The Philadelphia 76ers mobbed Furkan Korkmaz after his winning buzzer-beater in Portland on Nov. 2, but what they have cherished more than the win is the night that unfolded afterward. Tobias Harris organized a gathering at a local club to celebrate. Every player on the trip came but Al Horford, who says he was more or less a DNP-OLD.

They toasted Korkmaz. At one point, Josh Richardson approached Korkmaz and asked what he was feeling. "This is the best day of my life," Korkmaz replied with an earnestness that surprised Richardson. Mike Scott raised his voice an octave to imitate Korkmaz's giddiness in a separate conversation at the club: "'I never felt like this beforeeeeeeee!'"

Three nights later at the Grand America Hotel in Salt Lake City, Ben Simmons texted his half-brother, Sean Tribe, to see what he was up to. Tribe responded that Richardson and Joel Embiid were watching the Chicago Bulls-Los Angeles Lakers game with some team staff in the hotel lounge, and suggested Simmons join. Simmons came and watched with Embiid as LeBron led a huge comeback. It struck several people -- including Simmons -- that such a gathering would not have happened last season.

"Definitely," Simmons told ESPN. "The chemistry is much better. Guys are giving up their time to bond."

After Game 7 of their epic series against the Toronto Raptors, the parent of one Sixer confided to higher-ups that the team's chemistry felt off, sources say -- that they seemed like a group that would rather ride home in separate cars.

Kawhi Leonard's epic four-bounce shot plunged those Sixers into the unknown. Three starters -- Harris, JJ Redick, and Jimmy Butler -- entered free agency. Philly had given up two popular Process holdovers -- Robert Covington and Dario Saric -- for Butler in the first of two mega-trades that roiled the roster. In the playoffs, he became the centerpiece of their offense.

But on June 30, there was no five-year maximum offer for Butler, multiple sources say. Perhaps the Sixers pivoted after learning of Horford's interest in joining. Perhaps they were concerned about tension between Butler and some within the team, including on the coaching staff. Maybe those two things were interrelated. Like every team chasing Butler, they probably wondered how he would age.

They effectively replaced him with Horford and Richardson on long-term deals. Every key player is under contract for at least the next two seasons. Finally, calm.

After years of absurdist drama -- the Process, the resignation letter, Markelle Fultz, the Bryan Colangelo Twitter scandal, last season's roster upheaval -- the Sixers are counting on a new tranquility to grease the team's development.

Harris and Horford are ringleaders in organizing dinners. Attendance has been robust -- "sometimes 14 or 15 guys," Harris says. He and Horford are Michelin star aesthetes. At the upscale Italian restaurant Barolo Grill in Denver, some younger teammates joked they could not read the menu, Harris says. Embiid is a steak guy. Harris has resolved (for now) to just pick the best steakhouse in each city.

"That stuff is important," Horford says. "The longer you advance, the more you need everyone connected." Maybe some bond formed deep in the night will spur the hard conversation that nudges Simmons into shooting jumpers, or Embiid into focusing even more on his conditioning.

Then again, despite whatever strains hovered last season, the Sixers might have been one bounce from the conference finals -- perhaps from a championship.

Good vibes are fragile. If Philly's offense -- 16th in points per possession -- flounders, caught between tentpole stars who don't yet complement each other, the inevitable frustration could create fissures. The relationships that really matter are those between Simmons, Embiid and coach Brett Brown.

"You really find out about culture," Harris says, "when you drop five games in a row."

On the Sixers' practice court, Brown sometimes outlines two rectangular areas along the baseline on either side of the paint, extending a few feet toward each corner and up to the foul line. Brown calls it the "low zone," aka the dunker spot, and it is where Simmons should often be when he's not handling the ball or spotting up. It is an imperfect solution to the Sixers' defining structural issue: Their point guard can't, or won't, shoot. (His free throw attempts have also dropped by almost half, slightly alarming.) Hanging in the low zone is a way of keeping Simmons productive -- as a lob threat, cutter, offensive rebounder -- when he is otherwise in the way.

Brown and Simmons both harbor ambitions for Simmons well beyond the low zone. Brown says he has designed plays specifically for Simmons to shoot corner 3s; Simmons had taken none until draining his first career triple against the Knicks Wednesday night. "I want him in the corners," Brown says. "I want him shooting 3s -- on his time frame."

But if Simmons arrives in the low zone, he needs to stay there, Brown says. "Two inches outside that, and it's the dead zone," Brown says. "You're killing plays. You're in Joel's way. You will either be in the corner, or the low zone. Anything else is unacceptable."

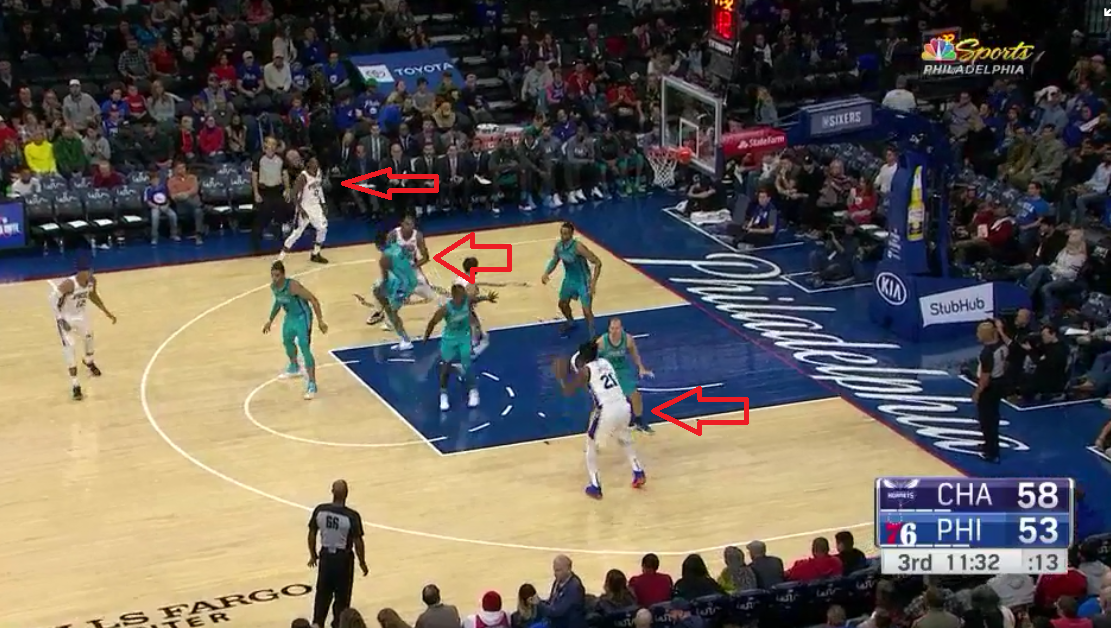

Simmons sometimes drifts into that dead zone:

That makes it easier for Simmons' man -- Royce O'Neale below -- to clog the paint:

And Philly has a lot going on in the paint. The Sixers lead the league in post touches. That is baked into their jumbo-sized team. Horford can shoot, but he likes bulldozing undersized power forwards. Philly's starting lineup features four post threats, and on some nights -- against the Atlanta Hawks and Trae Young, for instance -- Brown will call post-ups for Richardson, too.

"We are so different, and that really intrigued me," Horford says. "But there are times when we are all trying to get to the basket."

The Sixers knew it would start out clunky. They have to pay more attention than any other team to who stands where. Possessions can look mechanical as each player jogs to his starting point. Brown is calling more plays than he'd prefer. Embiid spends too much time on the perimeter for his taste. "I don't like shooting 3s," he told ESPN before the season, "but if I gotta help Ben -- if I gotta give him space -- I will."

The Sixers hope time brings flow; between suspensions, injuries and rest days, their starting five has played only 70 minutes in six games. That group has obliterated opponents by 18 points per 100 possessions, with elite marks on both sides of the ball.

More broadly, the Sixers are betting on defense to paper over inconsistent scoring. Philly ranks 10th in points allowed per possession, but as they coalesce, they should smother teams. They already allow the fewest 3s in the league.

The Sixers are almost built to render the whims of shooting irrelevant. Defense travels. They are tied for fifth in offensive rebounding rate and rank first in defensive rebounding. When Embiid plays, they earn heaps of free throws. How much does shooting really matter if you rebound 30% of your own misses, generate tons of free points, and provide the opponent very few second chances?

That equation tips further in Philly's direction when those long arms snare turnovers. Steals fuel Simmons' transition game. The Sixers get shots up before their spacing ossifies.

There is an unavoidable dissonance between how a team built around Simmons would play compared to a team built around Embiid. The Sixers' internal data indicates Embiid trails the play on 90% of possessions, Brown says. He cautions Simmons about sprinting Embiid out of the offense. "The game can sometimes run past Joel," Brown told ESPN last season.

Running off steals and misses gives Simmons selective control -- ownership. Simmons usually defends smaller guards, and he is devastating mowing them over in semi-transition before the opponent rejiggers matchups:

Philly ranks 13th in opposing turnover rate -- not quite good enough considering they are leaking turnovers; only three teams have coughed it up more often. The turnover battle is going to be a more important barometer for Philly than for any other team.

Signing Horford also addressed their biggest liability from last season: surviving Embiid's minutes on the bench. Brown maps his rotation around player pairings. So far, he has tethered Embiid to Richardson, and Simmons to Horford. Harris floats between groups.

In Horford, Simmons has a versatile pick-and-roll partner when Embiid rests. The rotation ensures that in their solo minutes, Simmons and Embiid have four capable shooters around them. Philly is already plus-33 in 179 minutes when Simmons and Horford play sans Embiid, per NBA.com. They were minus-140 in 1,200-plus Simmons-only minutes in the 2018-19 regular season, and an ungodly minus-76 in 138 playoff minutes.

Philly's four-out spacing in those Embiid/Simmons-only minutes falls away when Matisse Thybulle plays; Thybulle is 8-for-25 on 3s, and his misses can be ugly.

Brown faces tricky decisions splitting the last rotation spot between Thybulle, Korkmaz and one of the Raul Neto/Trey Burke duo. Korkmaz is in the lead. He's shooting 37% from deep, working a more confident off-the-bounce game, and moving his feet on defense.

Everything changes if Thybulle's 3-pointer arrives in time for the playoffs. (He is already wrecking stuff on defense.) Expect season-long internal debate about whether the Sixers should add shooting. On bad nights, it can appear a dire need; only eight teams have attempted fewer 3s as a portion of all attempts. Marco Belinelli and Ersan Ilyasova famously sparked Philly two seasons ago. Redick and Landry Shamet are gone.

But almost everyone around Simmons and Embiid is a capable and willing 3-point shooter.

(An aside regarding Thybulle's growth curve: The Sixers overhauled their player development operation in the offseason. They now have 11 coaches and staff devoted strictly to player development -- an entirely separate coaching wing that does not participate in game planning. That is probably unique in the NBA.

They have so many coaches, Brown took the unusual step of excising some -- the player development group, some strength and conditioning personnel -- from his film sessions. That decision tears at Brown. "I don't feel right about it," Brown says. "I want the young coaches to hear my voice. But you reach a point where there are just too many people." Team sources insist the decision is unrelated to leaks last January about Butler questioning Brown at a film session.)

The fringe stuff is interesting, but Philly will rise or fall with Simmons and Embiid together. They don't know what that offense looks like during crunch time. The Sixers see opportunity in that uncertainty. Their Butler-centric offense was a fallback. After so much turnover, they didn't have time to discover a cohesive identity.

Most teams would put their best ball handler in pick-and-roll. The Sixers haven't with Simmons. You can't screen a defender who isn't there.

A lot will flow from Embiid post-ups. That is tough sledding against playoff defenses that won't double in ways that yield easy one-pass-away 3s. The math on these shots is unfriendly, even for Embiid:

When Embiid is tired, he can't truck opposing centers as easily.

"It's harder in the playoffs," Embiid told ESPN in September. "Space gets tighter. Defenses dig more."

Some coaches would spot four players up around the arc while Embiid goes to work. Instead, Brown has them cutting and screening everywhere:

That can clutter Embiid's space, and confuse his outlet reads; Embiid has been turnover prone his entire career. But that motion is also a concession to Simmons. If Simmons isn't spotting up -- if he's in the low zone -- Embiid's space is already constricted. Motion turns Simmons into a threat. Off-ball screens spring open shooters:

"I want it all -- movement and space," Brown says. "But how do you have it all? It's hard. We're getting there. Post offense will be the most weighted part of our offense. We'd better be good at it."

Embiid spent the summer honing his off-the-bounce game to be less dependent on post play in crunch time, he says.

Harris is also going to get plenty of chances. With Embiid, Horford and Simmons on the floor, opponents have to defend Harris with smaller players. During the offseason, he enlisted any smaller player he could find -- "college players, overseas dudes, random guys" -- to guard him one-on-one in simulated late-game settings. Harris ordered those players to foul him so he could work on playing through contact.

The results have been uneven. Harris smushed Collin Sexton in Cleveland on Sunday but has had trouble dislodging other guards. He's a hit-or-miss playmaker when help comes.

In a small sample, Philly's crunch-time offense ranks in the middle of the pack. On good nights, they brute force their way to points. On bad nights -- like their overtime loss Friday in Oklahoma City -- the offense is slow and unsure of itself. After that game, Brown and his starting five discussed the idea of Brown marching on the floor to call impromptu timeouts when late-game possessions stagnate, Brown says.

Philly is experimenting with other looks. The Sixers have gotten mileage out of Richardson-Embiid pick-and-rolls with Simmons high on the wing:

Simmons is an explosive cutter with smart timing. He can punish defenses who ignore him out there. Embiid is rolling to the rim more often this season, sucking help away from shooters.

Philly has also used Simmons as a screener for Richardson, with everyone else -- Embiid included -- spaced around the arc:

That same action can work with Embiid in the low zone: Simmons becomes Draymond Green, rampaging into 4-on-3s and hitting Embiid for alley-oops.

Richardson will be the hiding place for the opponent's smallest, weakest defender. Involving him in screening actions with Simmons -- or anyone in Philly's starting five -- forces opponents into a painful choice: switch into mismatches, or trigger rotations that unlock open 3s. Philly has barely scratched the surface of using Richardson this way. It is the kind of slowdown, predatory basketball that rules the playoffs.

It is also how playoff teams hunted Redick. The Sixers knew they were sacrificing a unique shooter by letting Redick walk. They are betting on what they gained being more powerful in the postseason: a defense without any exploitable weak link.

Teams that can play small and fast, with tons of shooting -- Boston and Milwaukee come to mind -- will test that defense. Even if the Sixers prove up to the task, defense alone won't carry them all the way.

Simmons and Embiid may never make for a snug fit on offense. Fit isn't everything. Talent matters. Supernova talent can zoom through corridors too narrow for regular players. It smashes well-intentioned schemes.

But the talent gap shrinks in May and June. With Butler gone, the Sixers need to craft a failsafe offense. The clearest path there involved Simmons expanding his game. That hasn't happened yet.

There will be games for Philly, maybe weeks, when it feels as if growth is not coming. That is when frustration and resentment can break teams apart. If culture, camaraderie, and stability matter, it will be in those moments.

Horford is a rock. He senses his basketball mortality. New teammates are surprised how much he is speaking behind closed doors. As Horford went to ring the ceremonial victory bell in Philly's locker room after the Nov. 10 win over Charlotte, teammates surrounding him, he paused, holding the rope attached to the clapper. Charlotte's reserves had trimmed the lead to five in garbage time.

"Next man up has to be ready," Horford told the group. "Doesn't matter if it's the first quarter or the fourth quarter. Be ready." Ding.

"When he speaks," Scott says, "everyone listens."

Holdover players say the team seems angrier after losses. When Harris boarded the team bus after Philly's Nov. 6 loss in Utah -- their second straight -- he was stunned by the brooding. "You would have thought someone's parents died," he says. "But you know what? That's a good thing. We came so close last year. We're focused now. This is a championship team with championship goals."