The news jolted Dave Toub. Sitting at breakfast in March with Troy Vincent, the NFL's executive vice president of football operations, Toub heard the words he had feared for years.

"Troy said, 'You know, the kickoff is going to disappear,'" said Toub, the Kansas City Chiefs' special-teams coordinator. "He just stated it like that."

As they ate, Vincent told Toub about a competition-committee meeting a few days earlier. A data-driven video presentation from the NFL's medical staff had painted a bleak picture of the kickoff. Results of the inherent high-speed collisions were so jarring -- the kickoff is five times as likely to cause a concussion as other plays, members were told -- that Vincent ordered the video be stopped early. The endgame was clear.

"But when you start talking about how you may remove it," Vincent said, "now people are incentivized to devise solutions. Frankly, they have been outstanding."

And so began a two-month frenzy to reimagine the NFL kickoff in a way that would soothe owners who were spooked by the league's 2017 total of 291 concussions, the highest mark on record. Toub and eight other special-teams coaches proposed a set of rule changes and alignment adjustments that, while barely noticeable to most fans, should lower the frequency of concussion-causing collisions. Owners will review and likely approve the changes this week at their spring meeting in Atlanta.

Can it work? No one knows for sure. The kickoff will remain on "a short leash," according to Green Bay Packers president and CEO Mark Murphy, and will be evaluated annually for viability. In truth, no one can define quite yet what success might look like. Concussion numbers on kickoffs actually dropped by more than 20 percent from 2016 to 2017, according to league data. And even then, league executives scrambled to address them.

NFL competition-committee chairman Rich McKay said he would be "surprised if we don't make some progress on this play." But how much further must the numbers drop -- on top of last year's decline -- to ensure the kickoff's future?

"The only thing we can do is set up the parameters and see what happens at the end of the year with the numbers," Toub said. "Some injuries we need to live with. We're playing football. There are going to be things that happen. Sooner or later, we'll get to a point where [the NFL will say], we can live with that. I don't know what that point is."

A collection of tweaks

On their own, none of the proposed changes would have much impact. They are subtle enough, said retired NFL special-teams ace Steve Tasker, that most fans will see them and think the kickoff "is pretty much the same."

Together, though, the coaches believe their proposal will reduce speed before contact. They think it will force a phaseout of big linemen on the play and create an environment in which players are running with, rather than toward, each other.

Two initiatives took priority, according to Baltimore Ravens special-teams coordinator Jerry Rosburg. The first was to eliminate the two-man wedge, a rule that will also prevent teams from creating larger delayed wedges as the return develops. According to the proposal's wording, players would no longer align "shoulder to shoulder within two yards of each other and move forward together" to block. The wedge, according to McKay, accounted for nearly a third of all concussions on kickoffs over the past three seasons.

The second was to clean up the chaotic and uncertain moments prior to a touchback. The NFL has previously attempted to address kickoff safety by limiting returns via increased touchback incentives. As a result, nearly 60 percent of all kickoffs went for touchbacks in 2017. But the competition-committee video made clear that there are more than occasional injuries on touchbacks.

To bring that number down, the proposal calls for officials to signal an automatic touchback if the ball hits the ground in the end zone before it is touched by a member of the receiving team. In effect, the whistle will alert players earlier to the end of the play. In conjunction, Rosburg said he expects most teams to incorporate a version of the "iron cross" signal from returners, who would extend both arms horizontally as soon as they decide not to return the ball.

Coaches also have committed to providing players -- especially those who might have their back to the ball -- with more techniques for knowing when a touchback is imminent.

"You try to see the ball when it's kicked," Rosburg said, "and then open up, take a peek and run back. You'll have a pretty good indication of the direction and distance of the kick, and we're going to try to run with an awareness of where the ball is as we look back at our guy. ... Everyone is already doing some form of that, generally speaking. So it's not that big of a leap to do it better."

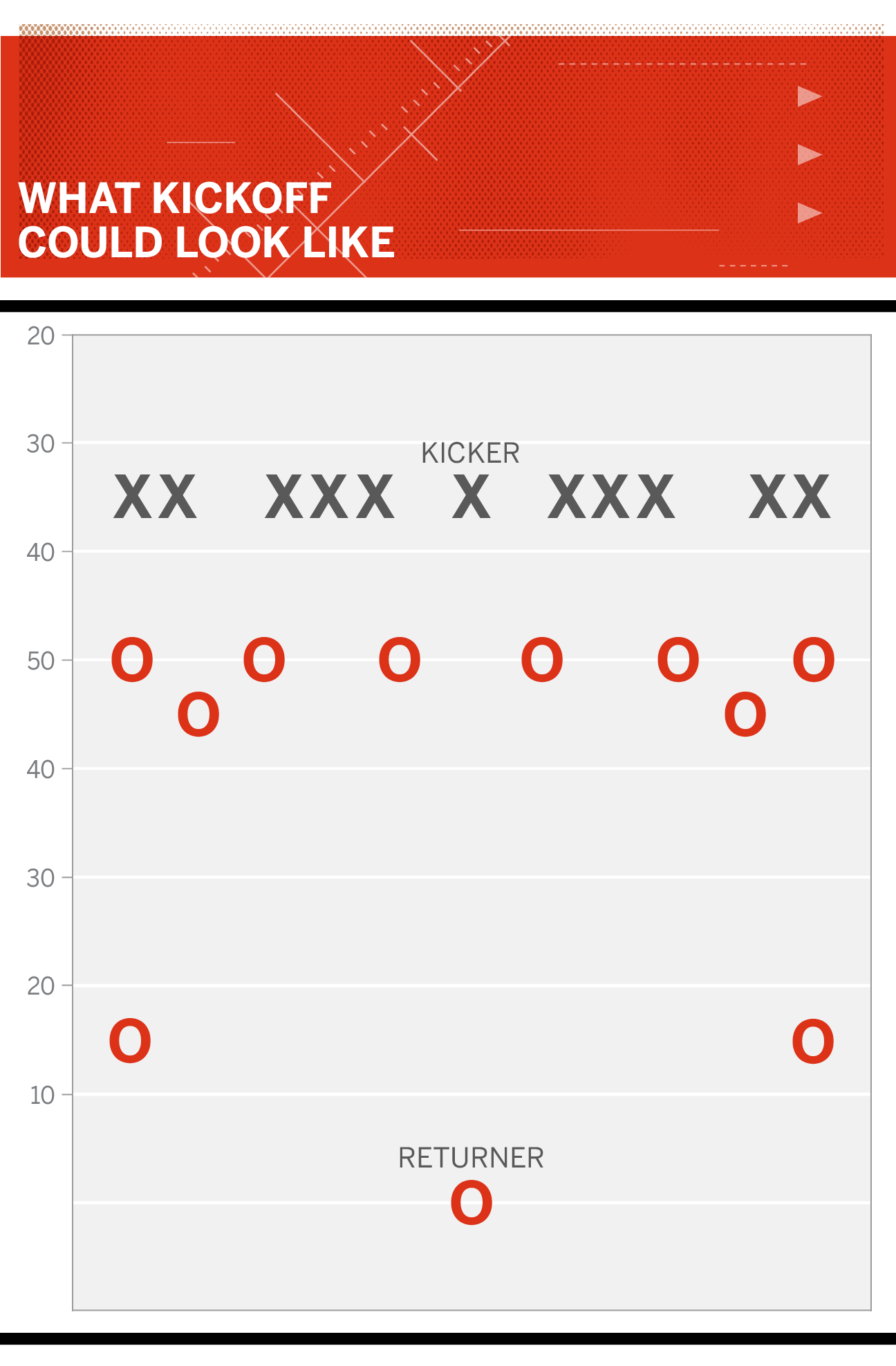

Meanwhile, the primary alignment shift requires eight men on the return team to be within 15 yards of the ball. That leaves only three in the back, including the returner. Practically speaking, the change eliminates the use of linemen on the return team. All three players in the back must be equipped to field the ball, and most coaches aren't likely to ask a 300-pound man to align in the front and then sprint to a spot 40 yards away to block.

"Some of the worst injuries that I've seen," Murphy said, "are maybe big-on-little -- larger linemen in the wedge hitting defensive backs."

Finally, a number of coaches said they will redouble awareness about players' responsibilities to each other. After watching a video compilation of injuries on kickoffs, Minnesota Vikings special-teams coordinator Mike Priefer said "cheap shots" should be counted among the culprits.

"We want talk about 'capture but don't kill,'" Priefer said. "You don't have to blow a guy up. Use your hands. Use your feet. Be an athlete. Don't try to be a tough guy. To me, this is not just about rules and proposals, but also how you teach and play the game, to be honest with you. That's part of making this a safer play."

Favoring the return?

Some of the adjustments appear certain to favor the return team, a not-unintentional consequence that evokes the NFL's effort to help quarterbacks and the passing game over the past two decades.

The kickoff-coverage team, for instance, will no longer get a 5-yard head start. Each player, other than the kicker, must line up within 1 yard of the restraining line. The restriction might sound minor, but Rosburg said that early testing has shown players reaching a "vastly different" spot downfield when they have a 5-yard head start than when they do not over the same time period. In effect, returners should have more distance between them and would-be tacklers under the new rule.

That space could discourage some teams from the recent surge of short kicks that are designed to force a return, possibly resulting in fewer touchbacks. And return teams could be more likely to take the ball out of the end zone given the increased strain on the coverage team.

New requirements for the cover team's alignment -- five men on each side of the kicker, with no pre-snap loops or twists -- should make it easier for return-team members to identify their assignments and execute blocks.

"In my humble opinion," Rosburg said, "I think we're going to see a higher percentage of returns than we've had. I also believe we're going to have a safer play. If we can accomplish both of those -- if we can get more returns with more exciting plays for our fans to watch, so they're not bored by touchbacks, and make it a safer play -- that's not just a home run. That's a grand slam."

Now or never?

Internal optimism aside, it's fair to step back and wonder if a collection of inside-football adjustments will be enough to satisfy owners and league executives who are concerned in equal measure about safety and the appearance of safety. NFL rule changes can take years to create the desired effect, often after annual tweaks. The kickoff probably doesn't have years to reach a reasonable safety threshold, and of all the positive reactions to the proposal, none has suggested it was bold.

Murphy said he is "cautiously optimistic" of achieving a safer play but made clear that the injury data meant "you've got to do something." McKay lauded the "buy-in" from coaches who seem to understand the existential threat. If the numbers don't drop quickly enough, Tasker thinks it impossible to "blow it up and start from scratch" rather than simply eliminate the kickoff.

But in reality, the kickoff is at the edge of a cliff. Rather than slowly test ideas in preseason games or in the Pro Bowl, as it usually does, the NFL has fast-tracked a proposal with equal parts optimism and desperation. It relied on special-teams experts, a decision that ensured sound suggestions while also providing cover should owners ultimately demand elimination. Has the kickoff been reborn? Or has its death simply been delayed? We'll soon find out.