As a University of Florida running back, Chris Rainey was named a suspect in five crimes in Gainesville. He faced charges once.

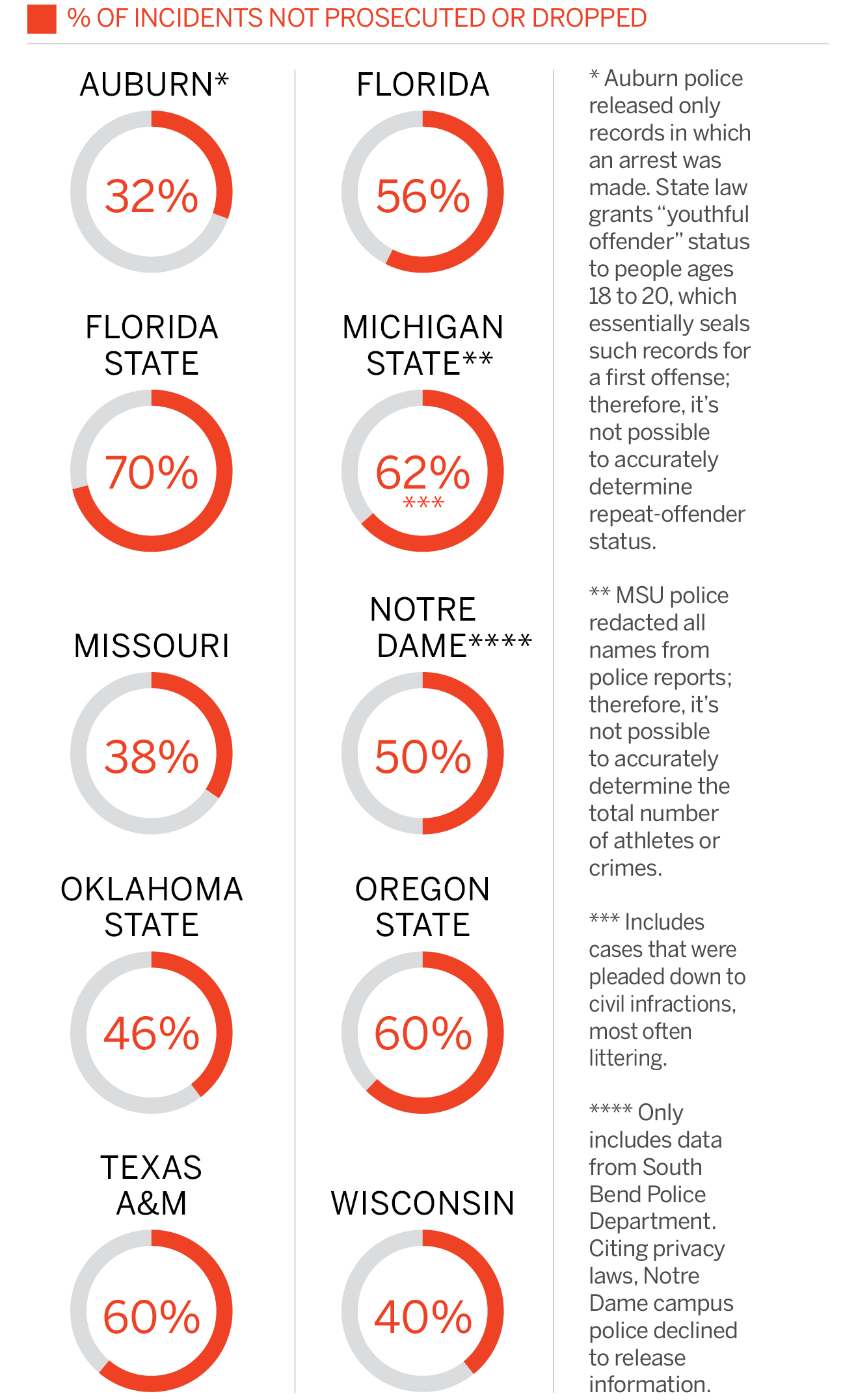

Rainey's experience as a star athlete accused of criminal activity -- stalking, fighting, injuring someone with fireworks -- but ending up with a mostly clean record is not uncommon: From 2009 to 2014, male basketball and football players at the University of Florida and Florida State University avoided criminal charges or prosecution on average two-thirds of the time when named as suspects in police documents, a result far exceeding that of nonathlete males in the same age range, an Outside the Lines investigation has found.

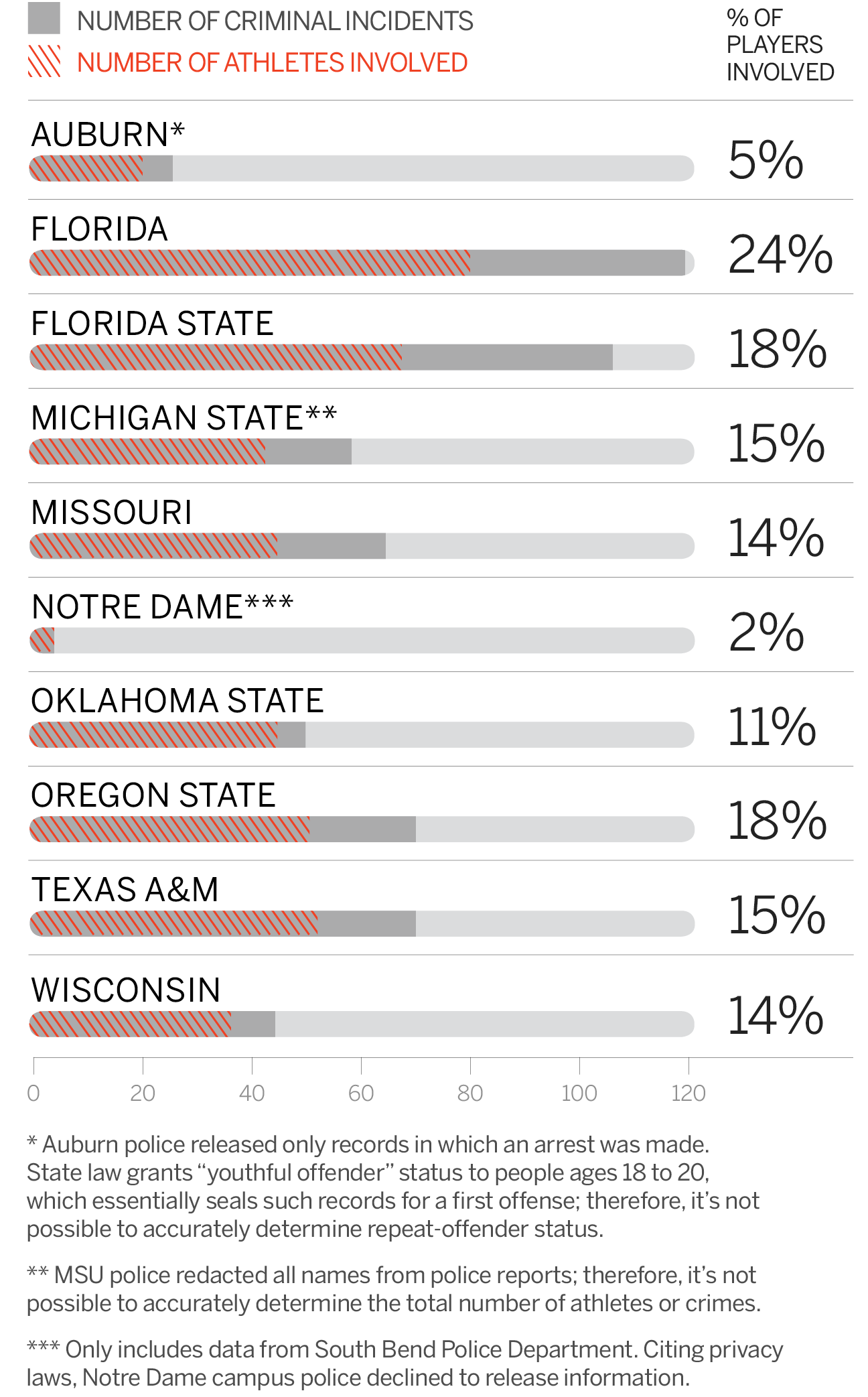

Last fall, to determine how often crimes involving college athletes are prosecuted and what factors influence them, Outside the Lines requested police reports involving all football and men's basketball players on rosters from 2009 to 2014 from campus and city police departments covering 10 major programs: Auburn, Florida, Florida State, Michigan State, Missouri, Notre Dame, Oklahoma State, Oregon State, Texas A&M and Wisconsin. Some police departments withheld records citing state disclosure laws. (ESPN sued the University of Notre Dame and Michigan State University for not releasing material; both cases are pending on appeal.) And not all information was uniform among jurisdictions.

But available reports showed that Rainey's alma mater, Florida, had the most athletes named as suspects -- 80 in more than 100 crimes at Florida. Yet the athletes never faced charges, had charges against them dropped or were not prosecuted 56 percent of the time. When Outside the Lines examined a comparison set of cases involving college-age males in Gainesville, 28 percent of the crimes ended either without a record of charges being filed or by charges eventually being dropped.

Florida State had the second-highest number of athletes named in criminal allegations: 66 men's basketball and football athletes. In 70 percent of those incidents, the athletes never faced charges, had charges against them dropped or were not prosecuted. By comparison, cases ended up without being prosecuted 50 percent of the time among a sample of crimes involving college-age males in Tallahassee.

Overall, the Outside the Lines investigation found that what occurs between high-profile college athletes and law enforcement is not as simple as the commonly held perception that police and prosecutors simply show preferential treatment, although that does occur. Rather, the examination of more than 2,000 documents shows that athletes from the 10 schools mainly benefited from the confluence of factors that can be reality at major sports programs: the near-immediate access to high-profile attorneys, the intimidation that is felt by witnesses who accuse athletes and the higher bar some criminal justice officials feel needs to be met in high-profile cases.

Other factors found from the examination of the 10 schools:

• Athletic department officials inserted themselves into investigations many times. Some tried to control when and where police talked with athletes; others insisted on being present during player interviews, alerted defense attorneys, conducted their own investigations before contacting police, or even, in one case, handled potential crime-scene evidence. Some police officials were torn about proper procedure -- unsure when to seek a coach's or athletic director's assistance when investigating crimes.

• Some athletic programs have, in effect, a team lawyer who showed up at a crime scene or jail or police department -- sometimes even before an athlete requested legal counsel. The lawyers, sometimes called by athletic department officials, were often successful in giving athletes an edge in evading prosecution -- from minor offenses to major crimes.

• The high profiles of the athletic programs and athletes had a chilling effect on whether cases were even brought to police and how they were investigated. Numerous cases never resulted in charges because accusers and witnesses were afraid to detail wrongdoing, feared harassment from fans and the media, or were pressured to drop charges in the interest of the sports programs.

'I conducted my own investigation'

On a Thursday morning in mid-December in 2010, just as the Oklahoma State men's basketball team was getting ready to practice, six police officers showed up at Gallagher-Iba Arena in Stillwater and approached coach Travis Ford. The officers had a search warrant and wanted to speak with some players, but especially Darrell Williams.

Williams was under investigation for rape and sexual battery.

He was in a film session, Ford told the officers -- they'd have to wait 10 minutes. So two officers waited, and 30 minutes later, Williams arrived. One of the officers wrote in a police report that Ford "was hesitant to do anything to assist us in locating the players and executing the warrants."

College athletes and crime

Outside the Lines studied how many football and men's basketball players from 2009-14 were suspects in criminal incidents.

A year and a half later, during Williams' criminal trial, testimony revealed that Ford had actually heard about the sexual assault allegations before being contacted by police -- through a letter the alleged victims sent to his office. After he received the letter, Ford had Williams and another player come to his house for a meeting to talk about the allegations. Ford said he never contacted police because the letter had indicated police had been notified.

"I conducted my own investigation," Ford testified in court.

His conclusion? Williams was innocent.

A jury in July 2012 found otherwise, convicting Williams of rape and sexual battery; however, the conviction was overturned on appeal last year when it was determined at least two jurors had made an unauthorized visit to the crime scene. Ford and an athletic department spokesman did not respond to requests for comment from Outside the Lines.

Former Assistant District Attorney Jill Ochs-Tontz deems the incident and what happened afterward wholly disturbing.

"By the time law enforcement got involved, Travis Ford [had] pulled the athletes in, talked to them and made sure their stories were straight," she said. "From the university's side, they moved immediately to protect these athletes and did not cooperate in the investigation."

In the Outside the Lines investigation, the Stillwater Police Department stood out because its officers are instructed not to notify school officials when an allegation involves an athlete, unlike many departments where it's common to give athletic departments or universities a heads-up: "It would give the appearance that there could be some special treatment," said department spokesman Capt. Kyle Gibbs. "We don't want to give anybody special treatment."

Police reports involving athletes at several schools show that city and campus police routinely notify campus administrators, coaches or athletic department officials when an athlete is involved in a crime. Some -- such as the University of Wisconsin campus police, University of Florida campus police and Corvallis (Oregon) police -- also had liaisons assigned to the athletic department or university officials.

It also works in reverse, with officials at some athletic programs -- including Florida, Florida State and Oregon State -- reaching out to police and prosecutors. And sometimes, they want more than just information.

In a Florida State University Police Department case from August 2012, officers asked a football player whether they could examine his car in connection with a possible hit-and-run, but he told them he was busy and would call back later. He did so but never reached an officer. Officers ultimately heard from FSU associate athletic director Monk Bonasorte, who asked whether he could bring the vehicle to the police station "due to [the player] being in a mandatory football meeting."

Bonasorte's name appears in multiple players' police reports. He also helps arrange legal representation for players accused of crimes.

After reviewing details of the alleged hit-and-run and Bonasorte's involvement, Florida State Police Chief David Perry told Outside the Lines "that's not how it always goes. ... I am not in support of anyone else trying to intervene" in an investigation. He added that sometimes, though, a coach or administrator can be helpful in getting an athlete to cooperate.

A former Florida State athletic department employee told Outside the Lines that Bonasorte's routine involvement in criminal cases troubled some colleagues because of the administrator's own record; Bonasorte, a former Florida State football standout, pleaded guilty in 1987 to charges of cocaine distribution and served six months in prison. Bonasorte, through a university spokeswoman, declined a request for an interview.

"He is kind of the fixer for football," the former staff member said. "He knows where the skeletons are buried, but he also helps keep those football players, not out of trouble, but out of paying for the trouble they've gotten into."

In Tallahassee, Outside the Lines found at least nine examples from 2009 to 2014 in which officers documented that Florida State coaches or athletic department officials tried to determine when and where city police would interview athletes or attempted other involvement.

"That would be a classic example of real poor police work," said Willie Meggs, the state of Florida's chief prosecuting attorney in the Tallahassee region. "You don't do an interview of a suspect -- football, non-football, athlete, nonathlete -- in their own comfortable environment. That's common sense."

A civil lawsuit filed this year against Florida State for how it addressed allegations of sexual assault against quarterback Jameis Winston includes an allegation that Bonasorte did not permit Tallahassee police detectives to contact two witnesses who were also football players until after Bonasorte had called attorneys for them.

Tallahassee police officials declined to be interviewed for this story but addressed specific questions about their practices with a statement via email that read in part: "If the investigators are unable to directly contact the involved party, they will then utilize intermediaries, including family, friends or attorneys to locate and conduct an interview with the involved party."

The exact opposite happened in 2010 at the University of Notre Dame, in one of the school's most notorious cases involving an allegation against a member of the football team.

Lizzy Seeberg, a student at neighboring St. Mary's College, told police that she had been sexually assaulted by a football player. But police didn't interview him until two weeks after Seeberg reported the incident -- and five days after Seeberg had committed suicide. Police initially indicated they couldn't find the athlete, according to Seeberg's father, Tom, even though there was a home football game just three days after the incident was reported.

That Tom Seeberg said police could not find the athlete on campus or at practice didn't surprise former Notre Dame police officer Pat Cottrell, who said a university policy prevented campus police from approaching athletes at any athletic facility. Further, the university would not allow anyone on the athletic staff to be contacted for help in finding a player, he said.

Cottrell, who worked 20 years for the department, said the policy took effect during Charlie Weis' coaching tenure, which began in 2005. Notre Dame officials did not respond to multiple messages left by Outside the Lines. Cottrell said he came across the policy only when dealing with athletes, although university officials have said in prior media reports that athletes did not receive special treatment.

Whether athletic department or university officials are aggressively involved or being potentially obstructive or both -- the actions can affect investigations, police reports show.

In October 2013, when Tallahassee police showed up at FSU basketball player Ian Miller's apartment to question him about a stolen vehicle, police wrote that "men's basketball coach, Coach [Leonard] Hamilton, requested to be with Ian during questioning by police. Ian's story slightly changed from his original story."

(Miller's brother would end up admitting to taking the vehicle, and he agreed to pay the victim for any damage; prosecutors declined to pursue charges. Miller was named as a suspect in three other crimes while at Florida State but never charged.)

Hamilton did not respond to requests for an interview. Miller, who is now playing professional basketball in Italy, answered questions via text message and wrote that coaches become involved because they "don't want any false things being said about their players."

"They wanted to make sure the cops handled the situation in orderly fashion," he wrote. "... Some coaches at other schools could care less about their players. They just use 'em. But at FSU, for all sports ... our coaches genuinely care and love their players and treat us as if we are their own kids and that's from scholarship players to walk on."

Police officers who support notifying coaches or college administrators say it prepares schools for the likely media onslaught that follows and can sometimes help get athletes to talk.

Officers in some departments refer certain incidents to coaches or school officials for punishment instead of pursuing criminal charges, especially for what the officers say are minor offenses or when evidence might fall short of prosecution. That's how Gainesville police handled Aaron Hernandez when the former Florida tight end admitted to drinking at a bar and hitting a bar manager when he was 17. Officers said they wouldn't charge him for underage drinking, "but that it would be noted in the report so the coaching staff may handle that issue internally."

According to the report, the bar manager told police he wanted to press charges for the alleged assault, but two weeks later told them that "he has been contacted by legal staff and coaches with UF and that they are working on an agreement" and "that he may request that charges be dropped." Public court records, which are limited in juvenile cases, show no resolution for that incident.

Expert legal help a phone call away

Hernandez's attorney was a man named Huntley Johnson, a graduate of Florida's law school, donor to its athletic fund and counsel to so many Florida athletes that a local newspaper even dubbed him the Gators' real MVP.

When Outside the Lines first presented Ben Tobias, spokesman for the Gainesville Police Department, with data showing athletes were less likely to be prosecuted than nonathletes, Tobias said the main reason was likely the athletes' unique access to legal counsel, which Outside the Lines found was a factor at such other schools as Florida State, Missouri and Oklahoma State.

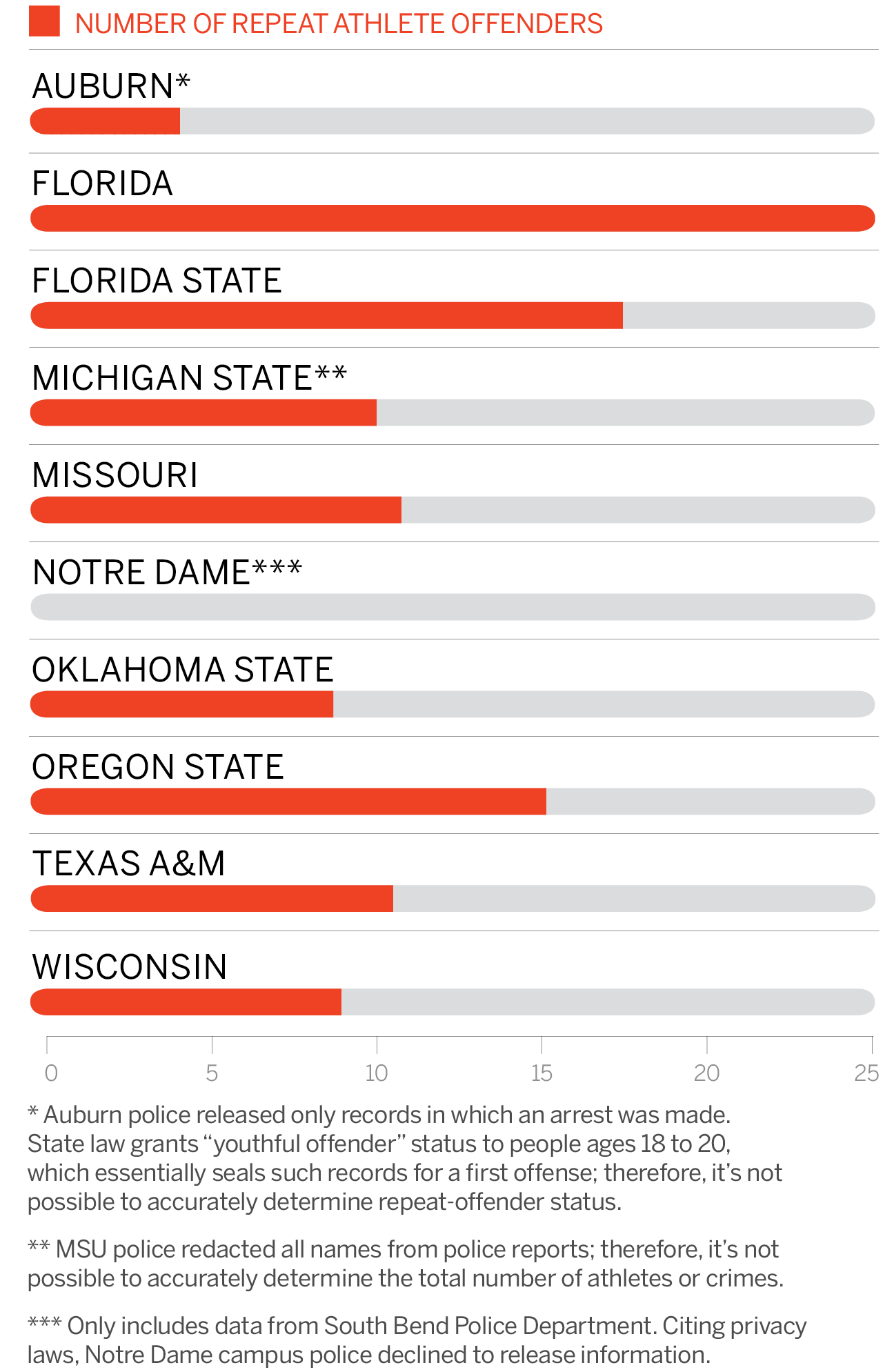

Repeat offenders

Among the football and men's basketball players studied by Outside the Lines, there were many repeat offenders.

"Sometimes we joke that [Huntley Johnson's] got a better communication system than 911," Tobias said.

Johnson, who has a history of rejecting media interview requests, declined to answer questions from Outside the Lines. The first time Chris Rainey -- the Florida running back with the long list of alleged crimes -- needed Johnson's help was September 2010, after Rainey sent his then girlfriend a text message that said, "Time to die, b----, U and UR!" while she was at home with her 8-year-old son and her sister.

Rainey was initially charged with felony stalking but agreed to deferred prosecution on a reduced charge of misdemeanor stalking.

Rainey told Outside the Lines that he remained wary of police but that he had confidence in Johnson to keep him, and the team, out of serious trouble: "... you still got Huntley, so, if anything happens, we got Huntley. So, he will get you out of anything, everything."

Even in the NFL, Rainey found himself accused in three additional crimes in Gainesville, including an arrest for dating violence and simple battery. He never faced any charges.

Tallahassee attorney Tim Jansen, who represented Florida State quarterback Jameis Winston against accusations of sexual assault more than two years ago, said there is a "90 percent better chance of getting a better outcome than a person who just does nothing, or they get a public defender, once they're charged."

The attorney, who charges some clients up to $500 an hour, said he gets paid by the families and does not represent them for free. He said he often gets alerted to cases by FSU's Monk Bonasorte, who has his personal cellphone number and will call him at the first sign of trouble.

"[Police] will contact probably Monk and say, 'We need to talk to this student,'" Jansen said. "Now, then my phone rings or somehow that magically does happen, and how it's done, I don't know. It's like making sausage."

In 2011, police reports show, Jansen showed up unannounced at the Tallahassee Police Department station as one officer interviewed a player suspected of striking and raping a prostitute. The allegations, although graphic, were inconsistent and coming from a woman who police said was coming down from a cocaine binge.

The player, who was not ultimately charged, had not called Jansen and was in the middle of detailing what happened when two other officers -- one of whom was a teammate's father -- interrupted to tell the athlete "he had representation in the lobby."

Tipped off to the trouble -- Jansen said it was likely by police -- Bonasorte called Jansen.

At the police department, Jansen spoke with the player for a few minutes outside of officers' presence, police reports show. The player returned and gave a different account of the night's events, admitting that he had sex with the woman but saying it was consensual.

Michigan State might prove an example of what happens when everyone is afforded the same legal counsel; students there can get a free defense attorney through the school's student legal services.

As a result, East Lansing Police spokesman Lt. Steve Gonzalez said, a lot of Michigan State students get attorneys for even the most minor cases, such as a ticket for having alcohol in public. And those same attorneys show up on athletes' misdemeanor cases.

When Outside the Lines analyzed the results of case dispositions involving Michigan State students compared with a set of East Lansing cases involving college-age males, there appeared to be no discrepancy like those seen at Florida State and Florida. About 62 percent of MSU athlete cases resulted in no record, dismissal or plea to a lesser charge of civil infraction; among the comparison set, it was 66 percent.

In felony cases, in which any defendant is likely to have an attorney, athletes sometimes still benefit by having better legal counsel than someone who has to settle for a public defender. That's what happened with Darrell Williams, the Oklahoma State basketball player who was initially convicted of rape and sexual battery after two women said he groped them and shoved his hands down their pants and penetrated them during a house party in December 2010.

Williams' attorneys were William Baker and Cheryl Ramsey, both known for representing Oklahoma State athletes and coaches. Ramsey is a veteran Oklahoma City criminal defense attorney who was part of the team selected to defend Oklahoma City federal building bomber Timothy McVeigh in the late '90s. She is currently defending former Oklahoma State football player Tyreek Hill, who was arrested Dec. 11 after allegedly choking and punching his girlfriend.

Ramsey said she took on Williams' case for free because of the severity of the charges and how they were out of character for him: "It wasn't that he was an athlete, but he was a person who needed help."

After a jury trial ended in a conviction in July 2012, Ramsey hired private investigators to interview jurors, which is how she found out that at least two of them had made unauthorized visits to the crime scene, which the Oklahoma Court of Criminal Appeals determined influenced the verdict; the appeals court overturned the conviction in April 2014.

Fear of involvement and fear of betrayal

Although several defense attorneys said in interviews that athletes were more likely than regular students to need an attorney because their status makes them prone to being targeted or falsely accused, Outside the Lines' examination found a significant number of examples to the contrary: Their fame deters victims and witnesses from coming forward.

When a woman told Columbia, Missouri, police in April 2014 that football player Dorial Green-Beckham had forced a door open and pushed her down the stairs in the apartment she shared with Green-Beckham's girlfriend, the girlfriend texted the alleged victim to persuade her to tell police to drop the charges.

"He will be kicked out of Mizzou and then not qualify for the [NFL] draft next year. The coaches talked to me and explained how serious this is and there's no time to waste at this point."

When police questioned the girlfriend about the texts and whether coaches had pressured her to get the charges dropped, she changed her story and said the coaches never talked to her directly but that Green-Beckham had told her to relay the information.

The alleged victim told police she wanted to drop the case: "She stated she was afraid of the media and community backlash since Green-Beckham is a football player," the report states. "[She] was afraid of being harassed and having her property damaged just because she was the victim. [She] stated she did not want to deal with the mental stress of the whole ordeal; it was already making her physically sick to think about it."

She had reason to be fearful. On TigerBoard.com, a popular online forum for Missouri fans, the name-calling and harassment had begun: "Which loser ass snitch called the cops over some drunk kids arguing?" "Snitches get stitches!" "No, just a jersey chaser looking for $." "Jock sniffin for dark meat team." "Is gold digging a sport?"

Incident resolutions

The incidents Outside the Lines examined did not always ended up prosecutions or charges.

Outside the Lines contacted Green-Beckham's agent, who declined comment and did not make Green-Beckham available for an interview. On May 1, Green-Beckham was drafted in the second round by the Tennessee Titans.

Outside the Lines found multiple examples of alleged victims and witnesses refusing to participate in criminal investigations -- including sexual assaults, fights and even theft -- because they were worried about publicity and fans harassing them. Others simply didn't want to get players in trouble.

Many of the alleged victims, mostly women, spoke to Outside the Lines on the condition their names not be revealed. They described fans who showed up at their workplaces to harass them; vulgar, sexual insults on the phone, in email and on social media; and even death threats toward them and their relatives.

Prosecutors routinely encounter reluctant victims and witnesses in everyday cases, especially domestic violence, but they say the element of celebrity and media coverage can take it to a higher level.

"I think it would be naive to suggest that the high level of publicly doesn't have a chilling effect on people," said Benton County (Oregon) District Attorney John Haroldson, whose office handles cases involving Oregon State athletes. "You certainly see that happen in cases of sexual assault ... they have to contend with, 'Do I want this to play out in the media?'"

Around midnight on April 12, 2014, Oregon State student Michael Davis said he and a friend had been arguing with some football players about cutting in line at a bar and he had fallen to the ground with one of them while fending off a punch. As Davis stood up, tight end Tyler Perry ran up and punched him in the head, knocking him to the ground, the police report states.

According to the report, Davis said a friend who played football told him that he "shouldn't call the cops. We won't have a starting lineup next year." Another person involved in the incident said he "knew the males to be OSU football players so did not really want them in any trouble."

Days after the incident, Davis said that one of his professors noticed several football players milling outside the door of a classroom and the professor told him to exit through a different door because she was afraid they were going to harass him.

"I never wanted to be that guy who turned on the football team," Davis told Outside the Lines, adding that he has several friends who were athletes.

Davis said he suffered $5,000 in injuries to his teeth and nose and has a scar that starts between his eyes and gives him sort of a "joker nose."

Perry, who did not respond to emails or phone messages left by Outside the Lines, admitted hitting Davis, according to the police report. Davis said he "was in disbelief" when the prosecuting attorney told him there wasn't enough evidence to file charges.

Two months later, Davis said, he ran into Perry at a party. Perry apologized, he said.

Although Davis said he appreciated Perry's apology, "all those guys got away with it, and I know it's not the first time it happened."

Madison (Wisconsin) Police Capt. Carl Gloede, whose district includes the University of Wisconsin campus, said he doesn't see many cases in which victims or witnesses are afraid to speak out against athletes in an investigation but said that might be in part because those cases don't get reported in the first place.

"If people have information and they're afraid to provide it because of the notoriety, we do our best to encourage that openness. But it's hard to provide anonymity to witnesses because the accused have the right to know who's accusing them of crimes," Gloede said.

State Attorney Willie Meggs in Tallahassee said he understands why victims would be unwilling to come forward, having felt some of the fan backlash himself when his office decided on the Jameis Winston case.

"I had people writing me saying that they hope my daughter and my wife got raped, and just all of those kinds of things for not doing this, and then I had people writing me saying, 'You're going to cost us a national championship, and you're just evil, and you hate athletes,'" he said.

When the Tallahassee Police Department took an unusual step of turning an ESPN public records request -- which contained the reporter's email address and cellphone number -- into a press release and posting it online on Christmas Eve, hundreds of Florida State fans responded to the reporter with harassing phone calls, emails, texts and social media posts, including many of a sexual and threatening nature. (Tallahassee police said the publication of the request followed departmental procedure, yet no other requests have been publicized in a similar fashion.)

One of the reports received from that request was an incident from July 2011, in which a woman reported that her ex-boyfriend, a Florida State basketball player, had broken into her apartment in Tallahassee. Police noted evidence of destruction and a voicemail suggesting the athlete had been there. The woman told police she simply wanted her ex-boyfriend to leave her alone and she did not want to pursue charges, the report states: "She has a great deal of concern that her name will end up in the news."

Gainesville's Officer Tobias said "everyone" is at fault for athletes having such leverage.

"It's the fault of the athletes, it's the fault of the victims, it's the fault of society, it's the fault of the media, because everyone paints this picture and holds athletes up on a pedestal sometimes and we all are making them invincible," he said. "The fans are making them invincible, and the victims themselves, they look up to them at the same time. So to think that they can be victimized by this person is sometimes a reach for them."

Producer Nicole Noren of ESPN's Enterprise/Investigative Unit, ESPN senior writers Elizabeth Merrill and Mark Schlabach, and freelance reporter Anna Hensel contributed to this report.