| ||||||||||||

| ALSO SEE Tuesday Morning Quarterback

TJ's Take: Titanic development

| ||||

| SPORTS NBA | ||||

Thursday, September 30

Give us parity; it's boring us to death

Special to ESPN.com

You know who says "parity" the best? Ron Wolf, the general manager and chief architect of the Green Bay Packers. Wolf spits it out as part of a whole descriptive sentence, like this: "That six-letter word, parity." The way the word hisses off of Wolf's tongue, it sounds like a true pejorative -- sounds like it ought to have four letters.

And three weeks into the NFL season, with just about all of the 31 teams looking like a bet to finish somewhere between 7-9 and 9-7, that word is looking worse in action than Wolf makes it sound in theory. When you have accomplished that, you know you've got something.

| |

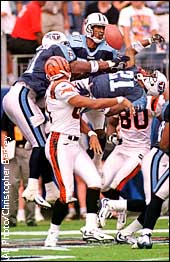

| Everything has been up for grabs in the NFL this season. |

Problem is, you don't want it.

If this is parity in the NFL, then, bartender, cut these people off immediately. No one is allowed another drink until we locate the responsible parties behind this charade and force them into a screening room to watch "Full House" reruns until all ears are bleeding appropriately. Then, we'll begin the penalty phase.

We understand the concept of parity; it's the actuality that emits all the gas. In concept, a hard salary cap acts as an artificial governor and allows smaller-market teams, like Jacksonville --and Wolf's own Green Bay, now that you mention it -- to compete on precisely the same terms as a New York or a Los Angeles. (Whoops: Make that New York and Wherever.)

It's a noble strategy that suffers from only a few dozen fatal flaws. First, it has unintentionally transferred a huge percentage of media attention away from the field and into the front office, which almost always is a bad thing. Does anybody ever sit up in his chair and say, "Think I'll go watch Pat Bowlen own the Broncos"?

Second, the full-force cap came along in the NFL at almost exactly the same time as a period of expansion. Expansion wickedly diluted the talent base, and the salary cap further denied teams the means to stockpile what talent they did come up with.

Result: One injury and you're out. The Jets and Falcons went from Super Bowl contenders to bunches of guys who cannot win an NFL game in the wake of single injuries. Granted, the hits came at positions of tremendous vulnerability leaguewide; but that's just the point: Does the league seriously want to see potential marquee teams reduced to rubble because its system isn't malleable enough to allow for emergencies?

A team that plays near us once had Joe Montana at quarterback and Steve Young on the bench. For four years. But times changed. When Young took over after Montana was traded to Kansas City, he had Steve Bono backing him up, but Bono became unaffordable at the No. 2 spot under the cap and eventually went to K.C. as well. Then, Elvis Grbac sat behind Young, until he, too, priced himself out of the market and into a big-money starting job in Kansas City, leaving the 49ers searching for a simple decent-quality reserve.

All of which leads to the reasonable conclusion that Kansas City ought to find its own damned quarterbacks. But the larger point is that NFL teams -- on appearance, at least -- have grown thinner and more shallow than ever, and while the Any Given Sunday results of that trusim are clearly in play, it's hard to argue that the league is better off for the trade.

We've said it before: The dynastic model in sports is, by and large, a solid model. It provides focus, clarity and easily defined rooting interest, for and against. The Packers' Wolf said recently that, were it not for the salary cap, the Dallas Cowboys of the early 1990s might have won four or five Super Bowls -- and what would have been wrong with that? Anyone have a problem with the Steel Curtain of the '70s or the Packers of the '60s or the 49ers of the '80s or the Bulls of the '90s or the Yankees of three or four decades?

Not at all. In fact, we'd suggest that some of the enduring sports memories -- and most of the greatest upsets -- of the century are tied into dynastic team performances.

Of course, it's repugnant to argue in favor of the richest teams constantly winning everything. The good news there is, rich teams over the years have bungled at least as many winning opportunities as their poor cousins. And is it really a better feeling to know that the Tennessee Titans are in great early-season position?

Scouting around

Mark Kreidler is a columnist for the Sacramento Bee, which has a web site at http://www.sacbee.com/.

|

ESPN INSIDER |

COMMUNITY |

BACKSTAGE

Copyright 1995-99 ESPN/Starwave Partners d/b/a ESPN Internet Ventures. All rights reserved. Do not duplicate or redistribute in any form. ESPN.com Privacy Policy (Updated 12/21/98). Use of this site signifies your agreement to the Terms of Service (Updated 01/12/98). | ||||

Murphy: It's all relative in '99

Murphy: It's all relative in '99