When Jerome Holtzman, a legendary baseball writer and a good man, died two weeks ago, I hoped some closer would celebrate a save by pumping his fist, falling to his knees, pointing to the sky and shouting, "This one is for you, Jerome!"

The gesture would make me respect closers a little more. Which is to say, still not very much.

The problem is that Holtzman's well-intentioned attempt to measure a reliever's worth has been cheapened, manipulated and bastardized to the point that the save is the most overrated stat in baseball and the closer is the most overrated and replaceable role in American sports.

We have hyped the closer into a ridiculously over-the-top role. They enter games to fanfare normally reserved for Oprah and pro wrestlers -- heavy metal entrance music is such a clichéd prerequisite that controversies arise over who has the more legitimate claim to a particular song (see Mariano Rivera v. Billy Wagner). When J.J. Putz still was regularly closing games for Seattle, the Mariners played AC/DC's "Thunderstruck" over the loudspeakers while the scoreboard flashed menacing lightning graphics and displayed the current time as "10:03 PDT, Putz Domination Time."

G Fiume/Getty Images

Francisco Rodriguez is racking up the saves but hasn't entered a game before the ninth inning or with a runner on base all season.

With the American League's worst record, sadly, the Mariners have been unfortunately stuck on stubborn old Pacific Daylight Time this season.

The save is the only situation in which a manager makes his decisions based on a statistic rather than what makes the most competitive sense for his team. The only comparable is when a manager stays with a struggling starter with a big lead so he can get through the fifth inning and qualify for a win, but this occurs rarely. Managers, however, routinely bring in their closers just because it is a "save situation" rather than a situation in which the opponent is truly threatening. It's ridiculous. Managers feel the need to please their closers -- and their closer's agents -- by getting them cheap saves to pad their stats and their bank accounts.

I asked Red Sox closer Jonathan Papelbon whether the definition for save situations could be improved, and he said no. "A save is what it is. You save the game. It's a situation in which the tying run is at the plate or on deck and the game is on the line."

Well, that's precisely the problem: the very name. "Save" is as misleading a term as "reality television." Closers don't really "save" many games these days, nor is the game really on the line most of the time. Closers merely conclude what is usually a foregone conclusion. By the time the music starts and they charge to the mound to protect a three-run lead, the victory is already all but assured.

Don't believe me? Check out this study by Dave Smith of Retrosheet. He researched late-inning leads over 73 seasons, from 1944 to 2003, and an additional 14 seasons prior to that span. What he found is that the winning percentage for teams who enter the ninth inning with a lead has remained virtually unchanged over the decades. Regardless of the pitching strategy, teams entering the ninth inning with a lead win roughly 95 percent of the time. That was the exact rate in 1901 and that was the rate 100 seasons later. In fact, the rate has varied merely from a high of 96.7 percent in 1909 to a low of 92.5 percent in 1941.

But I know what you're thinking. That study applies to all leads, including big ones. But what about the slim leads, the ones defined as "save situations"? Glad you asked. Because Smith looked at those leads as well. And what he found is winning rates for those leads have also remained constant -- one-run leads after eight innings have been won roughly 85 percent of the time, two-run leads 94 percent of the time and three-run leads about 96 percent of the time.

FINDING A CLOSER

1991: Juan Berenguer (17 saves, 2.24 ERA)

1992: Alejandro Pena (15 saves, 4.07 ERA)

1993: Mike Stanton (27 saves, 4.67 ERA) and Greg McMichael (19 saves, 2.06 ERA)

1994: Greg McMichael (19 saves, 3.84 ERA)

1995: Mark Wohlers (25 saves, 2.09 ERA

1996: Mark Wohlers (39 saves, 3.03 ERA)

1997: Mark Wohlers (33 saves, 3.50 ERA)

1998: Kerry Lightenberg (30 saves, 2.71 ERA)

1999: John Rocker (38 saves, 2.49 ERA)

2000: John Rocker (24 saves, 2.89 ERA)

2001: John Rocker (19 saves, 3.09 ERA) and John Smoltz (10 saves, 3.36 ERA)

2002: John Smoltz (55 saves, 3.25 ERA)

2003: John Smoltz (45 saves, 1.12 ERA)

2004: John Smoltz (44 saves, 2.76 ERA)

2005: Chris Reitsma (15 saves, 3.93 ERA) and Kyle Farnsworth (10 saves, 1.98 ERA)

Don't get me wrong. I realize some pitchers are obviously better than others. And I would rather have six-time All-Star Billy Wagner on the mound for my team in a key situation than, say, Aaron Heilman. The Mets, however, would not. Consider last Tuesday's game against the Marlins. New York led by three runs in the ninth inning, a textbook example of the cheap save. Naturally, manager Jerry Manuel brought in Wagner even though that is a situation a team almost always wins. But two games later when the Mets and Astros were tied 3-3 with one out and the bases loaded in the eighth -- i.e, a late-inning situation in which the game's outcome was completely in doubt -- Manuel kept Heilman on the mound. Two pitches and one grand slam later, the Mets trailed 7-3 and the game was effectively over.

Why do teams do this when this is such a readily apparent poor use of resources?

"I'll tell you why," Oakland general manager Billy Beane says. "It's the same reason more football coaches don't go for it on fourth-and-1. Because when it doesn't work, 30 of you guys come storming in wondering why the manager didn't go to the closer. It's turned into a situation where a lot of emotion is tied to that decision, just as a lot of emotion is tied to the fourth-down decision. Even if you know the odds, it's more comfortable being wrong when you go to the closer or the punter.

"The position has become very media-driven. It became a national story when Boston announced it would go with a bullpen by committee."

Guilty as charged. Based on the Boston media's reaction, you would have thought Mike Timlin was dating Gisele Bündchen and Madonna at the same time, particularly when the brief experiment in 2005 didn't work out as planned. But as Beane says, that's only evidence that the Red Sox didn't have the proper relievers in place, not that a closer by committee doesn't work.

"Whitey Herzog had a lot of success with a closer by committee," Beane says. "Although now that I think back on it, I'm not sure they called it 'closer by committee' back then. I think then it was just called 'using your bullpen wisely.' Then closers became 'specialists.'"

Indeed. And the situation really started getting out of hand when relievers became "closers."

Goose Gossage, newly enshrined in the Hall of Fame, pitched when relievers actually worked for a living and were called firemen, not closers. Back then, a team's relief ace came to the rescue when needed, regardless of the inning. They didn't need a "save situation." If the alarm bells were ringing, smoke was filling the stadium and mothers were ready to toss their babies from the upper deck, they raced to the mound. No wonder they needed bullpen carts back then -- they were in such a hurry to douse the flames, they should have had Dalmations riding with them. Contrast that with today's closers who show up to claim credit with the reporters after the set-up men already have the flames under control. Some don't even go to the bullpen until the seventh inning. Lee Smith, who somehow received more Hall of Fame votes than Jack Morris in January, was said to nap in the trainer's room until needed.

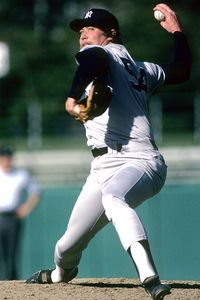

Focus on Sport/Getty Images

When relievers were men: Goose Gossage topped 130 innings pitched three times as a reliever.

As Jayson Stark points out in "The Stark Truth," in Goose's first season as a closer he recorded at least 10 outs in 17 different games, including three outings of seven innings or more. Yes, seven innings. If a manager tried using a closer for that many innings today, the reliever, his agent, the Players Association and the Teamsters would file an injunction before his 20th pitch.

AGENT: Your honor, the manager wants my client to pitch in a nonsave situation!

JUDGE: The sadist! Lock him up!

In a story for Baseball Digest explaining how he came up with the save, Holtzman wrote that former manager Johnny Oates told him, "You changed the game. You created the ninth-inning pitcher." Holtzman replied that it "was the managers who did it, not me. Instead of bringing in their best reliever when the game was on the line, in the seventh or eighth inning, which had been the practice in the past, they saved him for the ninth."

Like the development of ever-larger, more dangerous SUVs with increasingly poor mileage, today's closer role evolved over time from an idea that made good sense in certain situations until it became the bloated, ubiquitous, unwieldy and inefficient beast it is today.

The restricted role of closers not only is an inefficient use of their talent, it renders them useless during a prolonged losing streak because the team never has a lead in the ninth inning to protect. Putz "saved" 40 games last year with a 1.38 ERA, was named the team's best pitcher by the local writers and the reliever of the year by the league. Yet when Seattle was in the midst of losing 13 of 14 games in late August and early September to tumble from the wild-card lead to hopelessly out of playoff contention, Putz pitched only twice. So when the team was floundering at a make-or-break point of the season, its supposed best pitcher -- the league's alleged best reliever -- was of no help because the Mariners were not in official and proper "save situations."

To not use your best pitcher for almost two weeks when the season is going down the drain because the stars were not properly aligned? I'm sorry but that's just messed up.

I will grant you, a one-run lead today is a more precarious margin than a one-run lead in 1968, when scoring was much lower. And perhaps in an age when starters barely go six innings, the use of closers has helped teams maintain that historically high winning percentage when leading after eight innings. But it's also true they would be much more valuable pitching earlier if the game is on the line.

FINDING A CLOSER

Chicken or the egg? Nature or nurture? As you are aware, Angels closer Francisco Rodriguez is very much in line to wrest the single-season saves record of 57 from Bobby Thigpen. As you may also know, the Angels have been winning well above their station based on their runs scored and runs allowed. In fact, they're about nine games ahead of where they should be.It is not uncommon for pitchers with huge saves totals to play for teams that overachieve. Here is every pitcher who reached 50 saves along with the plus/minus for their team's Pythagorean wins (note: there are no minuses).

+7: Bobby Thigpen, 1990 White Sox; 57 saves

+2: Eric Gagne, 2003 Dodgers; 55

+5: John Smoltz, 2002 Braves; 55

+5: Trevor Hoffman, 1998 Padres; 53

+3: Randy Myers, 1993 Cubs; 53

+12: Mariano Rivera, 2004 Yankees; 53

+2: Eric Gagne, 2002 Dodgers; 52

+5: Rod Beck, 1998 Cubs; 51

+7: Dennis Eckersley, 1992 A's; 51

+6: Mariano Rivera, 2001 Yankees; 50

That's an average of 5.4 wins over expectations. So, here's the question for you to ponder: Did these teams overachieve because they had a reliable closer piling up saves, or was the closer able to pile up saves due to the nature of the team's overachievement?

--Jim Baker

That's because regardless of era, all stats point to this truth: The key is not who you have on the mound in the ninth but getting to the ninth with a lead.

People often talk about how pitchers need the proper mentality required to be a closer. While it is true that you must be able to let a blown save roll off your back, it is equally true that you need the proper mentality to be a starter so you can handle a bad start and the inability to do anything about it for another five days. All roles in baseball require you to handle adversity and failure. To single out the closer role as somehow more difficult only makes it seem more stressful than it should be.

Yes, teams need to know they can rely on someone to take the mound in the ninth and close out the game. But such pitchers are more numerous than "CSI" series.

The job of protecting ninth-inning leads that history shows are almost always successfully protected is simply is not as hard as people make it to be. Time and time again we see pitchers who struggled as starters become unhittable closers (Mariano Rivera, Eric Gagne, Joe Nathan and Jonathan Papelbon are recent examples), and yet we still pretend the job is so difficult, demanding and onerous that you need the pitching talent of Sandy Koufax, the philosophical makeup of the Dalai Lama and the courage of Rosa Parks.

Again, look at the Mariners. They once traded Jason Varitek and Derek Lowe for Heathcliff Slocumb out of desire to get a "proven" closer for the stretch run. That was a disastrous deal. And as the team has shown over the past nine seasons, completely unnecessary. In 2000, the Mariners signed Kazuhiro Sasaki, who was a reliable closer for three seasons. When he got hurt in 2003, they went to Shigetoshi Hasegawa, who was better. They replaced Hasegawa and Sasaki with Eddie Guardado, who was just about as effective. Then they replaced him with Putz, who was even better. And when Putz got hurt this season, they subbed for him with Brandon Morrow, who has been just as good. And they also traded away George Sherrill, who has 30 saves for the Orioles.

That's five consecutive relievers who have all been highly effective closers. Some were high-priced free agents. Others were inexpensive middle relievers who got promoted. The point is, not only were the Mariners able to continually find a closer, they even had potential closers to trade away.

It's ridiculous. As the role has become increasingly limited, dominating performances have piled up. Relievers have had 30 saves, an ERA under 2.00 and a WHIP (walks plus hits to innings pitched) of less than 1.00 on 33 occasions, yet 15 of those times have been in the past five years -- and six closers could do it this year alone. Is that because these closers are somehow better than their predecessors or because they have been used in such rarified situations that they are able to dominate for three outs?

With 45 saves already, fans are wondering whether Frankie Rodriguez can break Bobby Thigpen's single-season record of 57. The answer is yes, of course, he can, especially if roughly two-thirds of his save opportunities continue to come with a two-run or more lead. K-Rod has yet to appear before the ninth inning.

The current overemphasis on closers developed over years and will not disappear overnight. In this age of 24/7 sports networks and blogs, few teams will risk bucking what has become conventional wisdom by reverting overnight to previous relief strategies. One blown save and the phone lines to the local sports talk show will be tied up for three weeks with irate fans demanding the manager be fired.

"Having lived both sides of it, a closer doesn't seems so important until you don't have one," Beane says. "I know that sounds contradictory but a lot of emotions are tied in with the game. If there's a three-run lead in the ninth and the stats show that you win 97 percent of those games and you're upgrading to only 98 percent with your closer, well, that 1 percent increase is worth it because losing is so painful in that situation."

Teams would have to slowly wean themselves off the all-powerful closer, gradually bringing their best reliever into earlier, more important situations. And the media will have to start hounding managers with questions like, "Why did you use your closer with a three-run lead in the ninth when studies show you would have probably won anyway? Why not save him for a more important situation, such as a tie in the seventh?" But some team eventually will come to its senses and do exactly that. And as opponents see this strategy work over the course of months and years -- and see that it also was a cheaper way to win games -- more teams will copy until it becomes the preferred method. They will, as Beane says, "stumble back onto the old system" and realize that if it was "good enough for Whitey Herzog, it's good enough for us."

If so, sanity -- rather than the "save situation" -- will rule the day again.

Of course, there is one inherent risk to that. While teams and fans would view the save, "save situations" and closers in a more accurate light, there is also the unfortunate risk that they would eventually overvalue the "hold."

•

•

Comments

You must be signed in to post a comment