Early in the 2009-10 season, Phoenix Suns big man Amar'e Stoudemire, goggles atop his forehead, ambled his way to the timeout huddle. The Suns, two years removed from Mike D'Antoni's tenure as head coach, were still burning up the floor at their usual breakneck pace. On this night, in this moment, Stoudemire caught his breath after a particularly frenetic sequence of possessions.

"Coach, am I a decoy or what?" he said to Alvin Gentry. "Because if all I'm going to do is sprint the floor like Carl f---ing Lewis, y'all need to get me some of those little track shorts to wear."

"Amar'e, relax," Gentry said. "You'll get yours."

Stoudemire occasionally voiced his frustration with being asked to dash up and down the floor at warp speed, yet going unrewarded for services rendered during significant stretches of the game. But by and large, he had been remarkably agreeable during his seven-plus seasons in Phoenix, the last six on teams ranked no lower than fourth in possessions per game. Mostly, it was service with a smile -- commendable because it was a lot to ask an NBA big man to do.

"We would run so much," Stoudemire says. "We had a tempo. I found myself up and down the court seven, eight times without touching the ball. But we were so dynamic at every position to where everyone was getting a chance to eat."

For about 20 years prior, the general job description for an NBA power forward or center was to mosey up the court and head to the block as his point guard gradually got the offense into its half-court possession. Sometimes, the big man would stick his paw in the air and call for an entry pass, then go to work in the post where, more times than not, he'd get an opportunity to shoot. Occasionally, he would be asked to set a pick on the perimeter or maybe a flex screen for a teammate cutting off the wing.

But it had become clear to Stoudemire a few weeks prior to the 2004-05 season that the old blueprint was obsolete. Phoenix had just acquired Steve Nash, and the point guard was eager to hit the Suns' practice court with his new teammates.

"Pretty much the whole team would be there playing pickup basketball before our season for the better part of a month," says Nash. "You could see the pace. You could see I was the new element to it that just wanted to push the ball down people's throat and create openings. My teammates -- and we had guys like Amar'e Stoudemire and Shawn Marion, Joe Johnson, Quentin Richardson -- were just salivating and were the perfect receivers in this spread offense, so to speak."

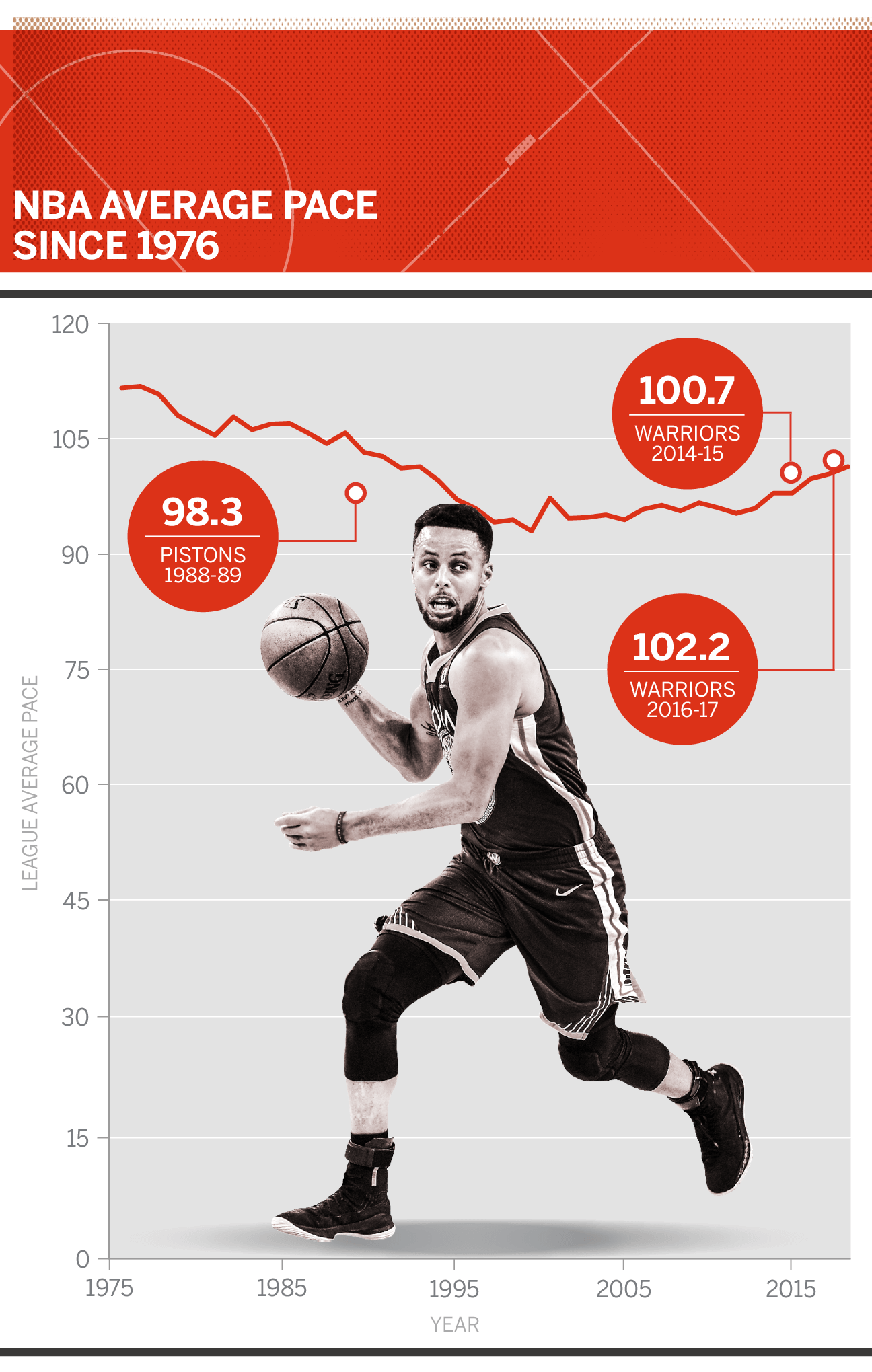

The Suns averaged 98.6 possessions per game that season, most in the league en route to 62 wins in D'Antoni's first full season as coach. Although the league as a whole was still playing slower than it had five years earlier, the Suns were the forerunners of a revolution. The NBA had received a jump start that would propel it into a new golden age, a better age -- one in which speed is a virtue and a pull-up 3-pointer in transition sends fans into mass hysteria. Nearly 14 years after those pickup games in Phoenix, the Western Conference finals between the Golden State Warriors and Houston Rockets are a formal celebration of the fact that what was once merely an idea has become the NBA's new normal.

Today, the Suns' "Seven Seconds or Less" offense of 2004-05 would be unexceptional when measured by possessions per 48 minutes. Back then, Phoenix's 98.6 pace was more than a possession per game faster than that of any other NBA team. In 2017-18, the average team had 99.6 possessions per 48 minutes, and the Suns' 2004-05 pace would have ranked 19th in the league.

In the intervening seasons, a league that toiled at a snail's pace for the better part of a decade from the mid-'90s onward has systematically adopted a frenzied, rapid-fire style of basketball. That uptick in pace has coincided with crowd-pleasing barrages of 3-pointers and attacks that exist as much in transition or "early offense" as they do in plodding half-court sets.

How we got here is a fascinating confluence of planning and serendipity, innovation and imitation. The influencers were from a large and diverse cast of characters that included NBA mandarins who wanted to reform the game and coaching iconoclasts who wanted to upend it; athletic freaks such as Nash and Stoudemire who wanted to make best use of their skills; and analytics mavens who saw a market inefficiency that could be exploited with one thing:

Speed.

'The game was bordering on truly ugly'

In early 2001, Suns owner Jerry Colangelo approached then-commissioner David Stern at a meeting in New York with what he felt were urgent concerns for the league. The average score of an NBA game had dropped precipitously to its lowest point since 1955 (the 1998-99 lockout-shortened season excluded). The league was shooting 44.3 percent from the field, the lowest mark since 1969 (again, save 1998-99).

"The game was getting very physical and bordering on truly ugly at times because of the amount of contact and banging," Dallas Mavericks coach Rick Carlisle says. "There was a need for change."

Traditionally, proposed rule changes to the game were the province of the NBA's competition committee, which would initiate a cumbersome process that included the board of governors as well as input from NBA coaches and front-office executives. But Colangelo, a former chair of the competition committee, felt the NBA game had become so repellent and unwatchable that some ad hoc adjudication was in order. Colangelo enumerated some of his ideas for Stern, at which point the commissioner empowered him to appoint a committee and go to work.

"The game was struggling," says Colangelo. "There was a lot of isolation basketball, and there was a lot of standing around. We had defensive guidelines that no one truly understood. It was a mess. Handchecking was a big issue, and there were muggings in the paint."

As recently as 1987-88, 100-possession games had been the NBA norm. But with the exception of a brief blip upward in the early '80s, the pace of play had inexorably been trending slower for decades. Consider that in 1961-62, when Wilt Chamberlain averaged 50.4 points per game and Oscar Robertson a triple-double, the average NBA game featured 107.7 shots per game by each team. By 1997-98, the last season before Michael Jordan's second retirement, that had dropped to 79.7 shots per game -- a 26 percent decline.

Colangelo leaned on one of his mentors, Pete Newell, a legendary coach and basketball luminary. Newell visited Phoenix and Colangelo presented his concerns and general goals the afternoon prior to a Suns game, and the conversation continued at the arena and over a glass of wine following the game. The next morning, Newell delivered a six-page outline on the various concepts and ideas laid out over the course of the previous day.

Soon after, in the early spring, Colangelo's committee, which included heavy hitters such as Jerry West, Wayne Embry, Jack Ramsay and Rod Thorn, in addition to a handful of active coaches and general managers, convened at The Phoenician resort in Scottsdale, Arizona.

The committee plowed through the proposals, which included requiring teams to bring the ball over half court in eight seconds rather than 10. (Colangelo had suggested seven seconds.) The NBA's illegal defense rule, which had existed in one form or another to prohibit zone defenses since the league's earliest days, was scrapped. Instead, the committee proposed the defensive three-second rule, preventing defenders from loitering in the paint but allowing them to defend an area rather than an opponent elsewhere on the court.

"When everyone is scoring and having fun out there, it makes the game so much better. You don't mind waking up and going to work." Amar'e Stoudemire

In May, Colangelo's committee presented the proposal to a group of coaches at the NBA draft combine in Chicago and met some vocal opposition. A contingent of coaches who thrived under slower, isolation-oriented offenses expressed concerns that they didn't have the shooters to contend with the reforms.

"I told them, 'Then you better find a shooting coach,'" remembers Embry.

Under normal circumstances, the community of coaches would have had ample opportunity to contest or even obstruct reform proposals such as the ones being submitted, but in this instance, the ad hoc committee wasn't consulting as much as it was decreeing changes. The rules would take effect that fall, and those who resisted, Colangelo told the group, would find themselves left behind by a more modern game.

"A lot of the slowing down of the game had been the result of stringent illegal defense rules," says Carlisle, whose first season as a head coach, with the Detroit Pistons, coincided with the reforms. "The [defensive three-seconds rule] was a major step toward the game that we have today. Ball movement and creating offensive scrambles for open shots was becoming more of the norm than posting up a great player, having him back in, drawing a double-team."

In the '90s, the post-up had been a central feature of many NBA offenses. Carlisle noted that one of the enduring images for him of the late '90s, when he was an assistant coach with the Indiana Pacers, was watching Mark Jackson deliberately back down New York Knicks guard Charlie Ward, who would squat in a defensive stance that looked like something out of pro football.

But in the nearly 20 years since, the post-up, be it with a big man on the block or a physical guard such as Jackson, has decreased in value in the present-day NBA game.

"One of the reasons the post-up is terribly ineffective these days is because you can double-team the post before the ball even gets in there," says Warriors coach Steve Kerr. "You can pass guys off. You've seen a million times where, like, we switch, Steph Curry has to slide down to a big guy, Draymond Green comes over from the weak side and pulls Steph, Steph runs to the weak side, and now Draymond's got the post-up guy."

This scheme was effectively illegal prior to opening night in 2001. Today, offenses still want to draw two defenders to the ball so they can pick up a 4-on-3 advantage, but rather than feed a big man such as Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Hakeem Olajuwon or Patrick Ewing, they're utilizing pick-and-roll actions with guards such as Curry, James Harden or Chris Paul. It's a far easier way to leverage defenses in 2018, to say nothing of the ability of elite point guards to drain a step-back 3-pointer. Even the best post players of past eras didn't have that at their disposal, nor were there 39 percent 3-point shooters along the perimeter primed for a kickout pass. As post-ups have declined, the game has sped up.

It took several seasons for the full impact of the changes to become evident. Pace ticked upward slightly in 2001-02 and 2002-03 before plummeting again in 2003-04. Only then did the NBA implement the last of the Colangelo committee's proposals, which had the most immediate impact. The league was far more hawkish on handchecking in 2004-05, with a defender allowed only brief contact with a ball handler and no allowance for impeding him.

"It brought back the point guard, who was almost lost," says Colangelo.

In a fortuitous coincidence, the point guard best equipped to take advantage of the new rules had just signed with Colangelo's Suns.

The NBA's fun factory

By Christmas Day, the 2004-05 Suns were 23-3, with two win streaks of at least nine games and only four games with fewer than 100 points scored. Although the majority of players in the rotation didn't have a single set play designed to get them a specific shot at a specific moment, there was a collective feeling on the roster that this was the most joy anyone had ever experienced playing basketball, in no small part because Nash was the best basketball camp counselor in the history of organized play.

"You know you're going to have fun out there on the court," says Stoudemire. "Everyone was getting a chance to score, and as players, we love to score. When everyone is scoring and having fun out there, it makes the game so much better. You don't mind waking up and going to work. You don't mind practicing. You don't mind shootaround because everything is fun."

Although the nucleus was relatively new, friendships were being formed off the court. Team dinners were regularly scheduled, with wine flowing freely. Team meetings were lovefests. While it's impossible to correlate happiness directly to a style of play, one reason organizations have adopted a fast style in recent seasons is the belief that happy players create successful teams.

"That's why it really fries my ass when people out there -- and even players in the league -- said, 'I don't know that Steve Nash should've been MVP.'" Alvin Gentry

It isn't as if playing with pace hasn't always been fun for athletic players. But in an era when players have asserted their power and drive the value of the league, it's vital for teams to offer appealing workplace conditions in order to recruit and retain the best talent. Sometimes those sales pitches include top training facilities with all the bells and whistles, and sometimes it's a system in which players are afforded the freedom to play with speed and instinct and without a harness.

"I think there's many attractive parts of that," says Brett Brown, whose Philadelphia 76ers ranked No. 4 in pace this season. "To go to players and say, 'Come, play for us; we're going to walk it up the court' -- if you're a college coach, you're not getting many players. That's a fact."

With more possessions comes more scoring. And NBA players are rarely happier than when they're putting up numbers.

"It's an easy sell," says Gentry, whose New Orleans Pelicans led the NBA in pace in 2017-18. "It's pretty easy [for a player] to go from 18 points per game to 21 in this system. And 21 is so much different than 18 in this league."

A player averaging 18 PPG for the league's slowest team in 2003-04, the Portland Trail Blazers, would have jumped to 19.5 per night for the 2004-05 Suns, given the same role and efficiency as a scorer. Add Nash's distribution, and bigger leaps were possible. Stoudemire went from scoring 20.6 PPG in 2003-04, his second NBA season, to 26.0 while playing fewer minutes after Nash's arrival.

"That's why it really fries my ass when people out there -- and even players in the league -- said, 'I don't know that Steve Nash should've been MVP,'" says Gentry, who was a Suns assistant coach when Nash signed with Phoenix. "He joined a team that was pretty much exactly the same. We added him and Quentin Richardson. We went from 29 wins to 62 wins."

Through much of the '90s, a basketball possession was commandeered by a coach on the sideline who shouted the set to the point guard, who transmitted that play call to the other four players on the floor. But today's fast-paced NBA teams have tossed away most of the playbook in favor of a series of basic principles and patterns that empower the guys on the floor to make decisions based on feel. Gentry, whose teams were ranked in the bottom half of the league in pace five times in his six seasons as a head coach before his arrival in Phoenix to join D'Antoni's staff, is himself a convert.

"When I first was his assistant, I said, 'He's crazy. You can't play this way in the NBA,'" says Gentry. "I came from an era where you threw it into Patrick Ewing, threw it into Rik Smits and just played around them."

Gentry now runs scrimmages at his practices in New Orleans in which his players have only six seconds to bring the ball across the half-court line and 18 seconds to get off a shot attempt. The imperative to the Pelicans couldn't be clearer: Get into your stuff more quickly and take the first quality shot available. These were principles D'Antoni decreed as sacrosanct in a league in which a set defense in the half court is the greatest impediment to finding good looks.

"It was a relentless willingness to run when it was there, and if not, don't walk the ball up the court," says Nash. "Push, push it, throw it ahead, get the defense on their heels, run into dribble drags, drags, dribble handoff, whatever it may be. But get the defense moving and make plays when they're not completely set."

The "drag" Nash speaks of is the quintessential Suns action of that era and an apt illustration of how a fast-paced team can create structure on the floor without cramping its style. As Nash raced down the floor with the ball -- with Stoudemire trailing at full speed -- Stoudemire would brush Nash's defender, thereby creating utter confusion for a backpedaling defense.

"By the time they react, I'm hanging on the rim," says Stoudemire.

The action was never "called" for Nash or Stoudemire from the sideline or even by Nash in the moment. This was their own freelance operation, guided by their mutual instinct. It's a freedom that's enabling for high-level players. In being given control of the offense, they gain certain ownership over the enterprise. Although there will always be certain individuals who prefer to color by numbers, NBA players are like most creative professionals: They'd rather be left to their own devices than be told what to do.

Mike D'Antoni says it would have been rash of him to change anything after the loss in Game 1 because the Rockets are comfortable with their style of play.

"In a fast system, your shot is predicated by how the defense is playing or how aggressive you are, not on a set play," says Channing Frye, who played on Gentry's Phoenix teams. "Steve [Nash] would know within the first five minutes, 'OK, that's a show. So that's an automatic roll. Now we'll put this shooter right here.' Whenever there's a trigger, Steve or whoever it is will make the right play. The ball will find energy. That was a big D'Antoni thing and became a big Alvin thing. And it's definitely a big player thing. Players want to be rewarded for bringing energy."

D'Antoni's Suns also popularized a trend that would delight players as much as anything since the advent of the NBA charter flight: the 3-pointer in transition. Historically, a team on the break was looking for its best opportunity for a shot attempt at the rim. In Phoenix, players were not only permitted to hoist the ball from behind the arc in transition but also actively encouraged to do so. After all, the payout on such a successful attempt is 150 percent of a successful layup, and shooters such as Nash, Raja Bell, James Jones, Leandro Barbosa and Tim Thomas could drill wide-open 3s with impressive accuracy.

"Catch-and-shoots were part of the game, and the break was a big part of the game," says Pat Riley, who coached the Showtime-era Lakers to four championships. "But we never ran guys to the corner and never ran guys to spots to shoot 3s."

During the 2017-18 regular season, the Warriors attempted 654 3-pointers in the first seven seconds after a change of possession, according to Second Spectrum tracking -- more 3s than any of Riley's Lakers championship teams attempted total. The Warriors made 43 percent of those attempts, equivalent to hitting almost 65 percent of 2-pointers.

Curry has repeatedly said that playing with joy is a core principle for the fast-paced Warriors, and in the ring of joy in Oakland there are few acts more joyful than Curry pulling up on the break for a 3-pointer. His teammate Klay Thompson led the league in 3s in the first seven seconds after change of possession (per Second Spectrum, he converted 90 of 187 attempts for an effective field goal percentage of 72.2 percent).

"They take wide-open 3s because they have the best shooters in the league, maybe in the history of the league in Klay and Steph and Kevin [Durant]," Riley says. "On any break, it's OK to take any 3 that they want to take, shots that in the old days would be considered, 'Get your ass out of the game for taking that kind of a shot.' I don't care who you were."

In two decades' time, a shot that was once regarded as the ultimate act of selfishness has become the octane that fuels the offenses that glide into late spring. Following the Warriors' lead, the league as a whole is pulling the trigger on 3s more quickly. This season, nearly a quarter of all 3s were taken in the first seven seconds of the shot clock after a change of possession, easily the highest rate in the five seasons tracked by Second Spectrum.

Flying on the wings of analytics

"You actually are a product of your experiences," D'Antoni says when asked why he gravitated to a coaching philosophy that valued speed over sets. "When I was a player, I remember toward the end of my career in Europe, we went with two traditional bigs, and sometimes even the third guy was even kind of big. And I just didn't like it. It didn't feel good. And I kept [saying], 'Wouldn't it be better if we just went with one big, and four guys run up and down?'"

A few years later, D'Antoni was coaching the same Olimpia Milano team. He recalls the 1992-93 season, when the team was struggling despite having a talented point guard, Sasha Djordjevic. The offense was gummy and inefficient, devoid of any kind of tempo, and D'Antoni was searching for answers. Comfortable that he had sufficient job security to try something radical, D'Antoni looked to former UTEP standout Antonio Davis, who was nominally a power forward but was languishing on the bench.

"I take my traditional, back-to-the-basket 4 out of the lineup, then put the 3 at the 4 and put another shooter in the lineup," D'Antoni says. "I say, 'Antonio, you're the single big. We'll pick and roll, and I'm spreading the floor, and we're running, and we're going crazy.' We win the next 22 out of 23 games or something. We go from eighth place to third place. And that's it, I'm done."

D'Antoni, and before him, Doug Moe, Don Nelson and Paul Westhead -- not a mathematician among them. No advanced degrees, no pre-existing affinity for numbers and no specific curiosity for the wonders of probabilities. But like baseball's Earl Weaver -- the fiery manager of the Baltimore Orioles who, long before sabermetrics was a prominent school of thought, intuitively knew that getting runners on base was vital while sacrifice bunts were wasteful -- pro basketball's early pioneers of pace had a sense that playing fast might be the best way to play smart.

"We didn't have numbers back then," D'Antoni says. "We didn't have the analytic people. We didn't have anything. So you just kind of went, 'Everybody does it this way. So I'm doing it this way,' and try to coach the best you can, and I always believed in up-tempo."

To the extent that other teams were beginning to invest in analytics, their analysis wasn't pushing them in the direction of playing faster. While prominent statistical analysts such as ESPN's John Hollinger defended the Suns' defense, which allowed a league-high 103.3 points per game in 2004-05 but ranked in the middle of the pack (16th) when evaluated on a per-possession basis, the consensus at the time was that it was difficult if not impossible to play elite defense at a fast pace. As a result, the organizations that invested earliest in analytics -- notably the Mavericks and San Antonio Spurs -- tended to play at a slow pace.

No team took statistical analysis further than the Rockets, who hired then-unknown Boston Celtics executive Daryl Morey with an eye toward replicating the Oakland A's success chronicled in the book "Moneyball." Morey inherited slow-paced coach Jeff Van Gundy, but after replacing Van Gundy with Rick Adelman in 2007 and eventually losing center Yao Ming to career-ending injuries, the Rockets hit the gas. In 2009-10, the first year without Yao, Houston jumped from 19th in possessions per 48 minutes to sixth.

"The game's better, it's more exciting, it's faster, it's more skill and athleticism." Steve Nash

Meanwhile, a more extreme experiment was happening in the G League. The Rockets' affiliate, the Rio Grande Valley Vipers, became a laboratory of sorts for Morey's front office. Starting in 2010-11, the Vipers played at the fastest pace in the G League for four straight seasons while attempting 3-pointers at a historic rate. The big club soon followed suit, playing at the league's fastest pace in 2012-13. When Sam Hinkie left his role as Morey's right-hand man to rebuild the 76ers, Philadelphia replaced Houston as the NBA's fastest team the following season.

Suddenly, a slow pace became evidence that a team was out of touch with the "smart" way to play. Pace has increased in nine of the past 14 seasons, and the rate of change has been, well, fastest over the past six. In that span, pace has jumped 9.6 percent, putting the league in territory not seen since the early 1990s. Suddenly, it's the slow-paced teams that are considered dinosaurs. Pace and space, with the latter referring to the room opened by additional 3-point shooters, are the order of the day. D'Antoni was feted as a visionary when Morey invited him to serve as a featured speaker at the 2015 MIT Sloan Sports Analytics Conference.

"Over time, analytics became more prevalent," Carlisle says. "The potency of the 3-point shot became not only something that was a trend but a reality and a necessity. If you want to get a lot of quality looks at 3s, the answer is to play fast."

A deeper dive, however, doesn't necessarily support the notion that faster is better analytically. It's undoubtedly true on offense, where camera-tracking data has reinforced the value of getting into sets quickly. The sooner a team gets the ball across half court, the more points the team averages on that play, according to Second Spectrum tracking.

Play-by-play data also allows Inpredictable.com to split offensive and defensive pace, which is revealing. While faster offenses again score more efficiently, the reverse is true on defense. That makes sense, given that better defenses will likely force opponents deeper into the shot clock, slowing their pace. As slow-paced contrarians such as Utah Jazz head coach Quin Snyder (whose team was last in pace for three consecutive seasons before speeding up to 25th this season) delight in pointing out, there's almost no relationship whatsoever between how fast teams play and their success over the past five seasons.

Nonetheless, the Rockets continue to play fast under Morey. In 2016, when Houston's coaching job opened up, Morey reconnected with D'Antoni. As the Rockets' head coach, D'Antoni has married his instinctual philosophy with the statistical analysis that supports it. Now his opponent in the Western Conference finals and greatest hurdle to an NBA Finals appearance is the team that cracked the code of wedding a lightning-fast offense with a top-flight defense: the Golden State Warriors.

It's a copycat league

The Suns might have branded fast-paced NBA basketball for the digital era, but Riley vividly remembers facing off against Moe's Denver Nuggets teams of the 1980s. Moe was the NBA's mad scientist, a coach who believed that no player should hold the ball longer than two seconds and that playcalling was the scourge of basketball. He once described his offense as "doing whatever the hell you want." Moe's Nuggets teams led the league in pace in nine consecutive seasons before finishing second during his final campaign in Denver.

"It'd be 127-120, but at the end of the day, in the last three minutes, it didn't make any difference what happened the first 45," Riley says of facing off against Moe's Nuggets. "In the last three minutes, we had Kareem, and that's where it went."

Indeed, despite the "Showtime" moniker and the elegance of the break orchestrated by Magic Johnson, the Lakers never finished higher than sixth in pace in any season coached entirely by Riley. There was certainly a place in the NBA for Moe's Nuggets teams, which advanced to the playoffs each of the nine full seasons he was at the helm, though they reached the conference finals only once (and promptly lost to the Lakers 4-1). Yet aspiring to play at high speed usually consigned a team to novelty status, a throwback to the spectacle of the ABA, not a serious contender for titles in the NBA. Everyone wanted to watch the Nuggets -- but nobody wanted to be them.

"Success begets success," Riley says. "And teams have always tried to mirror the teams that win championships."

"Golden State put things over the top. Once someone actually won a championship playing fast and playing small, that became a game-changer." Rick Carlisle

In the years that followed the dominance of the Lakers and Celtics of the 1980s, the Pistons -- led by Isiah Thomas, Joe Dumars, Bill Laimbeer and Dennis Rodman and coached by Chuck Daly -- were handsy and brutish. Their two title-winning teams during that era finished 25th of 25 and 26th of 27, respectively, in possessions per game.

"When the Pistons had their success, that led to more teams trying to control the game defensively and play with physicality and do it in a different way than the Lakers were doing it," Miami Heat coach Erik Spoelstra says.

With the Pistons leading the way, the pace of the NBA game slowed dramatically after finding a pleasant stasis for much of the 1980s. Between 1988-89, Detroit's first championship, and 1996-97, the league's average pace declined more than 11 possessions per 48 minutes.

The Suns teams of the 2000s enjoyed more success than Moe's teams in Denver and Nelson's brisk Warriors teams, but in the highest ranks of the NBA's brain trust, this brand of basketball was still dismissed as gimmickry. A theory had to succeed in practice, at which point it would be not only accepted but also imitated widely.

"What impacts the change and emulation most is whoever wins the championship. You just see it immediately," Spoelstra says. "We saw it after San Antonio, for example, beat us in the Finals [in 2014]. The next year, it seemed like more than three-quarter of the teams were trying to run the Spurs' offense, their after-makes early offense, and everyone was talking about quote-unquote 'beating teams with the pass' and 'how many passes can you get in a possession.'"

There's statistical backing for Spoelstra's observation. Since the ABA-NBA merger, when the champion has played faster than league average, NBA pace has increased the following season 56 percent of the time. When the team that wins the title plays slower than average, that flips and pace declines 60 percent of the time.

When Kerr arrived in Oakland in 2014, he brought with him a hybrid of offensive sensibilities -- the Spurs' pass-happy offense cited by Spoelstra but also D'Antoni's system (including hiring Gentry as his lead assistant) -- and unified them into a coherent structure with like-sized, versatile players. The Warriors trounced the NBA en route to their first of two championships in 2015, topping the league in possessions per game by such a wide margin that there was as much distance between the Warriors and No. 2 Houston as there was between Houston and No. 8 Sacramento.

"Golden State put things over the top," Carlisle says. "Once that happened, once someone actually won a championship playing fast and playing small, that became a game-changer."

Pace was already trending upward by the time the Warriors won the title, but the increase of 1.8 possessions per 48 minutes the following season was the fourth-largest single-season jump since the merger. It has increased again each of the past two years, making NBA games as fast as they've been in a quarter-century. In fact, other teams have passed Golden State. Despite playing faster than they did in 2014-15, the Warriors ranked just fifth in pace this season.

A league the Warriors were running away from just a few short years ago has refashioned itself and copied the avant-garde.

The revolution is being televised

As prisoners of the present, we're inclined to forget that trends are often impermanent, momentarily outliers in cycles that swing from end to end. Who in 1989 would've guessed the speed of play would've dropped 10 possessions per game in less than a decade's time? Yet not every development is a blip. Some are stages of evolution, part of a march toward a more advanced being or, in this case, a more progressive game.

Is the 100-possession game now an intrinsic feature in the NBA, or will a mighty team in the future challenge what we came to believe was a norm? It's difficult to imagine today's game in which speed and athleticism are rewarded to such an extreme degree deliberately returning to an age when wrestling for position in the post was the most common objective in a basketball possession -- even if that action results in a kickout to an open 3-point shooter.

"The best way to beat Golden State is probably not to out-Golden State them." Erik Spoelstra

"I think things are cyclical, but it is hard to envision because the game's better, it's more exciting, it's faster, it's more skill and athleticism," says Nash. "The game is aesthetically great, financially great, and the rules aren't going change because of those by-products. So where are we going to develop one-on-one low post players? So we'll see fewer and fewer kids with the skills to play in the post, which is only going to further deepen the need to play the way the game's played now."

Yet it was also difficult to imagine anyone developing a defense that could contend with a physical specimen like Shaquille O'Neal controlling the game down on the block, helpless defenders hanging onto his limbs for dear life. This is a challenging thought exercise for ambitious NBA coaches, who are ever on the lookout for an innovation that give their team an advantage. No scheme is infallible, and no team -- particularly in a league with a salary cap -- is immune to the vagaries of a game that has always been fickle.

"What if that's the only way we could beat a team like Golden State or Houston?" asks Spoelstra. "What if there was a team with great size but that size also had the agility and versatility to defend small? If you could absolutely punish a small speed team then it could change the paradigm again. There's nothing absolute when you're talking about competition. It will always evolve. Things will go back and forth. The best way to beat Golden State is probably not to out-Golden State them."

This might explain how the Mike-D'Antoni-coached Rockets, who ranked 23rd in pace this season after New Year's Day, and the get-and-go Warriors are averaging a modest 97 possessions per game in the first four games of this series. In many respects, Harden vs. The Warriors in this series speaks to a major confluence occurring in today's NBA: More versatile Warriors-y rosters -- the Rockets included -- are moving to switch-heavy defensive schemes. At the same time, ball-handling guards who excel in isolation and attack defenses are all the rage.

Add it altogether, and you get Harden isolating 83 times in four games during this series, time and again deliberately working to draw his preferred defender -- perhaps Curry or big man Kevon Looney -- against the switch. He'll proceed to pound the ball into the floor as the shot clock winds down inside of five seconds, only then making his move: A step-back 3, or a patented stutter-step drive. This brand of basketball might offend some aesthetic sensibilities, but it's brutally efficient: 1.32 points per chance in this series, according to Second Spectrum. Just as teams copy the blueprint of champions, might players look to an MVP and a team that won 65 games this season and replicate their style?

As has often been the case throughout history, revolutionaries who successfully storm the gates eventually become the establishment.