|

|

| | Tuesday, September 7 | ||||||

Associated Press | |||||||

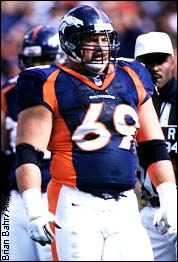

| He keeps orthopedists busy around the clock. He goes for surgery about as often as some people go to the store for socks. An entire health-maintenance organization could be built around his aching bones.

For Mark Schlereth, a left guard for the Super Bowl champion Denver Broncos, the pain never goes away. "For seven seconds, during each play, I'm able to forget about it and put it on the back burner," he says. "As soon as the play ends, I start limping back to the huddle in pain." And he's not alone. In the NFL, just about every player is hurting. At practice, during games, after games. And the injuries don't have to be as agonizing as shredded ligaments or ripped hamstrings. The body just plain hurts. Everywhere. Take Schlereth. He's 33 and has had 25 operations, with his knees taking the brunt of it. He has had his gall bladder removed and back surgery for herniated discs. He has had a neurological condition that left him falling over himself. He once played a Monday night game hours after passing a kidney stone. "I said when I started it would be 20 surgeries or 10 years," he says. "Now it's 25 surgeries and 11 years, and I'm still going." Schlereth, the league's poster boy for mangled limbs and joints, has a medical history like no other. And his NFL colleagues might be the only ones who fully understand his grinding ordeal. This, after all, is a sport in which sculpted, 300-pound bodies encased in high-tech armor crash into each other at blinding speeds. And while a graphic injury -- Darryl Stingley's paralysis, Joe Theismann's grotesquely broken leg -- surely underscores the perils of the game, the daily routine of hitting and healing often is taken for granted. For fans bundled in parkas in a stadium's upper deck or plunked in front of a TV and fortified with chips, cola and beer, the unrelenting demands of pro football can be lost. "It's unexplainable," Miami Dolphins running back Bernie Parmalee says. "If you don't actually feel it, it's something you can't explain. It's tough. That's part of the business the fans don't see.

"It looks like it's not much. They don't see all the bumps and bruises you've got to fight through." Chicago Bears linebacker Rico McDonald had reconstructive knee surgery in 1993. He can't expect fans to comprehend the combat on the field. "I'll look at a basketball game and think, 'That looks easy,' " he says. "Then I'll go out to my backyard and shoot some hoops. It's not their fault. If you've never done it, there's no real way you can feel it. It takes a person who's done this to truly understand." New Orleans coach Mike Ditka, once the snarling symbol of football grit, points to bigger and faster players today and explains the laws of the game as a matter of basic physics. "I guess it's mass and velocity," he says. "When you get something moving at a certain speed, something has got to give -- the thing you're hitting or yourself. And that's basically what football's all about." The fan watching at home might be removed from the violence on the field, but the physical dimension of the game is still more palpable than ever on television. Ed Goren, executive producer at Fox Sports, says the enhanced use of sideline mikes the last five years provides a more natural sound replay, allowing viewers to "hear the hit." "Anybody who hasn't been on the sideline can't get a sense of the force of the hit or the size of the players," he says. The NFL Players Association does not catalogue injuries accumulated during a season. But consider a typical injury report from 1998: Week eight -- smack in the middle of the season -- with 12 games scheduled. The list reads like an account from a train wreck, with body parts scattered everywhere. In all, 140 players are cited for 27 ailments. The leading injury was to the knee (33 players), followed by the ankle (21) and shoulder and groin (10 each). "Everybody is dinged somewhere," Dolphins offensive guard Mark Dixon says. "You find a way to deal with it. The level this game is played at, you have injuries. There's no way around it." Bears trainer Tim Bream thinks a high threshold of pain is expected from football players because this is "such a Spartan sport." "Every sport is punishing in some way just because of the demands on the different body parts," he says. "I think from talking to different athletic trainers and different physicians that ice hockey is pretty similar because of the amount of games they have and the contact." Bubba Tyer has seen a lot of blood in his 23 years as trainer of the Redskins. He remembers when star offensive lineman Russ Grim, now an assistant coach with Washington, nearly lost his eye after being poked and was rushed to the hospital. He returned to the stadium with stitches in his eyelid. "He was mad at the ambulance driver for taking her time because he wanted to get back in the game," Tyer says. For many players, the best way to deal with the physical hardship is simple -- forget it:

But sometimes the pain is unmistakable, and the course of action indisputable: It's quittin' time. Green Bay wide receiver Robert Brooks retired during training camp. His knees, back and hamstrings were a mess, and he worried about all the medication. "I'm 29 years old," he said. "And after practice, I feel like I'm 50." Cleveland linebacker Chris Spielman quit two weeks before the season opener after a blindside hit left him numb. He had already missed a season and was coming off surgery to fuse neck vertebrae. "We're all football warriors," he said. "And being that, you have to accept your mortality." Still, few would trade what they have. Others outside football endure just as much pain, but without the celebrity, support and compensation. "It's the greatest job in the world," Dixon says. "You're getting paid good money and it's something you always wanted to do, so you don't even think about tomorrow." All the punishment might exact a price down the road. But Ditka, for one, doesn't regret it for a moment. For him, the pain is merely an occupational hazard.

"Sure it takes a toll on the body," he says. "So does sky diving. If the parachute doesn't open you're in trouble." | ALSO SEE Call it a comeback

Murphy: How the cookie crumbles

Malone: Ten things to watch in '99

| ||||||

Mort Report: Fearless forecast

Mort Report: Fearless forecast