It is one of the most tried-and-true tactics in (American) football: beat 'em down with the short stuff -- a good run game, a good, quick passing attack -- and when the deepest defenders are leaning in the wrong direction, hit 'em deep on the play-action bomb.

- Stream ESPN FC Daily on ESPN+ (U.S. only)

- Don't have ESPN? Get instant access

In a way, you could say that the play-action bomb has saved Real Madrid's season, but we'll get to that.

Beating your opponents by playing off of your own tendencies is a common and often deadly tactic in any sport, of course, but it was still a bit jarring -- and exhilarating -- to see maybe the two most impactful goals in the quarterfinals of both the Champions League and Europa League produced by long balls.

In the latter, Manchester United cracked open a stubborn Granada defense with a length-of-the-pitch long ball from Victor Lindelof to Marcus Rashford, whose finish gave United a 1-0 lead it would not relinquish. In the former, Real Madrid's eventual 3-1 two-legged quarterfinal win over Liverpool was set in motion by early deep shots, namely Toni Kroos' long pass to Vinicius Junior, which hit the young Brazilian in stride and, a few seconds later, gave them the lead.

In the first leg against Liverpool, Los Blancos attempted 18 "switches of play" -- as large a number as you'll ever see -- where a long pass is played laterally from one side of the pitch to the other, and completed 45 of 77 "long balls" (defined as passes that travel at least 35 yards in length). Their willingness and ability to stretch the field with accurate passing was both remarkably effective and not at all new -- in fact, their season completely turned around when they began to go deep a bit more.

Wait, is Real Madrid winning with "Route One" soccer?

Not exactly.

"Route One," refers to the old, English predilection toward verticality -- essentially long, aerial passes sent far and high down the field, usually soon after a change of possession, with the mostly fruitless intention of creating fast-break opportunities. Teams would deploy a "target man" to reel in the long passes and wait for reinforcements to arrive, and off they would go.

Plenty of lower-level English clubs still deploy that general approach; even in the second division, Rotherham United and Wycombe Wanderers both use extremely vertical tactics, albeit not very well, as it's looking like they could both drop to the third division in a few more weeks.

A couple of more successful and, perhaps, semi-modern "Route One" examples can be found in Spain. According to Stats Perform's Direct Speed measure, which looks at the average distance traveled for teams' possession sequences, the most vertical teams in Europe's "Big Five" leagues (English Premier League, Italian Serie A, German Bundesliga, Spanish Primera Division and French Ligue 1) are Cadiz (2.19 direct speed) and Osasuna (2.18).

Their possession rates are terribly low -- 34% and 42%, respectively -- and they both average under one goal per match, but quick, aspirational attacks with minimal players involved allow them to maintain their defensive structure. They can make life very annoying for possession-minded opponents, both because of their ability to play "park-the-bus" defense and take advantage of said teams' high defensive lines as they compress the pitch and push for goals.

In their first season in the top flight since 2006, Cadiz is in 12th place and safely out of the danger zone, having alternated between excellent results (seven points in three matches against Barcelona and Real Madrid) and blowout losses (4-0 to Celta Vigo and Athletic Bilbao, 3-0 to Sevilla, etc.).

Osasuna is one point behind in 14th. They limped through a miserable stretch of six points in 13 matches from November through January, but they've since pulled themselves to safety on the power of 1-0 wins, 2-1 wins and 0-0 draws. They scored one goal in a recent six-match span, but still pulled six points from those matches. Needless to say, they do not rank high in "watchability," but this approach will keep both teams in the top flight for 2021-22.

Barnsley could make the Premier League this year playing its own variation of Route One. If you're looking for a team deploying the Daryl Morey, "Launch-and-Squish" style, the Tykes might be it. Their direct speed (2.27) is the highest in the English Championship beyond Rotherham (2.34) and Wycombe (2.37), and their average of 124.5 possessions per game is by far the highest in the league.

Stats Perform records 24% of their passes as long balls (fourth-most), and 54% are forward passes (second). Their general goal is "get the ball the hell out of their end of the pitch as quickly as possible," and they combine that desire with extreme pressing tendencies when the ball is at the other end: they're allowing 10.8 passes per defensive action (third-fewest), and they're starting 9.2 possessions per game in the attacking third (most).

You can't say it isn't working. Barnsley has dropped only seven points in their last 14 matches and has moved from 11th place at the start of February to sixth, and a potential spot in the promotion playoff. They are combining raw, "Route One" tendencies with modern pressing techniques, and the addition of athletic American finisher Daryl Dike (eight goals in 14 matches) has pushed them to a new place, too.

Route One and its variations are, in today's game, classic underdog tactics. Real Madrid doesn't do "underdog tactics."

Zinedine Zidane's side maintains sturdy possession principles at all times -- their possession rate this season is 59% in both La Liga play and the Champions League -- but their technical prowess in the passing game, and a slightly more aggressive mindset, has opened up random quick hitters, too.

Real Madrid is one of two teams in Europe's "Big Five" leagues to both (a) average at least 1.75 points per game in league play and (b) average at least 0.3 long-ball completions per goal in sequences resulting in goals. They are averaging 0.32; only Inter (0.35) is higher. But of their 16 goals with long-ball sequences, 15 have come since they actually began playing well.

In early December, Real's season was on the precipice. After losing twice to Shakhtar Donetsk and barely eking out a draw against Borussia Mönchengladbach, they didn't qualify for the Champions League elimination rounds until their sixth and final group-stage match. And even after an unconvincing win over Sevilla on Dec. 5 -- their only goal was an own goal -- they were fourth in La Liga, having suffered demoralizing losses to both Cadiz and Deportivo Alaves and been thumped 4-1 by Valencia.

Their defensive structure was mostly fine, but their attack was stagnant. Karim Benzema was shouldering a heavy load and was leading the team in goals and assists, but with only four and three, respectively. Kroos had zero assists.

Maybe the idea sprouted from scouting Inter. Maybe it came out of desperation, or a moment of impromptu genius that turned into a steady tactic. But following a 2-0 win over Atletico Madrid -- another win featuring an own goal and no clear expected goals (xG) advantage -- Real's attack found some pep.

It also found the long ball.

- In a 3-1 win over Athletic Club on Dec. 15, they broke a scoreless tie by traversing the length and width of the field over a 30-second sequence, which started with a switch of play from Raphael Varane to Ferland Mendy and ended with Kroos knocking in an open shot from 25 yards. In second-half stoppage time, they put the win away with a counterattack triggered by a long Luka Modric-to-Benzema pass.

- On Dec. 20 against Eibar, a long pass from Casemiro toward Benzema in the center circle triggered a sequence that ended with another long pass, this one a lob from Rodrygo to Benzema in the Eibar box for a tap-in and go-ahead goal. After a turnover in stoppage time, a long reversal from Casemiro to Lucas Vazquez started another counterattack that put away another 3-1 win.

- On Dec. 23, Kroos became the main "long ball" guy. He lobbed a pass from midfield toward the sideline to Ferland Mendy, who connected with Marco Asensio, who crossed a ball in for a Casemiro header to put Real ahead of Granada. On Jan. 2, Kroos found Asensio via "Route One," and Asensio eventually crossed to a wide open Vazquez for the go-ahead tap-in.

And so on, and so forth. Long balls -- two from Kroos, one from Modric -- triggered three goals against Alaves, and then three long balls in a single sequence, one of the prettiest and most extended you'll ever see, led to a Kroos goal that put away Valencia on Valentine's Day. It's clear that it was a conscious decision to stretch the field, both vertically and horizontally, through the passing abilities of their aging, but still gifted, midfield.

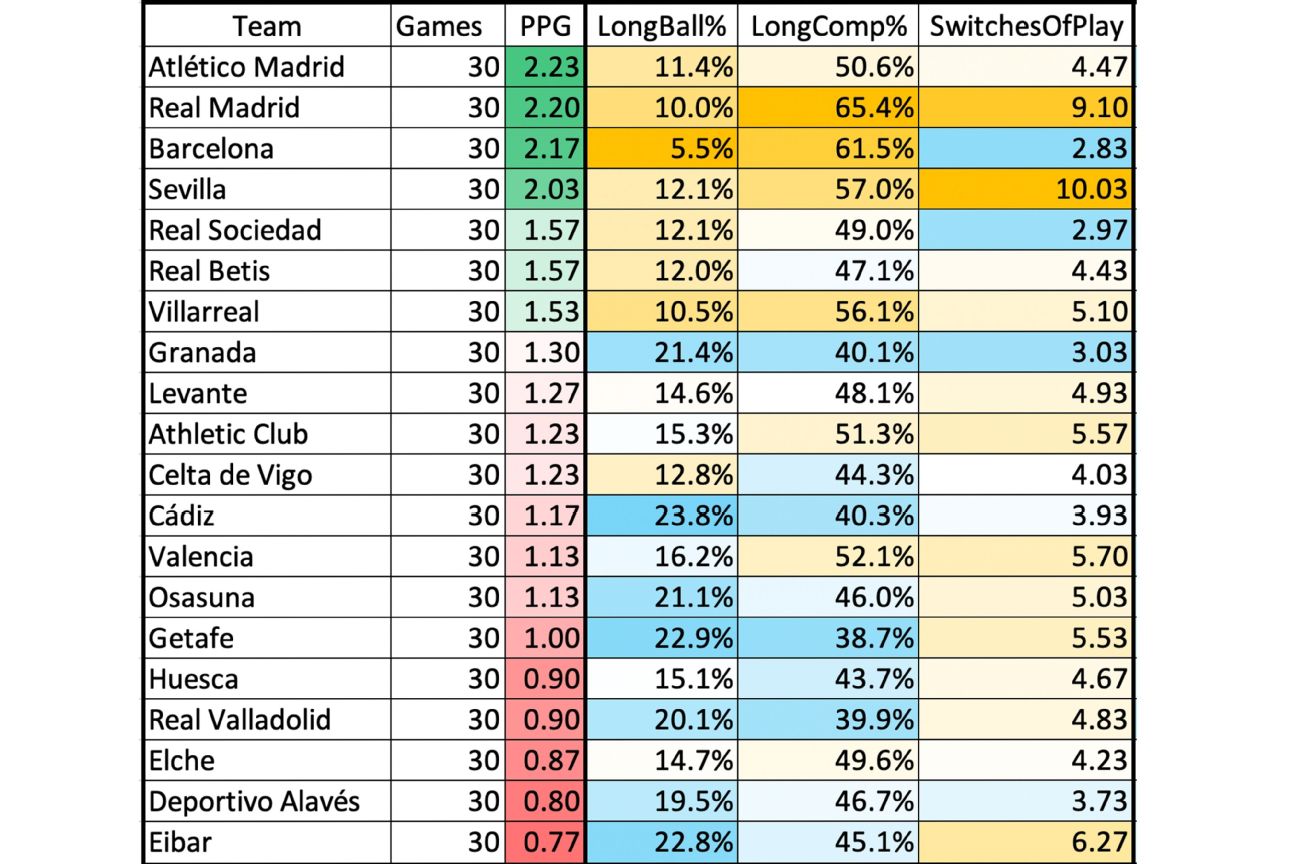

Through Dec. 14, Real Madrid was averaging 1.6 goals in 10.7 shots per match. They were attempting 55.6 long balls per match (9.7% of all passes) and completing 61.5% of them. Since, they're attempting 59.6 long balls (10.2%) and completing an incredible 67.8% of them -- about 20 percentage points higher than the league average. They're at 65% for the season, easily the best, and only Sevilla averages more switches of play.

Since Dec. 15, Kroos has completed 220 of 251 such passes (87.6%), and Modric 119 of 149 (79.9%). Kroos has completed long balls in six sequences that resulted in goals; in Europe's "Big Five" leagues, only Bayern Munich's Joshua Kimmich (7) has more, which is impressive considering Kroos' first didn't come until late-December.

They're completing 40-yard passes at the rate most would complete 20-yarders, and the team's output has increased to 14.8 shots and 1.9 goals. They've also gone from 1.9 points per game to 2.4. Following their 2-1 win over Barcelona this past weekend, they're just one point out of first place in La Liga. And thanks to Kroos' long passing, they indeed advanced past Liverpool and into the Champions League semifinals.

Zidane is generally regarded as more of a tweaker of tactics than any sort of revolutionary. "Have technically gifted passers look more vertically with their technically gifted passing range" is a tweak almost no other team in the world can follow, but it is perhaps his greatest tweak to date, and his Real Madrid could end up champions of both Spain and Europe because of it.

Who knew that the soccer equivalent of Patrick Mahomes would end up being a 31-year-old German midfielder?