Few things in life make me happier than a well-crafted (American) football playbook. It lays out a coach's foundational principles and underlying philosophy. It defines how they intend to do the big things and, through the plays themselves, the small things too. Combing through one as a writer or fan, you are guaranteed to learn something about the sport you already think you know quite a bit about. (It's basically the entire reason I have a Scribd subscription -- sometimes, random playbooks show up there.)

Thanks to Andrea Pirlo, I now know that it works the same way for soccer. There aren't triple-digit-page playbooks, per se, but there are philosophical tomes all the same. Pirlo's master's thesis, submitted to the Italian FA as part of his Pro License courses, showed up online a couple of months ago. Translated from Italian to English, it is called The Football I Would Like.

- Stream ESPN FC Daily on ESPN+ (U.S. only)

- Make Bundesliga, Serie A picks for a chance to win an ESPN+ subscription!

- ESPN+ viewer's guide: Bundesliga, Serie A, MLS, FA Cup and more

Its existence is both fascinating, in that it allows us to see the game through a particularly thoughtful, expert set of eyes, and instructive, in that it allows us to compare what the Juventus manager desires to what his team is actually producing. (Oh, and they host Torino in the derby this Saturday -- stream LIVE, noon ET, ESPN+ (U.S.) -- which will give us another chance to see his work in action.)

(Note: any quotes below are translated from Italian and might not be 100% precise.)

First things first: how are Juve doing?

They're doing... okay. Not terrible, but most certainly not great, especially by the standards of a nine-time defending league champion.

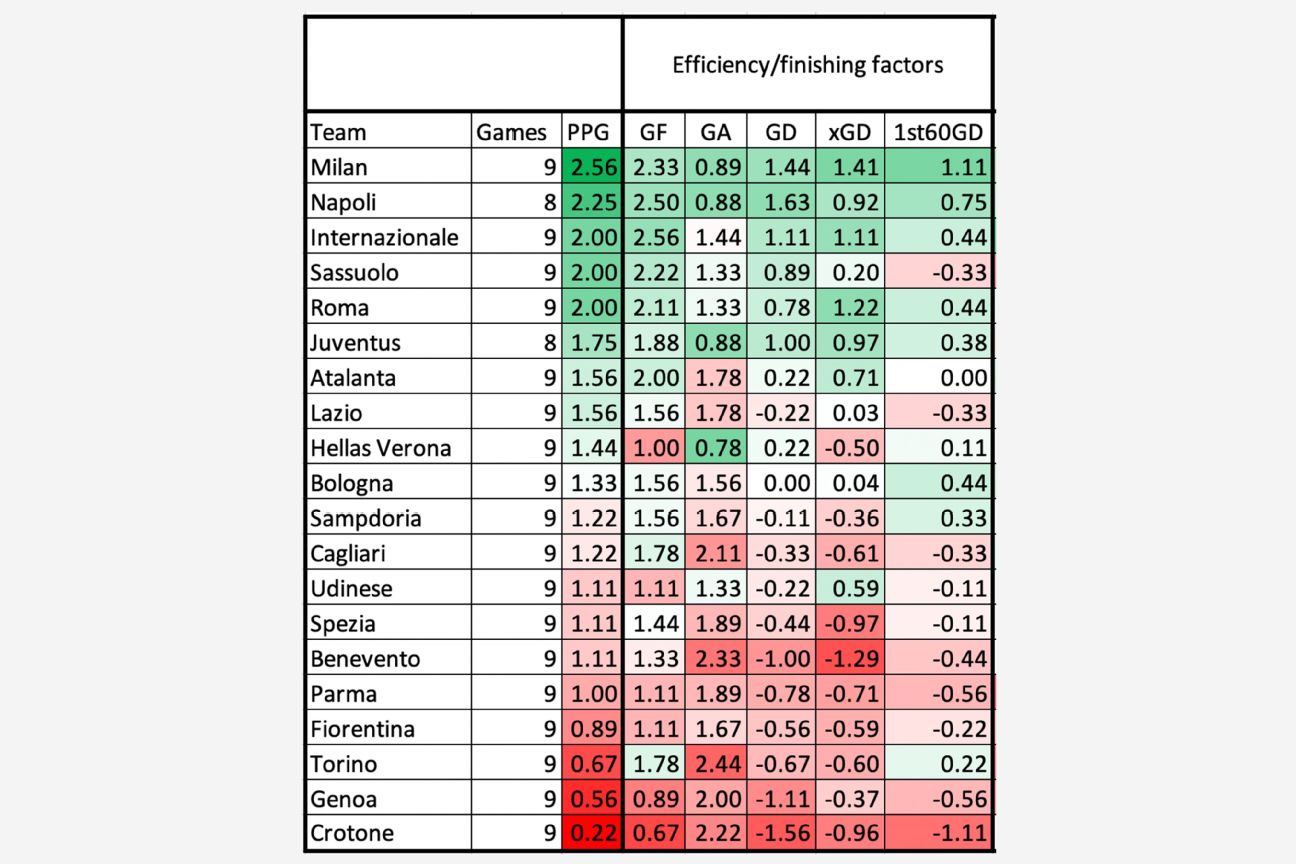

Not including their default win over Napoli, Juve are averaging just 1.75 points per actual game played, which would project to just 67 points over 38 matches. Teams with between 65 and 69 points finish around fourth place on average, and only one Serie A champion has had under 70 points in this century: Lazio, 2000-01. They are allowing the second-fewest goals per match, but they're averaging only the seventh-most goals. Their goal and xG differentials each rank fourth.

Juve haven't actually lost yet, but they're not closing out games, either: They've won three matches by a combined 9-1, scored three points via Napoli default and otherwise drew in five matches. They have, more than any big club in Europe, thrived in close-game situations through the years, but they are leaking points left and right early in 2020-21.

The good news? Nothing is blatantly or definitively broken. They're one point out of second place, and only six behind a torrid AC Milan. They're taking more shots and better shots than their opponents, they're finishing more of their possessions in the attacking third, and their average of one point per game in close games will almost certainly tick upward. They've qualified easily for the knockout rounds in the Champions League, too, albeit via a painfully easy group.

Still, they haven't yet played either Milan club -- they are away to both in January -- and... this is Juventus! I Bianconeri! You're not supposed to be rationalizing how it's not that bad for Juventus to be a few points out of first place. That alone makes Pirlo's first season disappointing thus far.

That said, alignment with Pirlo's professed vision would probably mean good things moving forward. So how is that going?

A modern football team playing a modern possession game

Heading into any sort of job interview situation, it's good to know the key words -- the things that the hiring manager probably wants to hear. For just about any of the 10-12 richest soccer clubs in the world, they probably want to hear about dominating possession. That's the name of the game in 2020, and Pirlo hit as many of those notes as he possibly could in his thesis.

- "I believe that a proactive, attacking and quality football can give great advantages."

- "The two key principles of my idea of football are linked to the ball: we want and must keep it as long as possible until we attack and we must have a strong competitive ferocity to go and recover it immediately once lost."

- "We want to attack well, to defend well."

Pirlo mentioned Pep Guardiola's Barcelona as one of the teams that has shaped his vision of what football can be. The quotes above went straight from Guardiola's brain to Pirlo's fingertips.

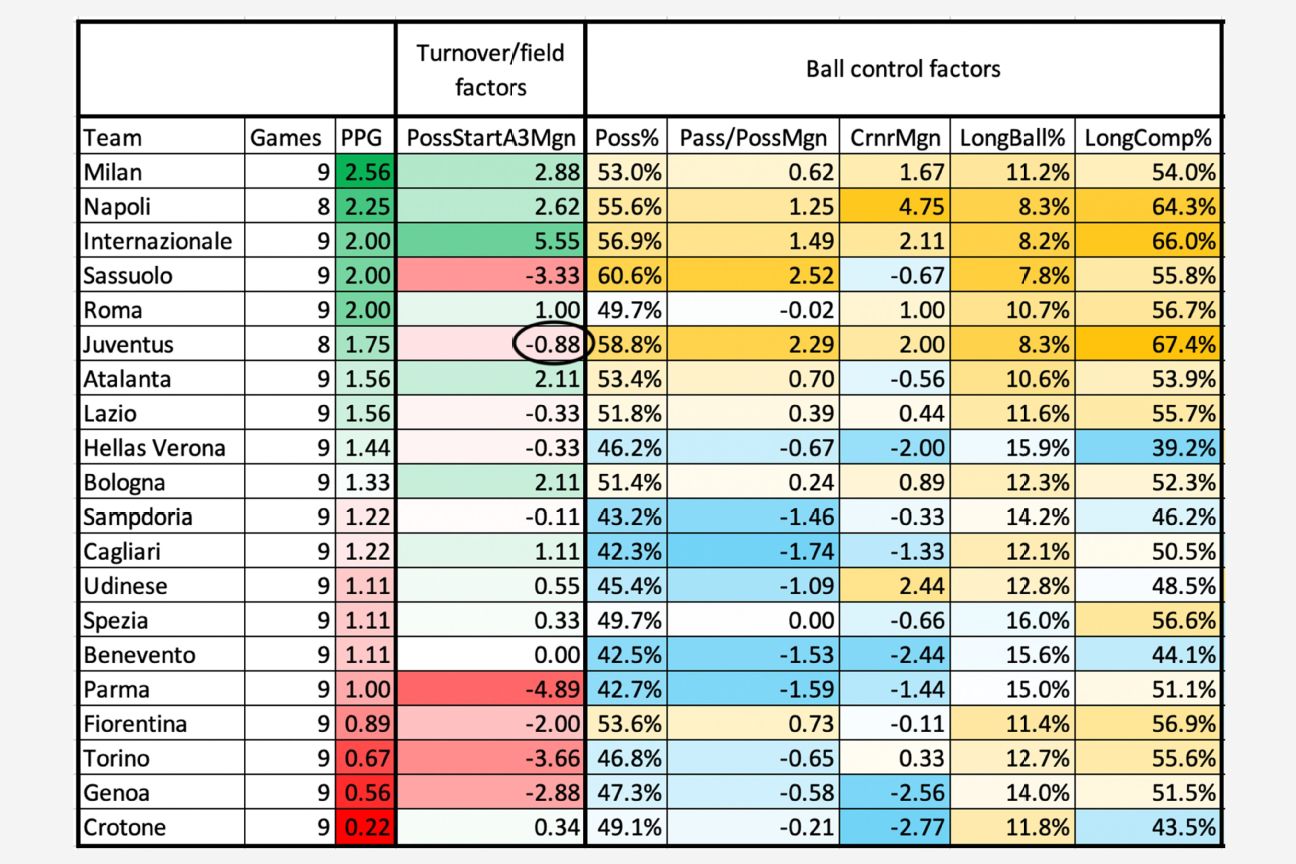

Pirlo wants to dominate the ball like a big club is supposed to, though Juve are only sort of doing that so far. Among Europe's big five leagues, 14 teams can top Juve's 58.8% possession rate; within Serie A, they rank second behind Sassuolo (60.6%) and slightly ahead of both Inter Milan (56.9%) and Napoli (55.6%).

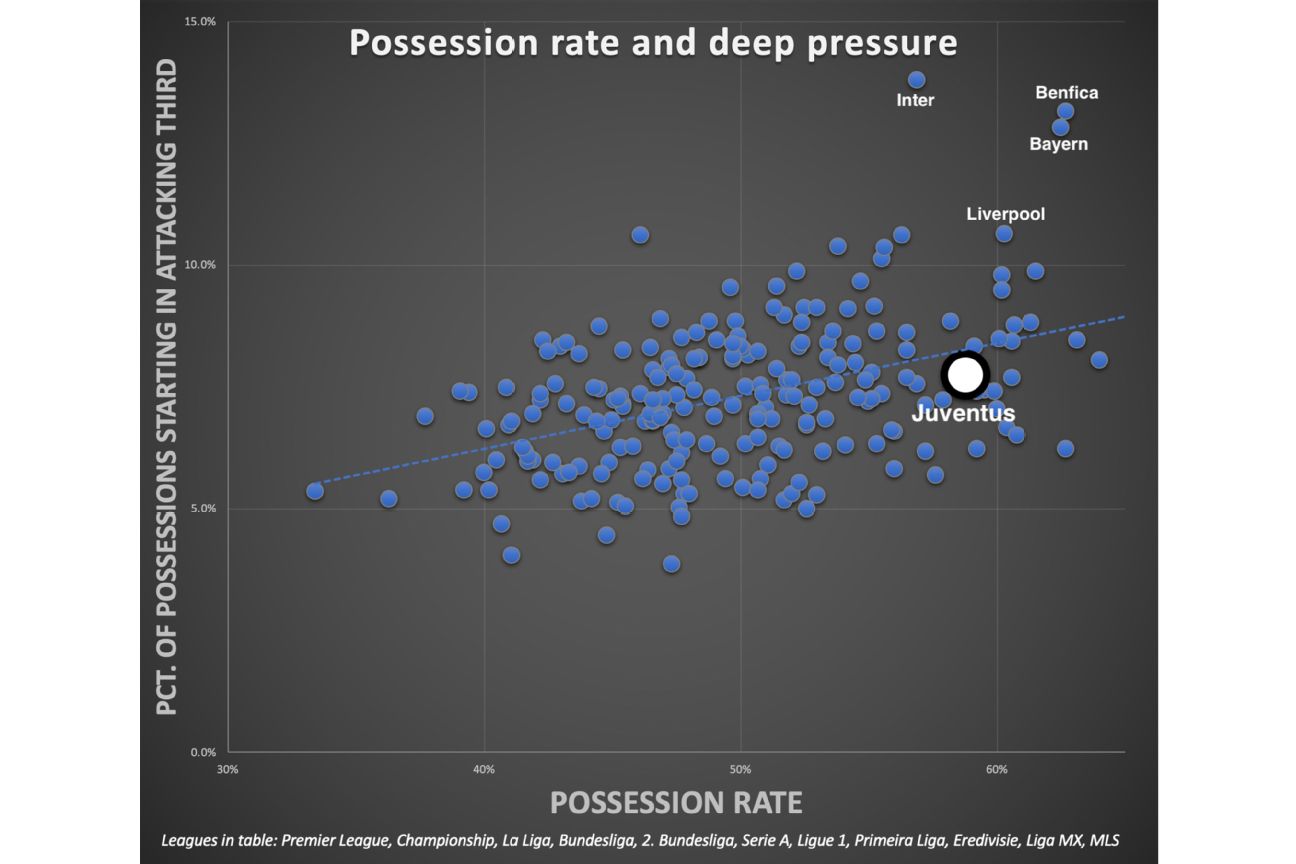

Of course, there's possession, and there's dangerous possession, often derived from the "go and recover it immediately once lost" portion of the quotes above. Juve are starting just 6.5 possessions per match in the attacking third, tied for 62nd among the 98 "Big 5" teams. They're still creating decent chances -- 47% of their possessions are ending in the attacking third (third in Serie A), and they're averaging 0.18 shots per possession (fifth) -- but they aren't creating enough pressure deep in their opponent's side of the pitch.

This is illustrated pretty well by looking at a wide swath of leagues.

In many ways, this is the Ronaldo Effect in action.

Twenty-one players in the "Big 5" have scored at least seven goals so far this year and between them, they've averaged 18.5 ball recoveries to date. But 35-year-old Cristiano Ronaldo has only seven, tied for the fewest with Milan's 39-year-old Zlatan Ibrahimovic.

Ronaldo is a one-man offensive structure; in three league matches without him, Juve have averaged just 1 goal per match and 0.10 xG per shot. In five with him, they're averaging 2.4 goals and 0.16 xG per shot. At the same time, they're starting 8.3 possessions per match in the attacking third without him and 5.4 with him. He creates his team's style of play no matter what the manager intends.

Saturday's disappointing 1-1 draw with Benevento, played without Ronaldo, was the clearest possible case study. With Alvaro Morata, potential Ronaldo successor Federico Chiesa and the slumping Paolo Dybala starting up front, Juve enjoyed 63.1% possession, started 12 possessions in the attacking third and doubled Benevento's shot total. But they averaged just 0.10 xG per shot, Dybala missed one the few high-quality attempts wide, and Juve couldn't pull ahead.

A different kind of "key pass" (and a Juve strength)

From Pirlo's (translated) thesis: "In the possession phase, the defenders became the first directors of the team, often taking the task of setting up given the numerous man-made scoring to which the play teams are subjected. By now the 'key passes' (ball transmission that crosses an opposing pressure line) of the central defenders are numerically reaching those of the central midfielders, who have always been leaders in this important statistic."

The idea of breaking a line of pressure isn't something we discuss too much statistically, and big data platforms already have a stat called "key passes," which measures something completely different.

Whatever we want to call it, though, we can rather effectively measure the concept of level-to-level passing by simply looking at the completion rate of passes from the defending third of the field (D3) into the middle third (M3). As it turns out, this is a particular Juve strength.

Pass completion rate, forward passes into the middle third by players other than the goalkeeper (Big 5 leagues):

1. PSG (81.0% in 24.5 passes per game)

2. Real Madrid (77.4% in 27.0)

3. Juventus (74.3% in 28.8)

4. Barcelona (73.5% in 20.6)

5. Sassuolo (73.0% in 28.8)

6. Napoli (73.0% in 24.5)

7. Borussia Dortmund (72.1% in 28.7)

8. Monaco (71.9% in 24.3)

9. Rennes (71.8% in 31.9)

10. Angers SCO (70.7% in 31.3)

Juve are among the best in Europe in safely transporting the ball from one zone to another, though that didn't begin with Pirlo. After completing just 66.7% of these passes in 2018-19, they improved to 74.9% last year under Maurizio Sarri. They're hitting basically the same mark this time around. Last season, Leonardo Bonucci and Alex Sandro completed 75% of 341 such passes; this year, with Sandro sidelined by a hamstring injury, Bonucci and left-back Danilo have completed 78.7% of 89 passes so far.

Quality in this regard has allowed Juve to organize solid attacks without high-quality pressing, but it hasn't stopped opponents from creating chances from pressure themselves. Opponents have begun 7.4 possessions per match in the attacking third, more than Juve. It's a glitch in the ball-control matrix.

On the bright side, Sassuolo, another good "D3-to-M3" team, struggles even more in this regard. Structure has potential downside.

What's a midfielder's role? Everything.

While roles in soccer have morphed and grown more all-encompassing through the years -- through their pressing, attackers are the front line in defense while, as Pirlo notes above, central defenders are often the catalysts for proper offensive buildup. We can still come up with a pretty well-defined set of primary duties for central defenders, strikers, wingers and so on, but a midfielder's role has never been more comprehensive.

Again, from the Pirlo thesis:

"After a historical period dominated by physical midfielders (1990's), the effectiveness of technical players with great vision of the game in the middle of the field has been rediscovered. Obviously, to these qualities, a good dose of mobility must be added to be able to perform more functions (construction and finishing, for example) and an especially mental predisposition to the defensive phase, with immediate re-attack in case of loss of the ball."

According to Pirlo, the midfield as a collective is the key to pressing ("the midfielders [are] most involved in the re-aggression phase"), defensive solidity in the box (he "enters the defensive line to compose a fundamental 5-a-side line, to better defend in width and be aggressive centrally") and speedy attacking transitions ("having midfielders, winger and forwards of the leg allows you to be able to restart quickly in attack"). A good midfielder must be technically excellent, fast and strong. He must have great defensive instincts. And great offensive instincts. And pretty much every other trait in existence.

Sounds easy!

In turn, this creates interesting context for the moves Juventus has made since hiring Pirlo. With this lengthy list of responsibilities, you could easily make the case that stability in this area of the field might matter more than in others. Except Juve hasn't had much of that. They had already arranged to bring in Barcelona's Arthur (in basically a one-for-one trade for Miralem Pjanic) before Pirlo's hire, but they also signed 22-year-old Weston McKennie from Schalke and 22-year-old Federico Chiesa from Fiorentina, plus they brought 20-year-old Dejan Kulusevski back from a Parma loan and installed him in the lineup.

The promise and potential is obvious. Arthur is particularly solid in advancing the ball into attacking positions -- he's completing 89% of his passes into the attacking third, and he's winning 60% of his duels in the middle third. Meanwhile, the three leaders in Stats Perform's expected assists measure (xA) are Chiesa (1.2), McKennie (0.9) and Kulusevski (0.7). And neither Chiesa nor McKennie have topped 250 league minutes yet!

Still, injuries and positive COVID-19 tests have created a decent amount of instability in the lineup, and of the eight midfielders to have played at least 200 minutes thus far, four are new to the team and five are 23 or younger. This was all but guaranteed to create the type of inconsistency that Juve are suffering from this season.

Juve's roster desperately needed youth, and you could easily say they've still got a bit further to go in terms of freshening things up. But when you do that, you risk uncertainty, especially when you're doing it in what is evidently the most important area of the lineup.

The road ahead

This was always going to be a particularly challenging season for Juve and its title streak. The roster was aging and in need of refreshing; the club let mainstays Gonzalo Higuain and Blaise Matuidi leave for Inter Miami, traded Pjanic for the younger Arthur and even loaned out 30-year-old Douglas Costa to Bayern. They brought in 27-year-old Alvaro Morata to both complement and spell Ronaldo, and the four new midfielders mentioned above (including Kulusevski) have an average age of 21.8.

Executing a refresh without a hiccup or two is all but impossible; even Bayern stumbled a bit in Champions League play, if not in the Bundesliga, as they're going through a roster renovation of their own. Combine this with the fact that both Inter and AC Milan got their respective acts together in recent months, plus Napoli and Roma looked primed to improve, and we were all but guaranteed to see a race tighter than the ones we saw for most of the 2010s. So far, that's what is played out.

Juve has basically established a fourth-place pace this year, and there's nothing saying they'll ever find fifth gear. Honestly, I would probably bet against it. But if they perform well in key upcoming matches -- vs. Atalanta on Dec. 16, at Milan on Jan. 6, at Inter on Jan. 17 and, of course, the Champions League round of 16 in February -- they could buy themselves enough time to further fulfill Pirlo's vision, fully transform into the very model of a modern major football club and play for all the trophies they've grown accustomed to playing for late in the season.