Editor's note: Just 10 of the top 30 of ESPN FC's #MLSRank list are eligible to play for the U.S. national team. This article originally published in April, but with so few U.S. internationals featuring in the U.S. and Canada's first division, the question was again raised about opportunities in Major League Soccer for U.S.-born players.

In the opening weeks of Major League Soccer's 2017 season, ESPN analyst Taylor Twellman alerted the viewing audience to a concerning set of numbers: 51.2 percent, 47.3 percent, 45.5 percent and 42.1 percent. Those figures, courtesy of Elias Sports Bureau, represent the percentage of opening-day starters who were born in the United States from 2014 to 2017.

Raw numbers tell a similar story. In 2014, 107 U.S.-born players started for Major League Soccer teams. In 2017, that number fell to 102, despite the total number of starting spots increasing by 33 through the addition of four expansion franchises and the closing of Chivas USA.

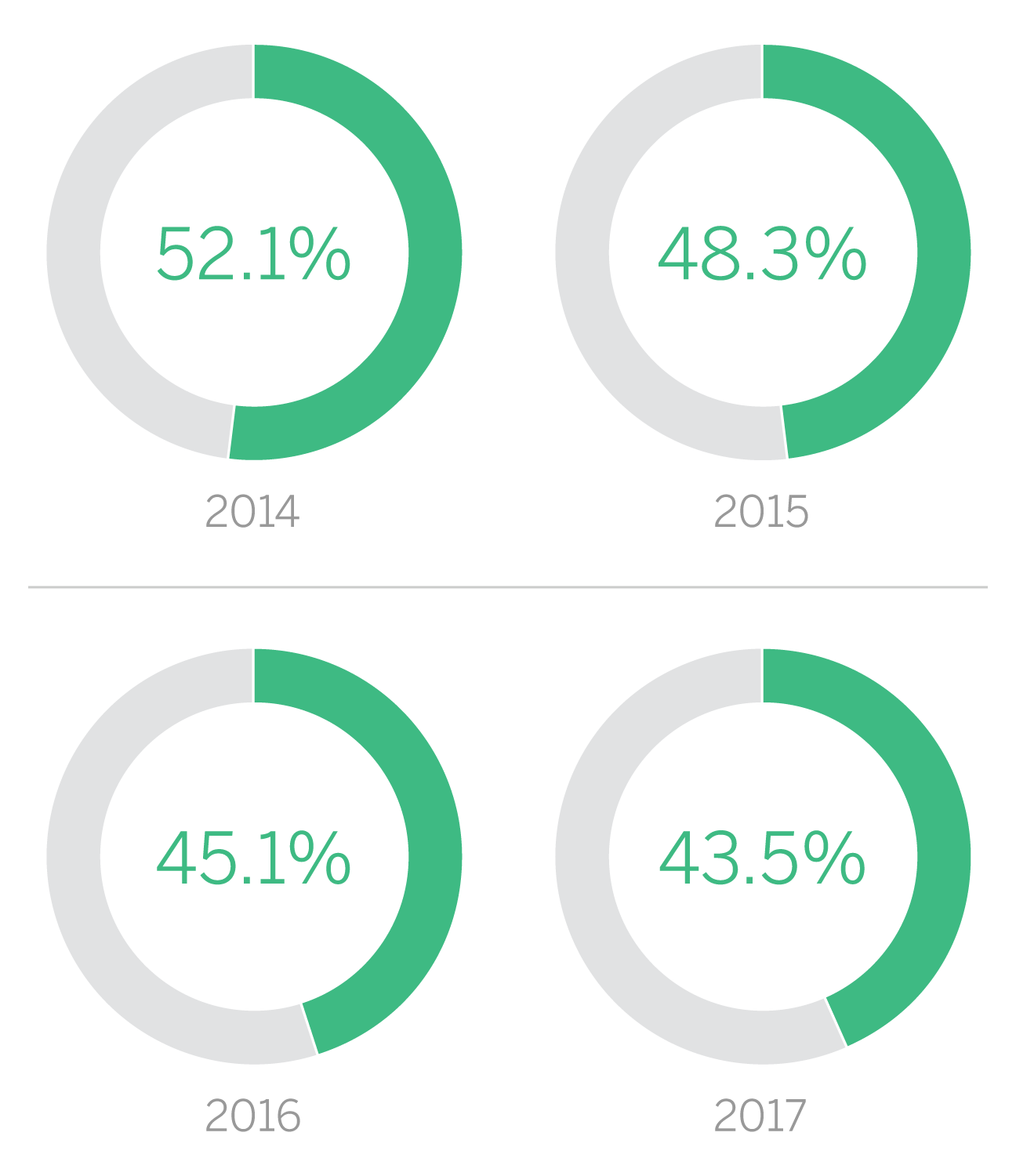

Seeking further detail, I asked Elias for figures about the number of U.S.-born players who played at least a single minute during a given season. The decline was about the same. In 2014, 260 of the 499 players (52.1 percent) were born in the U.S. In 2015: 253 out of 524 (48.3 percent). A year later, 230 out of 510 (45.1 percent). Through last week, the number was even lower for 2017: 181 out of 416, or just 43.5 percent.

Percentage of MLS players born in the U.S.

What does that tell us, and is it an issue?

"As a product of expansion, the importance of the American player is being pushed aside," Twellman said. "I don't think that's a bad thing right now. You have to keep the linear growth of the league and where it's going at the same level. Expansion is hurting the American player presently, but I don't think that's a harm. I think it's a harm if you and I are having this discussion after 2020 or 2022."

That sounds about right. MLS's first priority is not to improve the individual American player or even the overall level of soccer in this country. Rather, it's to improve as a league, to increase the level of talent on its teams. The fact is that right now, the U.S. has neither the depth nor the breadth of soccer-playing ability to keep up with MLS's rapid expansion and growing talent on the field. It's natural that technical directors, general managers and coaches look abroad, especially as their scouting networks develop and the domestic league's reputation gets better as a place where players want to play.

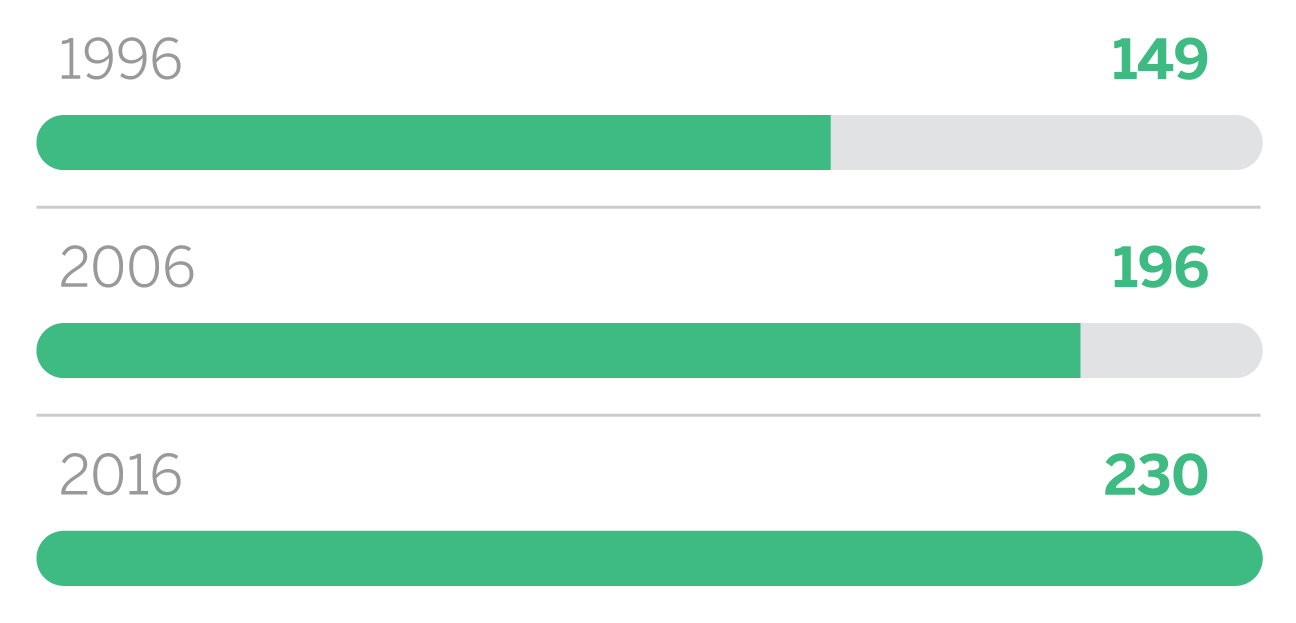

And MLS is producing more opportunity for Americans to play. The 230 U.S.-born players who tallied at least a minute of MLS action in 2016 is 81 more than 1996, 56 more than 2001 and 34 more than 2006. Could that number be higher, especially considering the percentage of MLS players born in the U.S. has dropped from 62.3 percent in 1996 to 45.1 percent last season? Of course. But more than 200 Americans will play professional soccer in the U.S. this season, which is absolutely a net-positive for the sport here.

MLS walks a line between growing as a league and growing the sport in this country. "Finding that balance is what we are constantly reviewing," said Todd Durbin, MLS's executive vice president of competition and player relations.

Because ultimately, the best thing for both MLS and the U.S. national team is a league teeming with American talent, but only because it's good enough to thrive. We are not there as a soccer-playing nation. How much priority MLS should put on making that happen remains an open question. But there's only so much money to go around.

"I don't think [developing American players] should be a primary focus, but I sure as hell hope it's in the top-three agenda discussions when it comes to on-the-field product," Twellman said. "If the national team does not qualify for the World Cup but Costa Rica, Honduras, Jamaica, all the other CONCACAF teams that have benefited from the growth of Major League Soccer do, someone explain to me how that's not a detriment."

Number of U.S.-born players to feature in MLS

Even if the U.S. does qualify for the World Cup, it's going to be a problem if the percentage of U.S.-born players continues to fall. If that percentage slips into the 30s, which won't take long if the trend continues, then the aims of MLS and the U.S. might be growing too far apart. (Insert your own joke about the foreign influence in the Premier League and the struggles of the English national team here.) Already, a team like the Portland Timbers only has five U.S.-eligible players on its roster. A former MLS player put it to me like this: "The Fernando Clavijos, the Oscar Parejas and the Caleb Porters just don't think Americans are good enough."

Durbin disagreed with this sentiment. "[Domestic players] do have an opportunity and ultimately, our coaches and our teams are motivated by putting the best players they can on the field," he said. "Those players who will give a team the best chance to win are the players who are going to play."

Yes, there's opportunity, but it's also about giving players a fair chance. A player recruited from abroad represents more of an investment than a college senior or a domestic player signed off the street. The former will, understandably, get a few more shots to impress a coach than the latter. But MLS's model is also increasingly tilted toward giving domestic players more opportunities.

The league has invested millions in its youth movement. The development academies are beginning to produce talent for squads across the league, such as Kellyn Acosta at FC Dallas, Tyler Adams of the New York Red Bulls and the Vancouver Whitecaps' Alphonso Davies. The league added two more roster spots for homegrown players this season and a portion of targeted allocation money can be used to pay down their first contract (the Jordan Morris rule). Teams and coaches have an added incentive to stick with the players they have developed for longer, to try to get a return on their growing investment. Whereas an American-born player coming out of college might not get a second chance, a homegrown player from the development academy will get an opportunity that's closer to the one that a more expensive foreign talent gets.

That should help boost the number of domestic-born players and continue to pay off as the academies improve. Durbin said they are considering adding incentives to play homegrown players, with ideas ranging from additional allocation money based on the number of minutes played to adjustments in how much those players count against the salary cap. There's no timetable on these decisions, but MLS HQ is paying attention.

There's also nothing wrong with a league that has a majority of foreign-born players. What matters is who those player are.

"If you are going to go abroad and sign foreign players, which is inevitable, then sign the kind of quality who believe this is a stepping stone as opposed to a retirement league," Twellman said. "That makes the American player better. Playing with a Josef Martinez and a Miguel Almiron, where they are fighting for the same recognition as a 22-, 23-, 24-year-old American, there's a little more juice to it."

On that front, MLS is going in the right direction. In 2017, the average age of a player coming into the league from abroad was 26 years old, well below the previous lowest age of 28.5. That's a lot of young, exciting talent coming into MLS. Some of those players might take spots from an American, but they could also result in other opportunities.

"The byproduct of all this is that you get more scouts watching your product," Twellman said. "Nobody is going to watch Robbie Keane, Andrea Pirlo and Frank Lampard play at the end of their careers. Everyone is going to watch Almiron. Everyone is going to watch Josef Martinez."

When the scouts come to watch one of those players, perhaps they'll find someone else they like. Maybe they even fall for an American-born player, who subsequently gets a chance in Europe that he might not have gotten otherwise. And the cycle continues.