If I could have back all the time I've spent at racetracks in the rain and waiting for the drying process, I would be a young man today.

And I've had it easy, compared to you, the ticket-buying fan, who had to brave the elements and get home in the wee hours of Monday to go to work or maybe even throw away hard-bought tickets because you couldn't return for the rain date.

Now there's hope of considerable relief for everybody, as reported Wednesday by our David Newton from the NASCAR media tour. At Daytona in February, we can hope to see the beginnings of a revolutionary reduction of the drying process -- down to 20 percent of the current time.

Tom Pennington/Getty Images for NASCARMore efficient track-drying machinery is expected to replace the familiar jet dryers, above, beginning next month at Daytona.

Tom Pennington/Getty Images for NASCARMore efficient track-drying machinery is expected to replace the familiar jet dryers, above, beginning next month at Daytona.If this works -- well -- I cannot remember a single thing NASCAR has done, in the almost 39 years I've covered it, that would be more popular with fans, both in the stands and via television. Not to mention competitors, media and TV programming executives.

This will be no panacea. There'll always be those days of relentless downpours that force postponement.

But you and I both know the most miserable pattern there is: There's enough of a shower for NASCAR to "lose the track," as they say. Two hours or more are spent drying the track, and just as it "grays up," here comes another shower. Out come the jet dryers again to repeat the agonizingly slow process. Then another shower. And so on.

That's the sort of thing that should be eliminated with the equipment announced Monday by NASCAR senior vice president of racing operations Steve O'Donnell.

Newton reports the equipment will use compressed air in a sort of "squeegee effect," simultaneously vacuuming up water, as opposed to the current jet dryers that merely -- and oh so slowly -- blow hot air onto the track while fleets of trucks run the track, trying to blow off water with their tires.

Imagine a shower early in the Daytona 500 on Feb. 24 and the track is dry enough for racing within 30 minutes. That's what NASCAR is shooting for. They'll keep the jet dryers on site until the new equipment is perfected.

But it's an enormous start for all of us who have spent the dreary hours and days -- to me, it seems like months or years, all told -- waiting, and waiting, and waiting, and waiting.

Malign NASCAR chairman Brian France as you will -- and have -- but O'Donnell indicated France is the one who pushed for this terrific reduction in drying time. And France is asking for even more efficiency than what NASCAR Research and Development has come up with so far.

Surely you will give the third czar his due credit when his commanded achievement hits you right between the eyes -- when the green flag drops on what, half an hour earlier, was a wet track.

My first NASCAR rainout was at Talladega in the summer of 1975. The schedule being much less crowded in those days, the race was postponed for an entire week. On the rain date, Tiny Lund was killed.

I was working at an Atlanta newspaper in 1980 when there was a similar postponement for a week. It rained even more in the interim. What was then Atlanta International Raceway had grassy fields for parking lots. I called the track's then-new public relations chief for an update on conditions for the rain date.

"We'll try to have as many tractors and chains as we can to pull people out if they get bogged down," said the young PR guy.

I thought this guy would never make it in NASCAR. He was way too honest with the public.

His name? Mike Helton.

For the next 32 years, his recent decades spent as NASCAR's president, Helton more than anyone would have to endure the agony of rain and the ire of the fans.

Helton joined O'Donnell in announcing the new equipment. I wasn't there, but I've known Helton well enough, long enough, to know no one is happier or more relieved at its prospects.

Don't even think of all the time he has spent in the rain at tracks, trying to figure out what to do, knowing nothing he can decide will please the public.

Just take the time Helton has spent standing in the door of the NASCAR hauler looking helplessly out at the rain. If he could just have that back, there would be no gray in that mustache.

Karen Bleier/AFP/GettyImagesBlack bears (Ursus americanus), such as this one in Virginia, can be a common site -- and sometime nuisance -- across North America.

Karen Bleier/AFP/GettyImagesBlack bears (Ursus americanus), such as this one in Virginia, can be a common site -- and sometime nuisance -- across North America. JASPER, Ga. -- Except for Friday's "big one" at Daytona, NASCAR has largely been in hibernation lately. The black bears of the north Georgia mountains have not.

Last time I wrote about the majestic animals that seem to love my little piece of the Blue Ridge, readers complained that surely there must be something going on in NASCAR that would trump news of bears.

But, our David Newton having reported and analyzed the 12-car pileup in winter testing, you'll pardon me for getting worked up over another kind of big one entirely -- a 250-pound pregnant female taking up residence under my deck.

Besides, we're always writing about what drivers did on their winter breaks -- sunning in the Caribbean, or going on charity missions -- so why can't I tell what I did?

This bear's intentions were clear: to make this her maternity ward and then a nursery and pediatric center through, oh, about March. That could put me at Daytona for Speedweeks at the time of the blessed event.

With all due respect to the celebrated pregnancies of various NASCAR wives in recent years, this one promised more impact on me personally. You see, each member of the species Ursus americanus considers its place of birth its home for life -- and our game wardens up here have seen bears up to 27 years old. I've spent the past two years dealing with one such family that considers mi casa their casa. Another generation would be just too much (to) bear.

We think this particular bear might be the one my late wife named Ella -- not for Jeff Gordon's daughter but for the next town north of here, Ellijay. Or it might be Ella's daughter, all grown up now and yearning for a family of her own.

At any rate, Ella or Young Ella came to precisely the same spot under the deck where the first family was born, and she settled in -- sort of. If only she'd lapsed into a long, silent winter's nap, that would be one thing. But the black bears of the Blue Ridge don't really hibernate -- they take naps of weeks or days, then stir, then nap again. Or, they settle in to bear a litter, but don't sleep throughout.

As Ella grew uncomfortable and restless, we could hear wood breaking and crunching as she chewed and clawed out more comfortable digs for herself. Put it this way: my deck was once supported by two-by-10 joists. They are now two-by-fours, thanks to Ella's remodeling.

Late in the afternoons and at night, we could hear her working. At one point it sounded as if she were going to tear through the walls and come out on the stair landing.

On New Year's Eve, my son, home from law school, went to Atlanta to party with friends in Buckhead. So here we were, just the two of us, Ella and me, with only a wall separating us, and Ella seeming intent on tearing more of that out.

I wasn't afraid of her. Bears cross my property routinely -- a big male lumbered along the ridgeline, out my kitchen window, on almost a daily basis back during mating season, and a sow and three cubs were headed straight into my garage before I closed the door, just in time, a few months ago. (They didn't look angry about it, but their feelings seemed hurt that they were not invited in.)

But Ella was doing damage beyond remodeling the underside of my deck. She'd torn two huge holes in the wire mesh and lattice work of the sub-decking. A propane gas line is so close to one of her entrances that I was warned she might crimp the line, cutting off my heat at best -- or causing a dangerous leak at worst. And as she stirred in her sleep, she was scratching her back against the area where the house meets the foundation, gouging out little gaps for smaller critters -- squirrels and chipmunks -- to get inside and nest.

Finally, in midafternoon on New Year's Eve, I phoned the Georgia Department of Natural Resources. I didn't even expect to get an answer during the holidays.

Which brings us to the story of one state agency that works, that does its job above and beyond the call, with great courtesy, patience and humaneness. If all agencies in all states worked as well as my region of Georgia DNR does, there would be no complaints about government bureaucracy.

I was hoping to get game wardens up here within maybe a week at best. Ronny Holcomb, the duty game management officer for this area, said he could come up here the very next morning, on New Year's Day.

A cold rain was pouring as Holcomb, with 20-plus years' experience at dealing with bears, shone a powerful flashlight down through the cracks between the boards. "One bear, looking at me," he said. But his view was obstructed so that he couldn't tell whether she already had a cub or not.

He would consult with Mitch Yeargin, North Georgia's most experienced bear management officer, and with state bear biologist Adam Hammond. They would all come out together to evaluate. We agreed that if she hadn't had her litter yet, they might encourage her to move on. If she already had cubs, she could stay till spring.

And so, on the morning of Jan. 7, I had a lot more on my mind than just the Alabama-Notre Dame BCS championship. If Ella already had a family, she would be my gnawing, clawing, 250-pound guest till March at the earliest, and her offspring would consider this their home for perhaps decades to come.

It was Yeargin, who'd been up here before, during construction of the house, who suspected that this was either the mama or a daughter of the original family. Hammond, the biologist, had the call on whether Ella would stay or be encouraged to move.

Upon close assessment, they saw no cubs. Hammond popped a tranquilizer dart into Ella's flank, and all three officers stood ready, the game wardens with their hands on their sidearms, just in case. The wire mesh under the deck began to shake, and here came Ella -- not charging, just loping out, as if to complain about being bothered.

She is too big for a tranquilizer dart to bring her down. Merely woozy, she continued to lope along the ridge line and then over it. The game officers followed her for, I suspect, nearly a mile along the mountain, hoping Hammond could place a radio collar on her.

But Ella just kept going. Yeargin's experience told him the morning had been so stressful on her that she probably won't return. Hammond placed a digital wildlife camera near Ella's favorite entrance, just in case.

There is a cave just across a stream bed from my house that has always seemed to me a perfect dwelling for bears. Holcomb went in to explore it, and came back certain it had indeed been a haven for Ursus americanus, for thousands of years.

But that was before development.

Now, human structures have become more convenient than the caves. Worse -- much, much worse, some humans are na´ve enough to feed the bears.

I pointed up the mountain toward another residence, where a neighbor once had told me he used to feed the bears.

Holcomb pointed underneath my deck. "That's not your problem," he said. Then he pointed up the mountain: "That is your problem."

I never put out bird feeders (aka bear popcorn) or use an outdoor grill. But because some do, human dwellings have become associated with human comforts, human food. If one house feeds, the bears are attracted to nearby houses as well.

"We try to tell people, 'A fed bear is a dead bear,' " said Yeargin, who recently, heartsick, had to put down two bears from another development because they'd become dependent on feedings, and turned dangerous.

Ella and her offspring, for generations to come, would be welcome to live in my cave, and forage for themselves. I miss her already, but don't miss her thumping and scratching at night.

So I didn't go to the Caribbean, or on a cruise to Alaska. But I did have a different kind of NASCAR offseason.

TALLADEGA, Ala. -- Here at Casino de Alabama, for the least predictable and most broadly decisive race of the season, Dale Earnhardt Jr. is taking a deep breath, placing both hands around all his chips and pushing them forward.

For him, in the Chase, this is it.

That's how he's treating it.

"We can't be conservative at all," Earnhardt said of Sunday's Good Sam Roadside Assistance 500 (2 p.m. ET, ESPN). "We've really got to take a lot of risks."

Going into the fourth of 10 playoff races, Earnhardt is seventh in the standings, 39 points behind leader Brad Keselowski, 34 behind second-place Jimmie Johnson and 23 behind third-place Denny Hamlin.

That's not where Junior Nation, or its leader, hoped he would be at this point. This, they figured, was his best shot at a championship since the inaugural Chase of 2004.

That's the year he last won at Talladega Superspeedway. Now he'll go with the all-out style that dominated here earlier this decade, when he won five of seven races, including four in a row.

Todd Warshaw/Getty Images for NASCARDale Earnhardt Jr. has only one top-10 finish through the first three Chase races -- an eighth at Chicagoland.

Todd Warshaw/Getty Images for NASCARDale Earnhardt Jr. has only one top-10 finish through the first three Chase races -- an eighth at Chicagoland."As good as everybody is running, like Brad and Jimmie and the No. 11 [Hamlin], we really have to get pretty aggressive, and that should play right into this racetrack's hand," Earnhardt said. "It's a place that really kind of asks for that, and you've got to really take some risks and be pretty daring out there to make some things happen."

And if the daring backfires?

"We're in a position where it really doesn't matter," he said.

Either "the big one" happens to him or it doesn't.

"Sometimes it happens with the usual suspects, and sometimes it's a surprise of even who would be involved in it," Earnhardt said.

"I've been on the receiving end of some wrecks here, and I've started a few myself."

Much as the chaos of this place is ballyhooed going into every race here -- especially the fall race, when the Chase can be scrambled seriously -- it's sometimes hard to keep the following truth in mind.

"Somebody's going to win this race," Earnhardt said, "and I want to be that guy."

Keselowski, Earnhardt's friend and former employee at JR Motorsports, and his Penske Racing team have the most to lose in a scramble of the standings.

But, typically breezy, "I'm going to look at it positively and think that if I do everything right that there's a chance I could leave here and have a really big points lead," said Keselowski, who won the race here in May.

Sunday night, after the finish of the only restrictor-plate race in the playoffs, the Chase promises to offer a clearer picture.

"You really kind of find out what your chances are going to be for the championship once you leave here," Hamlin said. But he can't see his chances being completely wiped out here, either.

"No matter what the result for us, I think we're still going to be in it," Hamlin said, because "we're not back more than a race [in points] already."

Jeff Gordon, who barely made the Chase at Richmond and fell back badly in the playoff opener, sits in 10th place and, like teammate Earnhardt, has nothing to lose.

"I'm excited," Gordon said. "That's the first time I can say that in a long time coming into a Talladega race because, for us, it's not about racing for points, it's about racing for a win and being aggressive."

Most drivers say they don't make a decision until the race starts whether to lag behind and try to avoid the wrecks that way or run up front and try to keep the wrecking behind them.

"There's not really a right or wrong in this situation," Earnhardt said. "But for me, I feel more comfortable just being aggressive all day."

When, six years ago, Chris Economaki finally agreed to publish an autobiography, I was asked to write a dust-jacket blurb. It bears repeating now, on the day of his death at nearly 92.

"Anyone worth a damn in motorsports journalism -- and I mean anyone, electronic or print -- who doesn't acknowledge Chris Economaki as his or her mentor is either a liar or a fool," I wrote. "I proudly and dearly claim the man as my inspiration 32 years ago when I started, my inspiration today, and my inspiration for whatever remains of my career.

"If there is a heaven, I mean to spend my first thousand years there listening to Chris tell stories. And that will only amount to happy hour."

The six years from then 'til now have moved so swiftly that there is now a generation of motorsports media who didn't even know Chris personally. But I state firmly to them now: You may not hold him as your father in this business, but he remains your grandfather, whether you realize it or not. You were taught, and given standards, by those he taught and gave standards.

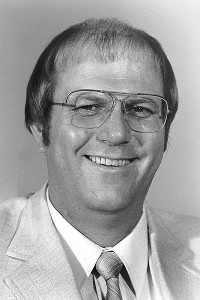

Getty ImagesIf it was happening at a race track, Chris Economaki, right, was likely there.

Getty ImagesIf it was happening at a race track, Chris Economaki, right, was likely there.He was the very first of our lineage, and he will remain the greatest, always.

His was God's own voice, with a sharp crack of thunder in it, to all the world's motor racing: NASCAR, Formula One, Indy cars, sports cars, drag racing -- he was a walking, always talking encyclopedia of it all.

"Many people consider Chris the greatest motorsports journalist of all time," NASCAR chairman Brian France said in a statement from Daytona Beach.

Count me in that legion, absolutely, positively.

Why the man who never seemed to sweat in his ABC Sports blazer took an upstart kid under his vast wingspan in 1974, I will never quite understand. But I am ineffably grateful that he did, that he taught me how to be thorough in reporting and gave me self-confidence as a writer.

Perhaps he sensed I was as consumed with this stuff as he was. We bonded right away, exchanging the stories of how we were drawn to the once-taboo sport of automobile racing in the first place. His was from New Jersey in the 1930s and mine from Mississippi in the 1950s, but the themes were identical.

As a child, "I would hear this tremendous roar coming across the trees from the track," he told me. "I wanted to find out what that was. They were called, simply, 'the racing cars,' in those days.

"And that roar was a siren song to a boy."

A siren song. Precisely. Just as the "old stock car races," as my mother called them in disgusted explanation of what I was hearing from the fairgrounds, were to me.

The siren song lured Economaki all around the world, for ABC, CBS, ESPN and TBS, and all the while he edited the bible of all racers in the U.S., the National Speed Sport News.

He began as a boy hawking copies of the direct predecessor of Speed Sport at the tracks, then began reporting, writing and announcing at tracks before moving to television.

"The crowd," he once told me, "should never leave a track having seen nearly as good a race as it thinks it has seen. And that is the job of the track announcer."

When you think about it, they all go by that now, from track P.A. systems to live national television, and therefore they are all descendants of Economaki.

Never once, in any conversation at the tracks or in the bars, could I bring up the name of a single driver, anywhere, that Chris didn't have a story about.

When finally he published his autobiography, with Dave Argabright of Indianapolis, they called it "Let 'Em All Go!" after an old short-track promoter's gimmick line. A mutual friend of ours from Economaki's TBS days, producer Chet Burks, always thought the title should have been "You Had to Be There," and I agreed on that.

Often, Economaki would begin a story to me, "Eddie, you had to be there …" and then make me feel I really had been there.

And that was the genius, and the essential greatness, of Chris Economaki.

Jerry Markland/Getty Images/NASCARCarl Edwards, who lost the 2011 Cup championship on a tiebreaker to Tony Stewart, might not even qualify for the Chase in 2012.

Jerry Markland/Getty Images/NASCARCarl Edwards, who lost the 2011 Cup championship on a tiebreaker to Tony Stewart, might not even qualify for the Chase in 2012.HAMPTON, Ga. -- Deep into must-win mode now, Carl Edwards has been doing backflips -- and cartwheels, and somersaults -- all weekend here.

They've been verbal, not physical, but plenty animated. His enthusiasm has gushed for Atlanta Motor Speedway, a track so suited to Edwards and his current dire needs for making the Chase that ... well ...

"If the Lord were to take me from this earth right now, there would be a place in heaven that would look a lot like this racetrack," Edwards said Friday.

He is 12th in points but seventh in the dogfight for that final playoff berth, because he doesn't have a win and five drivers who are behind him in points do.

So he badly needs a win here Sunday night in the AdvoCare 500 (ESPN, 7:30 p.m. ET), and a win next week at Richmond really wouldn't hurt. But the season has gone fitfully for Edwards' No. 99 branch of Roush Fenway Racing, while teammates Greg Biffle and Matt Kenseth are first and fourth, respectively, in the standings and comfortably in the Chase.

If his back must be to the wall, "We could not be at a better racetrack," Edwards said. "This track is as good as it gets. Driving practice out there was a blast. I love this place for a number of reasons [e.g., he got his first Cup win here, in 2005], but right now, this is the type of track we need.

"We need a place you can hang the car out. Fresh tires will be faster than old tires [there's still major tire 'falloff' here]. There will be a lot of passing.

"There's definitely three to four and maybe even five grooves out there."

AMS is beloved by the consensus of drivers, not only because it's so wide, so accommodating to running just about wherever a driver chooses, but because of "how wore out this place is," as Dale Earnhardt Jr. put it, "and how the tires go away real fast. It's definitely a different style of racing, something we do less and less of. It's definitely welcome by most drivers out there."

Tyler Barrick/Getty ImagesWhy is Tony Stewart smiling? Because he's sitting on the pole for Sunday's AdvoCare 400.

Tyler Barrick/Getty ImagesWhy is Tony Stewart smiling? Because he's sitting on the pole for Sunday's AdvoCare 400.Jeff Gordon wholeheartedly agreed about the surface, which hasn't been repaved since 1997.

"This place is old, worn out, cracks everywhere, and yet every driver loves it," said Gordon, who made his first Cup start here 20 years ago this fall. "We're slipping and sliding around. The racing is pretty spectacular."

Attendance issues have cut Cup racing back to once a year here, but, "from a surface and pure driving-on-the-track standpoint, I'd like to come here five times a year," Gordon said.

Still, Edwards' verbal handsprings topped the competition of praise, understandably. Room to roam on a racetrack is precisely what showcases Edwards' risk-taking driving style.

"This track is one where you can drive the car sideways, you can take chances, you can burn the tires off for three laps and make it look good and get yourself in a position to do something spectacular," he said. "You could maybe bend that car around the corner a little harder and make something happen if you want to.

"I'm ready for that."

And desperate for that, if he is to make the Chase.

So here we are, running 140 mph into the first turn at Indy in a Dodge Viper and Carroll Shelby is driving, his head turned toward me, running that mouth in that gravelly Texas twang.

He's driving with his left hand and gesturing with his right, not even looking at the track, let alone that turn, which, though banked only 9 degrees, looks like a mountain rushing at you when you're heading for it at speed.

"A.J. Foyt couldn't design a s---house," is one topic he touches on near the end of the front straightaway, and then, "Jim Hall was the smartest kid I ever hired outta Caltech …"

This is the man who fathered the Cobra sports car and all the various Shelby Mustangs and Shelby Dodges, the commanding general of Henry Ford II's frontal assault on, and triumph over, Enzo Ferrari at Le Mans in 1966 and '67.

This is either the most rough-hewn genius or the most brilliant Texas redneck who has ever lived, and he keeps grinding stories out like a cement mixer at 140 mph.

And I'm thinking, "Lord, just let this old man with the transplanted heart look at the frigging corner before we get there," but he doesn't, and Bobby Rahal's words flash to mind: "There's no amount of money in the world that can make you go down into that first turn at Indy and turn left unless you WANT to."

This isn't about money or desire, it's just a lark, just a ride for the helluvit, and Carroll Shelby is laughing, looking at me, and suddenly it hits me, to my great relief:

Nothing to worry about. Carroll Shelby cannot die.

If he could, he would have been dead for 50 or 60 or 70 years by now.áHe's had heart problems since age 7.áHe had a transplant in 1990, maybe five years before our little excursion here.

Whomp! The Viper takes a set, and we pull some G's, but Shelby still hasn't looked away from me and he's still pouring profanity, telling his stories.

Back in the pits, I, in my 40s, feel certain that Carroll Hall Shelby, at that point in his 70s, will easily outlive me.

Well, I'll be damned.

Carroll Shelby died Thursday, May 10, 2012.

He was 89. He lived 82 of those years with heart trouble, the last 22 with a transplant. He had lived wide open, full of piss and vinegar all the way.

I'll be damned. Toughest SOB of a genius I've ever known.

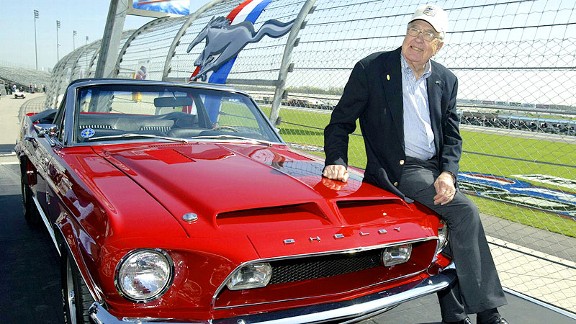

JEFF HAYNES/Getty ImagesCarroll Shelby sitting on a 1968 GT500 KR during the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Ford Mustang in 2004.

JEFF HAYNES/Getty ImagesCarroll Shelby sitting on a 1968 GT500 KR during the celebration of the 40th anniversary of the Ford Mustang in 2004.Oh, honey, hail! Hail! The gang's all here

For an Alabama jubilee

George Cobb and Jack Yellen, 1915

TALLADEGA, Ala. -- Silly me, I thought there would be one car here Sunday that could draw a mightier roar from the grandstands than even the No. 88 of Talladega Superspeedway's unanimously adopted son, Dale Earnhardt Jr.

That would be the No. 15 of Clint Bowyer, liveried in the colors of the Alabama Crimson Tide, reigning national champions of college football. Last spring here, Michael Waltrip carried the orange and blue of the 2010 champion Auburn Tigers.

Tom Pennington/Getty ImagesCrew members work on the No. 15 Aaron's/Alabama National Champions Toyota of Clint Bowyer in the garage area during practice.

Tom Pennington/Getty ImagesCrew members work on the No. 15 Aaron's/Alabama National Champions Toyota of Clint Bowyer in the garage area during practice.I figured even the War Eagle legions would cheer the crimson and white Sunday out of sheer state pride -- no other has produced three consecutive national champions. For that reason, even my son, an Auburn graduate and adoptive Alabamian, pulled for the Tide against LSU in the BCS Championship Game.

Bowyer, who has won two of the last three races here, will even wear a helmet bearing the visage of Bear Bryant.

"If Earnhardt wins, it'll be 100 percent [cheers]," said Huntsville Times columnist Mark McCarter, a buddy of mine who always has his finger on the pulse of the Alabama public. "If Bowyer wins, it'll be 50-50."

Not even that, reckoned Talladega Superspeedway chairman Grant Lynch, who proceeded to give me an astounding lesson in the demographics of his crowds. Turns out Talladega is a wide gathering of Southeastern Conference tribes.

Both Alabama coach Nick Saban and Auburn coach Gene Chizik, who served as grand marshals for the spring race in 2009 and 2010 to celebrate national championships, were booed.

"Saban got booed a lot more when he was grand marshal than Chizik did," Lynch said. "And they both were amazed that they were being booed as much as they were. I told both of 'em, 'Listen, this isn't just Alabama. I got LSU, I got Tennessee, I got Georgia, I got South Carolina, I got all the people here.'

"I said, '75 percent of my fans come from outside the state of Alabama. Half of them come from more than 300 miles away.' LSU -- in the infield, they're probably No. 1. You go down Talladega Boulevard, you'll see more purple and gold than just about anything. And even out in the campgrounds, they're huge."

Among Alabamians who attend, Lynch figures the breakdown is about 55-45 Alabama over Auburn.

Both of Lynch's daughters are Auburn graduates, and the youngest will officially "walk" Sunday -- but across the stage here rather than at Auburn.

"Sara Katherine called me and said, 'Daddy, I graduate on your race weekend, either Saturday or Sunday,'" Lynch said. "And I said, 'If it's Saturday, I can probably get down there. If it's Sunday, I can't come.' She called me back and said, 'It's Sunday. I just won't walk.'

"I said, 'Yeah, you'll walk. I got a stage here at Talladega.'

"I thought, 'I sell tickets to everybody and I'm not going to make anybody mad, so let's get an Alabama graduate up there too.'"

They found an Alabama graduate school student who had already decided to "walk" here on a stage rigged by his buddies, and now he'll cross the Talladega stage with Lynch's daughter.

War Eagle! Roll Tide!

But at this Alabama jubilee, add Geaux Tigahs! Go Dawgs! Go Vols! And allow for some Hogs, Rebels, Gators and Gamecocks too.

I agree with many NASCAR pundits that Anne Bledsoe France shouldn't go into the NASCAR Hall of Fame in the fourth group. I think she should have gone in before her husband, NASCAR founder Bill France Sr., and her elder son, the second czar, Bill France Jr.

I think she should have gone into the Hall of Fame before there was a Hall of Fame. They should have laid a cornerstone with her name on it before they even started construction of that building in Charlotte, because she WAS the cornerstone of NASCAR.

ISC Archives/Getty ImagesAnne B. France's influence on NASCAR was immense, because she was the one keeping track of the money.

ISC Archives/Getty ImagesAnne B. France's influence on NASCAR was immense, because she was the one keeping track of the money.From day one there should have been an "Annie B. Room" near the main entrance. In the room, there should be a simple desk, and on it should lie an adding machine, an old-fashioned bookkeeper's ledger, a few cigar boxes filled with cash (they could use Monopoly money lest the patrons help themselves) and a pair of glasses.

On the wall behind the desk there should be an elegant sign, carved in oak: "Without Her, There Would Be No NASCAR."

Lesa France Kennedy, who at age 14 was apprenticed to her grandmother, will tell you Annie B. kept two sets of books during and beyond the formative years of NASCAR and Daytona International Speedway.

"There was the real set," says Kennedy, now CEO of International Speedway Corp., "and then she had one that she would show my grandfather."

Whatever Big Bill knew he had, he would spend.

Betty Jane Zachary France, Bill Jr.'s widow and Brian and Lesa's mother, recalls arriving as a new bride in Daytona Beach and being put immediately to work with Annie B., bookkeeping.

At the end of one day, young Betty Jane was 10 cents off on her ledger. Oh, well, she would just figure it out the next morning.

"You're not going to leave," Annie B. told her new daughter-in-law.

"She made me stay," Betty Jane remembers. "I cried. I went home and told Bill [Jr.], 'I can't work for this family, I can tell you right now.' He said, 'Well, that's how she is. You'll get used to her.'"

All of NASCAR did. There was no choice. If Big Bill ruled with an iron hand, Annie B. ruled by the life's blood, money. She was not just his helpful wife. She was his boss.

First time I walked the halls of the old NASCAR building, as a rookie reporter in 1974, I was being shown around by a tough old publicist of the time. He gestured toward an open office door, and there she sat in those glasses, alone, silent, poring over financial statements.

"That sweet little lady," he said, "knows where every g------ dollar in this organization is, where it came from, and where it's going."

Every France and France associate I've ever told that story responded the same way: "Absolutely."

I'll have much more on Annie B. in a saga of the France family, a series I'm developing for publication here on ESPN.com later this year. Suffice it to say for now that no one I've interviewed thinks there would be a NASCAR today without her.

She was a nurse by profession and had met Big Bill France at a dance in Washington, D.C. She married him in 1931 and in '34 packed up all their belongings for his impulsive drift down the Eastern Seaboard in search of a better life. They liked Daytona Beach, knew about its racing history since 1903, and stopped, and stayed.

The rest is history in which Annie B.'s name rarely appears. She took a bookkeeping course at a local business college, and from there she literally knew where every dollar in NASCAR was, and hid a helluva lot of it from her husband so he wouldn't spend it.

She had Big Bill on an expense account. Whenever he went off on a trip, say to Alabama to look at land for a new speedway or to meet with Gov. George Wallace, Big Bill had to submit receipts for everything -- meals, hotel rooms, fuel for his private plane -- or he simply did not get reimbursed.

After one beach race, before the big Daytona track was built, the legend-to-be broadcaster Chris Economaki happened by the little France bungalow near the Halifax River late on Sunday evening.

"Bill answered the door, but didn't invite me in," Economaki once told several of us. "That was very unusual -- he was always very friendly and hospitable. On this evening he was very nice, but he stood in the doorway with the door opened only a couple of feet.

"I got a glimpse inside. There were stacks of money, cash, everywhere on the floor. And in the middle of all that money sat Annie B., on the floor, counting."

The Frances now are all millionaires many, many times over. So are a lot of NASCAR's owners, drivers, even crew chiefs. Every one of them has that little lady to thank profoundly.

Among the statues at Daytona now, tallest of all, rises the 6-foot-5 likeness of the founder of NASCAR, but he is not alone. He has his arm around the bronze likeness of a diminutive woman. There's a damn good reason for that.

The moment confirmation came out Wednesday that Bristol Motor Speedway will indeed bow to fans and -- how do you put this? -- re-reconfigure the track, I thought immediately of the best friend NASCAR fans ever had, the late Jeff Byrd.

No one on this planet cared more about you, who pay your hard-earned money for tickets, than he did.

"JayByrd" was the track president who had Bristol redone in 2007. He was the one who took the blame for it, and felt so bad about it, until the day he died in 2010, at age 60, of brain cancer.

I thought of the wee hours in the parking lot at Bristol after the 2008 night race, the first one that laid a blatant egg, on the new surface, widened from the old one.

Byrd drove a golf cart around, stopping at each straggling gaggle of fans and saying, simply, "Y'all, we're sorry."

As he drove toward a group of reporters, I shouted jokingly at him:

"JayByrd! Have you overnighted Carl Edwards his certified check for a million dollars for saving your event?"

Kyle Busch had dominated, leading 415 consecutive laps so smoothly, that David Poole of the Charlotte Observer, also gone now, dubbed the place anew: "Mini-Michigan."

But at the end of the race, Edwards had taken Rowdy out to win, and there had ensued a slamming match on the cool-down lap that -- finally, finally that evening -- satiated that traditionally enormous "Bristol Night Race" crowd.

So, I kidded, had Byrd compensated Edwards?

Byrd got out of his cart, walked over to me, put his head on my shoulder and cried out loud.

He was half-kidding, but half-serious.

"Do you think Carl saved my job?" he said as he mock-sobbed.

Byrd knew that night he'd made a mistake that would be hard to undo. Knowing the man as I had since 1974, I can assure you that he was sorrier for you the fan than for himself, as the BMS president who had to answer to track-owning mogul Bruton Smith.

Byrd's full intentions were to make the racing better for the fans. That you were displeased made him heartsick.

Smith didn't go into details Wednesday about what will be done to the track, whether an attempt will be made to return it exactly to the Bristol many of us thought was the best and most action-packed track on the tour.

The details will come later, but …

"The race fans have spoken," Smith said in a statement.

But Byrd had heard you that hot August night nearly four years ago, and he told you up front that he was sorry.

If he hadn't gotten sick, I suspect he would have moved sooner.

So please don't feel vindictive now that Bristol has yielded.

Just know that your late dear friend meant well by you.

Getty ImagesBenny Phillips, center, is flanked by other members of the media, from left, Jim Hunter, Gene Granger, Gerald Martin and Randy Laney at Atlanta International Raceway in 1973.

Getty ImagesBenny Phillips, center, is flanked by other members of the media, from left, Jim Hunter, Gene Granger, Gerald Martin and Randy Laney at Atlanta International Raceway in 1973.

Benny Phillips was the grit and the guts of the NASCAR media corps for more than 40 years. It was he who dubbed Darlington Raceway "The Lady in Black."

He was the writer Richard Petty trusted most down through the decades. He co-authored Dale Earnhardt's autobiography. He so captivated Formula One legend Ayrton Senna upon their first meeting that the great Brazilian shooed away all his handlers and gave the North Carolina reporter all the time he needed.

Outside racing, Benny had enough narrow escapes from death in the outdoors to rival big-game hunters and soldiers of fortune. Countless cowboys, backwoodsmen, poachers, bootleggers and hunting guides called him a friend.

Benny died Tuesday, at 74, in the last kind of place he wanted to -- a hospital.

He had tumbled ATVs down mountainsides, been thrown off horses, fallen out of tree stands, saved panicked friends in small boats in winter tempests off the Outer Banks, had a skiff go upside down on him in a raging, freezing river …

Oh, one other thing: Benny was a paraplegic.

The Salk vaccine came one summer too late for him. Benny always reckoned he'd contracted the polio virus in a country swimming hole, the way so many kids did in the 1950s.

You get an almost certain path to Duke or Chapel Hill as a running back cut off suddenly, completely, you're pretty ticked off. And Benny was, but only for a little while.

He went off to Warm Springs, Ga., to the therapy center established by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and encountered an old Marine Corps gunnery sergeant who'd been shot through the spine in the Pacific.

Just as Benny got his bearings with steel braces on his legs, the gunny would sneak up behind him and knock one of his crutches away.

ISC Images & Archives via Getty ImagesBenny Phillips was selected the National Motorsports Press Association writer of the year seven times and spent 48 years with the High Point Enterprise in North Carolina, ultimately serving as sports editor for 32 years.

ISC Images & Archives via Getty ImagesBenny Phillips was selected the National Motorsports Press Association writer of the year seven times and spent 48 years with the High Point Enterprise in North Carolina, ultimately serving as sports editor for 32 years."You're gonna fall," the gunny would say. "You're gonna fall a lot for the rest of your life. Might as well get used to it."

All those years Benny traveled the Cup tour, he never would accept a room fitted for the handicapped. All that stainless steel stuff got in his way. He'd been taught by the gunny to "improvise; improvise; improvise."

For 40 of the 48 years he wrote for the High Point Enterprise, all 27 years he wrote for Stock Car Racing magazine, even his 12 years with Turner Broadcasting, Benny "walked."

That's what he called lumbering along on crutches through the garages and through airports and onto planes.

Seven times he was National Motorsports Press Association writer of the year. He deserved the Henry T. McLemore Award, given for courage in auto racing journalism, more than any other winner.

ATVs, which he discovered in the 1970s, set him free to hunt, from the quail fields and turkey thickets of the South, up to Montana and even on up to Hudson's Bay in Canada.

But for all those decades he never would abandon those crutches and heavy steel braces for a wheelchair. The braces almost took him under once, when a boat capsized on him while he was duck hunting on a river.

When he went to interview Senna for TBS, Phillips and his crew were told they had 15 minutes. Senna was a deeply caring and sensitive man, virtually a priest, and so immediately he told Benny he didn't mean to be nosy but wanted to know what had happened to him.

Benny told him. Senna said he had a sister who'd been disabled by disease. Before they knew it, the McLaren publicists came and told Benny the interview time was up. Senna told them no. To go away. That they would take as much time as they wanted.

Maybe 10 years ago, the cartilage in Benny's shoulders just wore out from what he called "40 years of walking on them." Finally he yielded to years of advice from his doctors to get into an electric wheelchair.

I called it his scooter. He was hell on it, just as as he'd been on the ATVs in the mountains and fields. More than once he turned the scooter over, one time suffering a compound fracture of a leg.

This winter, hunting, Benny was injured just trying to get onto the scooter, and needed surgery. The aftermath didn't go well, and besides, he was seriously diabetic by this point.

He fought the complications for more than a week in intensive care. But this time all the grit and all the guts weren't enough.

For 37 years he was one of my closest friends. He taught me much about motorsports journalism, even more about the ways of animals in forests, birds in fields and fish in streams.

And we played a helluva lot of poker.

I am heartsick.