Edmonton Oilers center Connor McDavid's season ended on April 6 when he slid into the post of the Calgary Flames' net, injuring his left knee severely enough that he was unable to bear weight on it and had to be helped off the ice. Given that this also happened to be the Oilers' season finale, fans looking ahead to next season were left with questions about what to expect for McDavid come September.

In the days since the injury, it has been widely reported that McDavid suffered a posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) tear that would not require surgery, and he is expected to be ready for training camp in September. Considering the anatomy of the PCL, the nature of the injury, the demands of the sport and, above all, the athlete himself, there is certainly reason for Oilers fans to be optimistic.

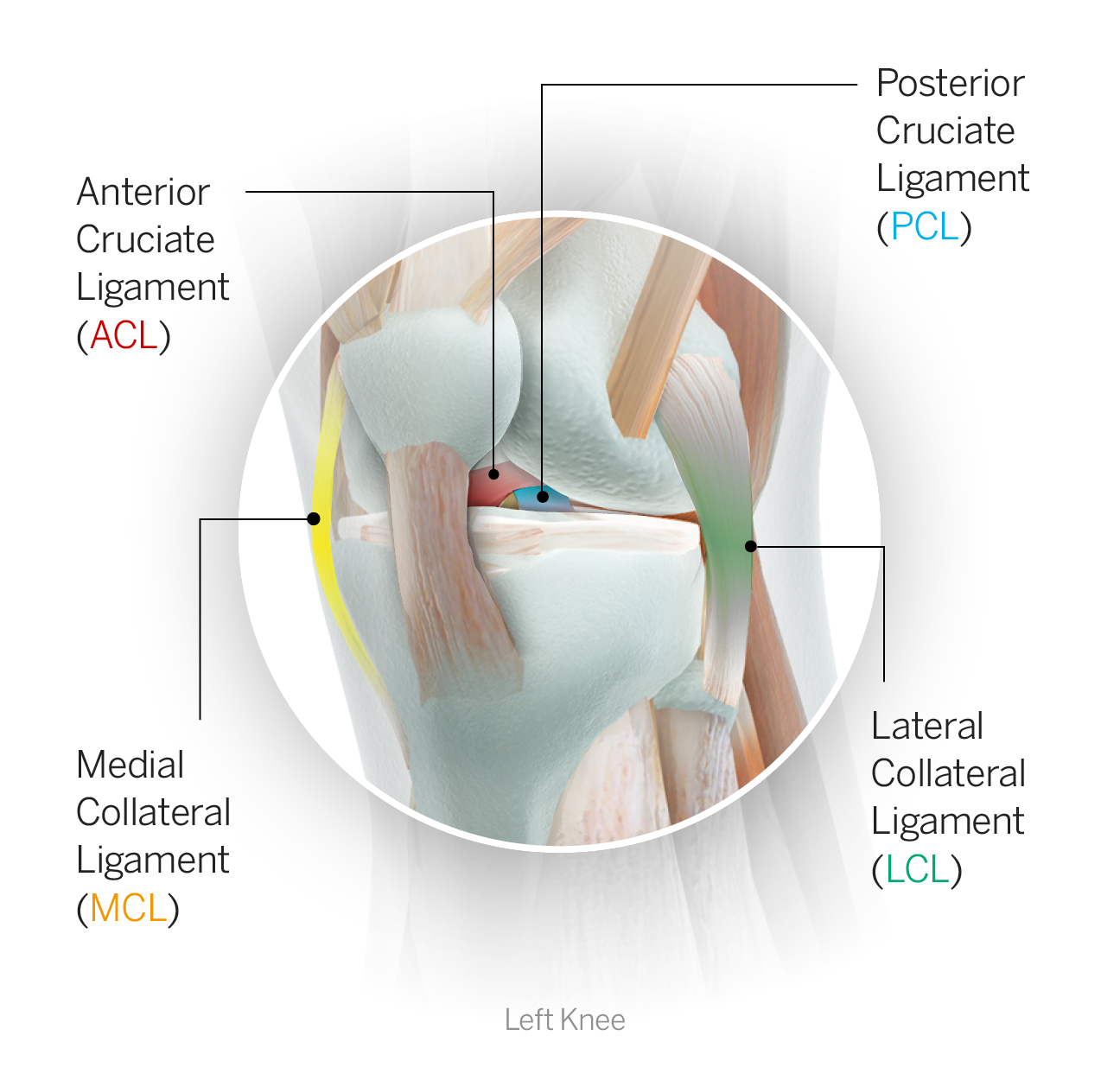

The PCL is a thick ligament that constitutes one of the four primary stabilizing ligaments of the knee. It is situated behind the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deep within the joint, running between the tibia (shinbone) and the femur (thighbone). The two ligaments cross each other (hence the name cruciate, or cross) and provide rotatory and translational (anterior to posterior) stability to the knee. The other two main knee-stabilizing ligaments, the medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL), sit on either side of the knee joint and contribute primarily to side-to-side stability.

Perhaps the most common mechanism of injury for the PCL is a direct blow or fall onto the knee. The tibia is forced backward on the femur resulting in damage to the ligament. This injury was once frequently referred to as the "dashboard injury," as it would often be the result of a person's knee encountering the dashboard in a high-speed motor vehicle accident. (With the advent of airbags, this mechanism is now far less common.)

McDavid's injury was similar to the dashboard mechanism. After he was tripped up by Flames defenseman Mark Giordano, McDavid came sliding into the post at a high rate of speed. The impact location just happened to be at the level of his knee joint, forcing his tibia backward on his femur and injuring his PCL. After the injury, McDavid said he felt as if his leg was in two pieces, likely a reflection of the sensation of instability associated with this type of injury.

Although the severity of the ligament injury has not been reported, PCL injuries in isolation (meaning not accompanied by other structural injury) rarely require surgery; the ligament is often able to heal on its own provided it is protected from extremes of motion. Prognosis for returning to an elite level of play is high following a proper course of rehabilitation, which was set to begin immediately for McDavid, according to a statement released by the Oilers.

The silver lining here is that the injury was not to McDavid's MCL, a ligament far more frequently injured in hockey players and perhaps more critical to their ability to perform at an elite level. The MCL specifically helps control medial-lateral stability, an essential element of being able to balance on a blade that is just a few millimeters thick while traveling at high speeds and frequently changing direction. The nature of the sport is such that it places high demand on the MCL, and instability in this plane of motion can severely compromise the athlete. While many hockey players sustain MCL injuries and recover fully, the threat of the consequence of a significant MCL injury is more immediately worrisome than that of one involving the PCL, particularly if the injury is of lesser severity.

The key to any athlete's successful recovery following a PCL injury requires giving the ligament the best opportunity to heal, specifically avoiding excessive shear forces while it is trying to repair itself. To that end, the athlete is typically braced early in the recovery period to help control range of motion. Early strengthening ensues, with heavy emphasis initially on the quadriceps (large muscle group on the front of the thigh) as it helps control excessive posterior shear. Conditioning and core strengthening are an integral part of the rehab process and, as healing progresses, the athlete's range of motion expands, as do the strengthening parameters. Balance, coordination, agility drills, return to skating and hockey-specific activities are integrated throughout the progression toward return to play.

It is always helpful to look for a comparable injury and recovery scenario within the sport. Given that PCL injuries are relatively uncommon in ice hockey, there aren't big numbers to draw from, but Boston Bruins defenseman Zdeno Chara suffered an isolated PCL injury in October 2014 and, like McDavid, his injury did not require surgery. He was able to return to the ice roughly two months later, but acknowledged at the end of the season that it took him a while to feel like himself again.

With nearly five months until the start of the next hockey training camp, there should be ample time for McDavid to recover and be ready to participate. Beyond the factors that make returning from this injury favorable, the combination of his young age (22), his overall health (McDavid fractured his collarbone in 2015 but has otherwise avoided major injury during his professional tenure) and his elite talent bodes well for McDavid's ability to return to MVP-caliber status.