On July 23, 1966, in a World Cup quarterfinal in front of 40,248 at Everton's Goodison Park, Portugal and North Korea played one of the most frantic and celebrated matches in soccer history. Led by the brilliant Eusebio, playing in his only World Cup, the Portuguese had torched Hungary, Bulgaria and a disappointing Brazil by a combined 9-2 to advance to the knockout rounds, while North Korea had finished a surprising second in their group, losing badly to the Soviet Union and drawing with Chile before shocking Italy, 1-0, in Middlesbrough and eliminating one of the tournament favorites.

The North Koreans continued riding the wave of underdog energy early on. In a quick transition during the first minute of the game, Im Seung-Hwi fired off a shot from long range; it was blocked, but landed at the feet of Pak Seung-Zin, who scored from a closer distance. They kept going. In the 22nd minute, Portugal keeper Costa Pereira misplayed a cross, which quickly led to a tap-in for Lee Dong-Woon and a 2-0 lead. Two minutes later, it was 3-0.

However, the upstarts would quickly run out of gas. From the 27th minute on, Portugal attempted 22 shots to North Korea's four. Eusebio scored an incredible four goals in 33 minutes to give the favorites the lead, and Jose Augusto finished off a 5-3 win with a short-range finish in the 80th minute. Probably the best team in the tournament, the Portuguese fell victim to a pair of Bobby Charlton strikes and lost to the English hosts, and eventual champions, 2-1 in the semis.

- World Cup 2022: News and features | Schedule | Squads

Thanks to some brilliant archival work, you can watch extended highlights of the match on FIFA's website. (You'll also quickly come to realize how far ahead of his time Eusebio really was.) You can read more about it here, and thanks to the work of the data collectors at Stats Perform, we can dive into the data, too.

The teams attempted 47 combined shots, 43% of which were on target and 51% of which were from inside the box.

The shots were worth a combined 4.4 xG (3.4 for Portugal, 1.0 for North Korea), or 0.09 per shot.

Portugal had possession 57% of the time, a little bit above its tournament average of 52%.

Each team racked up 125 possessions. Portugal began its possessions an average of 38.6 meters up the pitch, while North Korea averaged 26.1 meters.

The teams attempted 795 total passes (Portugal 442, North Korea 353) and completed 72% of them (78% for Portugal, 65% for North Korea). Portugal attempted 48 crosses to North Korea's 10; both teams completed about 30% of them.

Portugal started 7% of its possessions in the attacking third and finished 57% of them there. North Korea: 2% and 30%, respectively.

Fifty-five years and about four months later, in front of 39,641 at the same venue, Liverpool beat Everton 4-1. The game featured far fewer shot attempts (16 for Liverpool, eight for the underdog Toffees), but 58% of them came from inside the box, and they were worth a combined 4.0 xG -- 0.17 per shot, nearly double that of Portugal-North Korea. The teams attempted 868 passes, 9% more than Portugal-North Korea, and completed 76%. Liverpool completed 82% of its passes, while dominating 68% of possession. The teams attempted only 33 combined crosses and completed just 18% of them.

The teams each possessed the ball 116 times, a dramatic departure from the Premier League's season average of just 93.2. Liverpool began its possessions 38.5 meters up the pitch, starting 10% of them in the attacking third and finishing 38% of them there; Everton: 36.3 meters, 6% starting in the attacking third and 27% ending there.

Statistics tie a sport's present to its past. It gives us a language with which to communicate, evaluate and debate. It also provides a level of context that nothing else can.

A sport like baseball has been blessed with both this inherent understanding and an incredibly measurable sport. Basketball, too, albeit to a lesser degree. Soccer, however, is far less measurable and got a terribly late start. Stats Perform has data like this for major soccer leagues going back a bit more than a decade, but if you want to look up the stats from, say, the 1994-95 Premier League season or Liverpool's 1977 European Cup win over Borussia Monchengladbach, good luck.

Stats Perform did, however, provide us with a small miracle by logging World Cups, starting with England 1966. Through 14 tournaments, undertaken every four years, we have glimpses into how soccer has evolved and changed shape over nearly six decades. It may not be as much as we would want in a perfect world, but it is to be celebrated.

So how has the game evolved? Casual soccer fans probably already know a lot of the general answers -- the game is more possession- and passing-based, teams take fewer long-range shots, etc. -- but being able to tie anecdotal trends to actual data is a gift. Let's take advantage of it.

The possession game has indeed taken over

The 1974 Netherlands team is one of the most celebrated international squads in the sport's history. More than half the roster came from the clubs that had combined to win four straight European Cups -- Feyenoord (1970) and Ajax (1971-73) -- and it was captained by Ajax-turned-Barcelona star Johan Cruyff.

It was coached by the famed Rinus Michels and was known for Total Football, the Cruyff-driven and ball-dominant style that allowed players to switch positions in given contexts and quickly attack from any situation. The Dutch were the story of the tournament, plowing through two group stages with five wins and a draw to reach the finals but losing, 2-1, to Gerd Muller, Franz Beckenbauer and West Germany.

Thanks to Stats Perform's work, we have stats for both how that 1974 Netherlands team actually played and how much influence it may have had on how the rest of the world played.

The Dutch enjoyed 57% possession for the tournament: more than any team in 1966 or 1970, but not dramatically so. Their 4.3 passes per possession were fourth-highest in the tournament, and their 15.8% of possessions with 9-plus passes was second behind the West Germans. They had a lot of solo possessions (7.6%, sixth-highest), which doesn't fit the ball-domination style, and you could make the case that West Germany was the more patient overall team, although the Dutch ended up with 58% possession in the final, due at least in part to trailing for the entire second half. Their interchangeable nature didn't really show up in their team stats -- it's probably noteworthy that all 11 of their regulars in the tournament ended up with between 230 and 580 touches, and eight of them attempted at least nine shots -- but their passing volume numbers were not off the charts by any means.

Still, via Dutch influence or someone else's, the game had entered a more passing-friendly stage within a few years. It didn't show up in the 1978 data, but it had by 1982.

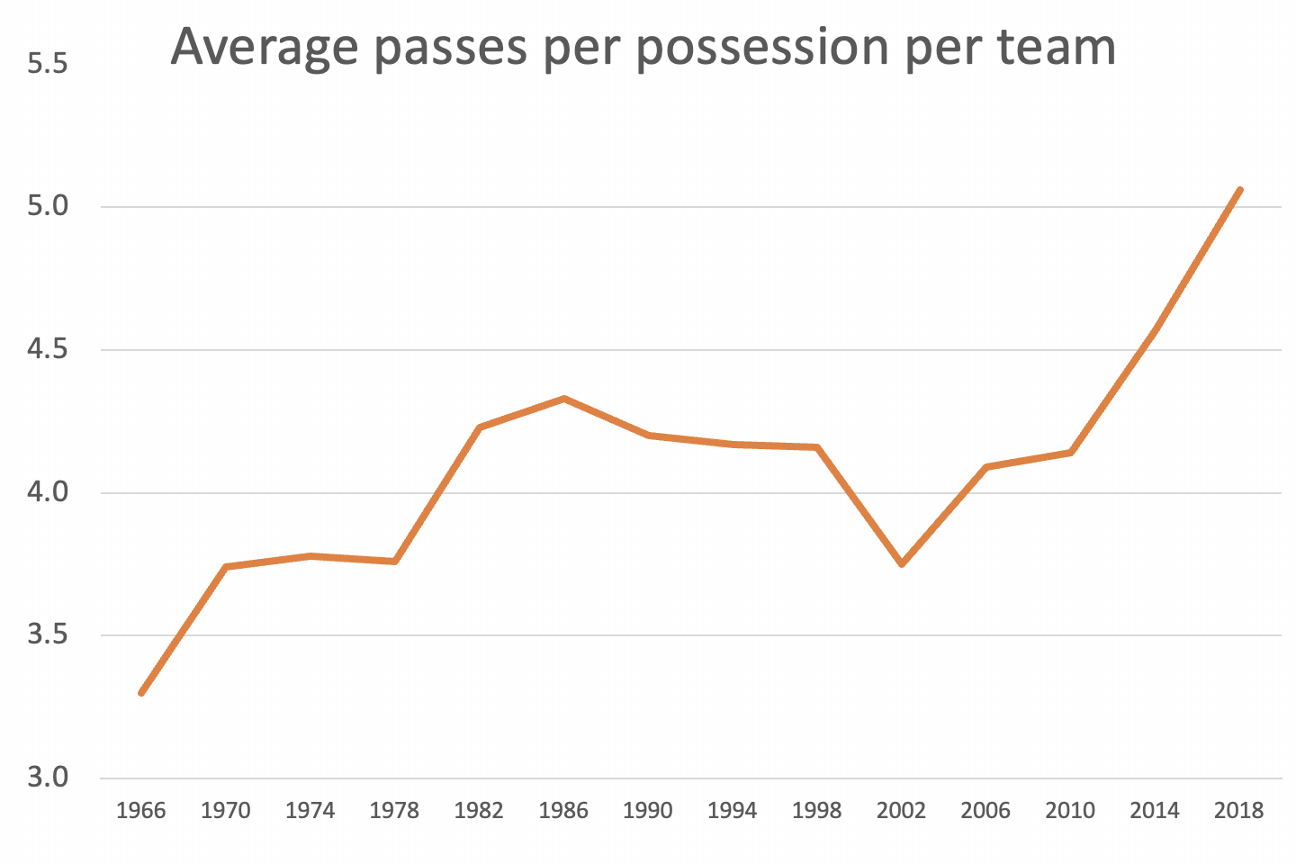

The 1970, 1974 and 1978 tournaments averaged 3.7 to 3.8 passes per possession per team, and aside from a weird dip in 2002 -- when 23 of 32 teams averaged under four, including both finalists (Brazil at 3.7, Germany at 3.9) -- every tournament from 1982 to 2010 averaged between 4.1 and 4.3. But following Spain's 2010 win (and the club dominance of Barcelona), that average ticked up to 4.6 in 2014 and 5.1 in 2018, when seven teams averaged over 6.0 and Spain averaged 10.0 while advancing to the round of 16 but suffering an upset to the host Russians.

A team ahead of its time: 1986 Morocco

While possession is often tied to talent advantages in the current game (and money advantages in the club game), this Moroccan team controlled 56% of the possession (most in the tournament) and averaged 5.5 passes per possession (second-most). With a squad composed heavily of players on the AS FAR team that had won the 1985 African Champions League, they basically played keep-away, dominating the ball but ranking just 17th of 24 teams in shots per possession and 23rd in xG per shot.

They won a tough Group F with scoreless draws against England and Poland and a 3-1 win over Portugal, and they controlled 60% of possession in their round-of-16 match against West Germany. The game nearly went to extra time, but Lothar Matthaus' goal in the 88th minute won it for the Germans.

Behold, the power of the back-pass. While there is a loose correlation between pass-heavy possessions and a slower tempo, soccer's overall tempo plummeted in the 1980s, in part because of a specific type of pass. The sport's history books will always reference 1992's banning of the back-pass -- in which a teammate would pass the ball back to the goalkeeper, who could pick it up with his hands and stall for a solid amount of time -- as one of the most impactful and viewer-friendly rule changes any sport has ever seen. The 1990 World Cup was notorious for its general unwatchability, and the back-pass was regarded as a major reason why.

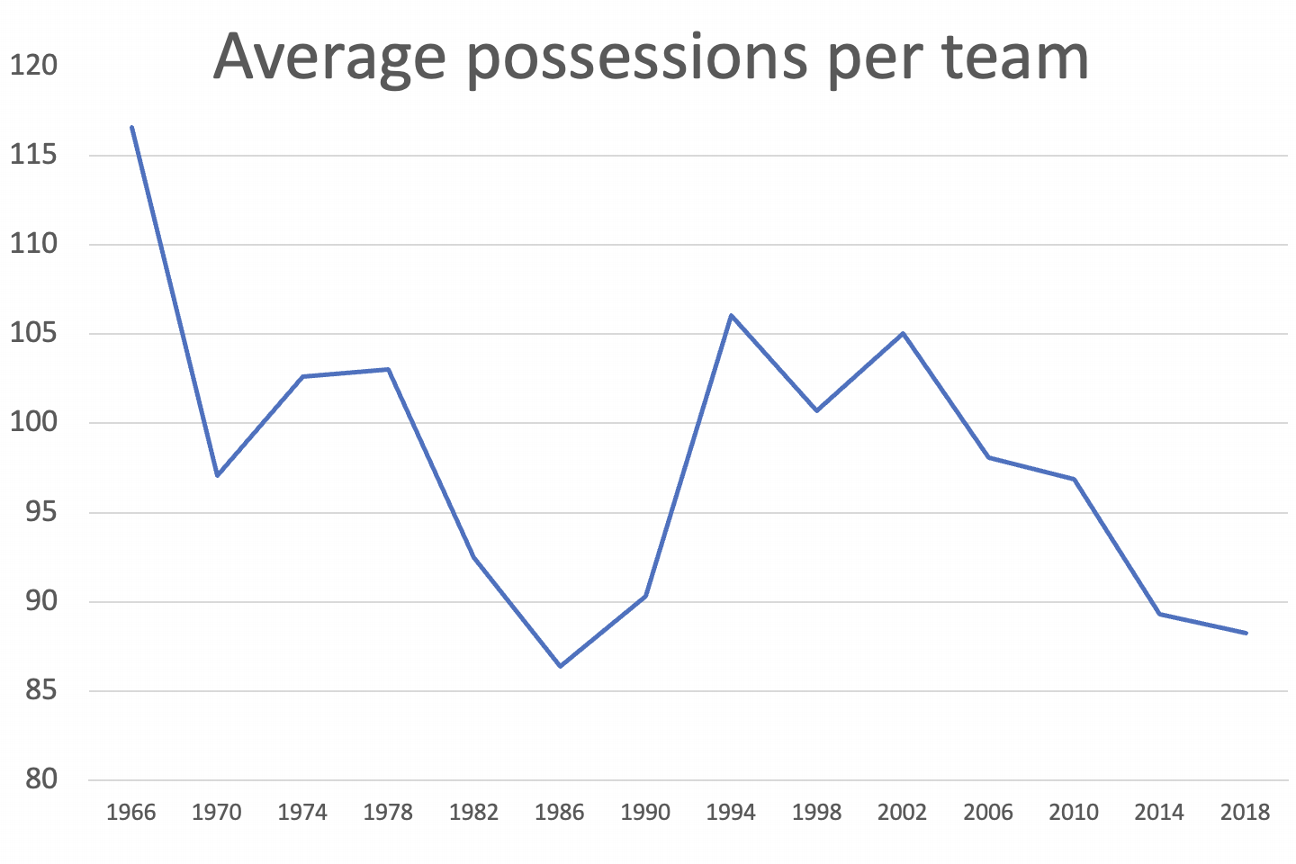

Without the average of passes per possession per team changing, average possessions leaped by more than 17%, from 90.3 in 1990 to 106.0 in 1994, the highest average since the manic 1966 tournament. That's quite an impact.

Beginning in 2006, overall tempo began to slow again -- this time due to the more patient passing and buildup approach that has defined much of the modern game -- and we can once again see the change heavily taking hold in 2014. Only the dreadfully slow 1986 tournament had a smaller average possession total (86.4) than 2014 (89.3) or 2018 (88.3).

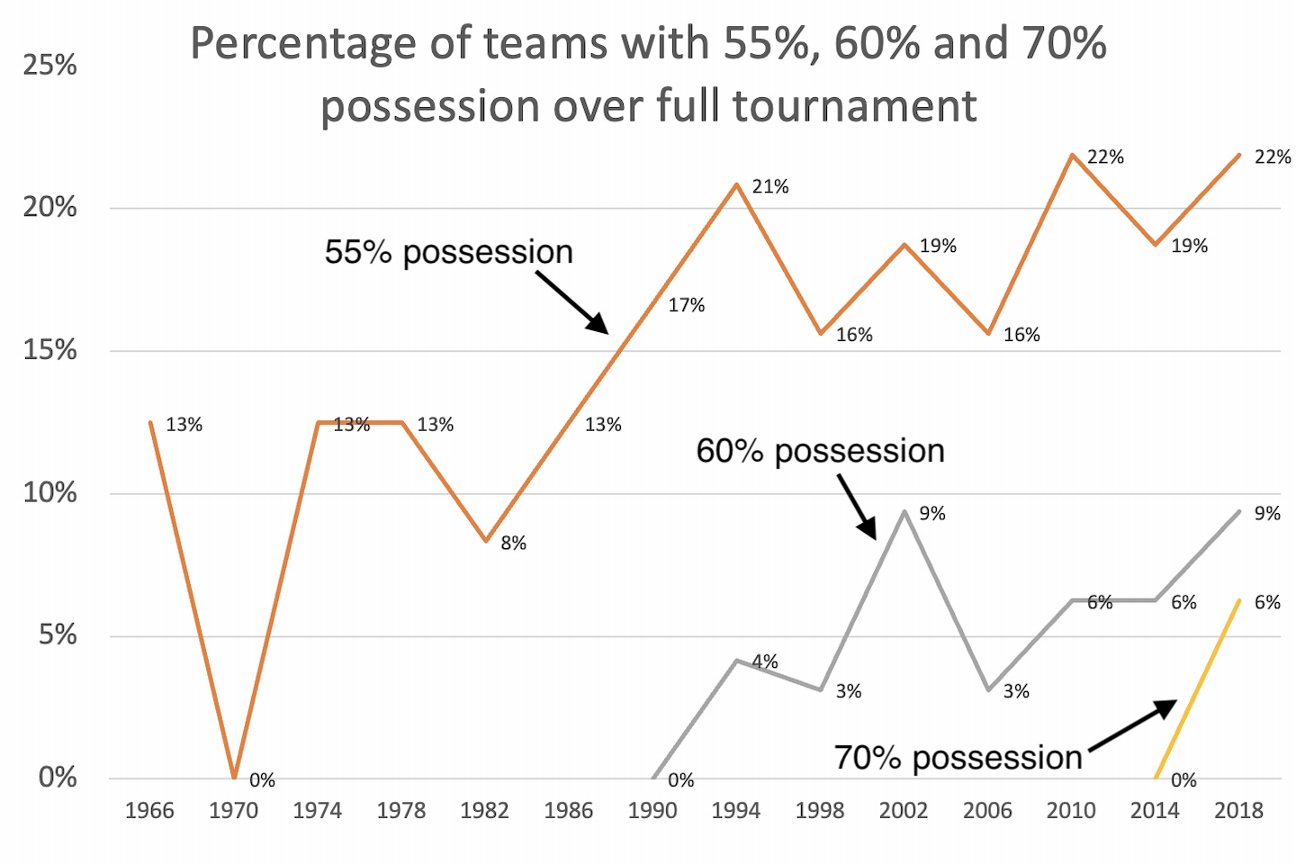

While passing averages rose and possession numbers fell in the 2010s, we didn't have to wait that long to see the rise of ball possession as a form of dominance. While typically only one or two teams would enjoy more than 55% possession over the course of a tournament in the early stages of this data range, that began to change in 1990 and never looked back.

Since 1990, at least 16% of World Cup teams enjoyed 55% possession or more; the 1994 tournament saw the first instance of a 60% team -- there's been at least one in every tournament since -- while Spain became the first 70% team in 2018. We often search for (and find) ways that club soccer or specific club teams have impacted the sport. If "possession as dominance" indeed rose in the early 1990s, is that an endorsement of sorts for Arrigo Sacchi's AC Milan teams of the time period? Sacchi and Milan were among the most famous early progenitors of a style that manipulated space and featured a high defensive line and heavy pressing.

Then again, this style didn't bleed over into Sacchi's own international experience. His 1994 Italy team reached the World Cup final, but boasted only 49.8% possession and 4.1 passes per possession. It was another star-crossed 1994 team, actually, that seemed like it was attempting to set the path for the future.

A team ahead of its time: 1994 Colombia

You probably know this story pretty well; there was a 30 for 30 about it, after all. A golden generation of Colombian stars came of age in the early-1990s; they entered the 1994 tournament as favorites and on paper, played like it. They dominated the ball to the tune of 65% possession (five percentage points higher than anyone else) and averaged 6.2 passes per possession (only two other teams were above even 5.0). We wouldn't see a team with such a modern stat line for a few more tournaments.

While bad luck is part of their story -- personified most directly by Andres Escobar's own goal against the U.S. -- it was even worse than you think. They opened the tournament with losses of 3-1 to Romania and 2-1 to the U.S. even though their xG differential in both matches was +0.4 (meaning, the shots they attempted were of higher value, and were more likely to result in goals, than those of both opponents). This pair of unfortunate and unlikely losses got them eliminated from the tournament even before their win over Switzerland. For the tournament, opponents attempted shots worth only 1.6 xG but turned that into five actual goals.

This Colombian team played at a level that should have won them the group, and in terms of the sort of influence World Cup success might have brought, they are one of the sport's great what-ifs.

Okay, so possession is great. But has anything changed from an actual scoring perspective?

Shot quantity has decreased, but shot quality has suddenly skyrocketed

The story basically goes like this: Over the 50 years or so since Total Football -- and with jolts provided by teams like Sacchi's Milan and the Spain/Barcelona duo of approximately 2009-2012, along with the growing influence of analytics -- soccer has slowly evolved into a sport with more passing, more focus on possession and an emphasis on taking fewer shots overall but more shots of a given quality (i.e. fewer long-range bombs). The possession trends seen above support that general vision to a degree; shooting trends do, too, although perhaps not quite as one would expect.

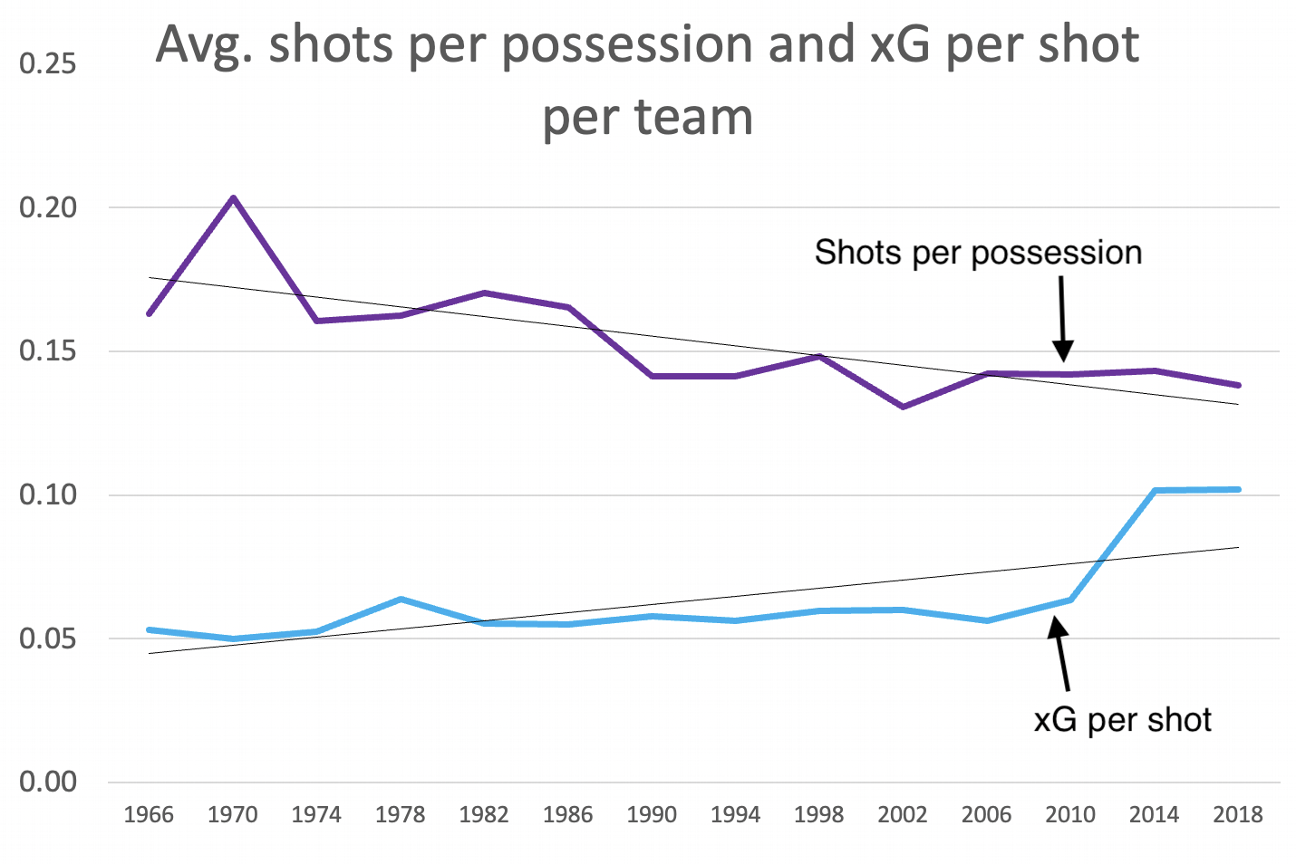

The 1970 tournament in Mexico saw eight of 16 teams average at least 0.2 shots per possession, including the champions (Brazil, at 0.27), runners-up (Italy, 0.26) and third-place finishers (West Germany, 0.25), plus a hyper Peru team (0.32!) that gave Brazil fits in the quarterfinals. For comparison, in the 2022-23 European club season, only four teams in Europe's Big Five leagues are averaging more than 0.2 -- Real Madrid, Manchester City, Bayern Munich and Napoli -- and none are higher than 0.22. There were lots of shot attempts.

The average trickled downward in the tournaments that followed, but seems to have found a cruising altitude: Every tournament since 1990 has averaged between 0.13 and 0.15 shots per possession per team. However, there hasn't been a corresponding rise in shot quality until very recently. Every tournament from 1996 to 2010 averaged between 0.05 and 0.06 xG per shot per team. That figure nearly doubled, to 0.10, in both 2014 and 2018.

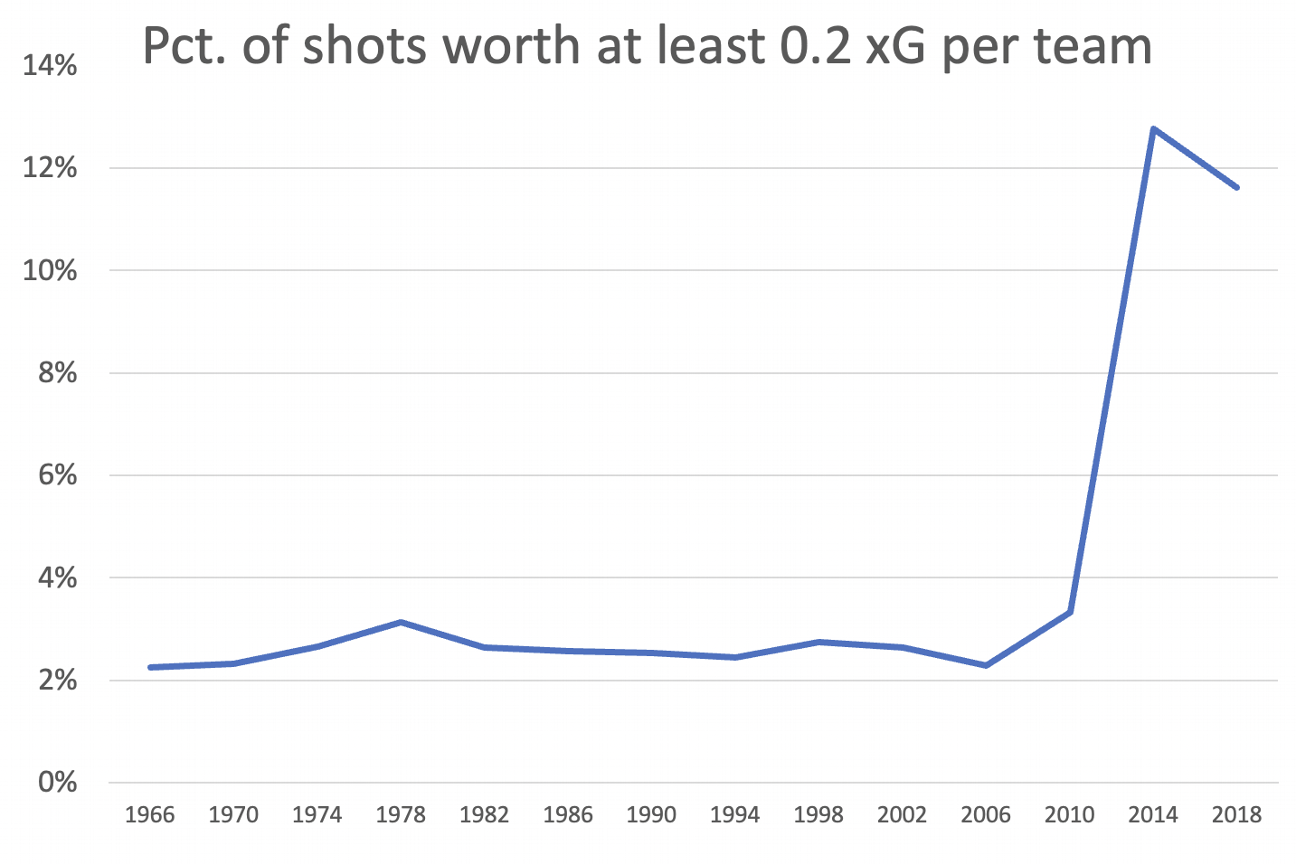

Here's an even more jarring look:

From 1966 to 2010, every tournament ended up with between 2.3% and 3.3% of shots being worth 0.2 xG or more. These shots are typically from closer range, as you would intuitively assume, and the importance of particularly high-value shots was illustrated clearly during Real Madrid's 2021-22 Champions League run.

My first thought when I saw the chart above was that there was a flaw of some sort in the data. Stats Perform has changed some of its data collection definitions and parameters through the years, and maybe the way xG is recorded also changed? Perhaps, but this lurch in shot quality is supported by other data.

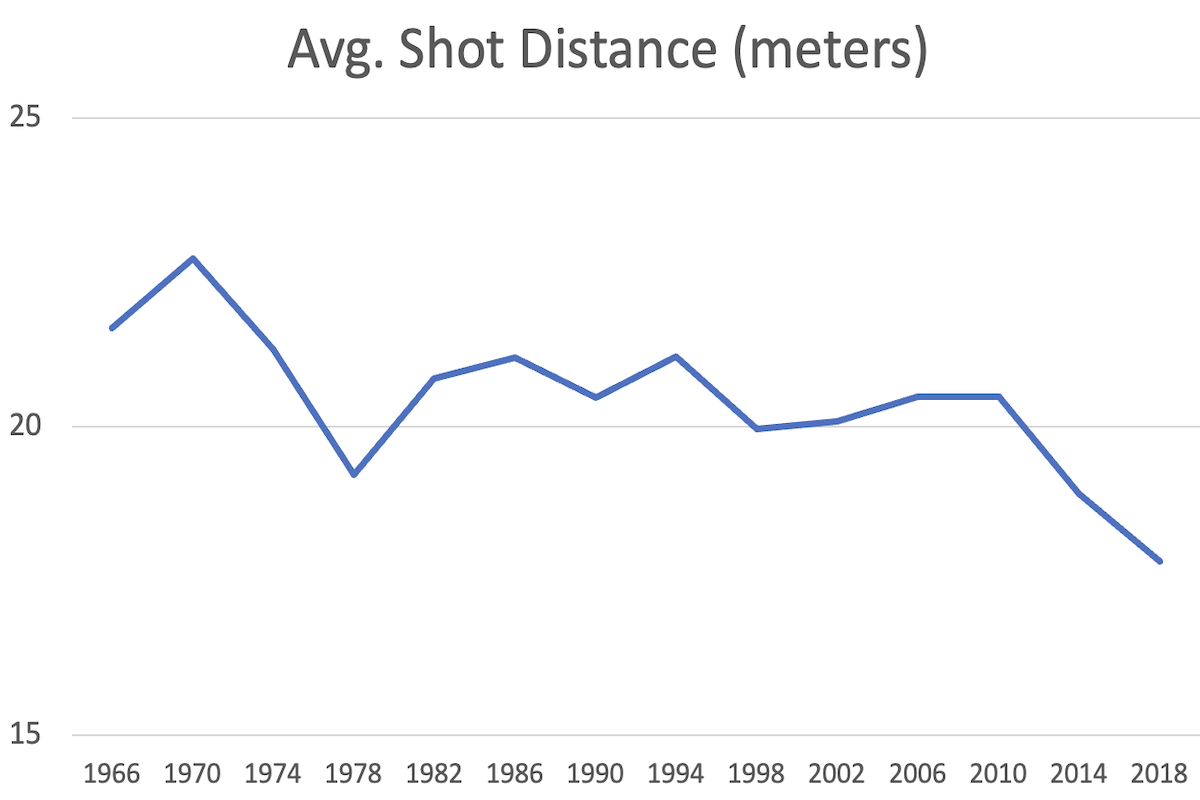

We should start with the simple fact that scoring increased by 20% from 2010 to 2014. But beyond that, average shot distance also fell by 8% in 2014 (from 20.5 meters to 18.9), then fell further in 2018 (to 17.8). In 2010, 16.8% of shots were taken within 10 meters of the goal; in 2014, that rose to 20.4%. That adds up quickly.

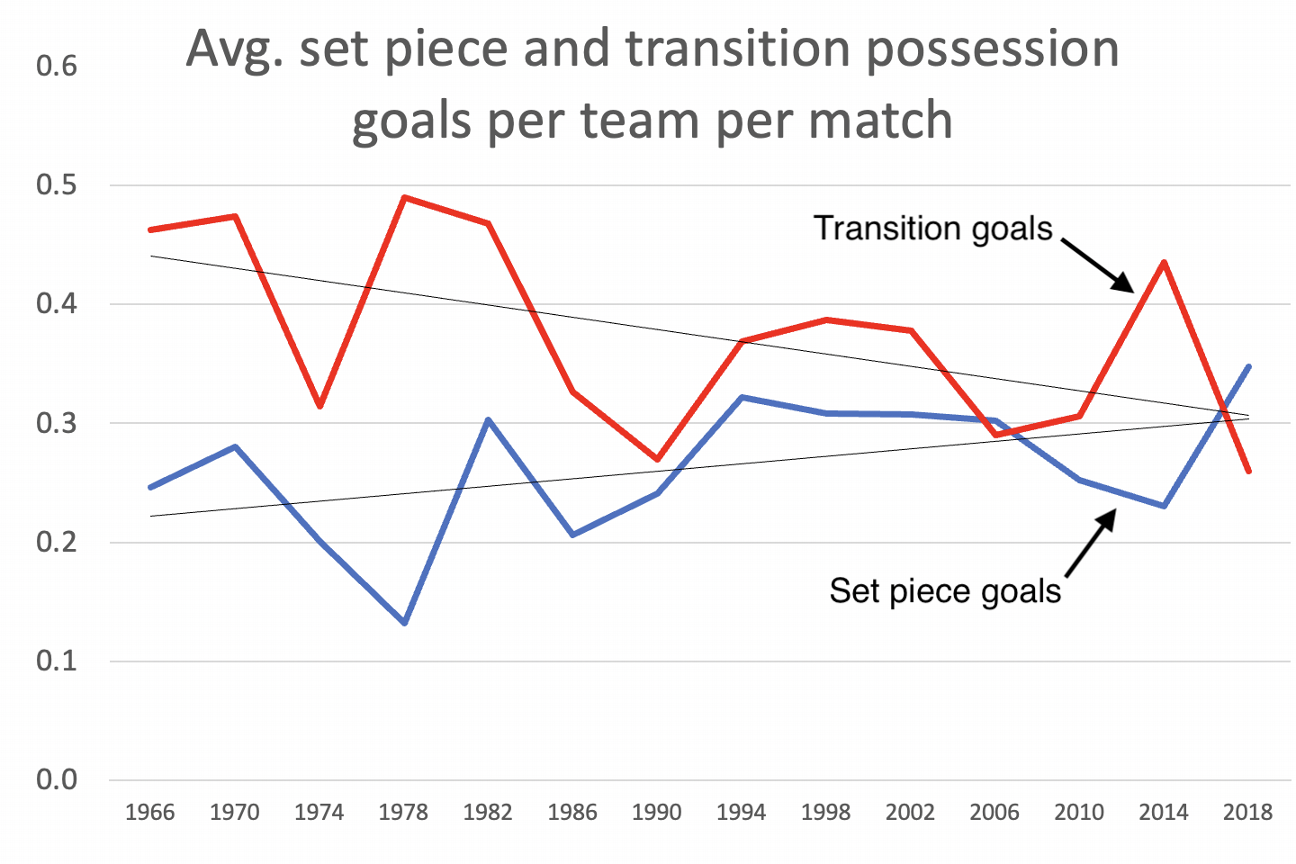

Teams undoubtedly began attempting far more high-quality shots in 2014, with the trend continuing through the 2018 World Cup. But the reasons for each tournament's prolific nature might differ. In 2014, we saw an explosion of goals from what I define as "transition possessions," or possessions that begin outside of the attacking third and last 20 or fewer seconds -- Belgium scored five of them in five matches, Netherlands six in seven, Nigeria three in four, Bosnia and Herzegovina three in three, etc. -- but that regressed significantly in 2018, just in time for set piece goals to explode instead.

Two things have made set piece goals more valuable: First, in 2014, teams began to get much better at corners. There were 15 total goals from corner kicks, and that total leaped to 25 in 2014, then 26 in 2018. But Stats Perform also logs penalties as set piece goals. And after teams won 15 pens in 2010 and 13 in 2014, there were 29 in 2018. That will also increase shot quality averages awfully quickly.

A team ahead of its time: 1974 Poland

As we see above, average shot quality barely budged for decades before this recent surge. But in 1974, Poland took loads of shots, took more good shots than most, dominated both in transition (6-0 scoring margin in transition possessions) and on set pieces (6-0 again) and came within a whisker of the tournament final.

Grzegorz Lato won the Golden Ball that year with seven goals, Andrzej Szarmach tied for second with five, and after winning a group that featured both 1978 winner Argentina (whom they beat 3-2) and 1970 finalist Italy (2-1), Poland beat Sweden and Yugoslavia in the second group stage before falling, like Morocco, via late goal to West Germany. They attempted 25 shots to West Germany's 11 but lost, 1-0, setting the stage for the Germans' upset of Netherlands. (They then outplayed Brazil in a 1-0 win in the third-place match. Tremendous team.)

The game has changed significantly in recent times

We can't say the results of this data dive have been incredibly surprising -- it confirmed what we've long known or suspected about the increased role of passing and possession and the sacrifice of shot quantity for shot quality. But seeing both how and when things changed is extremely worthwhile. The game slowed down a bit in the 1970s, then slowed to a crawl in the 1980s before finding a bit more balance between attacking, controlled possession and a lack of back-passes.

We also see that, for all the ways in which the game did or did not evolve from decade to decade, the impact of the turn-of-the-2010s "Spanish style" has been far more immense than anything else we've seen in this time period. Dominance via possession has increased by large amounts, and shot quality has exploded, even if in different ways for different tournaments. And in just a few more days, we'll get an opportunity to find out where this game has gone in the last four years and change.