Since entering the NBA in October 2003, LeBron James has transformed from one of the league's least effective volume scorers into a hyper-efficient offensive mastermind, dominating opposing defenses with an incredible blend of interior scoring prowess and perimeter shot creation.

On Thursday he launches the next chapter of his career, and while there's little doubt that James the scorer will continue to thrive in Los Angeles, there are legitimate reasons to question whether the new-look Lakers include enough firepower to take advantage of James' unique ability to create great looks for his teammates.

Let's go inside his journey to offensive greatness and what it means for this new test in L.A.. We'll start at the very beginning.

How LeBron owned the paint

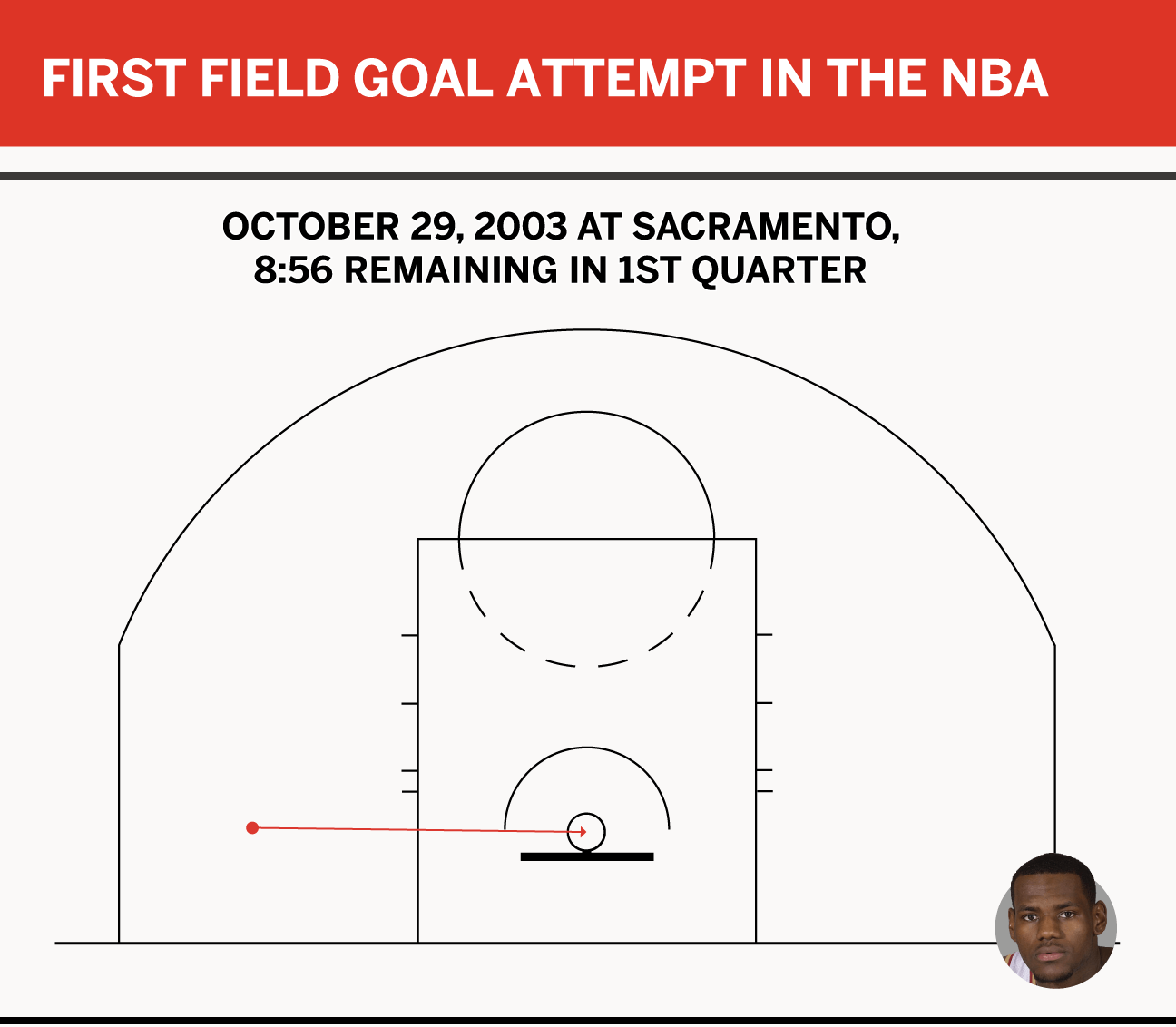

Just two days after Lonzo Ball turned 6 years old, James made his NBA debut in Sacramento. It didn't take him long to get going. After coming off a screen set by Carlos Boozer about three minutes into the game, James dribbled into his first NBA shot attempt. It was a foreboding success for the kid from Akron; the jumper found the bottom of the net:

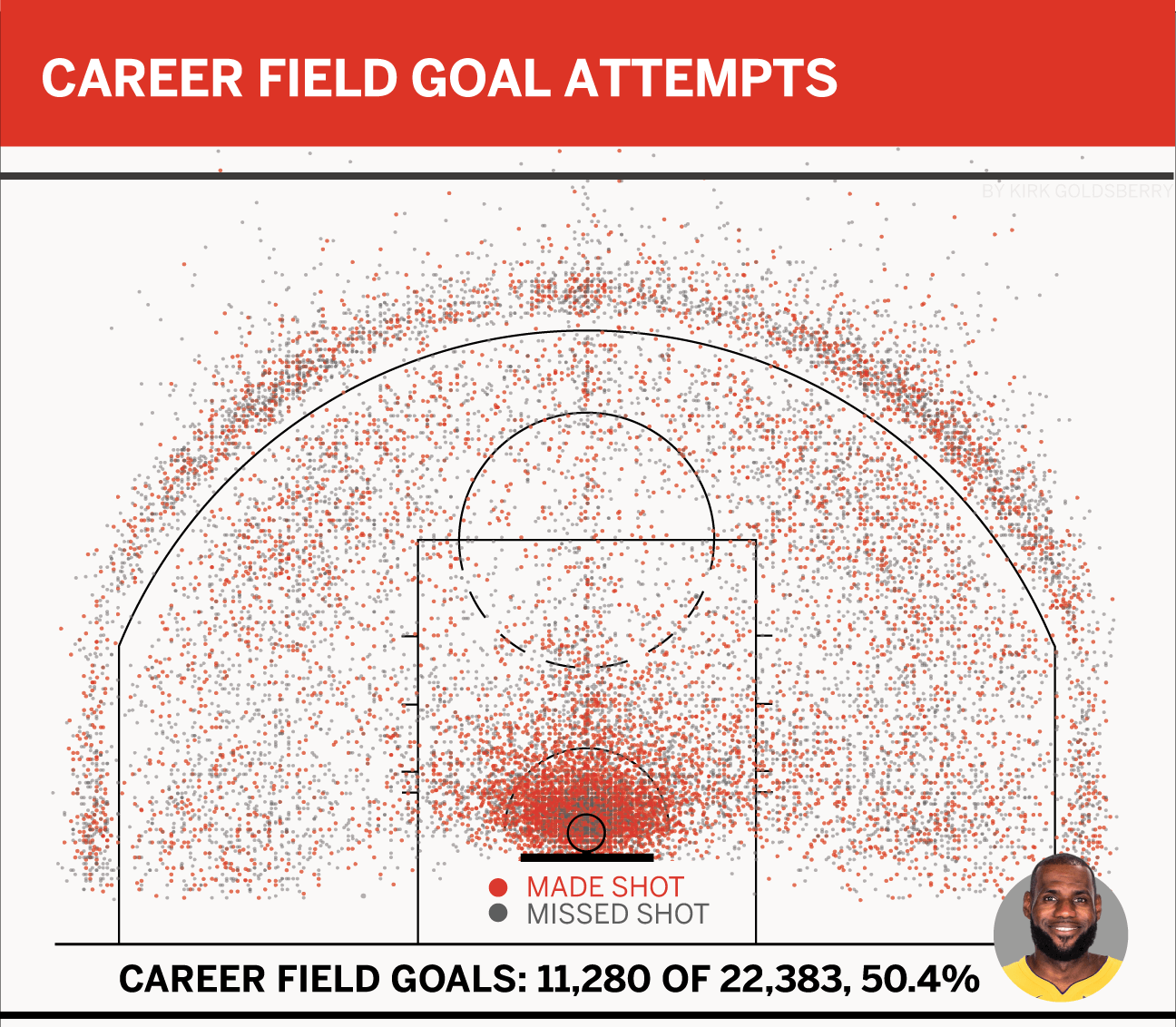

Since that first bucket, James has attempted an additional 22,382 regular-season field goals and made 11,279 of them. He'll begin the season Thursday night as the seventh-leading scorer in NBA history. If he stays healthy, it's reasonable to expect him to jump ahead of Dirk Nowitzki, Wilt Chamberlain and Michael Jordan into fourth place by the end of the regular season.

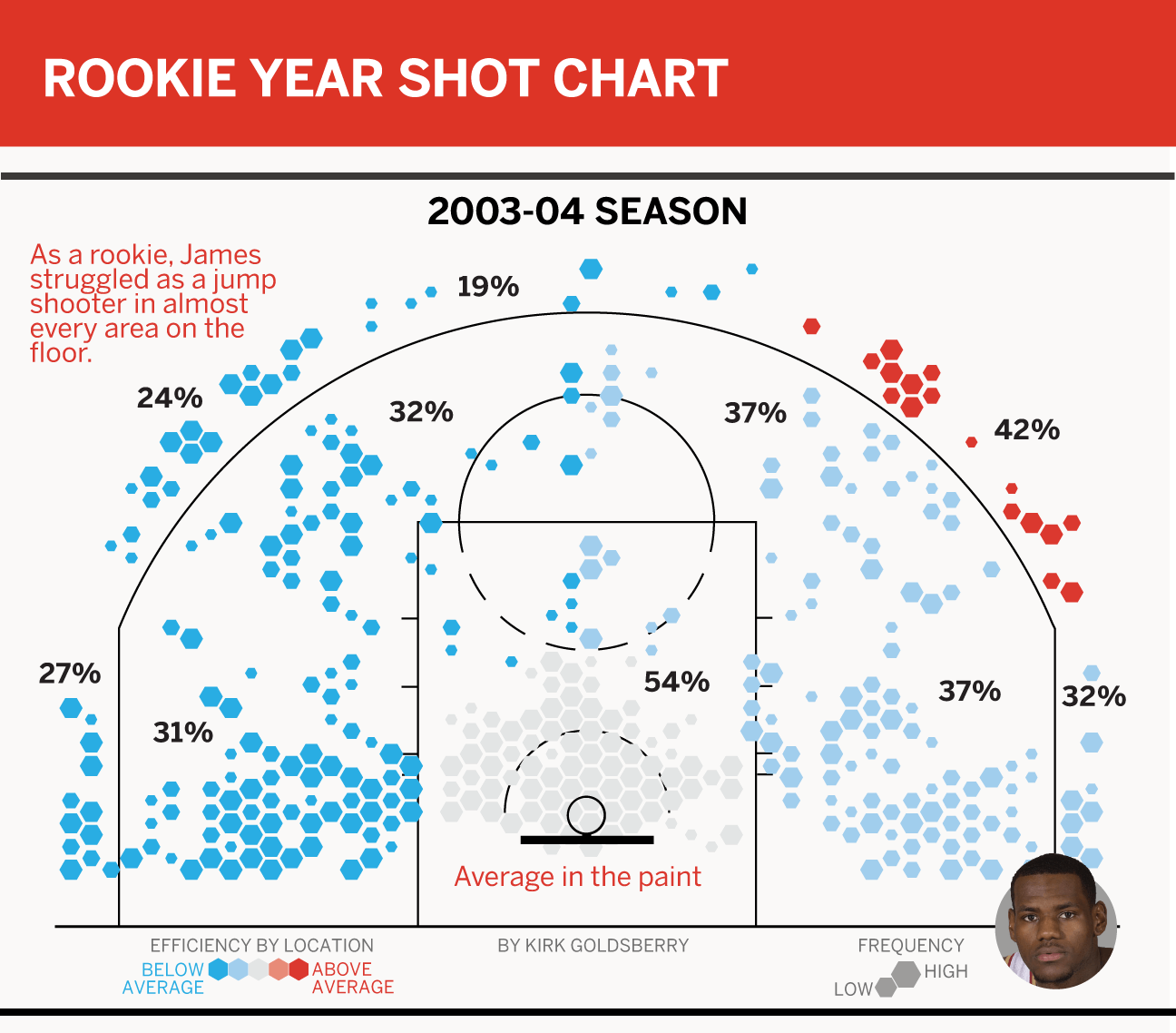

But James struggled mightily as a scorer in his rookie campaign. Of the 46 players who attempted at least 1,000 field goals that season, James ranked 41st in effective field goal percentage. His rookie shot chart reveals a young player who was a mediocre jump shooter and merely average in the paint. He hadn't yet figured out how to use his size and speed to get easy buckets at the rim or draw trips to the line, and to say his jumper was inefficient is a major understatement.

He was no king yet. Consider this trio of plebeian stats:

Out of 74 NBA players who attempted at least 200 3-pointers that season, James ranked 72nd by converting just 29 percent of his attempts. Only Jason Richardson and Antoine Walker were less efficient from downtown.

Out of 126 NBA players who attempted at least 200 midrange shots, James ranked 119th.

Out of 114 NBA players who attempted at least 200 shots in the restricted area, James ranked 72nd.

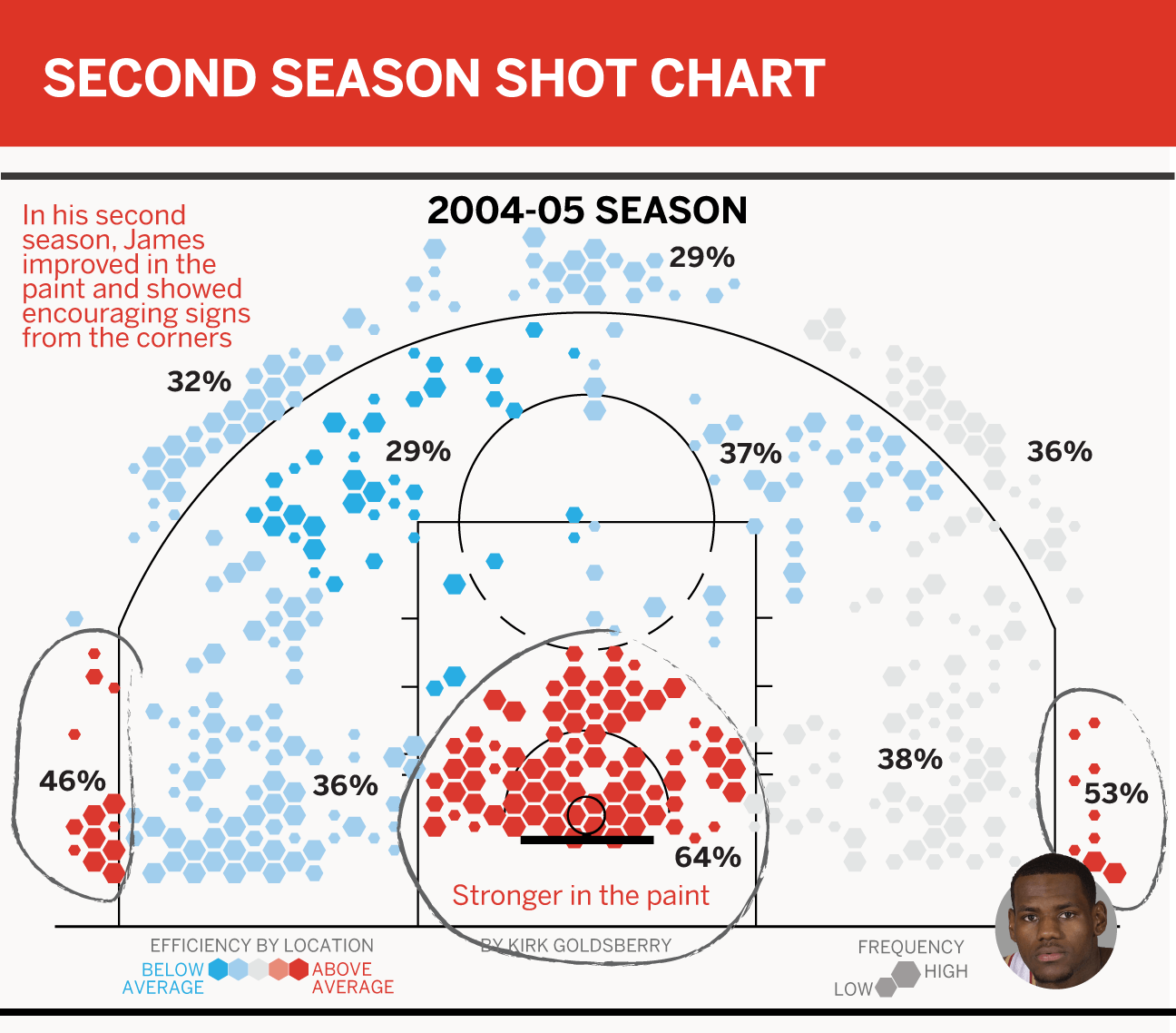

To date, his rookie year stats include career lows in field goal percentage, true shooting percentage, free throw rate, PER and assist percentage. But, in his second season, James improved in almost every key statistical category.

He showed flashes of the interior monster he would soon become by finishing stronger at the rim, drawing more fouls and forcing fewer shots. His 3-point percentage went from terrible to average, though despite some promising numbers in the corners, he remained a relatively modest perimeter threat:

James' ability to score at the basket would quickly become his calling card. In his first playoff series in 2006 against the Wizards, James converted two huge late-game buckets to propel his team to victory. He won Game 3 with a dribble drive punctuated by a brutal ball fake that sent Antonio Daniels flailing out of the play, followed by an impossible hanging layup over Michael Ruffin. He won Game 5 with a lightning-fast baseline drive that required equal parts speed, power and touch as his layup winner put it away with 0.9 seconds left in overtime.

The key to unlocking his potential as a young scorer was simple: find ways to play to his strength, which was finishing at the bucket. The story of James transforming from inefficient rookie into NBA scoring champion is one of a player learning how to attack defenses with his ferocious blend of speed and strength to create scoring chances in the paint. That's still the key to his scoring portfolio now.

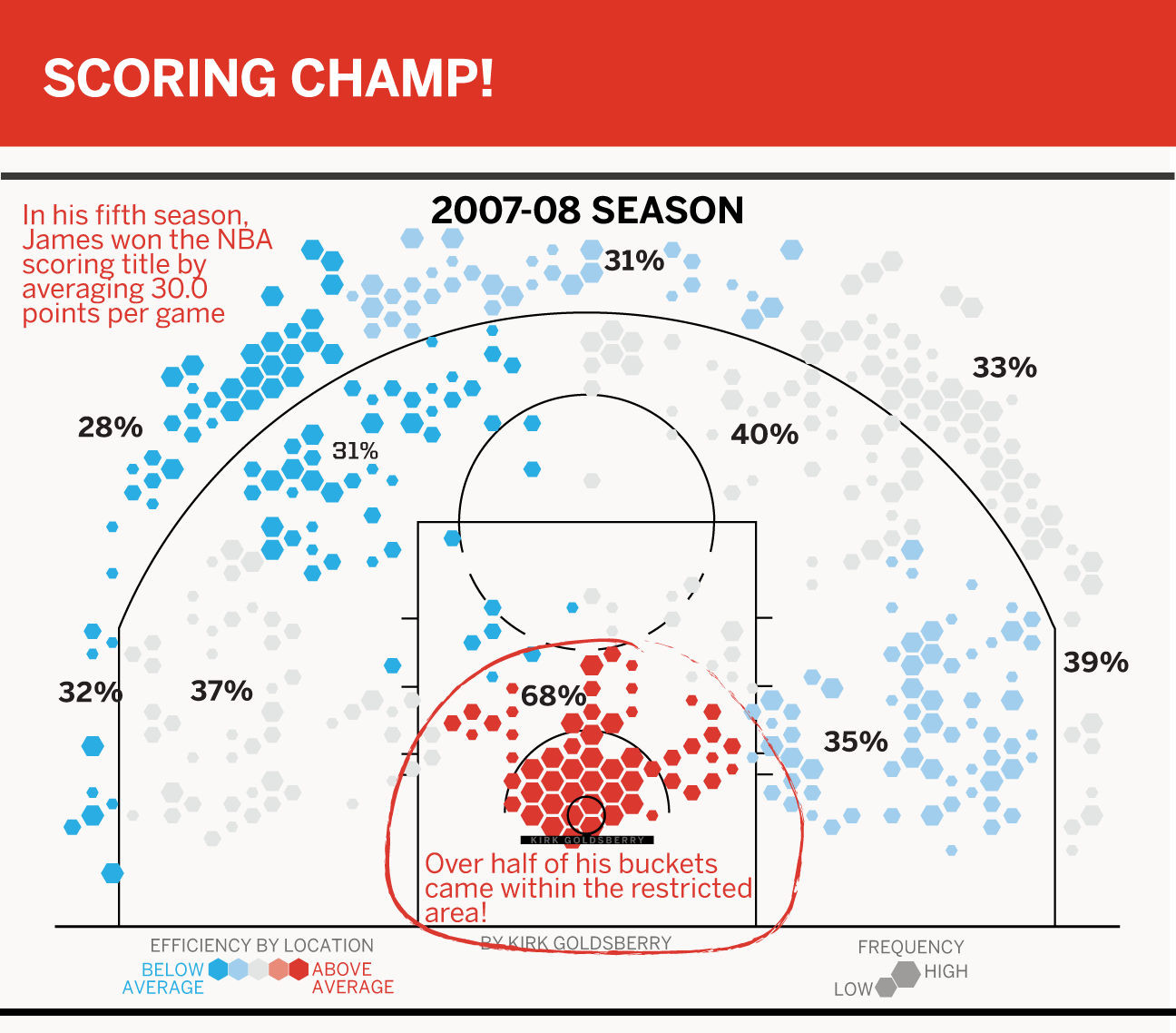

During the 2007-08 season, James was the only player to attempt 600 or more shots in the restricted area. On his way to the scoring title, he led the NBA by converting 794 field goals, but incredibly 440 of them (55.4 percent) came within the restricted area. James became the best in the world at scoring in the little area that NBA defenses work to protect the most. Who needs a great jump shot when you can score that much in the paint?

By 2008 James had realized his potential as an individual player. He was truly the most versatile star in basketball. In the 2008-09 season, he led his team in points, rebounds, assists, steals and blocks. That's incredible. But it also suggests he wasn't exactly surrounded by a great supporting cast. As James entered his prime, he migrated from Cleveland to Miami. He surrounded himself with a much better basketball environment, and what came next was arguably peak LeBron James. Playing alongside Chris Bosh and Dwyane Wade, James could pass up the difficult shots that came from operating next to an uneven supporting cast.

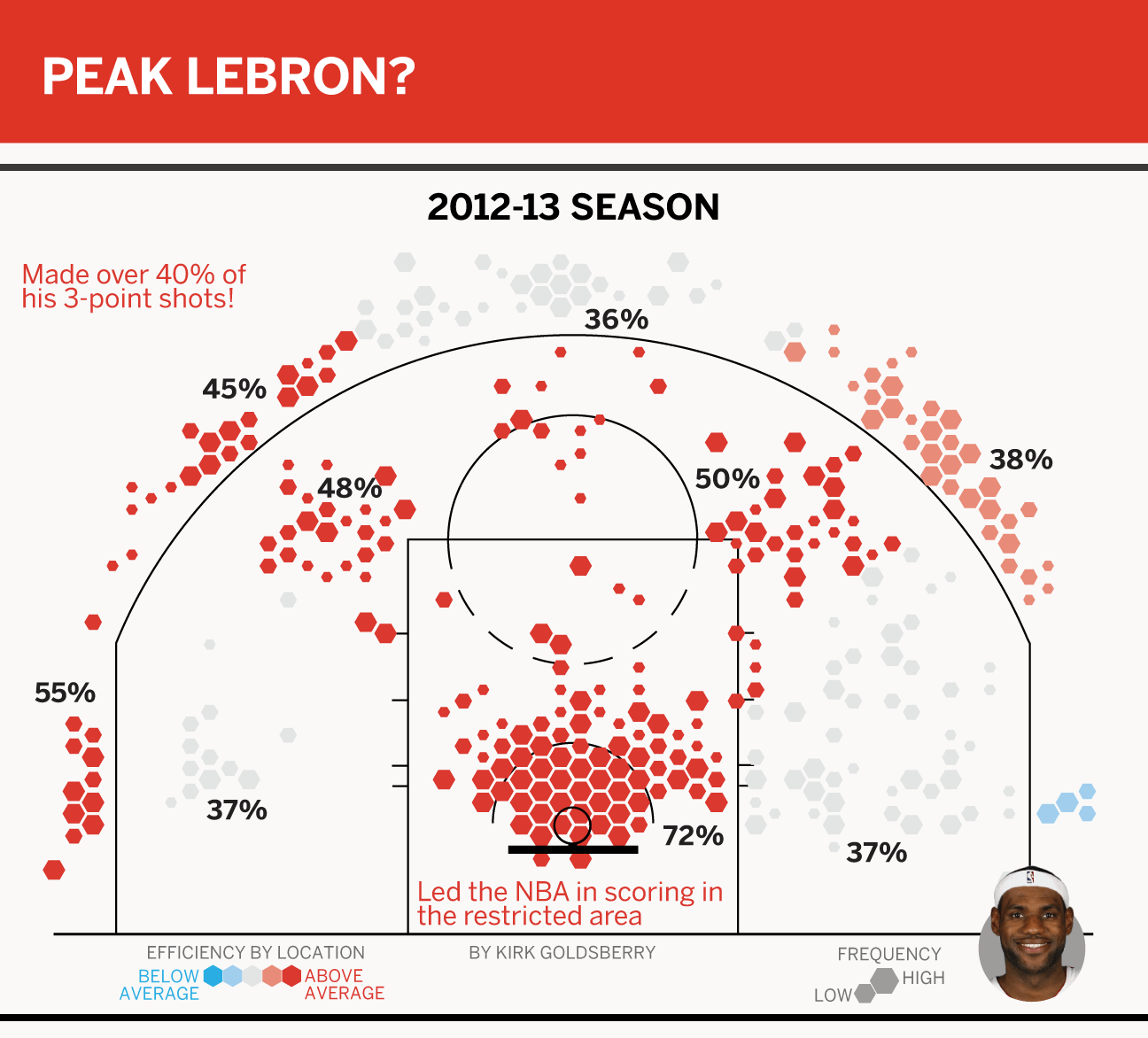

In his final two Miami seasons, he took the fewest attempts per game of his career. He became obsessed with efficiency, especially in 2012-13, the second championship year. Look at all this curated red. Essentially, it's a masterpiece:

James was liberated from being the entire focus of the offense. He learned to play off the ball. He learned to be more selective and more intentional with his shot selection. It was a luxury that comes with playing on a great team. Sometimes efficiency has as much to do with a player's surroundings as his individual abilities.

As his numbers soared to new heights, those who studied James the most honed in on the confluence of lower usage, higher efficiency and hyper-intelligent shot selection. Just check out what ESPN's Brian Windhorst wrote in May 2013, after James won his fourth MVP award:

"Less bad shots, more good shots, more attempts from places he learned he was good at shooting from against defensive strategies, less attempts against strategies that were designed to bait him into bad decisions. ... It was often dismissed as a hot streak or the result of a bunch of dunks. It was so much deeper than that. It was James applying his understanding of a decade in the NBA and merging it with his talent."

Peak LeBron manifested when his brain, his body and his playing situation all aligned in Miami. After years of being a poor or average 3-point shooter, it was there that James finally put up strong numbers from deep. That improvement says as much about how clean his attempts were as it does about how good he is at shooting 3s. In 2012-13, 55 percent of his triples were assisted. Last year in Cleveland, only 36 percent were.

And while he'll never come close to matching Stephen Curry from deep, it might not matter much. James' interior stats remain as staggering as Curry's perimeter prowess.

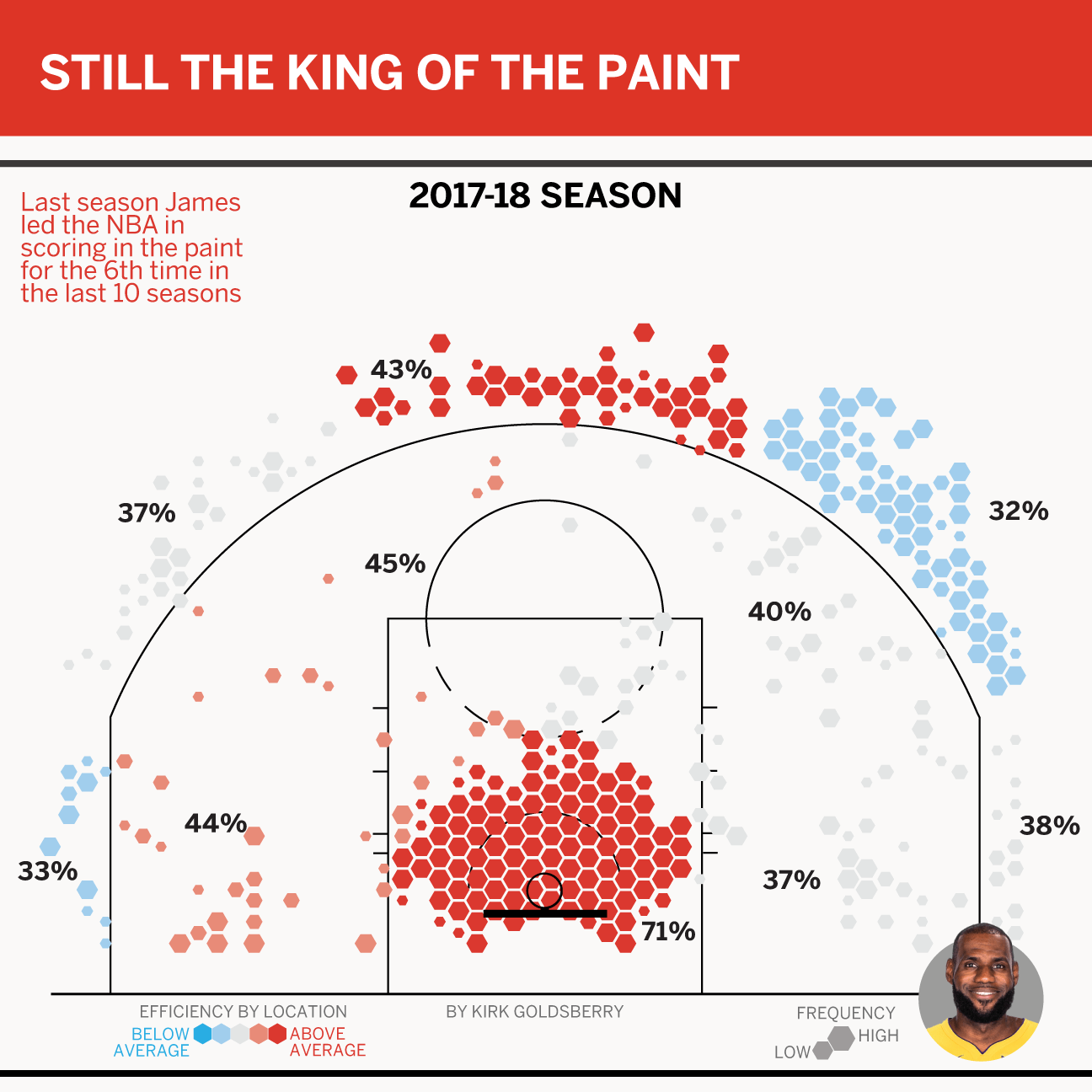

Consider this: In the 10-season span from 2008-09 through 2017-18, James has been the NBA's leading scorer in the restricted area an incredible six times, including last season when he converted an astonishing 534 field goals in that critical zone. Not only was that the biggest number of LeBron's career, but no player had scored so many buckets there since MVP-level Shaq put up 571 in 1999-00. Back then, everyone knew Shaq was the most dominant interior scorer on the planet. But for the past 10 years that title has belonged to James:

This doesn't mean James can't generate much perimeter offense. In fact, it's one of his best skills.

A different kind of 3-point specialist

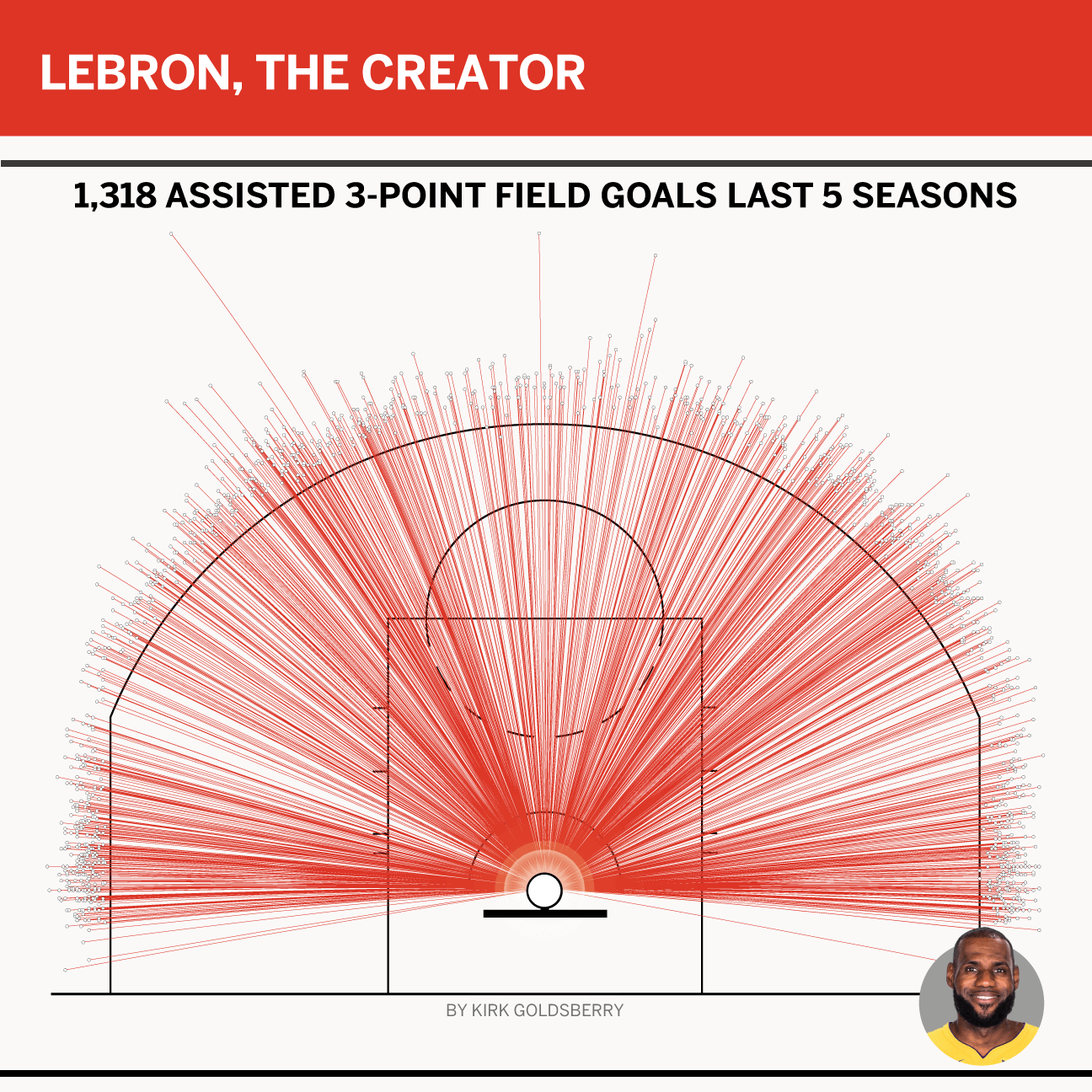

One way James has overcome his relative mediocrity as a jump-shooter is his ability as a creator. He is arguably the best 3-point assister in the NBA.

Last season, James Harden led the NBA by sinking 265 3-pointers. That's a big number -- it helped Harden win his first MVP -- but James led the NBA by assisting on 344 3-pointers. Over the past five seasons, Curry has emerged as a new kind of scoring wunderkind, draining an incredible 1,485 3-pointers since 2013-14 season. But in that same period, James the creator has assisted on 1,318 made triples.

Everyone knows that James is a terrific passer. Few players draw as much attention as he does. So as defenses have attempted to slow down his dribble drives with helpers, James has learned to punish these strategies by firing perfectly timed passes to the shooters those defenders have left open.

To defend James over the past decade is to pick a poison: Either you let him blow by one-on-one coverages and score countless buckets at the rim, or you slow down his interior attacks with help defense and allow him to create clean looks for his teammates. Both the Cavs and the Heat did well to surround James with spot-up threats who could make defenses pay for leaving dudes open on the edges. You don't abandon Kyle Korver or Ray Allen in the corner. That opened up driving corridors for James to score at the rim.

As James enters his 16th year in the NBA, it's fair to ask whether this new batch of teammates will enable him to extend his legacies as either the league's best interior scorer or the league's best 3-point assister.

Last season in Cleveland, well over half of his 3-point assists were distributed among three very good shooters: the five-time All-Star Kevin Love, the supremely talented JR Smith and the phenomenally accurate Korver. They're stuck in Cleveland, and it's unclear whether this roster assembled in L.A. has enough perimeter firepower to take advantage of James' unique creative abilities. In turn, defenses might be able to devote more resources to helping slow James the driver.

Here's one important question as we head into the 2018-19 season: What's going to happen when these kinds of passes fall into the hands of his new teammates?

A dose of pessimism is warranted. It's not encouraging that during the preseason, the Lakers' most active 3-point shooters -- Kyle Kuzma, Josh Hart, Kentavious Caldwell-Pope and Svi Mykhailiuk -- combined to make only 28 percent of their 81 3-point tries, while the team as a whole made just 32.6 percent. Still, preseason samples are both small and sketchy, chemistry takes time and if we've learned anything about James since 2003-04 it's that he is the rising tide lifting all boats.

The question isn't whether the Lakers will get better. They obviously will. The question is how much better will they get. Last season, they had the 23rd-most efficient offense in the NBA in part because they were one of the worst long-range shooting outfits. That has to change, and perhaps there's no better way to improve that number than by handing the keys to the offense over to the king of clean looks.

Ultimately, the degree of improvement depends largely on the abilities of a bunch of unproven snipers to hit long-range shots. If KCP, Kuzma and Hart can drain their 3s, this wacky experiment might actually work. If they can't, Rob Pelinka, Magic and GM LeBron will have to figure out ways to supply James with perimeter threats who can.