Head | Knee | Foot/Ankle | Shoulder | Elbow | Hand

Note: This is an overview of injuries commonly seen in sports and shouldn't be used as a means of diagnosis. If an injury is suspected, please seek medical advice.

Head

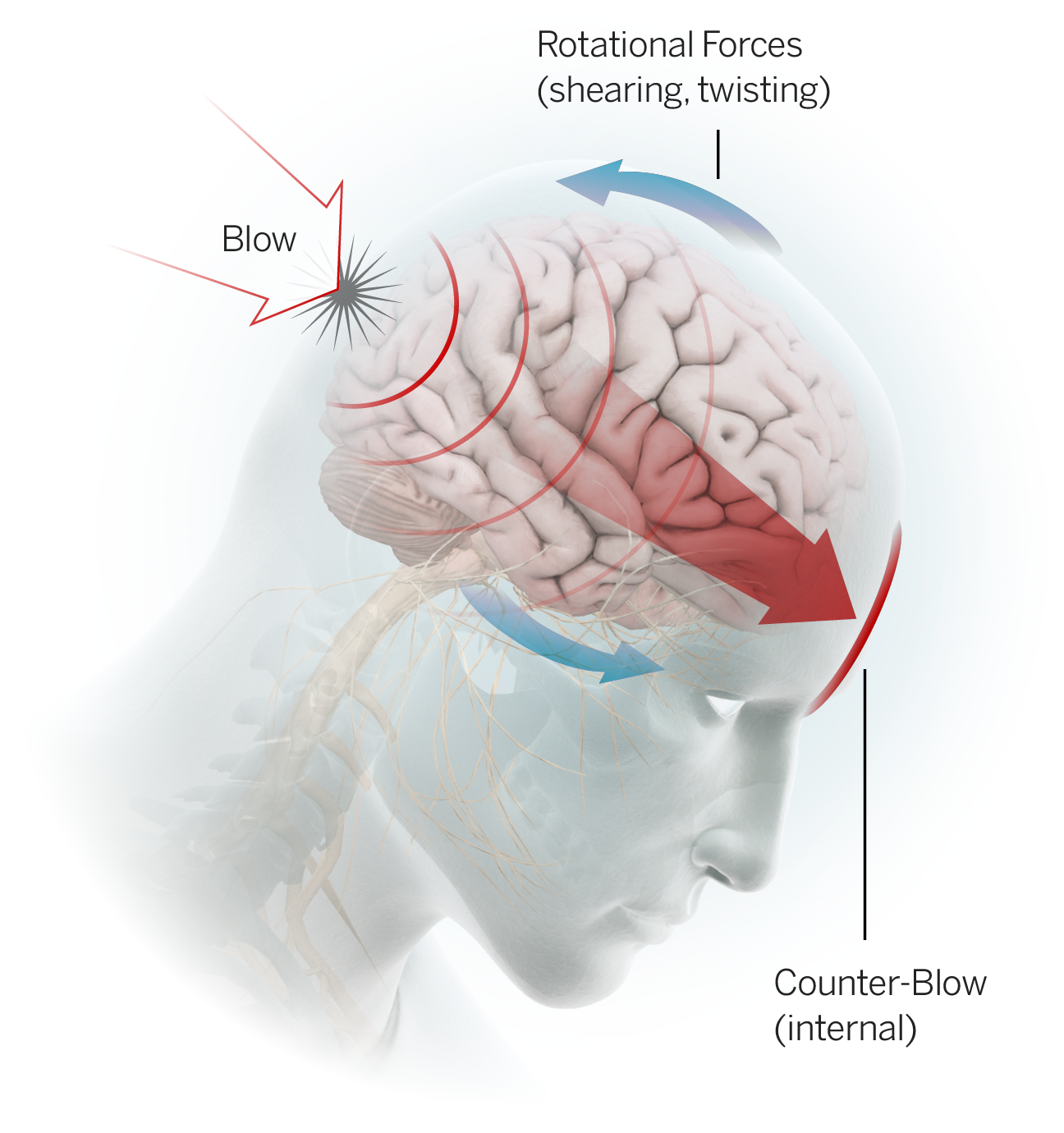

Concussion: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) classifies concussion as a form of traumatic brain injury (TBI) caused by a "bump, blow or jolt to the head." Concussion may also be caused by a fall or bodily impact that results in vigorous back-and-forth motion of the head and brain. While concussions are not typically life-threatening and the majority will resolve within days, they can present with a wide range of signs and symptoms of varying intensity and duration. Symptoms the athlete may complain of include but are not limited to: headache, nausea, dizziness, fogginess, sensitivity to light, irritability and difficulty concentrating. Signs which may be observed in an athlete who is believed to have suffered a concussion may include but are not limited to: loss of consciousness, disorientation/confusion and vomiting.

An athlete exhibiting any features of concussion should be immediately removed from play and further evaluated by medical personnel. Any player diagnosed with a concussion should not return to play on the day of injury. It is also important to note that symptoms of a concussion can emerge hours after the injury occurs. Return to play criteria for any sport typically includes the following: The athlete must be completely symptom free both at rest and during physical activity; results of neurocognitive testing (which measures how the brain processes information) must return to baseline levels; the athlete must have progressed through a graded exercise protocol without recurrence of symptoms; and the athlete must have received clearance to return to play from a medical provider with expertise in concussion management.

There have been several key developments in the area of concussion management in professional sports in recent years including guidelines related to removal from and return to play, in-game rule changes and roster management tools. Scientific research is ongoing to improve concussion diagnosis and management, but there is still much more to learn. Concussion remains one of the most complex injuries in sport.

Knee

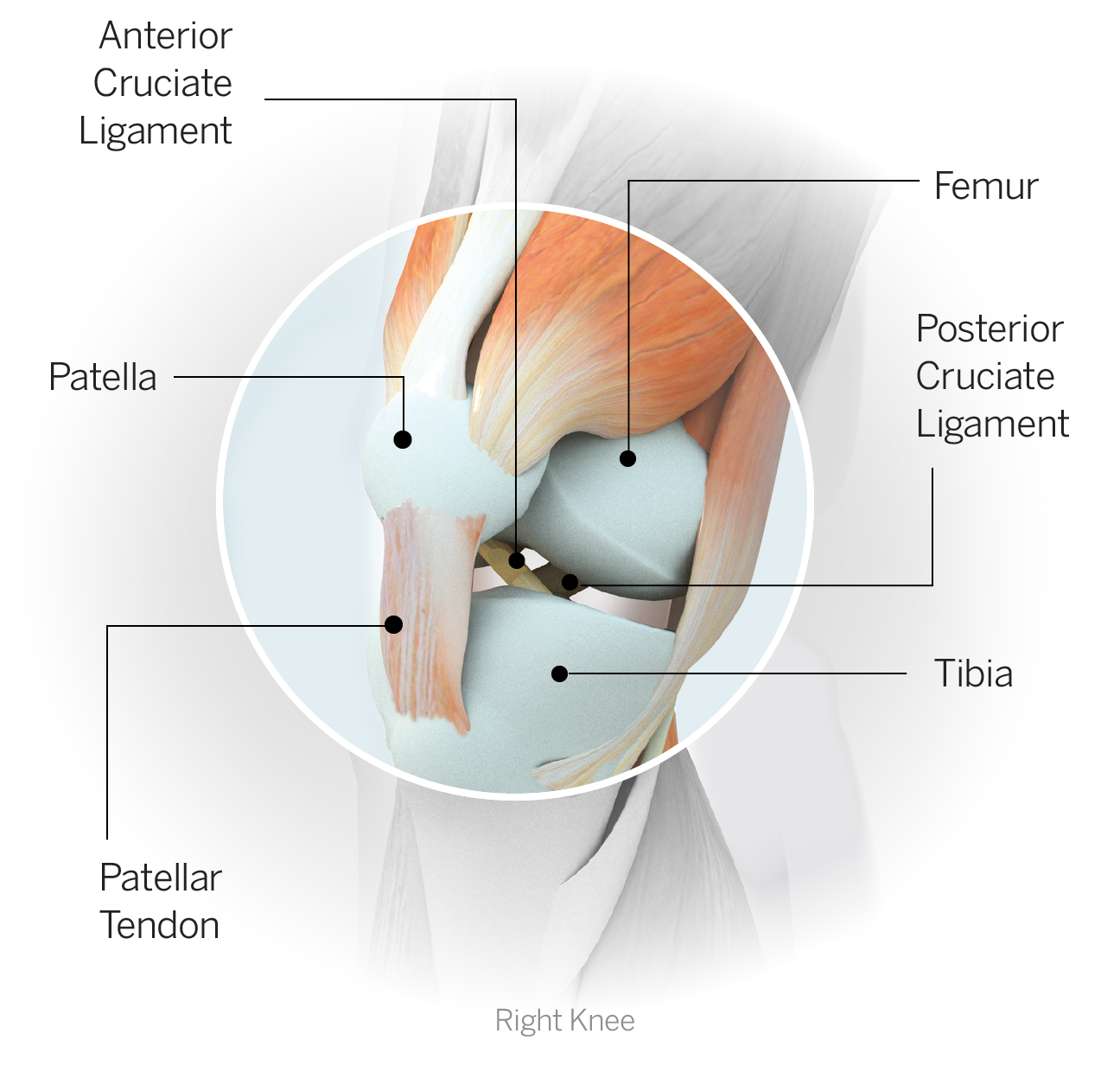

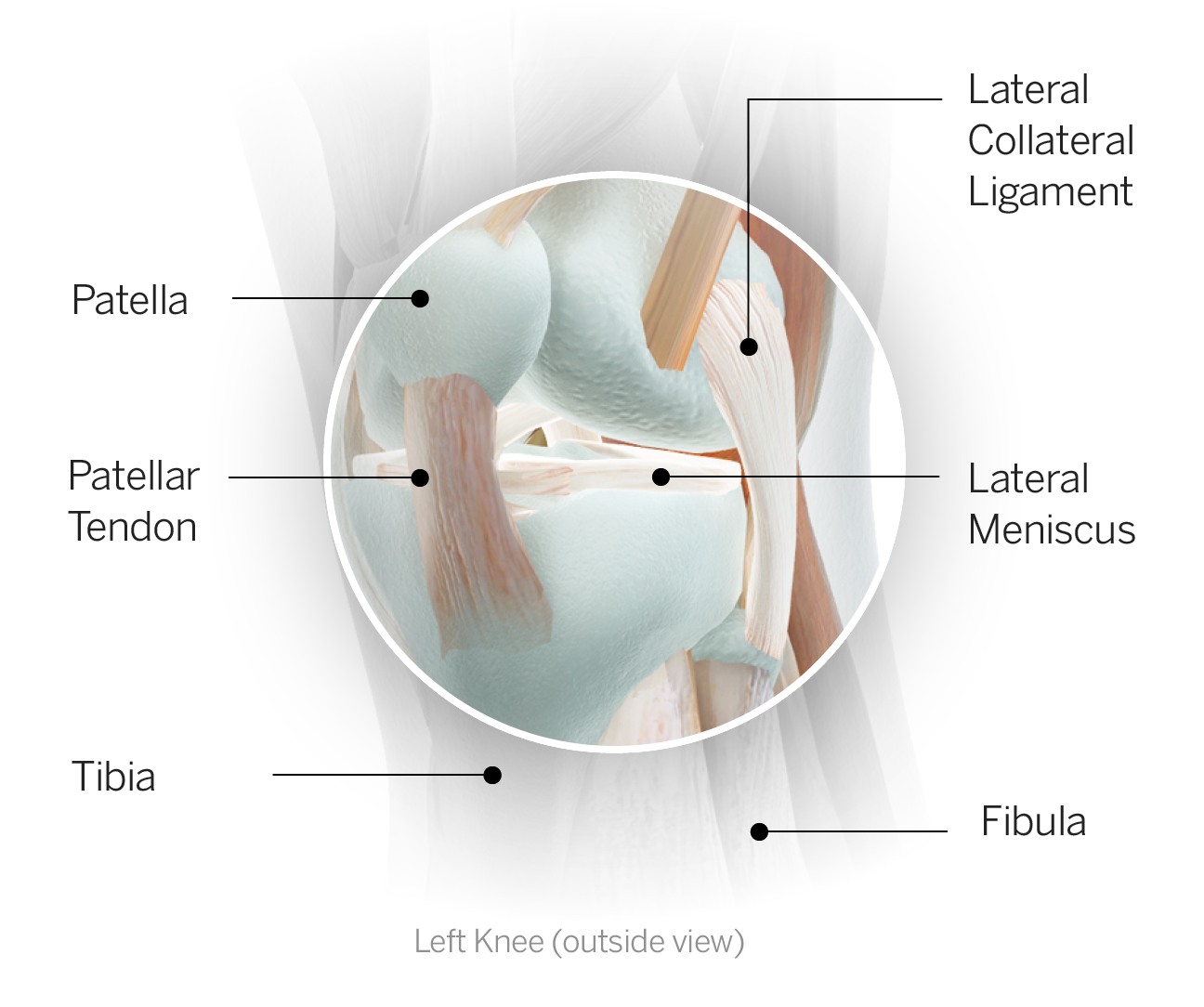

Tibia: One of the two lower leg bones, more commonly referred to as the shin. The relatively flat top portion forms part of the knee joint, and the bottom forms the roof of the ankle.

Fibula: One of the two lower leg bones; the fibula is the long, skinny outer bone whose inferior tip forms the lateral (outer) aspect of the ankle joint.

Patella: The kneecap. It is a teardrop-shaped bone that rests lightly in a groove on the front of the femur and is embedded within the tendon that anchors the quadriceps muscle. As the knee is alternately flexed (bent) and extended (straightened) the patella glides up and down in the groove. The patella can dislocate during an awkward bend of the knee; typically if the knee collapses inward, the patella, via a forceful contraction of the quadriceps, dislocates laterally (to the outside). It can also fracture if subjected to high forces, particularly during impact.

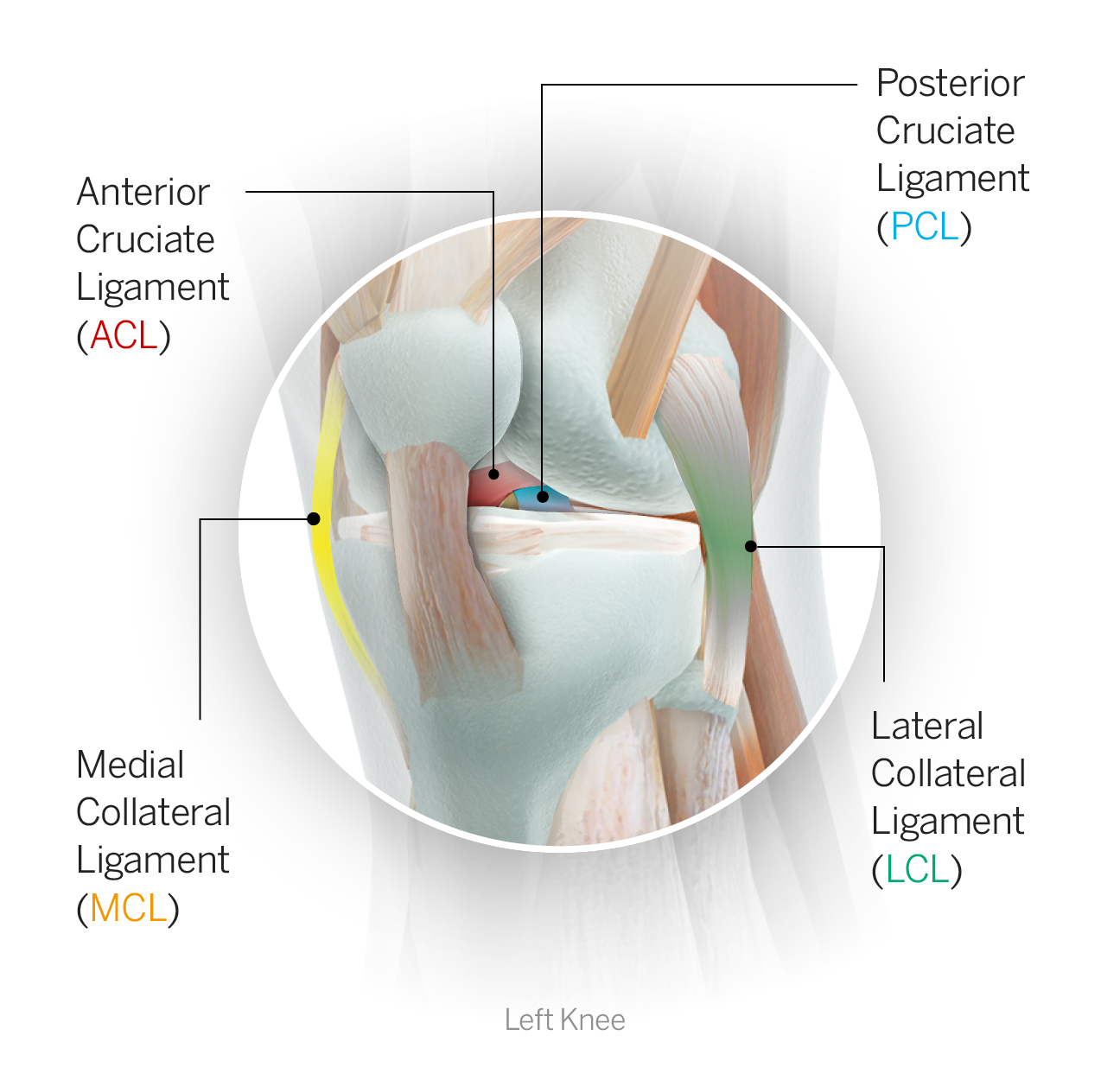

ACL: The anterior cruciate ligament is one of the four primary stabilizing ligaments of the knee. It sits deep inside the joint, coursing diagonally from the tibia to the femur and crossing in front of the PCL, and helps control anterior shear forces of the tibia relative to the femur. ACL tears have become one of the more recognizable injuries in sports and are often noncontact in nature, occurring during a combined deceleration-rotation movement. ACLs also can be torn during a contact injury involving a blow to the knee, particularly if the foot is planted. Depending on the nature of the injury, the ACL can either be torn in isolation or accompanied by damage to other structures within the knee. ACL tears are typically season-ending injuries that require surgical repair and a subsequent rehab averaging approximately nine to 12 months.

PCL: The posterior cruciate ligament is one of the four primary stabilizing ligaments of the knee. It sits deep inside the joint and crosses behind the ACL. It helps control posterior shear of the tibia relative to the femur.

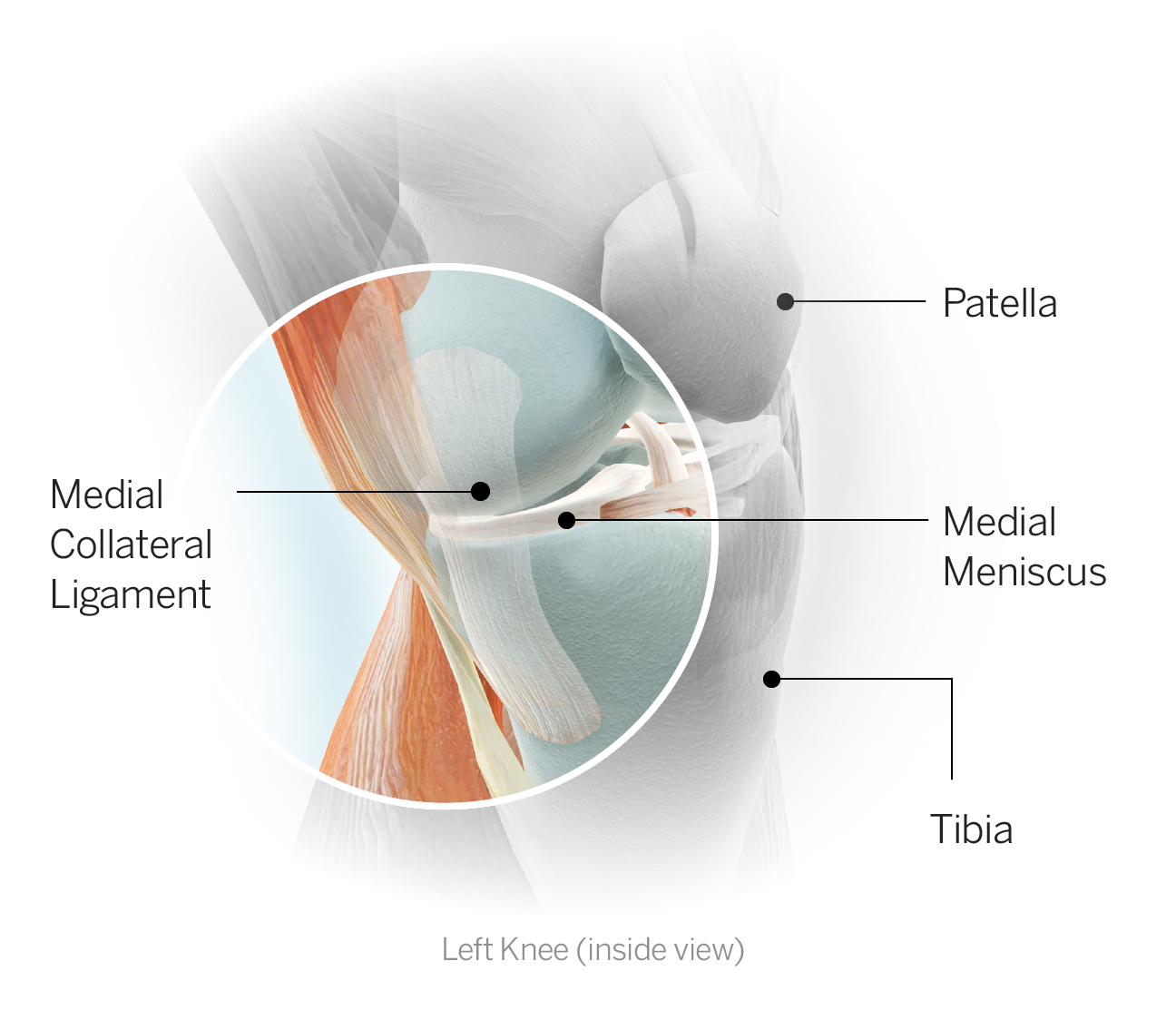

MCL: The medial collateral ligament is one of the four primary stabilizing ligaments of the knee. It reinforces the medial (inner) side of the joint and runs from the femur (thigh bone) to the tibia (shin bone). The MCL is often injured by a hit to the outer knee that forces the knee inward. An injury here can make it difficult for an athlete to move in a side-to-side direction.

LCL: The lateral collateral ligament is one of the four primary stabilizing ligaments of the knee. It reinforces the lateral (outer) side of the joint and runs from the femur to the fibula. An injury here can be caused by a blow to the inner aspect of the knee, directing a force outward and damaging the LCL. It can also be involved in a multiligament injury typically resulting from a posteriolaterally directed force.

Meniscus: A fibrocartilage disc of which there are two (menisci) in each knee, medial and lateral. The menisci are positioned on top of the tibia and provide cushioning within the joint in addition to enhancing overall stability. The meniscus is subject to tearing, particularly when the knee experiences twisting. It can also develop small tears or fraying over time. Due to its poor blood supply, the meniscus does not heal on its own. Surgery is required to address a meniscal tear and can take the form of resection (removing or shaving down the damaged portion of the meniscus) or repair (where the tissue is sutured in an effort to retain as much of the normal meniscus as possible with the goal of minimizing the risk of degenerative joint changes over time). There are many considerations involved in determining whether an athlete undergoes resection or repair, including the size and location of the injury and the viability for healing after repair, and the timetables to return to activity are quite different. A simple debridement (clean-up procedure to remove a small flap tear or smooth down rough edges) can allow the athlete, depending on individual healing, to return to sport within two to four weeks. In the case of a primary repair, the healing meniscus has to be protected in the early stages and a return to sport can take upwards of four to six months.

Patellar tendon: The patellar tendon is the broad, flat tendon that anchors the quadriceps muscle to the shinbone via its attachment on the front of the tibia, just below the knee. The tendon actually encases the patella and controls its position when the quadriceps contracts. The tendon is very strong, but when subject to high forces, especially in cases where there is pre-existing degenerative disease in the tendon, it can rupture, most often by pulling away from its attachment. Those cases are treated by surgical repair followed by an extensive rehabilitation process that can require six months or more of recovery.

Foot/Ankle

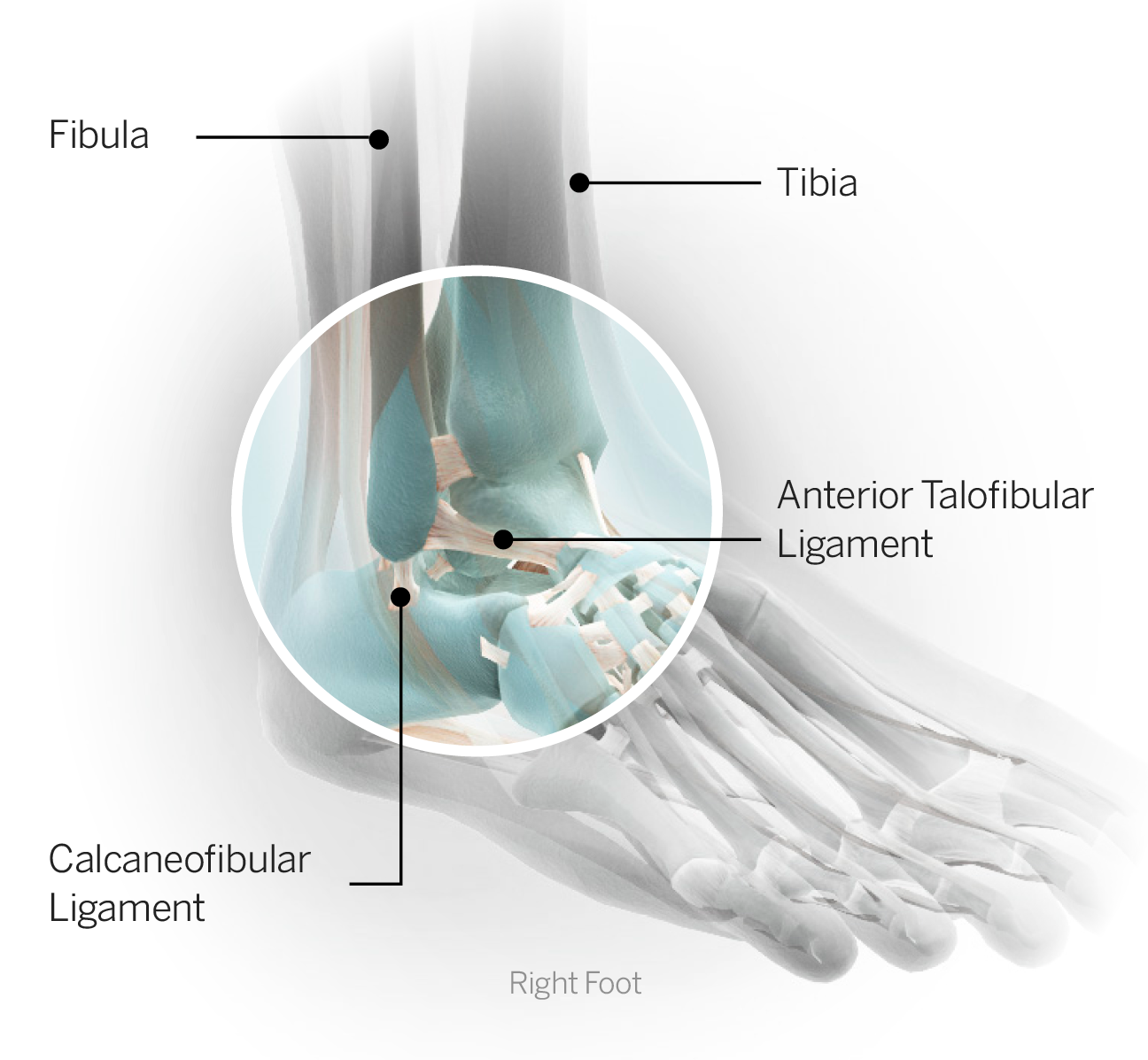

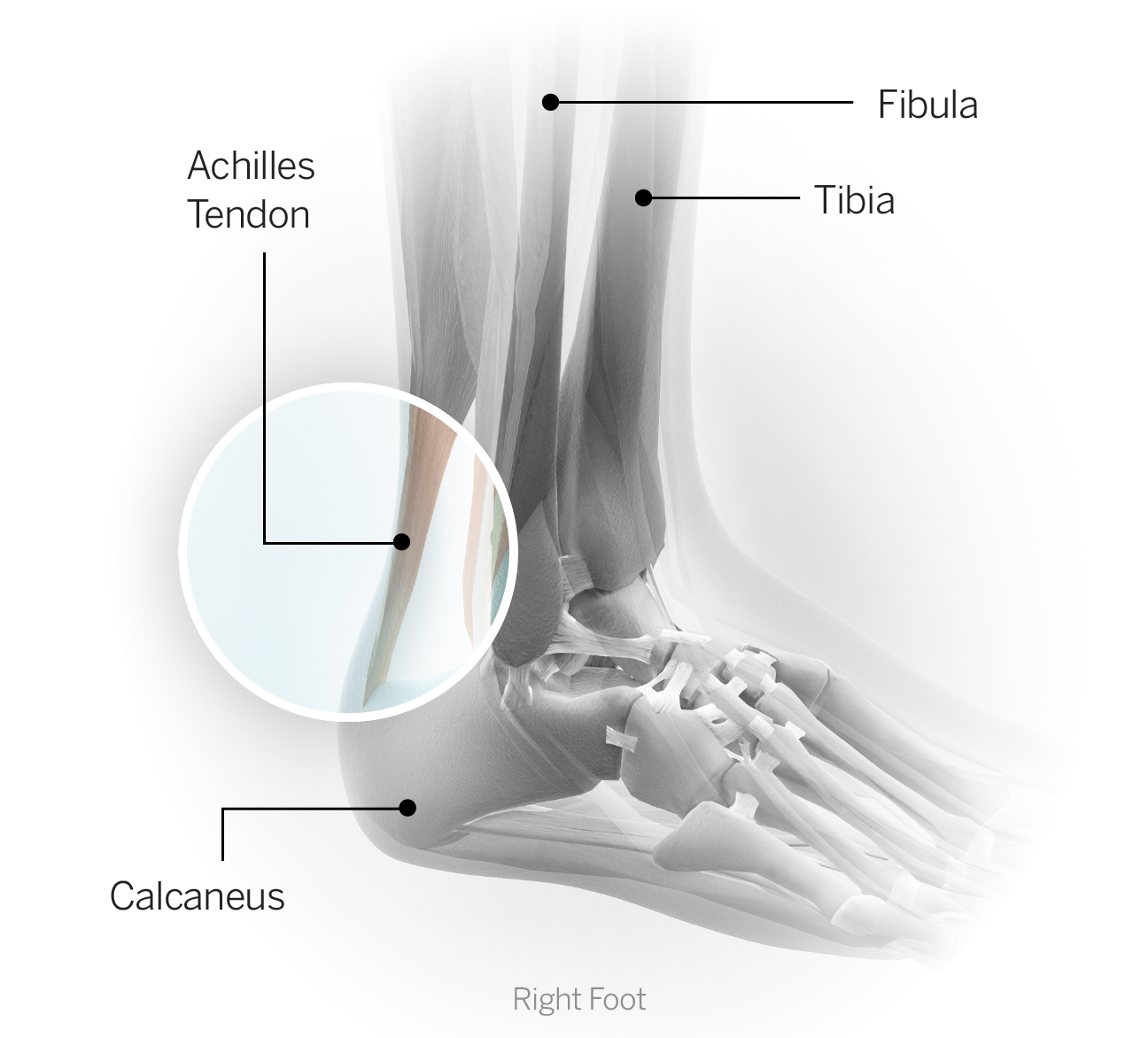

Tibia: One of the two lower leg bones, more commonly referred to as the shin. The relatively flat top portion forms part of the knee joint and the bottom forms the roof of the ankle.

Fibula: One of the two lower leg bones; the fibula is the long, skinny outer bone whose inferior tip forms the lateral (outer) aspect of the ankle joint.

Anterior talofibular ligament: On the outer ankle, this ligament runs from the talus to the fibula and helps protect against inversion (rolling of the ankle so the foot points inward), particularly when the foot is pointed slightly downward.

Tibiofibular ligaments: The tibiofibular (or tib-fib) ligaments connect the two lower leg bones -- the tibia and fibula -- at the superior portion of the ankle joint. An injury to these ligaments constitutes a high ankle sprain.

Ankle sprain (lateral): The most commonly injured ligament with a lateral ankle sprain is the anterior talofibular ligament. Sprains can range in severity pertaining to both functional limitations and recovery time. Time to return to sport following a lateral ankle sprain can range from days for the mildest variety to months for a severe sprain.

High ankle sprain: This is also referred to as a syndesmosis sprain. An injury to the tibiofibular ligaments results in an injury to the roof of the ankle joint, hence the term "high ankle." If the ligament injury is severe enough to result in a gapping or widening between the two leg bones, the injury is considered far more serious and surgery may be required.

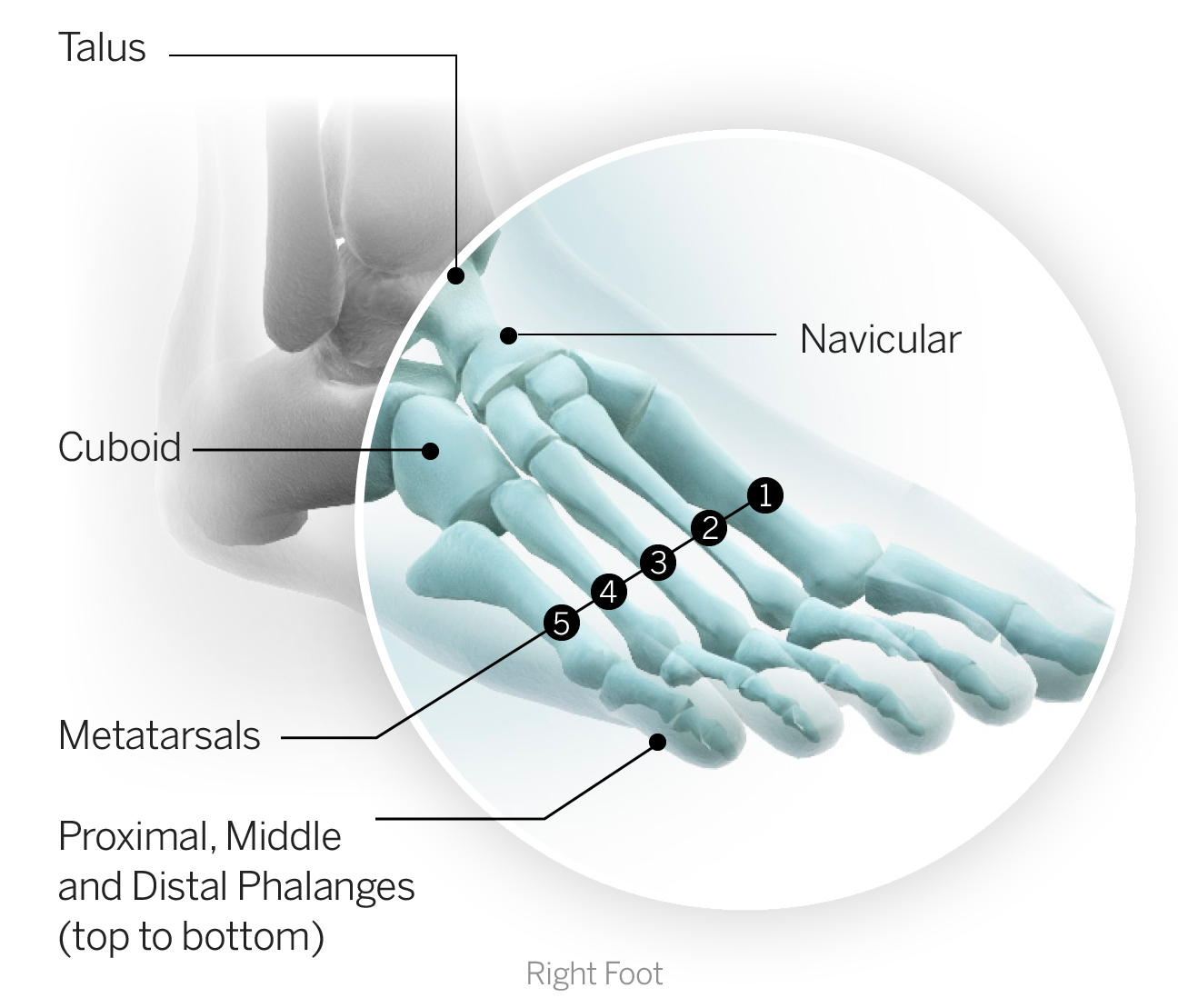

Talus: The bone that forms the main weight-bearing portion of the ankle joint where it interfaces with the tibia.

Metatarsals: The long bones of the forefoot, connecting the base of the toe to the midfoot. There are five, one articulating with each toe. Any metatarsal can sustain a fracture, but a fifth metatarsal fracture (on the outside of the foot) is the most common among athletes.

Fifth metatarsal fracture: Fifth metatarsal fractures represent a break in the long bone on the outer aspect of the forefoot that connects to the fifth (pinkie) toe. The area most often injured in athletes results in a break known as a Jones fracture. The fifth metatarsal is subject to significant torsional stress in an athlete during pivoting, pushing off, sharp deceleration and twisting. It also is subject to impact stress with repeated running and jumping. The bone does not have a particularly good blood supply, which results in a frequent failure to heal independently, even with immobilization. For this reason, surgical fixation of Jones fractures (with implantation of a screw) has become the standard of care, especially in elite athletes who will return to high-stress activities and whose specific movements in their sports put them at an otherwise increased risk of failure. Typical recovery requires eight to 12 weeks, although it is highly variable.

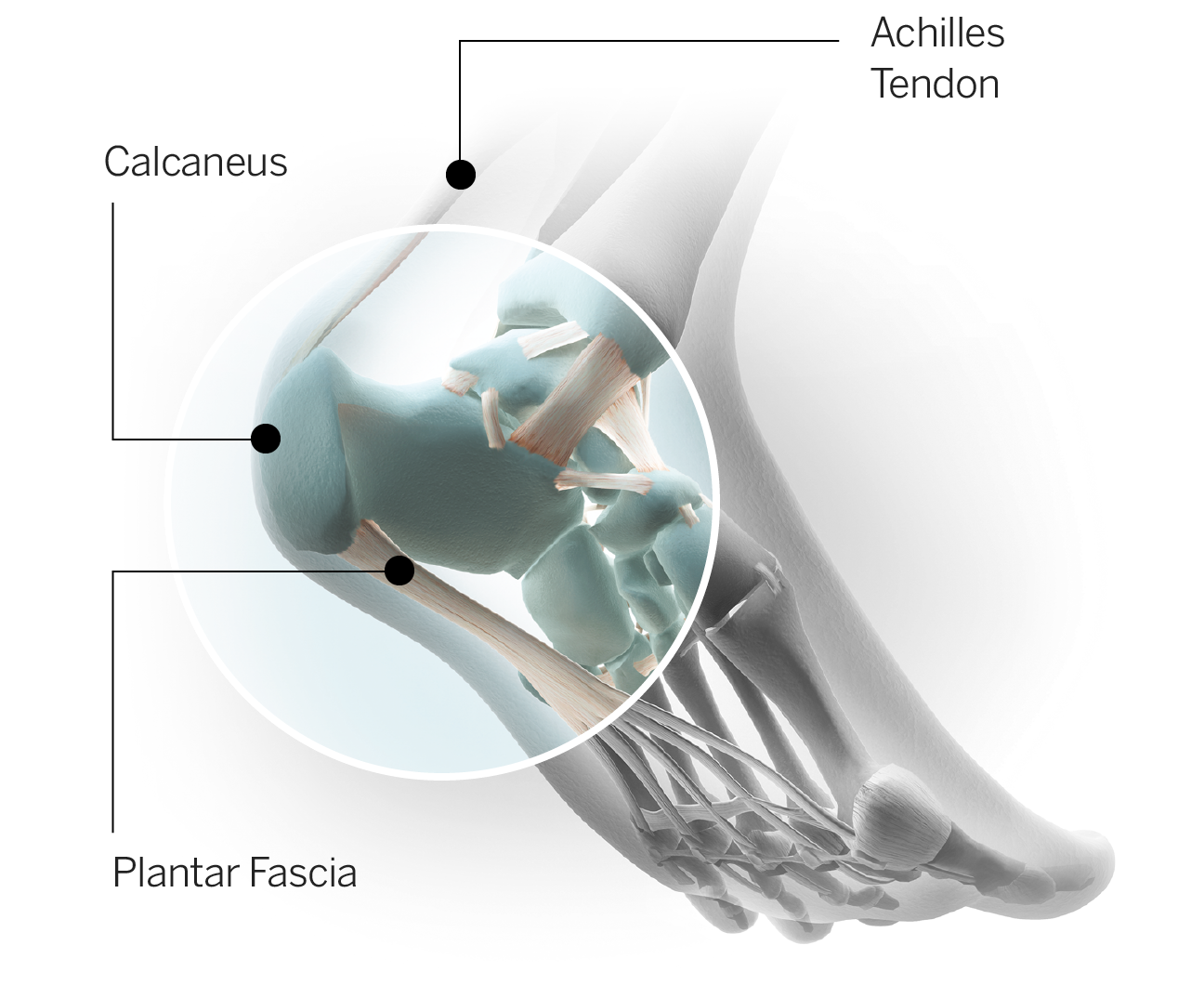

Plantar fascia: The fibrous tissue along the undersurface of the foot that runs from the heel to the ball of the foot and reinforces the arch. The plantar fascia is placed under tension every time the foot hits the ground as the body weight is loaded through the leg. Microtrauma to the plantar fascia results in a painful condition known as plantar fasciitis which makes even basic walking excruciatingly painful, something athletes often describe as "walking on broken glass." Plantar fasciitis often develops into a chronic condition. When severe, it can sideline athletes for weeks or even months.

Turf toe: Turf toe typically results from hyperextension of the big toe and is an injury to the tissue surrounding the joint where the base of the big toe meets the ball of the foot. Ligaments around the joint can become overstretched or torn, causing pain and swelling. The more damage to the ligaments and joint capsule, the more severe the injury. Players often describe it as feeling like a nail is being driven through the toe as they try to push off. An athlete needs to extend the big toe in order to push off the foot properly when running; consequently the athlete's entire body weight is over that joint just prior to the foot leaving the ground. Chronic turf toe can become very disabling and in some cases has prematurely ended athletes' careers.

Lisfranc sprain: Lisfranc refers to an area of the foot where the long bones of the forefoot (metatarsals) articulate with the small (tarsal) bones in the middle of the foot. This joint is called the tarsometatarsal or Lisfranc joint. One mechanism of injury occurs as an athlete is running forward with his weight on the ball of his foot and he gets hit or stepped on from behind against his heel. The resultant force through the midfoot (the portion of the foot in between the ball and the heel) causes it to buckle, resulting in injury. It can also result from shearing forces at the foot, the result of a twisting injury when the forefoot remains planted and locked into the ground as the player moves in another direction. Mild sprains can resolve within a few weeks with rest and rehabilitation; more serious injuries (which can involve fracture and dislocation) require surgical repair and upwards of six months of recovery.

Achilles tendon: This large tendon anchors the calf muscles to the heel (calcaneus). Acute inflammation of the tendon (tendinitis) is common in athletes who participate in running and jumping sports. Chronic irritation (tendinosis) results in changes to the cellular structure of the tendon, rendering it more brittle, less flexible and often the source of more discomfort. Tendinosis is much more resistant to treatment. If there is excessive load placed upon the Achilles tendon, particularly if it is already damaged or diseased, it is susceptible to rupture. The moment the Achilles tears is often quite dramatic in that the athlete immediately loses the ability to push off the foot. The injury can be accompanied by a loud pop or snap, and athletes often describe a feeling of being kicked or struck in the back of the leg, near the heel. Achilles tendon ruptures in athletes typically require surgical repair, and return to full sports participation often takes six to nine months, although that timetable can vary depending on the athlete and the demands of the sport. Most athletes returning from this type of injury say it takes them a full year to regain their speed and explosiveness.

Shoulder

Glenohumeral joint: The shoulder is composed of the clavicle (collarbone), the humerus (arm bone) and the scapula (shoulder blade). The joint typically referred to as the shoulder is the glenohumeral joint; the humerus interfaces with the glenoid fossa (relatively flat open-faced surface) at the side of the scapula. The glenohumeral joint is unique in the amount of movement that is available, which allows us to throw overhead and complete a near 360-degree arc of motion. With that mobility, however, comes less overall stability, one of the reasons dislocation (bones in the joint moving out of position relative to one another) is more common in the shoulder. Additionally, given the relative laxity or looseness of the glenohumeral joint, it relies on numerous ligaments and muscles along with the labrum and the capsule to help provide stability. Sports injuries at the shoulder occasionally involve fractures, but most often the injuries are to the aforementioned structures and threaten the overall stability of the joint.

Humerus: The long bone of the arm. The head or uppermost portion represents the ball and rests in the glenoid fossa (the "socket" portion) of the shoulder blade to form the glenohumeral or shoulder joint.

Scapula: The shoulder blade. The glenoid represents the "socket" portion of the scapula and articulates with the humerus to form the glenohumeral or shoulder joint. The four muscles of the rotator cuff originate here and a total of 17 muscles have attachments somewhere on the scapula. There are also several ligaments that connect the scapula to the humerus (arm bone) and to the clavicle (collarbone).

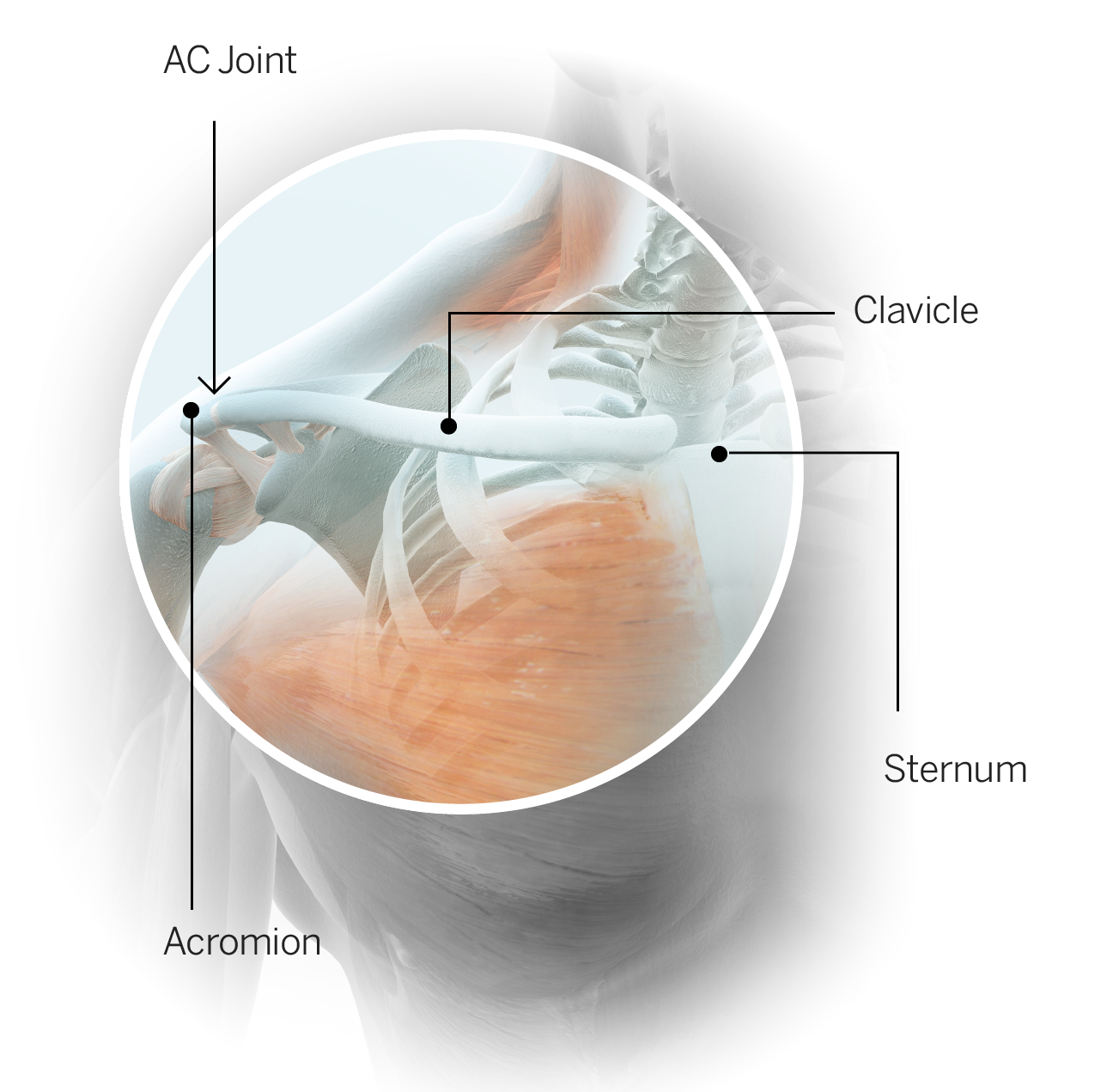

Clavicle: The collarbone. The clavicle is anchored on one end to the sternum or breastbone and on the other end to the scapula or shoulder blade. The clavicle and scapula (via the bony projection called the acromion) are connected by several ligaments to form the acromioclavicular joint, commonly referred to as the AC joint. A fracture of the clavicle is usually the result of a fall onto the point of the shoulder or a forceful direct blow. The majority of clavicle fractures in athletes happen in the middle third of the bone. Treatment can be nonoperative or operative depending on several factors, including the type and location of the fracture, the requirements of the athlete's sport and the physician's and athlete's preference.

AC sprain: An injury to the ligaments at the acromioclavicular joint is referred to as an AC sprain. Sometimes this injury is referred to as a shoulder separation because if the ligament damage is significant -- the clavicle will lift up, or separate, relative to the scapula. An AC sprain makes it particularly difficult for an athlete to raise the arm overhead; movements across the body also can be difficult. Lower-grade sprains typically recover with rest and rehabilitation, but a complete or Grade 3 separation is sometimes treated with surgical repair.

Shoulder dislocation: Glenohumeral (shoulder) dislocation occurs when the humerus (arm bone) slips out of position relative to the socket (glenoid). Dislocation can occur in a forward (anterior), downward (inferior) or backward (posterior) direction, usually as the result of trauma. The goal initially is to restore normal alignment by reducing the dislocation (repositioning the arm in the socket). The recovery time and the determination of whether surgery is required depend on the extent of tissue damage incurred during the injury. Subluxation occurs when the humerus moves beyond its normal range relative to the scapula but does not completely dislocate. In cases of subluxation, the athlete may feel a "slipping" sensation, but there is no deformity and the normal alignment is immediately restored.

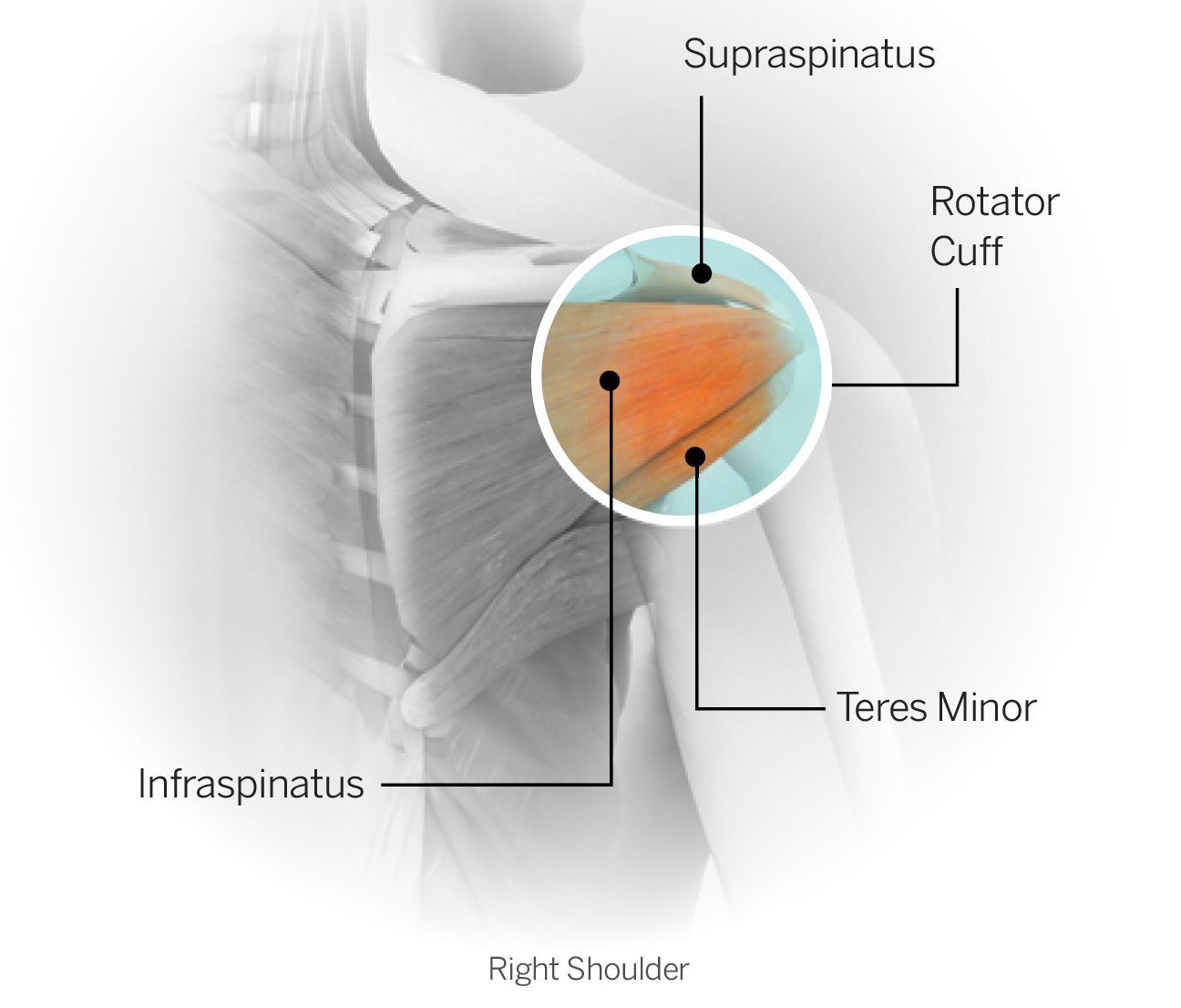

Rotator cuff: The rotator cuff is a group of four muscles: the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis. All four originate on the scapula (shoulder blade) and come together to form a common tendon, the rotator cuff tendon, which attaches on the humerus (arm bone). The primary function of the rotator cuff is twofold: to enhance stability of the shoulder joint and to coordinate the movement of the arm during overhead activities, such as throwing. The cuff muscles are small but their integrated function is critical to normal shoulder movement. An injury to any one of the muscles themselves or an injury to the common tendon can be painful and, more importantly, can compromise an athlete's normal movement as well as the functional stability of the shoulder. Rotator cuff tears typically refer to tears of the tendon, and they can be either acute or degenerative. Acute tears usually result from a single traumatic event such as an awkward fall or aggressive hit to the shoulder. Degenerative cuff tears happen over a period of time as the result of wear and tear due to repetitive motion, especially overhead. Overhead throwers such as pitchers and quarterbacks are particularly susceptible to degenerative cuff tears. In many cases, early degenerative changes are present in these athletes and may not cause any symptoms until a specific incident aggravates the condition. When a surgical rotator cuff repair is necessary, the prognosis depends on the athlete's overall health, the quality of the tissue at the time of surgery and the nature of the sport to which the athlete is returning. Generally speaking, recovery time for clearance to full activity ranges from six to nine months, but a return to peak performance can extend beyond that window.

Labrum: The labrum is a fibrocartilage ring that attaches to the glenoid (socket portion of the shoulder). It helps enhance overall stability of the shoulder. The labrum is subject to tearing and fraying, either from an acute injury (such as a dislocation) or chronic wear and tear (such as occurs with an overhead-throwing athlete). An injury to the labrum can cause pain and instability. The labrum does not have a good blood supply and will not heal independently. Not all labral injuries require surgery, but when they do the types of surgery vary. For minor damage, a debridement or "clean-up" procedure will suffice. A more extensive repair requires the rehab program to proceed more slowly. Return to sport depends on the extent of surgery, the health of the athlete and the nature of the sport but often requires a minimum of three to four months.

Biceps: The biceps muscle has two tendinous attachments in the shoulder region; both are located on the scapula. It travels down the arm and inserts just below the elbow. The biceps is responsible for flexing the elbow and rotating the forearm in the palm-up direction (supination) and is thought to have a small contribution to shoulder stability. Fraying or tearing of the biceps tendon in the shoulder region can cause pain and loss of functionality for overhead athletes in particular.

Elbow

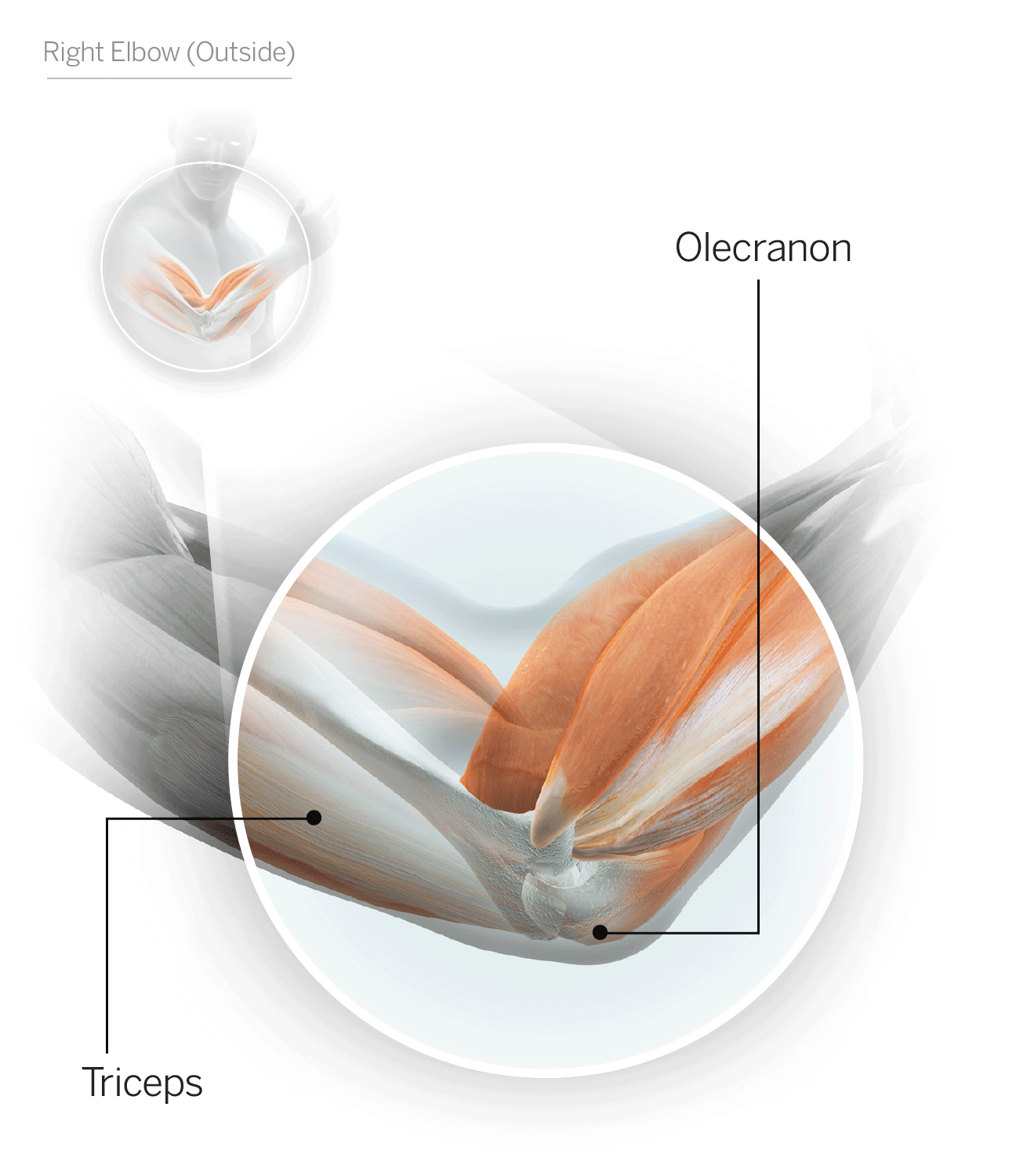

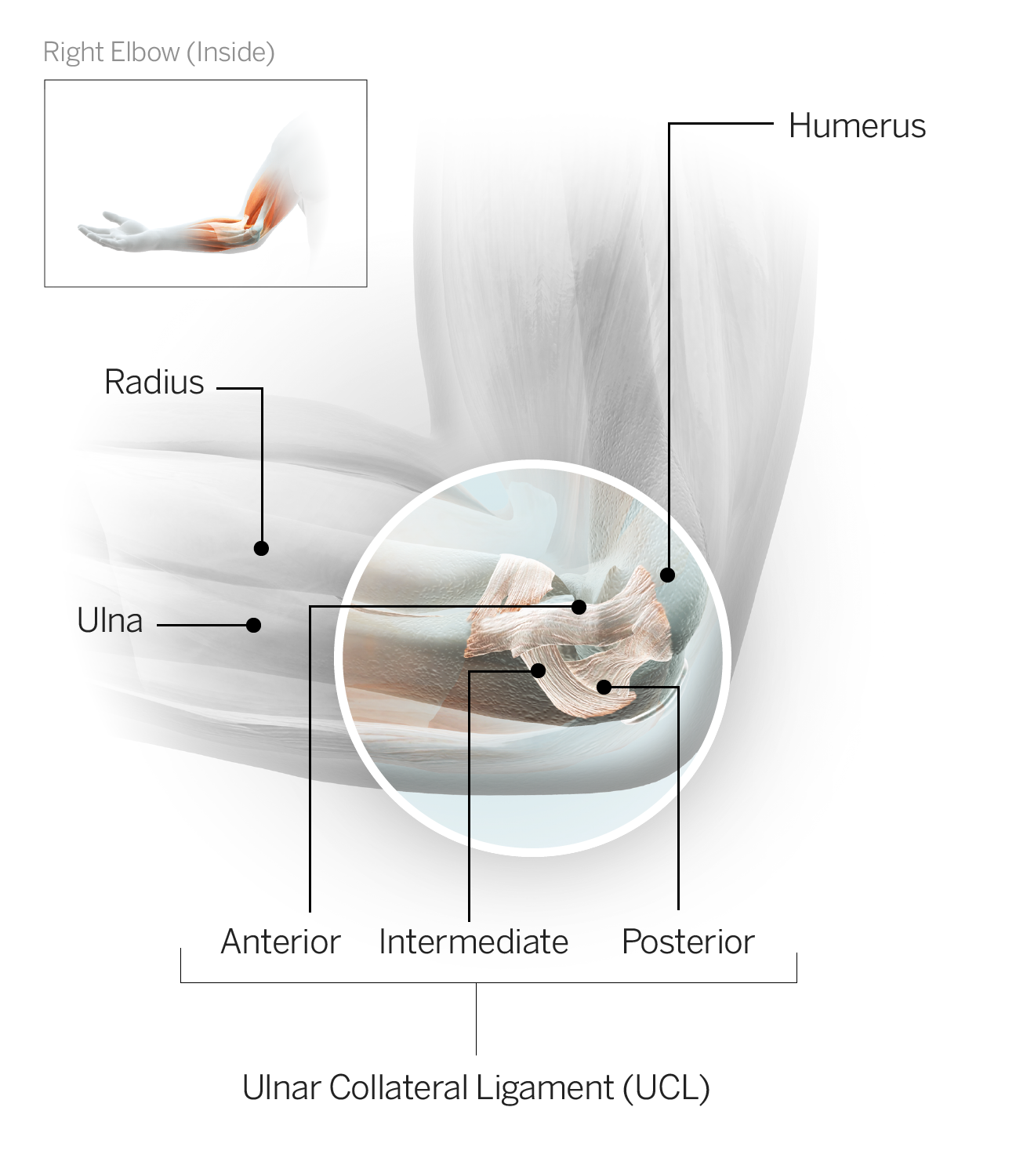

Ulna: One of the two bones of the forearm. It runs along the medial (inner) side of the forearm. The ulna interfaces with the humerus (arm bone) and the radius (other forearm bone) on the near end to form the elbow joint.

Radius: One of the two bones of the forearm. It runs along the lateral (outer) aspect of the forearm. The radius interfaces with the humerus (arm bone) and the ulna (other forearm bone) on the near end to form the elbow joint.

UCL: The ulnar collateral ligament sits on the medial (inner) side of the elbow and connects the medial forearm bone (ulna) to the arm bone (humerus). A tear of the UCL is an injury most often seen in baseball pitchers as a result of repetitive wear and tear and typically requires surgical repair. Rehabilitation is lengthy following UCL repair, and the standard time frame for a return to competitive throwing is 12 to 18 months.

Hand

Metacarpal: The five long bones running from the base of each digit (all fingers and the thumb) to the wrist. The metacarpals are ordered numerically based on their position in the hand; the first metacarpal runs from the thumb to the wrist and so on to the fifth metacarpal, which runs from the pinkie finger to the wrist. The most common injury to a metacarpal is a fracture. Treatment may be casting or surgery, depending on the specifics of the injury, among other variables. Recovery time varies depending on the treatment approach and the athlete's individual healing.

Illustrations by Bryan Christie