|

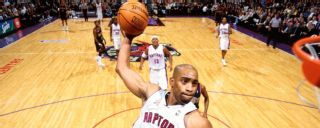

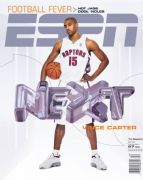

Editor's note: This story, which named Vince Carter as the NBA's next superstar, was originally published in the Oct. 10, 2000, issue of ESPN The Magazine. On Thursday, after 22 seasons, Carter announced his retirement from the NBA. VINCE CARTER ARRIVES in three-second bursts, or about as long as it takes for two dribbles and a dunk. This is what you know before you know anything else. This is the introduction. Two dribbles and a dunk doesn't tell you much. If they're the right three seconds, they can tell you that gravity is somebody else's problem. Those three seconds can help explain why Carter is seen on late-night television as often as a Chuck Norris infomercial. In the span of those three seconds, he can make you open your mouth involuntarily and shake your head and look around for someone to did-you-see-that with, even when you know you're alone. Watching him take someone off the dribble and dunk, as he did most famously to Indiana's Chris Mullin last season, is like watching a large animal devour a smaller one. But beyond those surface facts, beyond the immediate awe, you're on your own to take those three seconds and expand them into something deeper and more substantial. Two dribbles and a dunk definitely doesn't tell you about Carter's senior year in high school, when Charles Brinkerhoff, his coach at Mainland High in Daytona Beach, implored him to shoot the ball more, to take it to the basket, to make every game his own. Carter's friends say he could have averaged 40, easy. So put us on your back and carry us, Brinkerhoff told him, and we'll win the state championship. No, Carter said, for two reasons. First, he already had his scholarship. His path was set; he was going to North Carolina. He had been filling Florida gymnasiums and college coaches' imaginations since he was 14. What would a few more points per game mean to him? He had his, and he possessed the quiet assuredness to know there would be more for him in the future -- much more. But if he devoted his senior season to passing more and showcasing his teammates' abilities, maybe they would catch someone's eye and get the chance to play college ball. Second, Carter wanted to win the championship as much as his coach did, and he was perhaps the only one who believed he would increase his team's chances by increasing his assist total. So he listened to all those voices espousing selfishness and chose to ignore them. He still filled gyms, imaginations and highlight tapes, but his scoring average went down nearly four points a game from his junior to his senior year. In the end, two of Carter's teammates went on to play college basketball. And Mainland won the state championship. Even today, when asked how much of a stretch it would be for him to average 30 a game for the Raptors, Carter winces and says, "I don't know about that. To get to 30 ... that's a lot of shots." Two dribbles and a dunk? Think of it this way: Every movie needs a trailer.  Vince Carter is The Magazine's Next Athlete 2000 for reasons that go beyond his ability to provide the viewing public with three of the most captivating seconds in sports. He is Next because the only complaint you'll hear from his coach and teammates is that he doesn't shoot enough. He is Next because he listens to his mother and accepts criticism and defers to the wishes of his older teammates. On the court, two dribbles and a dunk is nothing more than an appetizer. Carter is the rare player whose presence fills unoccupied spots on the floor, in much the same way as his body seems to turn elastic in midair. He is simultaneously graceful and emphatic, and his exponentially improved perimeter game has made hope and prayer the most plausible defensive strategy. He is also Next because he absorbs the incessant comparisons to Michael Jordan while seeing them for what they are: flattering, burdensome and utterly unattainable. He has a combination of ability, humility and civility that once seemed to emanate from a different basketball age but is now -- if everyone would just look past the Sprewellian veneer -- making a comeback through people such as Carter and Tim Duncan. Carter, in fact, carries himself on the court like someone who knows -- with decimal-point precision -- exactly how good he is and yet does not view life as an endless opportunity to shove that knowledge down the world's throat. He is Next because he believes he can win championships and achieve fame -- even special, first-name-only fame -- while playing in Toronto. He's a 22-year-old from Florida who went to college in North Carolina, and yet he has not asked out of Canada. He has not complained about the cold or the accents or the currency. Instead, he says, "This is a perfect situation for me. We're on the way up." In fact, when he first got to Toronto after the '98 draft, he called his friend Joe Giddens back in Daytona and said, "Joe, this is awesome -- you need to come up here and check this place out." As if to reaffirm our wavering belief in karmic justice, Carter's contentment with Toronto is being repaid in both love and victories. Originally, fans and media in Toronto questioned the draft-day trade that made Carter a Raptor and sent North Carolina teammate Antawn Jamison to Golden State. Carter had been the second-best player on his college team, the argument went, and he'd never seemed to play up to his talent level. But now Carter's image is everywhere in Toronto -- storefronts, buildings, clothing -- and the nickname "Air Canada" is gaining wider renown. He is picking up admirers like lint. His name has been uttered in the same sentence as the letters NBA MVP. Premature? Probably, but after the Raptors beat the Lakers in Los Angeles in November, Shaquille O'Neal got all rap-like and called Carter "half a man, half amazing." Duncan and Spurs teammate David Robinson had to be thinking the same after Carter dunked over each of them on his way to 39 points soon after in a Raptors win over the defending champions. "We've been lucky -- really lucky," says Toronto general manager Glen Grunwald. "Vince has been a gem from the start. You have to remember, he came to us during a time when we were way down. Nobody wanted anything to do with us, and we needed someone like him. I guess you could say everybody does."  Carter's signature moment came in that win over the Lakers, when he scored 34 points and grabbed 13 rebounds. The team followed up with a victory over the Jazz, after which, on that same road trip, Carter did something even more amazing than the amazing Shaq: Against Golden State, with his team leading by 33 points midway through the third quarter, Carter took a charge. The game had long since achieved epic irrelevance when Warrior forward Tony Farmer -- 6-foot-9 and 245 pounds, 30 more than Carter -- took a wild and angry drive through the lane. Carter stood mannequin-still and took Farmer's knees full throttle in the chest. Toronto coach Butch Carter watched with what had to be a mixture of pride and outright dread. Butch says Vince's best attributes -- not that any non-coach would bother to notice -- are his effort and intensity on defense. He led NBA small forwards in blocked shots last year, and his coach says he should do it every year. Praising Vince's defense seems a little like saying Bill Gates has a nice library, but you get the idea. Carter's signature moment came in that win over the Lakers, when he scored 34 points and grabbed 13 rebounds. The team followed up with a victory over the Jazz, after which, on that same road trip, Carter did something even more amazing than the amazing Shaq: Against Golden State, with his team leading by 33 points midway through the third quarter, Carter took a charge. The game had long since achieved epic irrelevance when Warrior forward Tony Farmer -- 6-foot-9 and 245 pounds, 30 more than Carter -- took a wild and angry drive through the lane. Carter stood mannequin-still and took Farmer's knees full throttle in the chest. Toronto coach Butch Carter watched with what had to be a mixture of pride and outright dread. Butch says Vince's best attributes -- not that any non-coach would bother to notice -- are his effort and intensity on defense. He led NBA small forwards in blocked shots last year, and his coach says he should do it every year. Praising Vince's defense seems a little like saying Bill Gates has a nice library, but you get the idea.

When Carter is on the floor, he wears a look that says his mind is working a play or two ahead. Even when he does something spectacular, and even when he lets his feelings show with a low-Richter celebratory shoulder shrug, his face does not appear to be partaking in either the revelry or the exertion. He is calm on the court and calm off it, sitting back in the Raptors' locker room with his wire-rimmed glasses giving him a stately look, telling a reporter he honestly doesn't know how he does some of the stuff he does. Often he leaves the ground and makes it up in midair. (Ah, the joys of hang time.) By the sound of it, he can be rendered as slack-jawed as anybody else by those three-second film clips. The surprise is often his, as well as ours. He is accustomed to the attention his talent brings, and expert at deflecting it. He is charmingly noncommittal and noncontroversial, liberally sprinkling his conversation with compliments for his teammates. "Just taking the shots that were there," he said after the Laker torching. Twenty-two years old or not, Vince Carter has lived most of his life in the glare of the hard lights. In high school, the sellouts started at the beginning of his sophomore season. By his junior year, scalpers were working the parking lots two hours before game time. He always felt the tug of the crowd and tried to live up to the expectations. "He was always a ham on the court," says longtime friend Cori Brown. "Then after the game, he would change back to being a quiet, humble guy. He was raised to have morals. He was raised not to act better than anyone else." Friends from Florida still call when they have trouble at home or at school. "Whenever I need advice, I call Vince," Giddens says. "He's the best listener I know." Vince's mother is a schoolteacher and his stepfather (whom he calls and considers his father) was the band director at Mainland. Vince was a drum major and played sax, and he was good enough to be offered a music scholarship to Bethune-Cookman. When he decided to attend North Carolina, his mother got him to sign a contract decreeing that, if he left school early for the NBA, he would still finish his college education. The day he announced his intention to leave after his junior year, Michelle Robinson-Carter pulled the contract from a drawer and showed it to her son. And in the summer of 2000, assuming he completes his one remaining class, Vince will earn his bachelor's degree from North Carolina, in African-American studies.

More from Tim Keown Sammy Sosa, Mark McGwire and what we should have known A year after Anthony Joshua upset, what happened to Andy Ruiz Jr.? Ferraris, nail salons and armed guards: Two weeks with Dennis Rodman in the mid-1990s

BASKETBALL IS WHERE sport and culture mix, where kids from crumbling downtown blacktop and kids with full courts in their backyards come up with the same ideas on behavior and fashion and celebration. Basketball is the only sport in which shoes are advertised with release dates, as if they were movies or criminals. With Carter, you can see it coming: His talents -- especially his felonious leaping ability -- are putting him at the forefront of the current generation of players. Throughout the league, he has gone from being a sidelight to being a major attraction. The NBA -- ever image-conscious -- has informed him that it is interested in promoting him nationally. Watching Vince now is to bear witness to the incipient moments of uber-stardom. This, his second season in the NBA, is the cultural equivalent of the little nod he gives Muggsy Bogues or Dee Brown before they deliver a lob pass that will inspire his 41-inch vertical-leaping legs into the air for a dunk that will have opposing fans high-fiving in the aisles. Carter's on-court maturity is typified by that game in L.A. He had the crowd reacting as it always does when it sees something that defies logic, but the highlights served a greater end: The Raptors got the win. He took the game over, lifting his team a solid level higher in an NBA universe that beats to the pulse of instant respect. Carter is gradually, sometimes grudgingly, becoming confident enough to grab a game by its collar and smack it silly for 48 minutes. At this point, where expectations become demands, it gets difficult for Carter. There is still a little voice in his head (Dean Smith's, perhaps?) that cautions against shooting too much, and cautions against showboating, and cautions against anything that might detract from the sanctity of the team concept. The problem is obvious. Carter's is the kind of talent that demands a certain arrogance. Selfishness is the average player who takes 15 shots in a loss to pad his stats. But when a player like Carter takes 20 shots in a close win, the operative term is leadership. He is just beginning to understand the distinction; he generally starts games slowly and gradually works his way in from the margins. Butch Carter rolls his eyes in exaggerated frustration -- as if he were Method-acting the role of exasperated father -- when discussing his attempts to get Vince to claim ownership of a game, Iverson-like, from the opening tip. "I'm scared my mentality is going to change," Vince says. "I'm afraid I'm going to start thinking, 'OK, it's the third quarter, how many points I got?' I still can't get used to looking at the stats and seeing that I took 23 shots." What he's saying without actually saying it is this: It's there when I need it, so why force the issue? The Raptors have mixed Carter and distant cousin-by-marriage Tracy McGrady, 20, with hard-boiled veterans Charles Oakley, Antonio Davis, Kevin Willis, Brown and Dell Curry. The roster radiates perspective, and its constituents are not bashful about voicing their opinions. Davis chastised Carter and McGrady for a perceived excess of showmanship during the preseason. "It needed to be said then," Davis says, "but it hasn't been needed since." Butch Carter, wearing an "Old School" sweatshirt during a November practice, said Vince and Tracy sometimes allow their emotions, their friendship and their talent to take them in unproductive directions. Do they get carried away sometimes? he is asked. He nods his head and rolls his eyes, the father again. But what the coach also knows is who does the carrying for the Raptors: Vince averaged 18.3 points a game last year and won Rookie of the Year as Toronto made an unexpected, ultimately unsuccessful run at the playoffs. He got better and more confident as the shortened season wore on, his scoring average increasing each month. This year he is averaging more than 22 points a game and, at 6.4 per game, is one of the best rebounding small forwards in the league. "Once he realizes how good he is, then look out," Davis says. "He's learning, but he still doesn't have a good idea of what's out there for him. One thing about this room: We'll let him know what we think. One thing about Vince: He'll take it the right way."  THE FIRST TIME Vince Carter knew he was entering a big, big world came in October of his freshman year at UNC. He and his high school friend Cori Brown, who served as the Tar Heels' team manager and Carter's roommate, were watching television. They flipped to MTV and stopped at an episode of "Dance Party." There were people on some far-off beach wriggling and gyrating for the benefit of the roving cameras, and two of them were wearing No. 15 Carolina blue Tar Heels jerseys. His jersey! He was a freshman in college, 18 years old, and before he had even played a game, he was sitting in his dorm room watching as a part of himself was delivered and aired to the greater world. They were stunned. They knew the university was selling the jersey, and they figured they knew the reason: Jerry Stackhouse and Rasheed Wallace had left for the NBA, and the enormous expectations placed on Carter made him the most likely -- and most marketable -- personification of the Tar Heel program. Even so, seeing the jerseys on television was totally different from seeing one on a classmate in the cafeteria. Brown kept saying, "There's your jersey on the TV," and Carter sat there silent, a frozen grin spread across his face. There don't appear to be many rules to "Dance Party," one of the world's foremost showcases of exhibitionism and narcissism, but it's clear that cool is currency. You don't show up wearing a Matt Bullard jersey or a Clippers warm-up jacket. For a grown person -- even a grown person with a desire to appear on "Dance Party" -- to spend money on a Vince Carter jersey at that specific moment in time was equivalent to a broker buying a stock on spec. In this case, the future earnings were cultural rather than financial. That random channel surf said a lot to Carter, though it would take him a while to understand it all: the weight of expectations and the reality of responsibility; the power of talent as it commingles with hope and commerce; and the reality that, should he fulfill the promise of that jersey, no decision from then on would be entirely his. The Raptors' media relations office says it fields at least 10 interview requests a day for Carter. It is his mother's wish, conveyed through his personal publicist, that Vince never be interviewed alone. You can call it overprotective, or you can call it the sound parenting of a young son who is being borne rapidly along the superhighway of fame and opportunity. A year ago, the Canadian company in charge of importing genuine NBA merchandise had to call for an airlift of more Vince Carter jerseys into the country from Mexico just to keep up with demand. In other words, it's a big world out there, and if Vince can make Canada NBA-crazy ... well, you just never know. "Going to North Carolina, you learn that everything you say and everything you do is out there for everyone to see," Carter says. "You learn how to handle yourself and what to say. It's something I'm comfortable with, because I'm used to it." This, of course, brings up the fact that Vince Carter despises comparisons. More to the point, he despises The Comparison. He's 6-foot-6, went to Carolina, left after his junior year, has a telegenic smile and thrills the world in three-second bursts. To anyone who feeds at the big trough of sports hype, the temptation is simply too strong. When his publicist inquires about the focus of this article, she inquires politely, "I have to ask: Is this a comparison between him and Michael Jordan? Vince really hates that." Carter has no problem with Jordan at all; he knows him, reveres him, even worked one of his camps. But what no one can understand -- and what Carter can't say -- is that The Comparison diminishes everything he's done. It reduces the hours of weight work, the endless shooting drills, the cardiovascular routines that consistently make him the first one down at both ends of the court. The Comparison makes it sound as if he was manufactured or created. It's flattering and demeaning at the same time; it removes the sweat and blood and self-doubt from the equation, leaving an easy, ready-made conclusion. In all fairness, it also must be said that modesty is not the sole reason Carter recoils from the Jordan linkage. He knows The Comparison is unfair not only to him but to anybody who receives it. He knows it is meant as a compliment but absorbed as a burden. He knows any comparison with Jordan seems destined to end as a parable of unfulfilled promise. He also knows there isn't much he can do about it. Still, there's something unspoken here, too, something he won't say but others will. "He doesn't want to be the next anybody," says his friend Giddens. "His goal is the same as always: He wants to be the first Vince."

|