| ||||||||||||

| ESPN.com NFL | ||||

| Friday, February 11 One teacher produced two hometown All-Stars Special to ESPN.com | |||

They probably would have been friends anyway. But fate being what it is, Gary Payton and Jason Kidd began their relationship a long time ago.

You would think, if you had to venture a guess, that they would possess the game of the other. Kidd, the quiet, unassuming guy from The Hills of Oakland, with the flashy game that does not seem to fit his withdrawn personality. And Payton, the brash, foul-mouthed trash-talker from The Flats, who displays only the sound fundamentals of the game. That their play is the antonym of their person only adds to the intrigue.

Five years separates them in age, money separated them in Oakland, but these days, at the zeniths of their careers, as they prepare to head home as the sort of unofficial hosts of the NBA's All-Star game, not a lot separates them on the basketball court.

| |

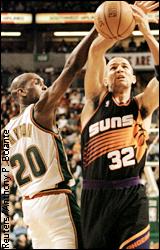

| Payton and Kidd return home to Oakland for this weekend's All-Star game. |

Kidd, 26, actually met Payton, 31, while Kidd still was in elementary school, being coached on his youth teams by Payton's father.

He's the guy in the commercial, the one of the license plate that reads "Mr. Mean," the man whom Payton said beat out even George Karl in terms of craziness.

"His Dad was impressive, that's for sure," Kidd said with a smile. "He didn't take any stuff. He wanted the best for you, and he definitely worked you."

That's the abbreviated version, the kind version, Kidd trying to be politic about somebody's else's Daddy. Payton is not so diplomatic. Of course, he had to live with the man.

"He screams on you," Payton said. "With Jason, he did the same thing. He knew Jason was a better talent, and even if Jason did something good he would scream on him. He did me the same way. He would pick on us because he would want us to get better. We would think that our game is better than everybody else and get satisfied that we did something, but we wasn't improving the team. He would always stay on us, and he was crazy.

"He would grab us by our collar and sit us down and tell us, 'We don't care; we don't care who you are. You'll sit here all day if you have to.' Jason learned from that and that is where he got his toughness from in going against a lot of people."

Payton, of course, can see the value of the upbringing now, with the objectivity of distance and maturity. Back then, he said, he was angry.

"It was hard, because I didn't understand why my father always picked on me," Payton said. "When you thought about it, you would say, 'Well that's my father, why would he want to do that? I'm scoring these points, I'm doing these things to win these games, why is he always picking on me?' And then now that we think about it, he did it for our own good because he made us a better player."

He made Payton, at least, a better person, too. Once, when Payton was in school, his father heard the news that Payton was goofing off in class. His father's approach was a bit unorthodox, but it certainly proved effective.

"He snatched me out of the room and told the teacher that he had to talk to me for a minute," Payton recalled. "I went back in there crying in front of all my friends, and they knew what happened.

"It's always going to have an effect when your father comes up and scolds you in front of a lot of people. When you go in there, you don't want him to come back and do the same thing. I didn't want guys teasing me after practice or after school, 'His Daddy came in and got him again.' So I just left it alone."

As hard as Payton's father was on Kidd, he was even more stern with Payton. That, Payton explains, is the reason that his game is so understated. He never dunks, he never throws spectacular passes, he doesn't have an ankle-breaking crossover.

Kidd has all that. His game has become less animated as he has learned that efficiency is more productive than flash. Just ask Jason Williams. But go back to Kidd's early years in the league, right out of college, when he was trying to wow people, and there are passes that make the playgrounders in Harlem yearn for a How-to guide.

"That stuff is Jason, he is a flashier player," Payton said. "That wasn't me. That just wasn't my game. My father wouldn't let me do that anyway. If we would throw the ball away in a game, my father would take it out in practice. He said, 'Since Gary threw a behind-the-back pass and this and that on the fast break, then everybody got to run.' It was one of them things where I didn't want all those guys to be mad at me all the time if I did something wrong."

Because they grew up in different sections of Oakland, and because Payton was older, the two never actually met on the basketball court in their formative years. But Kidd said he knew all about Payton, the second in a long lineage -- behind Brian Shaw -- of players from Oakland now scattered around the league.

Back then, St. John's was a major power in college basketball, and Payton was supposed to attend the school in New York. He would have been teammates with Mark Jackson.

| “ | You want to go against the best, and Gary was the best. He still is the best. It's something every professional athlete thinks about, is going against the best. To me, it was a dream come true to play against Gary or with Gary. You are going to get the best out of him every time he steps out on the court. ” | |

| — Jason Kidd |

"He was a legend in Oakland," Kidd said. "Everything that happened with him, and not going to St. John's, that got a lot of attention too. Then he chose Oregon State. That was not big time or well known, and he helped put that school on the map."

It was around that time that Kidd and Payton played for the first time. Payton was about 20 and Kidd was 15. They played at the University of California's Harmon Gymnasium. Kidd could barely get off his shot, much less dominate the way he was accustomed.

"That was when he was young," Payton recalls. "I taught him how to play defense, how you do it."

That's a nice way of saying Payton put the clamps on him. But Payton said Kidd did not take it personally, and their workouts became a regular thing.

"When you are a young guy like that, a guy who has been dominating his peers, he starts thinking, 'Well, I got to get better.' And that's what he did. He said if he thought he could score against me, I could score against anybody. And he just got better. He wouldn't take it in a negative way, he would just come back the next day and work harder with me."

Now, Kidd says, "You want to go against the best, and Gary was the best. He still is the best. It's something every professional athlete thinks about, is going against the best. To me, it was a dream come true to play against Gary or with Gary. You are going to get the best out of him every time he steps out on the court."

In a way, although some would say that Kidd is a better player, Payton still is the tutor and Kidd still is the protege.

Last weekend, the Sonics and the Suns met for a home-and-home series over the span of three days. On a Friday night, Payton had 23 points, a career-high 13 rebounds and seven assists. Kidd had 12 rebounds, six assists and only eight points after missing 11 of 14 shots. Payton's team won, 94-86, after which Payton pulled aside Kidd and told him he was not shooting enough.

"Gary has always given me advice, and I have always listened and taken it to heart," Kidd said. "He will give advice and you always have to listen because he understands and that's how he got where he is at.

"I think offensively, he has told me to look to score, look to take the shots when they come to you. That is always been something that he has griped at me about is that I look to pass too much, and he tells me that you have to show them that you can score."

After Payton issued his advice, Sunday Kidd went out and got 22 points, 12 assists and seven rebounds while Payton had just 13 points on 4-for-18 shooting, seven assists and seven rebounds. Kidd's team won, 105-93.

"When I see something is wrong with him, and he is not scoring and doing things, I tell him," Payton said. "If you don't shoot the ball, you don't know if it is going to go in. I take it (giving him advice) as what I am supposed to do. I'm not a jealous guy. I want Jason to succeed as much as anybody. I want him to learn and understand everything that I've been taught. I didn't have a guy like me in the NBA or going into college that could teach me to play basketball that way. Everybody was always my same age and Jason got a big advantage from that. I take it as a thing I should do."

The irony, of course, is that while Payton has passed on his knowledge, Kidd is widely considered the better player. Kidd was voted into Sunday's lineup as the starter, while Payton, the mentor, is a reserve.

"That's some people's opinion," Kidd says, almost disputing the notion. "Some people say he is the best. I'm sure there is a fine, cut line of who is the best."

Payton said he doesn't care, and even in the NBA world where lip service is a common practice, he truly doesn't. He would have used to, he admits, when he was young, dumb, trying to prove himself, make a name, gain bragging rights.

But he is 31 now, and accolades don't mean the same thing they used to. He understands that the NBA is the world of commercialization, and whomever has the most 7-Up spots on television or Nike endorsements is more than likely going to be named the All-Star starters.

"We're just going to have fun," said Payton, who will gather at his mother's house Thursday with friends and family for a fried chicken banquet before the weekend gets started.

For Kidd, this is not like that scene in "The Great Santini," where Robert Duvall's son finally beats him in the family driveway and storms off in triumph, leaving his father to rectify his own mortality.

Kidd seems almost apologetic that he got the votes instead of Payton, as if he has unwittingly stolen something from the player who already gave him so much, deserving as he may be.

Then again, this is the All-Star game, not Harmon Gymnasium. The whole world will be watching, and while Kidd knows and remembers his roots, he also is realizing something that he has envisioned since those days when Payton's father nearly broke his eardrums with vitriol.

Even better, at some point on Sunday, probably midway through the first quarter, Phil Jackson is going to motion to Payton, sitting over on the bench, to come into the game. He will join Kidd on the floor, and half the arena will see products of Oakland, their own, making up the Western Conference backcourt.

The only question that remains is who is going to shoot?

|

ESPN INSIDER

Copyright 1995-2000 ESPN/Starwave Partners d/b/a ESPN Internet Ventures. All rights reserved. Do not duplicate or redistribute in any form. ESPN.com Privacy Policy. Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Service. | ||||

Fouled Out: Mailman not fooling anyone

Fouled Out: Mailman not fooling anyone