Garrett Ellwood/NBAE/Getty Images

Garrett Ellwood/NBAE/Getty ImagesSpurs like Aron Baynes had some high-tech gadgetry under their jerseys at Vegas Summer League.

"Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us ..."

-- F. Scott Fitzgerald

It all started with a little green light.

On the first night of the NBA's summer league in Las Vegas, the San Antonio Spurs played the Charlotte Bobcats. As Spurs center Aron Baynes prepared to inbound the ball from the baseline, a small green light was visible, blinking steadily through the white mesh of his jersey.

First question: Is he a cyborg?

Second, more sensible question: Is that the biometric monitoring the Spurs have used in the D-League?

A stroll behind the bench confirmed every Spur had a small bulge, just between the shoulder blades, blinking green.

Fascinating. Mysterious. And as it turns out, loaded with potential: It's part of a system that has led to a huge reductions in injury, and dramatic improvements in performance, in a professional league half a world away.

After the game, the Spurs communications staff opted to "politely decline" the opportunity to talk about the green light.

We learned from 48 Minutes of Hell’s Andrew McNeill that the Austin Toros -- the Spurs’ D-League affiliate -- were trying out some technology made by Catapult Sports.

"It’s a load meter and it’s a new sports science thing," Toros coach Brad Jones explained to McNeill. "It's like a vest you put on underneath [your clothes] and you wear it in practice and it keeps track of the energy you’re burning."

The key term here is "load," the aggregate energy put into and stress placed upon the body during athletic activity. In basketball terms, this may mean -- according to the Catapult Sports site, which confirms the Spurs as clients -- measuring "the speed of a shooting guard coming off a down-screen, the impact force of a center banging on the low block, or the total distance covered by a point guard over the course of a game, week or season."

Was this what the Spurs were wearing? An article on the company by Forbes’ Alex Konrad noted that "[w]earable sensors are still banned in the U.S. during official game play."

Konrad put us in touch with Catapult's Gary McCoy who, it turned out, was in Las Vegas, ready and willing to sit down to talk about what Catapult Sports does.

An Australian company, Catapult Sports first began working with Australian Rules Football, and McCoy makes some impressive claims about the company’s effectiveness there. “Where we’re at with sports science in Australia," he told Lynch, "is that we’ve reduced injury by almost 30 percent, and we’ve increased outputs by almost 25 percent." These numbers come from the extensive injury research the Australian Football League conducts (see, for example, this 2012 report) and from the company’s own measurements of an increase in fourth-quarter speeds and accelerations. The net effect for these athletes has been to "extend and enrich a player’s career. That window is always closing on you, whether you’re a team or a player.”

The way McCoy talks about the company reflects Catapult Sports’ core mission: to maximize athlete effectiveness by minimizing injury and the deleterious effects of exhaustion. “We’re getting questions from one of the biggest profile [NBA] teams that has an aging athlete,” McCoy said. “And one of the questions coming from their training staff was, ‘Can we look at his physiological matrix and what makes up his exertion level and know that we might have to pull him every six minutes or so to sustain his output in the fourth quarter?’”

How to extend an aging athlete’s career is a vital question as teams work with players like Tim Duncan, Kevin Garnett and Kobe Bryant, but it can be just as important for younger players to start making the most of their bodies now.

The directions players move have a surprising amount to do with injury prevention. McCoy refers to this as asymmetry, and it’s something most basketball fans know: athletes often move better in one direction than the other. When someone says, “Force him left” or, “Don’t let him catch it on the right block,” this is what they’re talking about.

“It’s just like wheel alignment in a car,” McCoy said. “It impacts return to play [from injury]. We had a very prominent NBA player’s ACL rehabilitation we measured last year. Phenomenal athlete. Left ACL was the rupture." Catapult is constrained from discussing its clients, but a survey of injury reports shows Derrick Rose, Danilo Gallinari, Ricky Rubio, Iman Shumpert, Nerlens Noel and Leandro Barbosa to be among those who have torn left ACLs in recent years. Rajon Rondo also suffered a partial tear. "And [the training staff] said 'Based upon strength, we think he’s close to being ready.’ When they actually measured him with a Catapult device, they could see his accelerations to his right were at about a 60 percent deficit off of his left leg compared to what they were to the other side. And you can’t see this stuff with the naked eye.”

Injury rehabilitation has long been a dark art in professional sports, with players assigning whole number percentages to how ready they are based on feeling. Adding a level of precision to the measurement of strength and stress under different conditions isn’t the entire answer, but it’s still a step toward a clearer understanding of each athlete’s unique timetable for recovery. A player might feel 85 percent ready, but with what degree of confidence can that number be trusted?

Catapult can also help indicate when an athlete’s movements simply aren’t that efficient. There are players who expend a lot of energy on the court -- the “hustle guys” -- even if they’re not scoring. But what if they could do their job more efficiently? “I often refer to the Catapult monitor that we place on the athlete as ‘the little orange jockey,’” McCoy wrote in an email. “Take him for a nice ride,” he tells the athletes. “The more that unit is bouncing around -- the less efficient the athlete’s movements are -- the more it’s increasing their individual load.”

McCoy has worked with Toronto Raptors trainer Alex McKechnie and a player like Rudy Gay, whom McCoy cites as one who “appears to glide effortlessly,” gives the monitor a smoother ride. As a result, his total load might be less than another player, but it doesn’t mean he’s working less. He’s just doing his job with greater economy of movement. Of course, the Catapult monitor can’t tell you anything about Gay’s shot selection, but just as analytics confirmed strategies about the value of the 3-pointer or free throws, the system can help bring evidence to what trainers like McKechnie often sense intuitively.

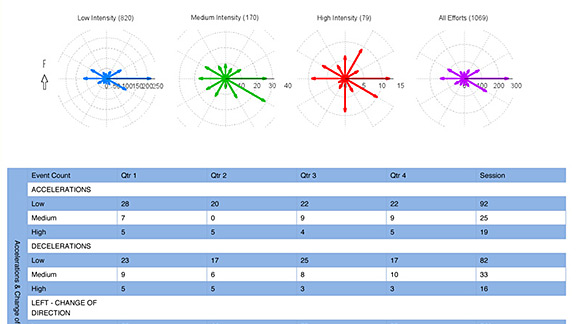

Courtesy of Catapult Sports

Courtesy of Catapult SportsThe top of a Catapult report from Australian Rules Football. Click here for a bigger image.

Maximum fitness is the product of interlinked systems: the neurological and the physiological, the metabolic, musculoskeletal and nervous systems. So Catapult is gathering everything, from simple measurements like heart rate to more intricate ones like acceleration, direction of movement, stops and starts, and the associated force -- more than 100 data points per second. It's more than most teams can put to use -- for now -- and one of the key tricks is figuring out what, out of all that, matters most.

There are hurdles to this kind of monitoring coming to regular season NBA games. For instance, the players and their agents may have good reason to resist. Although McCoy stresses the data should always be applied to compare a player to himself, it’s not hard to envision teams wielding their findings during contract negotiations or when reducing a player’s minutes when it confirms the perception that he’s dogging it on the court. “It’s CARFAX for the athlete,” he said. A consequence of this system being fully implemented would be teams simply knowing a lot more when it comes to signing players or trading them to other teams.

So the Spurs have more than just their usual Spurs-ian reasons for keeping quiet on this. While four NBA teams are Catapult Sports clients (the Rockets, Knicks and Mavericks being the others), the monitors have generally been used only in practices and scrimmages. The Spurs’ use of the monitors at the Las Vegas Summer League is perhaps the closest the devices have come to actual league competition so far.

This kind of technology -- especially when it’s not well understood -- can be scary, even threatening to the established order of things. It can also dehumanize athletes, on a spreadsheet, a human appears to be an asset to be monitored and controlled from afar. A certain amount of skepticism, a concern for best practices, is well-founded.

But the information, new perspectives and, eventually, results this kind of monitoring can produce can break down resistance. The edge teams constantly look for doesn't always come from the most likely sources. Biometric monitoring isn’t a cure-all, but it’s a logical next step, particularly when it comes to the most human of pursuits: keeping people healthy and functioning at their best. As McCoy said, “What we can measure, we can manage. If you can’t or aren’t measuring it, you can’t manage it. It seems really, really simple.”

Gatsby believed in the green light even though it was something he could never reach, maybe because it was something he could never reach. But that green light on Baynes’ back signals something different: that we can stretch out our arms farther and grasp a better understanding. That tomorrow, we will run faster.