Editor's note: This story originally ran on June 3, 2015.

LeBron James is one of the greatest athletes the world has ever seen.

The body of an NFL linebacker. The speed of a track star. The vision and precision of a marksman. The basketball mind of a computer. All rolled into one package barreling right at you on his way to the rim.

How do you defeat such a modern-day Goliath?

With a slingshot, of course.

In the NBA, they call it a 3-pointer.

In dismantling the two-time champion Miami Heat in last year's NBA Finals, the San Antonio Spurs fired up more 3-pointers (23.6 per game) than any championship team in league history and averaged more 3s than even the most 3-happy Phoenix Suns squad in the "Seven Seconds Or Less" era.

But Spurs coach Gregg Popovich is hardly proud of it.

"I can't be stubborn," he explains, "just because I personally don't like it and think it mucks up the game."

He's not alone.

Pat Riley, the dominant coach of the 3-pointer's first decade in the league, called it a "gimmick." Larry Bird, one of that era's most dominant shooters, says, "I really don't like it."

But it's impossible to deny the impact of the shot on today's NBA.

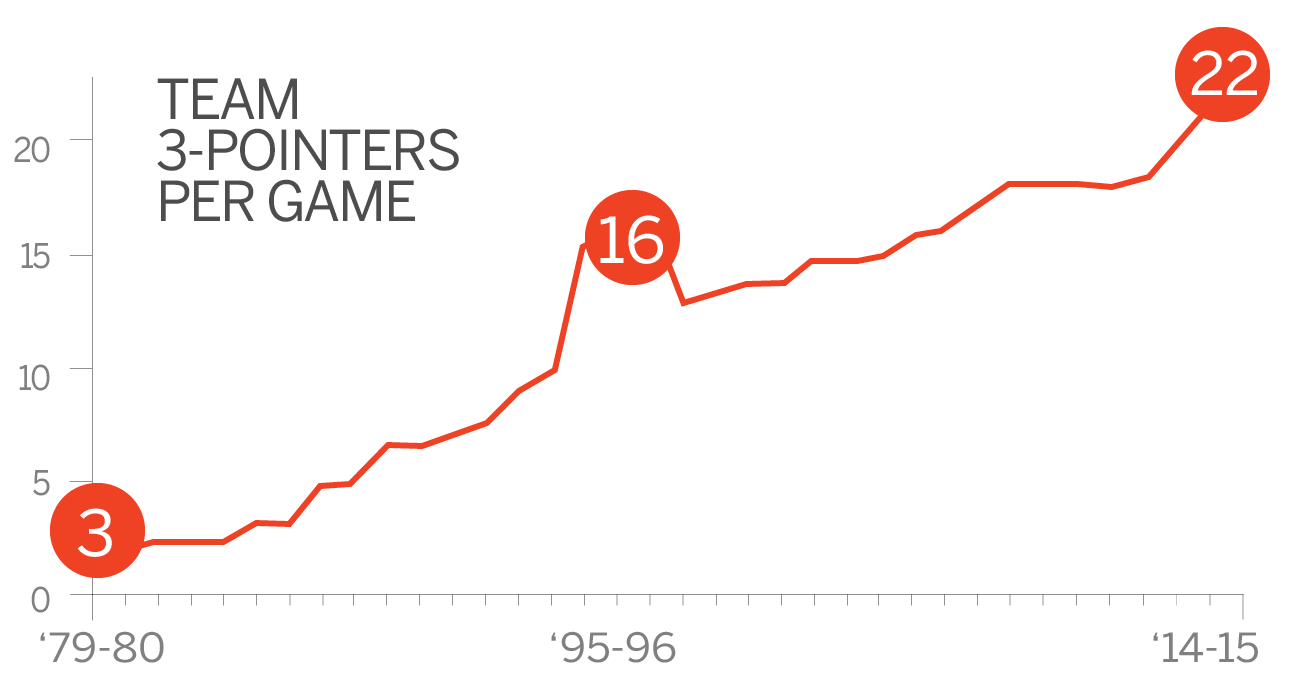

This season, the league shot over 55,000 3-pointers. The average team today shoots 22.5 3-pointers a game, a rate that would have led the league in 2000-01. Stephen Curry won MVP while breaking the 3-point record. Take a look at the 10 most frequent 3-point shooting teams in NBA history and you'll see five that also made this year's playoffs.

This year's NBA Finals might as well be a celebration of the 3. The only teams in NBA history that have averaged more 3s per game in the playoffs than this year's Cleveland Cavaliers (30.3 3-point attempts per game) and Golden State Warriors (29.1 3-point attempts per game) were the 2007 Warriors, who upset the No. 1-seeded Dallas Mavericks in the first round, and the 2013-14 Atlanta Hawks, who nearly did the same against the top-seeded Indiana Pacers.

Now the long shots and the juggernauts are utilizing the long ball to great success.

As John Hollinger wrote in 2009, there's a new motto in today's NBA: Live by the 3 or die. "Few stats correlate better with winning than 3-point attempts," he wrote.

"We all know if you don't shoot the 3, you're probably not going to win," says Popovich, whose Spurs set an NBA Finals record for 3s last year. "Everybody in the league shoots the 3-point shot well and knows the importance.

"I still hate it."

This is the story of how traditionalist coaches and players managed to keep the 3-pointer at the fringes of the NBA game ... until now.

Rise of the 3-pointer

Bombs away! The NBA has seen a steady rise in 3-point attempts since its introduction in the 1979-80 season.

The gimmick

By 1967, former NBA great George Mikan had become the commissioner of the NBA's upstart rival, the American Basketball Association. Desperate for fans, the ABA implemented the 3-point shot for the 1967-68 season to juice up the action, adopting it from the defunct American Basketball League, where it originated.

"We called it the home run, because the 3-pointer was exactly that," Mikan said in "Loose Balls," Terry Pluto's definitive history of the ABA. "It brought the fans out of their seats."

Kentucky Colonel guard Louie Dampier was immediately smitten. The 6-foot guard made 794 3-pointers in his nine seasons in the ABA, nearly 300 more than any other player.

"Louie's the one that did that before anybody," says ESPN analyst Hubie Brown, who coached Dampier for two seasons. "One of the best ever."

Once in practice, Dampier led a 2-on-1 fast break. But instead of attacking the basket, he dribbled right up to the 3-point line and launched a jumper from 25 feet away. Today, we wouldn't bat an eye. But then?

"I stopped practice," Brown says.

But the shot added enough excitement to the game that the NBA eventually brought it along, instituting it in the 1979-80 season, three years after the ABA merger.

George Karl, a veteran player and coach of both leagues, says the shot's coming from the ABA is precisely what doomed it in the eyes of NBA traditionalists. "The NBA was rebellious against the 3-pointer at first because it was born out of the ABA," Karl said. "For years, the NBA guys kind of said, 'That's not a good shot! That's playground basketball!'"

Pat Riley's Los Angeles Lakers were the dominant team of the shot's first decade. In 1981-82, Riley's first season as head coach, the Lakers made a total of 13 3s. All season. And still won the championship.

"It just wasn't something that we used back then," Riley says. "I think it was seen as more of a gimmick in the beginning."

"There was a philosophy throughout the league about how to play. There wasn't an emphasis on the 3-point shot even though it was there. It's almost as though anytime you wanted to take a 3-pointer, it's because you were down two and you could win the game. Or you were down three and it could get you back. And you started to sling 'em."

The team eventually gained some regard for the shot and used it to create space for post players. By the 1986-87 championship season, Riley's Lakers ranked sixth in the NBA in 3-point frequency.

"Still, the 3-point shot was not something that we lived or died with," Riley says. "We rammed the ball down their throats."

Guard Byron Scott was one of the team's best gunners, attempting more than 2,000 3-pointers in his NBA career. As head coach of the Lakers, Scott still sounds like Riley. "We always said, 'You live by the sword, die by the sword,'" Scott said, whose Lakers ranked 26th in 3-point frequency this past season. "We played off the post. We didn't necessarily use it as a weapon."

3-point shootout: Steph Curry vs. Larry Bird

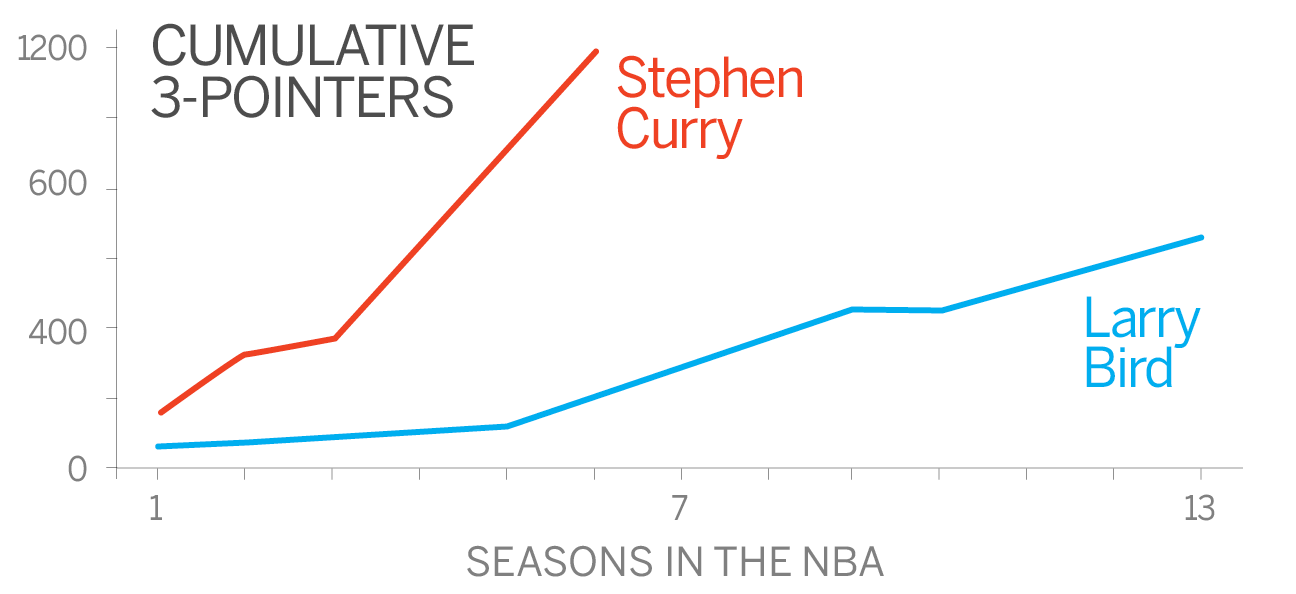

Bird may be remembered as one of the best long-range shooters, but his 3-point production's got nothing on Curry, who continues to smash records.

Not for the Birds

Larry Bird's shooting is the stuff of legends.

"Larry was an amazing shooter," says Danny Ainge, Bird's Boston Celtics teammate for 7½ seasons. "The amazing thing about Larry was how many contested shots Larry could make. He was like Dirk Nowitzki today. Guys were all over him."

But while Bird's 3-point skills are well-known, the shot is not something he practiced, thought about, liked or even did very often. Bird never averaged more than three 3-point attempts a game until he turned 30.

"I can remember if a guy was out at the 3-point line, you wouldn't even go out there and challenge him," Bird says. "Shoot, we didn't guard anybody out there. We dared them to shoot that shot."

In the second season with the 3-pointer, the 1981 championship Celtics team shot 241 3-pointers as a team, the second-highest frequency in the NBA. (For reference, Stephen Curry shot 242 3-pointers this season ... after the All-Star break.) But K.C. Jones, who took over as coach in 1983-84, didn't initially see it as a weapon.

"The only time I remember anyone saying anything about 3-point shots, K.C. Jones told us one time that we took too many 3-pointers before a game," Bird says. "We were playing New York. We got out, Robert Parish tips it to Danny Ainge, who takes two dribbles and shoots a 3-pointer. And that was the end of that."

M.L. Carr, a teammate of Bird's who also played in the ABA, had a saying: "Hey, they didn't put that line on the court for decoration," Ainge remembers. "It's meant to be used."

With Carr's advice, the Celtics ranked in the top 10 in 3s attempted in each of the five seasons of Jones' run as head coach, during which Boston went to four straight NBA Finals. Bird led the league in 3-pointers in 1986-87 with 90. The next season, Ainge eclipsed that total by the All-Star break and finished with 148.

"People weren't leaving Larry Bird open like they were leaving Danny Ainge open," Ainge says. "He didn't grow up playing it, and as a primary scorer, it was more difficult to do.

Like Riley, Bird saw the shot as crucial only in special situations.

"If we were up one or tied or maybe down one, we tried to hit a 3-pointer," Bird says. "It does take something out of the other team. That's the way I like to use it. It's a killer shot. Just watch the opposing team. Just watch 'em. Their heads go down. There's usually a quick timeout and the coach looks like he's mad. Now, you feel like it's a desperate situation. I always called it icing the game. It's very deflating.

"It's really funny," Bird says, "I never even practiced 3-pointers. We might have thrown up only a couple of them. The only time I practiced them was right before the 3-point contest in 1988. Danny [Ainge] would get the rack out and we'd rebound and throw the ball back out and shoot some 3s. But we didn't fire up 100 3s after every practice."

Despite winning the first three 3-point contests ever, the shot never grew on Bird.

"I don't know why I never liked it," Bird says, "But I liked it only in certain situations."

So what changed? Who started the 3-point evolution?

"God, you know, I can't remember who the coaches were that used it to their advantage ..."

Bird trails off and pauses to think.

"Oh," Bird suddenly blurts out. "It was Rick Pitino."

Pitino's Bombinos

Before the national championship at the University of Kentucky, before taking the New York Knicks to the playoffs, before the not-so-successful stint with the Celtics, before he led the Louisville Cardinals to Finals Fours, Pitino was presented with a task: Resurrect the Providence Friars.

The men's basketball program was on life support, finishing tied for last in the Big East in 1984-85, the season before Pitino arrived.

"I came in, obviously, without hope or talent," Pitino says, "I needed an offensive gimmick to turn this thing around."

First, he used a maniacal full-court pressure to create havoc. That worked. Led by junior point guard Billy Donovan, the Friars went 17-14 in his first season and made the NIT.

Another edge would fall into his lap the following season.

"When the 3-point shot came in, I decide that I was going to tell my team we were going to lead the nation in 3-point shooting," Pitino says. "We were going to take 15 3-pointers a game, and we were going to lead the nation."

The Friars faced a Soviet Union national team featuring stars such as Arvydas Sabonis and Sarunas Marciulionis in a preseason exhibition ahead of the 1986-87 season. The Soviets, veterans of the international game's 3-point line, took 27 3-pointers and crushed the Friars.

Turned out, 15 wasn't going to cut it.

"I realized my number was too small," Pitino says.

So he raised the bar.

"Twenty-five 3-pointers a game," Pitino recalls.

Donovan remembers it differently.

"I think he actually told us to shoot 35 a game," says Donovan, now the head coach of the Oklahoma City Thunder. "That was totally against conventional wisdom. Coaches were really opposed to the rule and opposed to adjusting their offense to the 3-point line. You had guys who were coaching 25 and 30 years who were used to a certain way, and they had to reevaluate things philosophically."

"In the beginning, everybody thought I was a mad scientist. In the end, everybody realized how potent a weapon it was." Rick Pitino

Pitino took special pride in the uniqueness of his team's approach, noting that a who's who of opposing teams -- Rollie Massimino's Villanova, John Thompson's Georgetown, Lou Carnesecca's St. John's -- failed to hit a single 3 against Providence during Big East play.

The Friars went 25-9 that season and reached the Final Four as a No. 6 seed, upsetting No. 2 Alabama and top-seeded Georgetown in the process. They led the nation in made 3-pointers (280) and shot 19.6 3-pointers per game.

Days after reaching the Final Four, Pitino was hired as head coach of the New York Knicks, who had finished the 1986-87 season tied for second-to-last in the NBA.

Pitino was gifted Thompson's Georgetown protégé, Patrick Ewing, but that wasn't enough. Pitino wanted to shoot 3s to space the floor around Ewing. In his first season, the Knicks rose all the way to the playoffs, shooting the third-most 3-pointers in the league despite the absence of an array of sharpshooters.

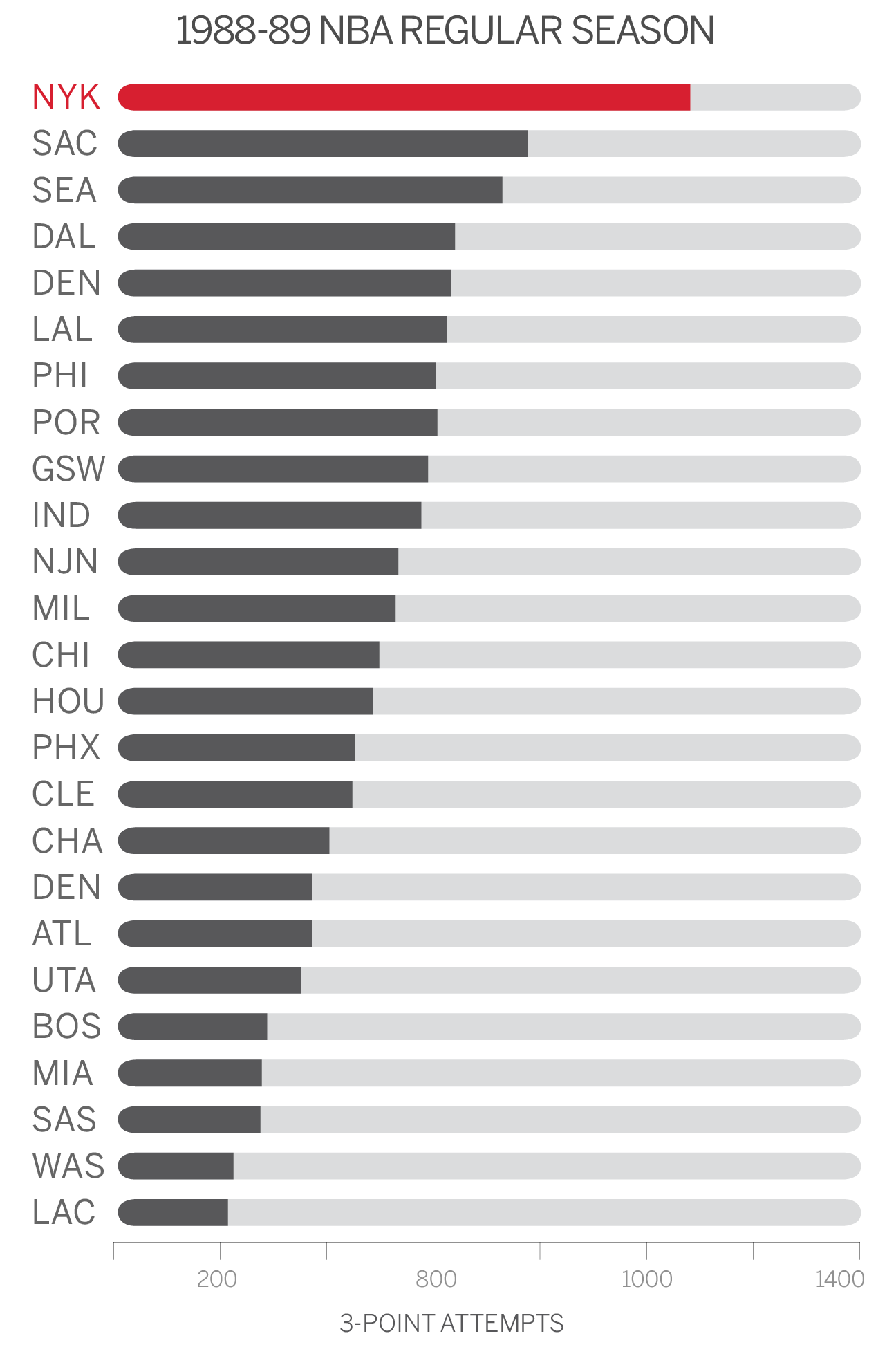

In Pitino's second season, the Knicks went 52-30 and led the NBA in 3-pointers made and attempted, thanks to Johnny Newman, Trent Tucker, Gerald Wilkins and Mark Jackson. They took an NBA-record 1,147 3-pointers, more than double the league average. The previous record was 705.

"We had it rolling in the Garden," Pitino says. "It was at 60 percent capacity before I got there, and then suddenly it was full. I remember we made every bonus clause based on attendance and wins."

New York newspapers put "Pitino's Bombinos" all over their pages in honor of the coach's radical strategy.

But there was a method to his madness. One of four conditions had to be met for Pitino's players to have the green light on 3s: on offensive rebounds, on dribble penetration, inside-out plays and on the break after ball reversal. In any of those situations, it was bombs away.

The Knicks swept Charles Barkley and the Philadelphia 76ers in the first round that year. But in the Eastern Conference semifinals, they ran into arguably the greatest force in basketball history: Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls.

Jordan had a superhuman series, averaging 35.7 points, 9.5 rebounds and 8.3 assists, including two free throws to clinch it in Game 6 that Pitino says he will never forget.

"I always say this ... if we would have had the seventh game coming back home, I really believe we would have won a championship," Pitino says. "Because we had the Pistons. The Bad Boys could not handle us." The Knicks indeed beat the Pistons in all four regular-season matchups. but Jordan defused the Bombinos' run.

That summer, Pitino took the head-coaching job at University of Kentucky, where he later won a national championship. His Knicks' 3-point-attempts record would stand untouched until five seasons later, when the Houston Rockets won back-to-back titles in the mid-90s, in part by embracing the shortened 3-point line.

"In the beginning, everybody thought I was a mad scientist," Pitino says of his use of the 3-pointer. "In the end, everybody realized how potent a weapon it was."

The Great Bombinos

Rick Pitino's Knicks let 'em fly in the coach's second season as head coach, which helped turn a struggling franchise into a contender.

The corner store

"I've never been the biggest advocate of the 3-point shot," Larry Brown says with a knowing chuckle.

Brown is among the most influential coaches in the game, but a 3-point fan he is not. His NBA teams ranked in the bottom 10 in 3-point frequency for 21 straight seasons, often dead last. He coached Reggie Miller -- widely known as one of the finest shooters ever -- in Indiana, and yet none of his four Pacers teams ranked better than 23rd in 3-point frequency.

In October, Brown, now the head coach at Southern Methodist University, told reporters he'd like to abolish the 3-point line and instead award three points for layups. He wasn't kidding.

"My biggest concern," Brown says, "is when I go to the playground or I watch kids when I go to a high school game, everyone's jacking up 3-point shots in warm-ups. I don't see our game improve. I don't think the people who invented the game wanted to put more emphasis on outside shooting, but that's my personal opinion."

Gregg Popovich is one of the half-dozen current NBA coaches who hails from the Brown coaching tree -- and was the best man at Brown's wedding. He also shares Brown's displeasure with the long ball.

"I hate it as much as Larry does," Popovich says.

But performance always trumps preference, and Popovich has utilized the 3 to great success. His Spurs squad popularized the corner 3 -- i.e., near the baseline -- which is shorter in distance than standard 3s and trickier to defend. His teams always featured elite 3-point shooters: Steve Kerr, Bruce Bowen, Danny Green, Manu Ginobili, Michael Finley, Brent Barry and Matt Bonner, to name a few. Over the past decade, only six teams have shot more 3s than Pop's.

Still ...

"To me, it's not basketball," says Popovich, "but you got to use it. If you don't use it, you're in big trouble. But you sort of feel like it's cheating.

"People don't cut as much," he adds. "People don't move without the ball as much. We all tend to run the same play to get the open guy. Everybody runs a pick-and-roll, runs a guy down the middle and either you gotta pick him up or not. And you got to decide what you're going to do when the guy pops out for the shot. It's pretty boring, actually."

Under Popovich, the Spurs have taken 1,000 more corner 3s than any other franchise since the NBA began tracking the shot in 1997 (9,282) and they are the only team to convert over 40 percent of them over that time.

Rising of the Suns

Some might say the 3-pointer's rise was inevitable. But don't tell that to Pat Riley.

"The evolution of it wasn't natural," Riley says. "It was man-made. It was thought-out."

The man who made it happen, in Riley's view, is Mike D'Antoni.

From 2004-05 to 2007-08, D'Antoni's "Seven Seconds or Less" Phoenix Suns used speed and 3-point shooting to win over 70 percent of their games.

"We tried to fight stereotypes that you couldn't win that way," D'Antoni says. "We didn't play inside-out. We just played."

The genesis of D'Antoni's coaching philosophy came during his days playing in the ABA, where the 3-pointer reigned. As a coach, he won league championships in Europe with a heavy emphasis on the 3-ball.

"In Europe, it just made sense because the line was a little bit closer," D'Antoni says. "We started shooting a lot of 3s in Europe and we were criticized. But we won a championship, so we weren't criticized too much. It was like, why wouldn't we shoot it?"

In the NBA, D'Antoni still felt the prejudice against the 3-point shot and used it to his advantage.

"When you go back to the history of the 3-point shot, it was tied with an undisciplined type of basketball, so there was a stigma to it," D'Antoni says. "As soon as you launched a 3 that was ill-advised a little bit or you took more than what was the perceived normal, the stigma was that you weren't well-coached."

In truth, his system kept things simple. Spread pick-and-roll. Deploy big men who could shoot.

But unlike Riley and Pitino, D'Antoni wanted to space the floor to unleash his point guard, Steve Nash, rather than his bigs.

"How can you unclog the lane?" D'Antoni says. "If we became dangerous out on the 3-point line, we could really get into the lane and get layups. All I wanted to do was get layups. That's all I was really searching for. And so, you can shoot more 3s, have a stretch 4. Wouldn't it be great if your 5 could shoot 3s also? It goes right on down the line."

When D'Antoni took over, he made the unconventional move to slide Shawn Marion from small forward to power forward and make Amare Stoudemire his starting center. That replaced the lumbering 7-footer Jake Voskuhl with another 3-point shooter, Quentin Richardson, on the wing. Richardson led the league in 3-pointers in 2004-05, D'Antoni's first in Phoenix. Nash won MVP, and won another the following season.

Nash saw his job as simply finding his team the best possible shot. "You're constantly analyzing data," Nash explained in a recent ESPN the Magazine interview. "Every split second there's a new angle, a new possibility." The data often suggested shooting more 3s.

When D'Antoni took over as head coach in Phoenix, the average NBA team shot 14.9 3-pointers per game. By the time he left, the league average was 18.1. The rise of 21 percent, at the time, was the largest four-year increase since the 3-point line was shortened in late 1990s.

But even though D'Antoni's fingertips are all over today's NBA, his Phoenix teams never did win a championship. Pitino had Jordan; D'Antoni had the Spurs, who ended the Suns' playoff run three times in four years.

"I'd like to blame Michael Jordan, too, but we didn't play him," D'Antoni laughs. "We played against the San Antonio Spurs -- the three years that I thought we really had a shot to win it."

Climbing to D'Antoni's 'mountaintop'

You can't out-Shaq Shaq.

That was one of D'Antoni's favorite sayings in his Suns years. And a month before the Miami Heat's 2012 championship parade, it became a rallying cry for Erik Spoelstra when the LeBron James-Dwyane Wade-Chris Bosh experiment looked in doubt.

"You can't out-Hibbert Hibbert," Spoelstra told his staff, past midnight in their upstairs lair at AmericanAirlines Arena. The Eastern Conference finals was tied 1-1, but the Indiana Pacers' imposing front line of David West and 7-foot-2 Roy Hibbert was crushing the Heat, who had lost Bosh to an abdominal strain.

"We couldn't score," Spoelstra says. "We weren't going to win that series without thinking outside the box."

Inspired by Chip Kelly, who emphasized speed over size as the football coach of the Oregon Ducks, Spoelstra had spent the entire season talking about "position-less" basketball. But he didn't turn his words into reality until that night in May.

"Shane Battier was my Shawn Marion," Spoelstra says. "He unlocked everything."

Spoelstra decided that night he would start Battier in Game 3 and use his 3-point attack to open up the paint against the colossal Pacers frontcourt. Battier would have to play as a big man for the first time in his career.

The Heat brass, including Riley, wasn't exactly sold.

"They all told me to sleep on it," Spoelstra says with a laugh. "They thought I was nuts."

In Game 3, the Heat were blown out 94-75. Dexter Pittman, who started at center, was ejected in the first quarter. But Pittman was the decoy. Battier was the key.

"I walked through the tunnel that night after Game 3 knowing that was how we were going to play, regardless of the score," Spoelstra says. "I shut out all the noise. Everyone thought we couldn't win that way, certainly not a title. I didn't care."

Spoelstra didn't budge. With Battier stretching the floor for James and Wade, the Heat blitzed the Pacers in Game 4. And Game 5. And Game 6.

A month later, with Battier and Bosh each slinging 3s in the Finals against the Thunder, the Heat won the championship, their first of two in the Big Three era.

That night, D'Antoni received a text message from Spoelstra.

"This one's for you," it read. "We climbed the mountaintop."

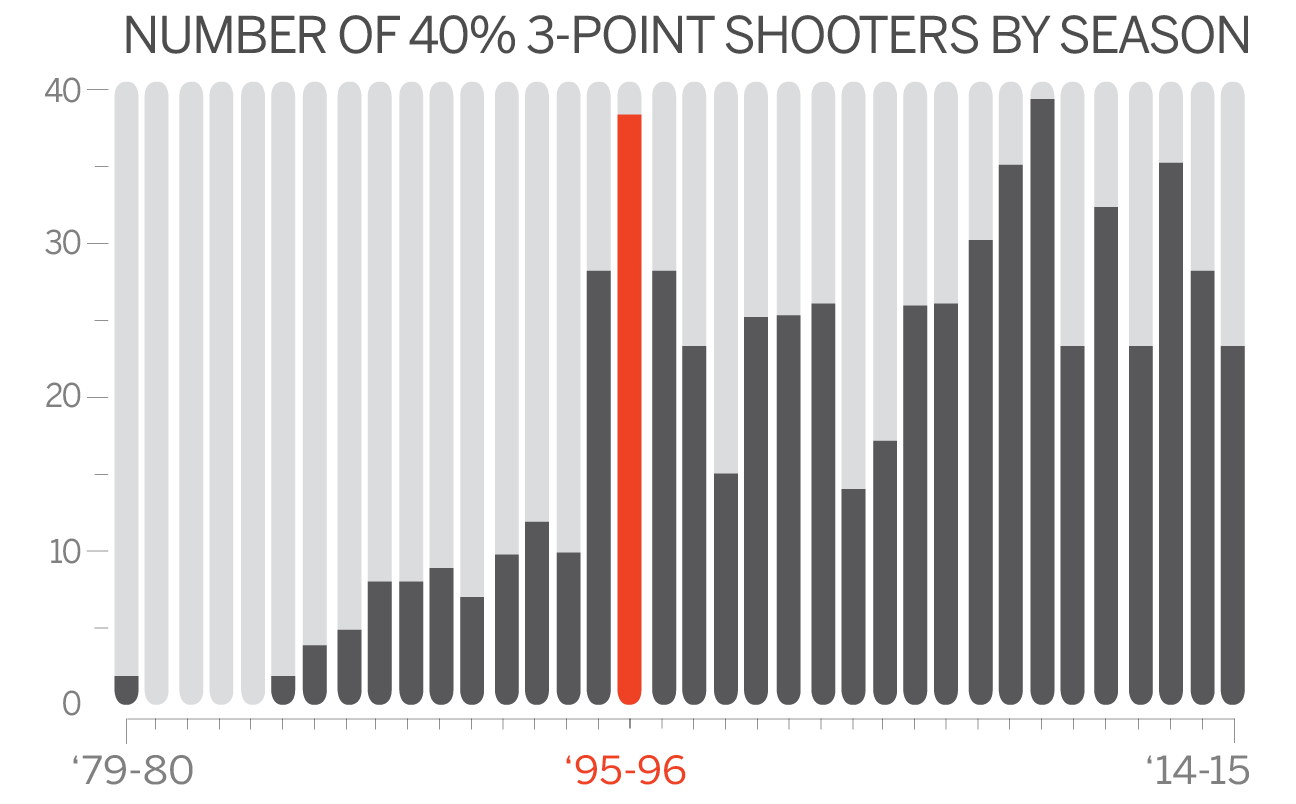

The Heat went all-in on 3-point shooters thereafter, signing Ray Allen in the offseason. With Allen and Battier parked in the corners, the Heat went 66-16 the following season and ranked third in the NBA in 3-pointers made while breaking the NBA record for most corner 3s in a season (309). Five Heat players shot over 40 percent on at least 150 attempts -- the first team in NBA history to ever pull off that feat.

"Until someone broke through and won a title," D'Antoni says, "you just had the old-time players who became talking heads that just never bought in because they didn't play that way, and I can understand why. Until somebody won a championship -- and that somebody was Miami, actually, but then there's the LeBron James factor, and they all say, 'Oh, that's because of LeBron James, not because they played differently.'"

But, in reality, the Heat won because of LeBron James -- and because they played differently.

The 40 percent club

Despite some early reluctance and learning curves, the 3-pointer was embraced in the mid-90s -- and has flourished in today's NBA.

The numbers add up

"The Main Street general store did not have to change until Walmart came into town," says Daryl Morey, the Houston Rockets general manager.

If Walmart is about volume, so are Morey's Rockets, the most 3-point-happy team in NBA history. In 2014-15, Houston fired up a record-breaking 32.7 3-point attempts per game. No team had previously ever averaged more than 30 per game.

It's really no surprise that the team takes such an unconventional approach, given the guy they've chosen to make the decisions.

When the Rockets hired Morey to run basketball operations in May 2007, he was the first of his kind -- a numbers guru without any playing or coaching experience above the high school level.

But Morey saw reams of evidence that 3-pointers were strategically undervalued. And so he built his franchise, from top to bottom, around the long and the short -- 3s and shots at the rim.

The result: The Rockets beat the odds this season and snagged the No. 2 seed in a nasty Western Conference despite losing Chandler Parsons in the offseason and Dwight Howard for half the season to injury.

"As time has changed, minds have changed," Riley says. "The percentages have changed. People have gone to the computer and the other models. Obviously, they think this is what works."

To Hubie Brown, the recent rise of the 3-point shot stems from several different root causes that includes rule changes that let ball-handlers enjoy more breathing room for drive-and-kicks, as well as prevent loading up in the paint. But Brown emphasizes that the mathematics behind the 3-pointer never really caught on at the coaching profession for decades.

"A lot of people will laugh because everyone's accustomed to the 3-point shot now," Brown says. "But we as coaches had to be schooled within the 3-point game and the math behind it. For me, at the time in 1975, it was an adjustment for me to be thinking under pressure in the game going down to the end, 3 versus 2 and 2 versus 3. Today, it's taken for granted that you understand all that."

Math didn't drive D'Antoni's philosophy, but it certainly came in handy against the skeptics.

"Analytics have really helped," D'Antoni says. "They've shown statistically that it works. You were able to counter, 'Well, you're shooting too quick, too many 3s with, 'Yeah, but we're shooting what translates to 60 percent on 2s. It makes no sense to shoot more 2s.'"

Rockets coach Kevin McHale, a paint virtuoso, was groomed in the old-school mold. The average NBA team in 1992-93, McHale's last season in the NBA, took nine 3-pointers per game. But one of Bird and Ainge's former running-mates was sold on the percentages that Morey laid out years ago. The Rockets now regularly shoots nine 3s in a quarter.

"To me, it's pretty simplistic," McHale says. "If you're going to shoot a 20-footer, you might as well shoot a 22-footer and get an extra point. I mean, stand behind the line rather than on the line."

In the inaugural year of the 3-pointer in 1979-80, there were two players who shot 40 percent on at least 100 attempts -- Bird and Chris Ford, both members of the Celtics. Remarkably, the NBA would have to wait until 1984-85 for another qualified 40 percent shooter. When the 3-point line was shortened in 1994-95, we saw 28 such shooters, almost tripling the previous season's number. Today, there are 23.

A game-changer

On a Sunday afternoon in May, Knicks president Phil Jackson couldn't help himself. With several 3-heavy teams trailing 2-1 in their second-round playoff series, Jackson fired off a tweet to his 842,000 followers:

"NBA analysts give me some diagnostics on how 3pt oriented teams are faring this playoffs...seriously, how's it goink [sic]?"

The barb went viral, generating over 2,000 retweets -- most of which came later, once the egg hit Jackson's face.

The comebacks began almost immediately, and the final four left standing in the 2015 playoffs were also among the league's top five teams in 3-point makes in the regular season. (The Clippers, who were one win away from the conference finals, were the other 3-happy team.)

But Jackson, whose Knicks set a franchise record for losses while ranking in the bottom third in 3-point attempts in his first year as team president, isn't alone in his 3-point stance. Even though Spoelstra's spread offense added to his championship-ring collection, Riley still isn't sold on the 3-pointer, either.

"Today, there's too much emphasis on the 3-point shot," says Riley, the Heat president. "Erik [Spoelstra] and I talk about this all the time, because my style of basketball is '3 yards and a cloud of dust.' That's how I was raised. That's how I was coached. I'm not really part of this craziness. Just layups and 3s. The whole midrange is dying. This is all borne out of what people call analytics."

Charles Barkley caused a ruckus on TNT in February by saying "analytics is crap" and that Morey was "one of those idiots." Barkley has often bemoaned the "jump-shooting" Warriors for their lack of toughness inside.

Ainge was teammates with Barkley on the Suns team that went to the NBA Finals in 1993, and he points out that team led the league in 3-point and free throw attempts, two pillars of analytics.

"I think there's a disconnect in the communication of analytics like there has to be some sort of separation," Ainge says. "When I played in Phoenix with Charles, we shot a lot of 3s."

With respect to the 3, Bird leans toward Barkley's side of the spectrum. When Bird, the Pacers' team president, feels Indiana is dying by the 3, Bird offers coach Frank Vogel his two cents.

"Back when I played, we just didn't shoot it that much. Now, hell, if you're not firing up 30 3s, you're not playing basketball." Larry Bird

"He likes them," Bird says. "We have a lot of plays to get the 3-point shot. I have on occasion told him, 'You better quit shooting them 3s.' But it's part of his offense."

"When I go in there now after practice, that's all these guys do -- they shoot 3s," Bird says of the Pacers. "And they always tell me, 'Man you must have shot millions of 'em to get that good.' Well, I didn't shoot any!"

But for all his opposition to the 3-pointer, Bird sees the appeal of Stephen Currys, Klay Thompsons and Kyle Korvers.

"Back when I played, we just didn't shoot it that much," Bird says. "Now, hell, if you're not firing up 30 3s, you're not playing basketball."

As the gatekeeper of the NBA game, league president of basketball operations and former team executive Rod Thorn loves the way the game is tilting.

"Some from my era think there are too many 3-pointers," Thorn says. "But the game has changed, there's no doubt about it. The fans love the game and the way it's being played. From our perspective, we're very happy with what we see."

Consider All-Star Weekend, during which there was more hype for the 3-point contest than the dunk competition. And in the star-studded exhibition game played for millions of dopamine-craving fans, a record-breaking 48 3-pointers were made, eclipsing the previous record set just last year by 18.

The 3-pointer, not the dunk, won the weekend.

And in both the regular season and the playoffs, it has stolen the show.

"There's this supposed war between the purity of basketball and the 3-point line," Ainge says. "I don't think you have to sacrifice one for the other. There is no war against analytics from my perspective. There are great principles of old basketball -- movement, floor-spacing, screening to help your teammate, cutting and intelligence -- that still very much apply."

"The old-time coaches want to control everything, and the 3 just doesn't fit into that philosophy," D'Antoni says. "They'll fight it tooth and nail. And that's a hard thing to get over. It even still pertains a little bit today, but Golden State's trying to wipe that off the map.

"Even today, it's perceived as, 'Ah, just run the ball down, let the guys play, you don't really coach them, they're undisciplined.' Thank god for guys like Steve Kerr."