on the fifth ballot, Goodell was chosen 23-8. Inside his room at the Renaissance, Goodell was alone, in his boxer shorts, waiting for word. When he heard a knock on the door, he quickly slipped on his pants and opened it to see Dan Rooney, the longtime owner of the Steelers.

"Hello, Commissioner," Rooney said.

Richard Mackson/USA TODAY Sports

Richard Mackson/USA TODAY Sports

IN THE BEGINNING, Goodell had the good will of the players, their union's leaders and many fans. Inside football circles, everyone knew he had prepared for this job his entire adult life. But the fans knew only what they saw. Here was a handsome Tagliabue protégé, a senator's son and a career front office guy, a glad-hander, perhaps, who looked and sounded like a politician, only with more polish. The fans could be forgiven for assuming this new commissioner might be a bit boring. Right away, he wasn't boring.

"They monetize everything. The 18-game season is a perfect example. It's a revenue-generation idea that benefits the owners on the front end because it creates more revenue. And then it benefits owners on the back end because a longer season means more injuries and fewer of our players would get into a state of vesting where owners would have to pay for their pensions. It is diabolically brilliant. It also happens to be completely inconsistent with health and safety."

- DeMaurice SmithCommissioner Goodell introduced himself as a no-nonsense disciplinarian, toughening the personal-conduct rules in 2007 to enforce harsh punishment for off-the-field misbehavior by any player, coach or executive. Unlike Tagliabue, Goodell dealt out lengthy suspensions to players like Adam "Pacman" Jones (personal conduct; 2007 season), Michael Vick (dogfighting; 2007-08) and Ben Roethlisberger (personal conduct; four games in 2010).

But in 2007, after Patriots coach Bill Belichick and his assistant coaches were caught using a secret videotaping system of opponents, Goodell led a confounding investigation. He decided on the punishment in five days and shut down the case. He fined Belichick $500,000 and the team $250,000 and stripped New England of a first-round draft choice. Then Goodell ordered the videotapes destroyed. The decision ensured that the question about how much the spying had helped the Patriots win games, including Super Bowls in the 2001, 2003 and 2004 seasons, would likely forever remain a mystery.

The questions left unresolved by the truncated inquiry persist: Did Goodell destroy the evidence to save the Patriots and the league from breathtaking embarrassment? During last season's playoffs, the scandal was raised again, this time by Ravens linebacker Terrell Suggs, who pointed out that the Patriots have not won a title since they stopped videotaping opponents.

Yet Kraft was livid at Goodell's punishment. "He really was much too tough on us," Kraft says. "He did what he thought was right for the league, and that's what I want him to do even if it goes in the short term against the best interest of the Patriots. I want him to represent what's in the league's best interest, even if his judgment isn't pure."

Goodell seemed to relish the role of a tough-as-nails prosecutor and judge. Word quickly ricocheted around the NFL's executive suites: Don't lie; he won't tolerate it. When a player or his lawyer asked Goodell for leniency behind a closed door, he'd bristle or even bark, refusing to be told how to best protect the shield. Even his bosses acknowledge Goodell's hot decision-making temperament.

Several years ago, after an NFL assistant coach was stopped by police on suspicion of driving under the influence, the coach and his lawyer were at NFL headquarters sitting across a conference-room table from Goodell. The commissioner was prepared to conclude that the coach's DUI arrest was "conduct detrimental" to the league.

Peter Ginsberg, the coach's lawyer, told Goodell the coach had an unblemished record through two decades in the league as a coach and a player. He was embarrassed and devastated by the DUI arrest, which was knocked down to reckless driving, and Ginsberg asked Goodell to look at the situation with some compassion.

Goodell suddenly stood up. "He turned bright red," Ginsberg recalls, "and screamed at me that I should not lecture him about what was right and wrong." Then Goodell walked out of the room. (A league source says Goodell only raised his voice.) The coach was fined and suspended.

"This man can bite," says Jerry Jones, whose team circumvented the owners' unwritten pact to go slow on player deals in preparation for the 2011 lockout and was penalized $10 million in salary-cap space by Goodell. He, Kraft and John Mara, the owner of the Giants, all say Goodell possesses a quick-trigger temper.

"He'll flare," Jones says. "He's emotional, but I happen to like that. I think he's courageous. I think he has a big set of them. I think he's willing to step up and take the heat and take the risks. And he's willing to take the consequences."

ONE CONSEQUENCE OF Goodell's discipline has been growing player distrust. "It's like a dictatorship," Falcons wide receiver Roddy White told ESPN. "Whatever he says, that's the end of it." Though the commissioner delegates on-field infractions and drug issues to others, the ire for all penalties is still reserved for him, a mistrust that one NFL source says the union leadership "foments."

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

DeMaurice Smith, leader of the NFLPA, and Goodell have a strained relationship that has deteriorated in recent months.

Kevin Lamarque/ReutersThe chasm grew in 2010 when Goodell hit the road on a listening tour of 10 training camps. The owners had already indicated they would lock out the players after that season, and Goodell wanted to hear their concerns. But at one meeting with the Colts, the players' rancor toward Goodell became so raucous that player rep Jeff Saturday cut it short and escorted Goodell from the locker room. "What offended them is that he told them he was neutral and he actually thought they'd believe it," says DeMaurice Smith, a former federal prosecutor who had taken over the year before as head of the NFL Players Association. He and Goodell have a strained relationship that has deteriorated over time. "That was the beginning -- it has led us to a lack of credibility from the players to Roger, and the NFL."

Rozelle was able to avoid angry union disputes because he had a separate management council that negotiated collective bargaining agreements with the players. Tagliabue, some owners and executives privately say, gave far too much to the players. So it fell to Goodell to push the pendulum back.

As the league locked out the players in early 2011, Goodell endured months of battering on Twitter, Facebook and message boards. Publicly, he took the heat in stride, telling interviewers that he understood the fans' criticism because "they just want football and so do we." Without having to cancel a single regular-season game, Goodell and Smith negotiated a new collective bargaining agreement stretching forward a decade. "It was an exhausting, draining process," Kraft recalls. "His leadership was really off the chart."

Some players have complained that the union did not deliver the best agreement. The most persistent complaint is that Goodell's absolute power to determine "conduct detrimental" had remained largely intact.

Among the owners, the collective bargaining agreement stands as Goodell's greatest accomplishment. The deal is that good. "I think Roger has done better than any of us could have wished for," Kraft says.

Even DeMaurice Smith is in awe of the commissioner's business acumen. "When it comes to that stuff, he's brilliant," Smith says. "They monetize everything. The 18-game season is a perfect example. It's a revenue-generation idea that benefits the owners on the front end because it creates more revenue. And then it benefits owners on the back end because a longer season means more injuries and fewer of our players would get into a state of vesting where owners would have to pay for their pensions. It is diabolically brilliant. It also happens to be completely inconsistent with health and safety."

DEPENDING ON WHO is talking, Goodell's motives when dealing with the health and safety crisis have ranged from heartfelt to heartless. "Player safety is Roger's No. 1 priority," Mara says. "It's something, quite frankly, that he wants as part of his legacy as a commissioner." Jones says simply, "Roger is the best qualified person that I know in this country to do something about player safety."

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Robert Kraft, Jerry Jones, John Mara and the rest of the league's owners are extremely pleased with Goodell's job performance. They paid him $29.5 million in 2011.

AP Photo/Alex BrandonCounters Ginsberg, who has much experience defending players before Goodell: "Based on my experience, the commissioner … doesn't view individual players as anything more than commodities for the business."

Yet Goodell's hard-to-read or mixed motives do not change the reality that the crisis threatens the league's reputation and finances. More than 4,000 ex-players -- one-third of all living retired players -- are suing for billions of dollars on the grounds the NFL "deliberately ignored and actively concealed" information about concussions for decades. The Fitch credit-rating agency recently reported that the lawsuit added uncertainty to the league's future finances.

The league did not formally concede that concussions could have lasting effects until December 2009, two months after Goodell wouldn't acknowledge it before Congress. "The problem of head trauma and long-term neurological damage -- it was deny and obfuscate and block in any way possible that this was going on," says Eleanor Perfetto, a leading player-safety advocate and the widow of Ralph Wenzel, a guard for the Steelers and Chargers who suffered from dementia and died in June at 69. At a meeting of ex-players and Goodell in December 2008 in Bethesda, Md., Perfetto -- her husband's legal guardian -- showed up unannounced to have her voice heard. Her husband could not attend. Goodell did not allow Perfetto inside the meeting room, saying it was a session only for retired players. She told the commissioner: There are many not healthy enough to attend these important meetings. "Who speaks for them?"

"I don't do things for public relations. I do things because they're the right thing to do, because I love the game."

- Goodell to Time in NovemberIn time Goodell and the league agreed to establish a pool of money for players who retired before 1993 called the Legacy Fund: $620 million from the league and players. John Mara, the Giants owner, says Goodell recognizes that the league has made great strides to help retired players but says, "Frankly, we have not done enough. And Roger is well aware of that."

On the safety of current players, the owners and current and former league executives say Goodell and the league have made tremendous strides, such as changing kickoffs from the 30- to the 35-yard line. Goodell is updating the league's injury protocols and has pledged to add neurosurgeons to game-day medical teams. The league plans to expand season-ending physicals into a three-day "physical, mental and life-skills" review, the commissioner has said. The league also has partnered with GE to develop better technology to detect concussions.

But some former and current players say Goodell's changes are motivated in part by the lawsuit. To be sure, the threat is real enough that two sources with knowledge of the discussions say there's a deep split among owners: Some are open to settling the case.

But the key question is one Goodell sidestepped as recently as Super Bowl Sunday on "Face the Nation." "Do you now acknowledge," CBS's Bob Schieffer asked, "a link between the game and these concussions that people have been getting, some of these brain injuries?"

Goodell responded: "That's why we're investing in the research, so that we can answer the question: What is the link? What causes some of the injuries that our players are still dealing with?" Pressed by Schieffer, he said: "Well, Bob, again, we're going to let the medical individuals make those points. We are going to give them the money, advance that science."

Goodell has also appeared to try to manage how the health issue is portrayed. This past September, on the same day a study was released showing that NFL players are four times more likely than the U.S. general population to die from Alzheimer's or ALS, Goodell announced on NBC that the league was making a $30 million grant to the National Institutes of Health for brain-injury research.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

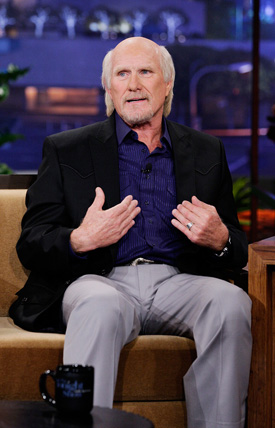

Goodell and the league office were furious with Terry Bradshaw after the Hall of Famer made disparaging remarks about the league's motives on player safety on "The Tonight Show with Jay Leno."

Paul Drinkwater/NBC/Getty Images"I don't do things for public relations," Goodell told Time magazine in November. "I do things because they're the right thing to do, because I love the game." Behind the scenes, Goodell and league executives closely monitor reports by the NFL's broadcast partners. With increasing regularity, what they see angers Goodell and league execs, sources say.

Hall of Fame QB Terry Bradshaw was a guest on "The Tonight Show With Jay Leno." Bradshaw said any effort by the NFL to demonstrate concern for the health and well-being of former players is driven mainly by worries about the litigation and the public relations impact. "They're forced to care now because it's politically correct to care," Bradshaw told Leno. "Lawsuits make you care. I think the PR makes you care." When Goodell heard Bradshaw's comments, he "went ballistic," one source said. A video clip of Bradshaw's comments appeared on "The Tonight Show's" website, but his NFL remarks were not included.

In September the NBC Sports Network planned to run a piece produced by Sports Illustrated about spouses and caregivers of retired players. But in an email written a week before the piece was to air, a person involved in the production told a colleague "the NFL went nuclear and was trying to get it killed." Sources at both the NFL and NBC say they were not aware of any contact between them about the story. Ultimately, say SI and NBC, they had a disagreement about whether the piece should air. It never did.

The perception that Goodell will go to great lengths to control how the league is portrayed has become one more barrier between him and former and current players -- even when it's false. In July Hall of Fame defensive end Bruce Smith taped a promo video to run during the premiere of ESPN's "Monday Night Football." Three days after shooting it, he joined the concussion lawsuit. When the video aired and he wasn't in it, Smith called Goodell the next morning to angrily ask whether the commissioner had pressured the network to edit him out. Goodell insisted that wasn't the case. (Months later, in fact, during the Super Bowl, the NFL aired an ad about the league's future evolution that featured three players who are plaintiffs in the lawsuit.) In September ESPN reached out to Smith to explain he'd been cut solely for creative reasons. "The NFL never expressed any issue with his participation," says ESPN PR representative Josh Krulewitz. Goodell then offered Smith a trip to London for the NFL's game in October as a peace offering, a source said.

GIVEN THE NFL'S private ownership and Goodell's high volume on issues, it's hard to know when the owners, rather than the commissioner, are behind a controversial action. Such was the case when criticism of Goodell reached its highest pitch during the referees lockout in September.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Last September's referees lockout and the league's use of replacement officials became a public relations disaster for Goodell and team owners.

Otto Greule Jr./Getty ImagesFor a commissioner so meticulous about the league's reputation on safety, not to mention management of its brand, the fight with the referees was oddly tin-eared.

After Week 1, the commissioner gave high marks to the replacement referees, telling Politico, "These guys did an outstanding job … They are going to get better." But they got worse, much worse. A replacement referee infamously blew the call on a final-play Hail Mary pass that transferred a Packers win to the Seahawks. DeMaurice Smith, the union leader, was so angry afterward that he drafted a grievance against the NFL for intentionally jeopardizing the players' safety with replacement referees. It wasn't necessary. Within 72 hours, with Goodell working around the clock, a labor agreement was signed, and the permanent officials returned to the field.

The fight with the referees was one Goodell had wanted to abandon, several owners and executives say. A handful of owners stubbornly objected to paying pensions to part-time referees. "The criticism ought to go to us," says Mara, the Giants owner. "Roger wasn't doing anything ownership didn't want."

From his perspective, Smith says the referees lockout revealed a telling dynamic, at least on bottom-line issues. "They have a commissioner who is far more restrained in his ability to do things he thinks are right," Smith says. "Roger is truly one of the smartest, brightest executives I've ever met. I have a hard time believing he didn't understand the significance of the referee lockout on the image of the league and the perception that it isn't taking good care of the players. He had to do what his bosses wanted."

The Bountygate investigation was a quagmire almost entirely of Goodell's making.

IF THE REFEREE fiasco had Goodell trapped in a vise created by his bosses, unwilling or unable to act, the Bountygate investigation was a quagmire almost entirely of Goodell's making.

One of Goodell's motivations to take a resounding stand on Bountygate seems obvious: He was protecting the shield. But it's also clear he reacted to being lied to. The league first got wind of a possible Saints bounty program in 2010 from another team's coach. When investigators interviewed Saints defensive coach Gregg Williams and player Anthony Hargrove, however, both denied its existence, allowing it to continue unabated for another two seasons until it was exposed.

The details also infuriated Goodell. The league had long issued annual written warnings to all the clubs that pay-for-harm programs would not be tolerated. Yet Saints players, as he saw it, enthusiastically agreed to try to hurt opposing players. "Deeply offended," Mara says of Goodell's reaction, which led to Goodell's unprecedented suspensions of the Saints general manager, head coach and two assistants last March.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Two former New Orleans Saints players say Remi Ayodele, right, is the player who made a statement that Goodell presented as evidence that turned teammate Anthony Hargrove into a high-profile villain of Bountygate.

Ronald Martinez/Getty ImagesAt the time, he charged that as many as 27 Saints defenders had participated in the program. But two months later, in May, based largely on the testimony of Williams and former coach Mike Cerullo, plus evidence culled from Saints computers, he suspended Hargrove and three leaders of the defense, Jonathan Vilma, Will Smith and Scott Fujita. In the parlance of prosecutors, it appears Williams "flipped" on the players with hopes of later winning leniency from Goodell.

ESPN has exclusively obtained Bountygate documents including confidential transcripts of the private four-day appeal hearing held by former commissioner Tagliabue late last year. The documents show an investigation remarkable for its limited scope -- only one Saints player spoke to investigators, for example -- and for damning accusations that league officials quietly retracted in later memos or chose not to introduce as evidence.

Former U.S. Attorney Mary Jo White, hired by the NFL to review Bountygate evidence, told reporters that Vilma held up $5,000 in each hand the night before a 2009 playoff game against Arizona, saying the cash was a bounty on Cardinals QB Kurt Warner. Yet the league did not introduce the evidence during the appeal hearing.

League officials also invited 12 members of the media to review a videotape of the 2009 Saints-Vikings NFC championship. This was the game when a $10,000 bounty had allegedly been placed on Vikings QB Brett Favre, who got knocked down hard by Saints players Remi Ayodele and Bobby McCray (though no flag was thrown), after which a sideline camera caught a Saints player saying to McCray, "Bobby, give me my money." On the videotape, the league had added a caption attributing the words to Hargrove, who hadn't been in on the hit.

White told the reporters the video was undeniable proof showing that Hargrove "smiles and winks and states, 'Bobby, give me my money.'"

"There were two victims -- the four players and the commissioner."

- Paul Tagliabue on Bountygate"How do you know it's Hargrove's voice?" a reporter asked.

"Because you can see his lips moving," White said. That night ESPN and other media outlets repeated that Hargrove had said the words, turning him into a public villain of the scandal.

But you cannot see Hargrove say "give me the money." At that moment, as he sits on the bench, his head is blocked from view by the back of Ayodele.

Hargrove angrily denied the accusation then, and he still angrily denies it. His agent obtained a voice analysis that shows it was "unlikely" the voice was Hargrove's. "It was Remi," Hargrove told ESPN recently. "Everyone knows it." Earl Heyman, a former Saints practice squad member who was on the sideline, agrees it was Ayodele.

Ayodele, who was not questioned about the incident by the NFL or suspended, declined to comment for this story. But on Sunday, he tweeted at Hargrove: "get real kid ur done I said NOTHING nobody on the team did I'm still trying to figure out this bounty what's he talking bout?"

Heyman tells the Mag, "I think that the NFL was out for blood, that Roger Goodell said, 'Hey, this is my story, I'm sticking to it.'"

Quietly, a few weeks later, Goodell backtracked from the Hargrove allegation in a Bountygate memo. "I am prepared to assume" -- contrary to what he had told the public -- "that he did not make it [the comment]," Goodell wrote. But the charge had stuck.

During the players' four-day appeal, it was clear Tagliabue felt himself wrestling with a muddled case that included witnesses often contradicting each other and even themselves. The players' lawyers became convinced he was protecting Goodell, who had appointed him despite objections that Tagliabue's law firm represents both the league and Goodell. The lawyers complained that the NFL and Tagliabue gave them only a few documents: 184 out of 18,000 requested before the appeal. After the hearings, the players and their lawyers said they were certain Tagliabue would rubber-stamp Goodell's penalties.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Hargrove says a sloppy and unfair Bountygate investigation cost him his livelihood.

AP Photo/John MinchilloInstead, Tagliabue surprised nearly everyone by vacating the punishments of all four players. In his 22-page decision, he said he was persuaded that Goodell should not have punished the players for doing what their coaches told them to do. And his ruling strongly suggested Goodell had impatiently and incorrectly tried to change the culture of the game through the punishments.

In a wide-ranging interview with ESPN, Tagliabue amplified his feelings, saying aspects of the NFL investigation were "unfortunate." "Sometimes," he says, "the best way to get strict enforcement is to start off like a tortoise and move more slowly and eventually you are moving like a hare, as opposed to starting off like a hare and generating a lot of push-back."

Yet he also went out of his way to call some criticism of Goodell's role in Bountygate unfair.

"There were two victims -- the four players and the commissioner," Tagliabue says. Goodell was "a victim of obstruction by coaches" and the players' wearying appeal tactics. He added that the controversy "had to end" because it was "overshadowing everything Roger had accomplished in emphasizing player safety. It is easy to have the wisdom of hindsight. It's not fair to Roger."

After Tagliabue overturned the player suspensions, it was "time to move on," the commissioner said.

Williams has. In February Goodell reinstated him, and this fall he will be a senior defensive coach for the Titans.

But Hargrove can't. He hasn't been signed by anyone since the suspension was vacated. And Goodell won't forgive him for denying the existence of bounties to an NFL investigator back in 2010. Last April Hargrove submitted a declaration explaining he'd done it because Williams had instructed him to, but Goodell was unmoved.

"The way this thing has unfolded, I was an easy target," says Hargrove, who is now living in the basement of his agent Phil Williams' house in an Atlanta suburb. "It's easier to go against a guy who's been known for not always doing things the right way." In 2008 Hargrove had missed a season for failing a drug test.

ENLARGE

ENLARGE

Fans have taken aim at Goodell over Spygate, Bountygate, two lockouts and player discipline.

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert"How am I supposed to move on?" Hargrove continues. "This was the ending of the world for me. I lost a whole year of football. I lost money for my 401(k). I lost severance. I lost a great deal because of the lack of professionalism. Because they say, 'Hey, move on,' we're supposed to be fine with it? No. I don't think so."

Hargrove thinks for a moment, then adds, "If anyone's been conduct detrimental, it's Roger Goodell."

ROGER GOODELL IS back in New Orleans. At his state-of-the-league news conference on the Friday before the Super Bowl, the commissioner says everyone in the Big Easy has treated him wonderfully, despite the past year. He acknowledges that on the walls of more than a few restaurants and bars are "Don't serve this man" fliers with his picture. "I had a float in the Mardi Gras parade," he says, deadpan, from the podium. "We got a voodoo doll." Sitting a few rows away are Goodell's bosses, including Kraft, Mara, Jones and Arthur Blank, the owner of the Falcons. They're laughing.

Goodell is asked whether he harbors any regrets about Bountygate. He says he regrets not explaining "clearly enough" that it is "the collective responsibility" of everyone in the NFL, including the players, to try to make the game safer. "That is something we are going to be incredibly relentless on," he says.

Even after the Bountygate debacle and the referees lockout, Goodell has put the league on notice: He's going to continue to be relentless. Incredibly relentless.

A reporter asks the commissioner whether "trust had been fractured" between him and the players. The question is again framed around Bountygate, though it could apply to any number of unresolved hot-button issues, from the union's desire for tougher health and safety standards to the league's desire to begin HGH testing this fall. Goodell is still in favor of adding regular-season or playoff games. "I believe that we're all responsible for what goes on in our locker rooms, on the field, as part of our game," Goodell says.

Finally, Goodell acknowledges that after a difficult year, he's taken a hard look at himself. Now is when you are on your own, his father wrote him three decades ago, with lots of support. To tackle the great challenges that lie ahead, how will Goodell secure the support he'll need from everyone in the NFL, including players? "I'm going to have to work harder to try to make sure we can work together, we can trust one another," he says. "But we also need to make sure that we understand that we're going to have differences, and that's OK."

Just as the game of football, if it's going to survive, must evolve, Roger Goodell now knows, so, too, must the commissioner.

AP Photo/David Goldman

AP Photo/David Goldman

Don Van Natta Jr. is a senior writer for ESPN.com and ESPN The Magazine. He can be reached at don.vannatta@espn.com. Follow him on Twitter at @DVNJr.

Follow ESPN_Reader on Twitter: @ESPN_Reader. Follow the Mag on Twitter: @ESPNmag

Join the conversation about "His Game, His Rules."